The Progression of Regret in Ishiguro's the Remains of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kazuo Ishiguro Among 13 Contenders for 2021 Booker Prize

12 Established 1961 Lifestyle Features Wednesday, July 28, 2021 Members of the Japanese senior cheerleading squad ‘Japan Pom Pom’ take part in a practice in Tokyo as the city hosts the Eighty-nine-year-old Fumie Takino (second right) joins members of the Japanese senior cheerleading squad “Japan Pom 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games. — AFP photos Pom”. Members of the Japanese senior cheerleading squad “Japan Pom Pom” stretch Members of the Japanese senior cheerleading squad “Japan Pom Pom”. Eighty-nine-year-old Fumie Takino (center) joins members of the Japanese senior before taking part in a practice in Tokyo. cheerleading squad “Japan Pom Pom”. heering is frowned upon at the They are currently rehearsing for Cheerleading is a fun way to stay fit Cvirus-postponed Olympics, but their 25th-anniversary show, which was for the “Japan Pom Pom” girls, who get training continues at a Tokyo postponed until next year because of together once a week for a rigorous gym for an energetic squad of cheer- the pandemic. Takino said it was once two-hour practice with almost no break. leaders whose average age is 70. To difficult to share her hobby with others, Masako Matsuoka, a 73-year-old mem- the beat of Taylor Swift’s “Shake It who didn’t see the appeal of senior ber of the squad, said the activity is her Off”, Fumie Takino, 89, twirled and cheerleading at first. “I couldn’t say I “ikigai”-Japanese for purpose in life. “It’s waved her pompoms as her fellow was doing cheerleading... I struggled a fun to do something different in your cheerleaders showed off their standing lot.” Their original sparkly costumes everyday life,” she explained. -

Literary Herald ISSN: 2454-3365 an International Refereed English E-Journal Impact Factor: 2.24 (IIJIF)

www.TLHjournal.comThe Literary Herald ISSN: 2454-3365 An International Refereed English e-Journal Impact Factor: 2.24 (IIJIF) Contemporary English Fiction and the works of Kazuo Ishiguro Bhawna Singh Research Scholar Lucknow University ABSTRACT The aim of this abstract is to study of memory in contemporary writings. Situating itself in the developing field of memory studies, this thesis is an attempt to go beyond the prolonged horizon of disturbing recollection that is commonly regarded as part of contemporary postcolonial and diasporic experience. it appears that, in the contemporary world the geographical mapping and remapping and its associated sense of dislocation and the crisis of identity have become an integral part of an everyday life of not only the post-colonial subjects, but also the post-apartheid ones. This inter-correlation between memory, identity, and displacement as an effect of colonization and migration lays conceptual background for my study of memory in the literary works of an contemporary writers, a Japanese-born British writer, Kazuo Ishiguro. This study is a scrutiny of some key issues in memory studies: the working of remembrance and forgetting, the materialization of memory, and the belongingness of material memory and personal identity. In order to restore the sense of place and identity to the displaced people, it may be necessary to critically engage in a study of embodied memory which is represented by the material place of memory - the brain and the body - and other objects of remembrance Vol. 1, Issue 4 (March 2016) Dr. Siddhartha Sharma Page 80 Editor-in-Chief www.TLHjournal.comThe Literary Herald ISSN: 2454-3365 An International Refereed English e-Journal Impact Factor: 2.24 (IIJIF) Contemporary English Fiction and the works of Kazuo Ishiguro Bhawna Singh Research Scholar Lucknow University In the eighteenth century the years after the forties observed a wonderful developing of a new literary genre. -

Midnight's Children by Salman Rushdie Discussion Questions

Midnight's Children by Salman Rushdie Discussion Questions 1. Midnight's Children is clearly a work of fiction; yet, like many modern novels, it is presented as an autobiography. How can we tell it isn't? What literary devices are employed to make its fictional status clear? And, bearing in mind the background of very real historical events, can "truth" and "fiction" always be told apart? 2. To what extent has the legacy of the British Empire, as presented in this novel, contributed to the turbulent character of Indian life? 3. Saleem sees himself and his family as a microcosm of what is happening to India. His own life seems so bound up with the fate of the country that he seems to have no existence as an individual; yet, he is a distinct person. How would you characterise Saleem as a human being, set apart from the novel's grand scheme? Does he have a personality? 4. "To understand just one life, you have to swallow the world.... do you wonder, then, that I was a heavy child?" (p. 109). Is it possible, within the limits of a novel, to "understand" a life? 5. At the very heart of Midnight's Children is an act of deception: Mary Pereira switches the birth-tags of the infants Saleem and Shiva. The ancestors of whom Saleem tells us at length are not his biological relations; and yet he continues to speak of them as his forebears. What effect does this have on you, the reader? How easy is it to absorb such a paradox? 6. -

BOOK REVIEWS Michael R. Reder, Ed. Conversations with Salman

258 BOOK REVIEWS Michael R. Reder, ed. Conversations with Salman Rushdie. Jackson: U of Mississippi P, 2000. Pp. xvi, 238. $18.00 pb. The apparently inexorable obsession of journalist and literary critic with the life of Salman Rushdie means it is easy to find studies of this prolific, larger-than-life figure. While this interview collection, part of the Literary Conversations Series, indicates that Rushdie has in fact spo• ken extensively both before, during, and after, his period in hiding, "giving over 100 interviews" (vii), it also substantiates a general aware• ness that despite Rushdie's position at the forefront of contemporary postcolonial literatures, "his writing, like the author himself, is often terribly misjudged by people who, although familiar with his name and situation, have never read a word he has written" (vii). The oppor• tunity to experience Rushdie's unedited voice, interviews re-printed in their entirety as is the series's mandate, is therefore of interest to student, academic and reader alike. Editor Michael Reder has selected twenty interviews, he claims, as the "most in-depth, literate and wide-ranging" (xii). The scope is cer• tainly broad: the interviews, arranged in strict chronological order, cover 1982-99, encompass every geography, and range from those tak• en from published studies to those conducted with the popular me• dia. There is stylistic variation: question-response format, narrative accounts, and extensive, and often poetic, prose introductions along• side traditional transcripts. However, it is a little misleading to infer that this is a collection comprised of hidden gems. There is much here that is commonly known, and interviews taken from existing books or re-published from publications such as Kunapipi and Granta are likely to be available to anybody bar the most casual of enthusiasts. -

Midnight's Children

Midnight’s Children by SALMAN RUSHDIE SYNOPSIS Born at the stroke of midnight at the exact moment of India’s independence, Saleem Sinai is a special child. However, this coincidence of birth has consequences he is not prepared for: telepathic powers connect him with 1,000 other ‘midnight’s children’ all of whom are endowed with unusual gifts. Inextricably linked to his nation, Saleem’s story is a whirlwind of disasters and triumphs that mirrors the course of modern India at its most impossible and glorious. ‘Huge, vital, engrossing... in all senses a fantastic book’ Sunday Times STARTING POINTS FOR YOUR DISCUSSION Consider the role of marriage in Midnight’s Children. Do you think marriage is portrayed as a positive institution? Do you think Midnight’s Children is a novel of big ideas? How well do you think it carries its themes? If you were to make a film of Midnight’s Children, who would you cast in the principle roles? What do you think of the novel’s ending? Do you think it is affirmative or negative? Is there anything you would change about it? What do you think of the portrayal of women in Midnight’s Children? What is the significance of smell in the novel? Midnight’s Children is narrated in the first person by Saleem, a selfconfessed ‘lover of stories’, who openly admits to getting some facts wrong. Why do you think Rushdie deliberately introduces mistakes into Saleem’s narration? How else does the author explore the theme of the nature of truth? What do you think about the relationship between Padma and Saleem? Consider the way that Padma’s voice differs from Saleem’s. -

The Political and Historical Background of Rushdie's Shame

Quest Journals Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Science Volume 7 ~ Issue 3 (2019)pp.:06-09 ISSN(Online):2321-9467 www.questjournals.org Research Paper The Political and Historical background of Rushdie’s Shame B. Praksh Babu, Dr. B. Krishnaiah Research Scholar Kakatiya UniversityWarangal Asst. Professor, Dept. of English & Coordinator, Entry into Services School of Humanities, University of Hyderabad, Hyderabad - 500 046 TELANGANA STATE, INDIA Corresponding Author: B. Praksh Babu ABSTRACT: The paper discusses the political and historical background portrayed in the novel Shame. Rushdie narrates the history of Pakistan since its partition from India in 1947 to the publication of the novel Shame in1983.Almost thirty six years of Pakistani history is clearly deployed in the novel. Rushdie beautifully knits the story of a newly born state from historical happenings and characters involved in a fictional manner with his literary genius. The style of using language and literary genres is significantly good. He beautifully depicts the contemporary political history and human drama exists in the postcolonial nations by the use of literary genres such as Magical realism, fantasy and symbolism. KEY WORDS: Political, Historical, Shame, Shamelessness, Magical Realism etc., Received 28 March, 2019; Accepted 08 April, 2019 © the Author(S) 2019. Published With Open Access At www.Questjournals.Org I. INTRODUCTION: The story line of Shame alludes to the sub-continental history of post-partition period through complex systems of trans-social connections between the individual and the recorded powers. The text focuses on three related families - the Shakils, the Hyders and the Harappas. The story opens in the fanciful town 'Q' - Quetta in Pakistan with the extraordinary birth of Omar Khayyam, the hero of the novel. -

On Rereading Kazuo Ishiguro Chris Holmes, Kelly Mee Rich

On Rereading Kazuo Ishiguro Chris Holmes, Kelly Mee Rich MFS Modern Fiction Studies, Volume 67, Number 1, Spring 2021, pp. 1-19 (Article) Published by Johns Hopkins University Press For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/786756 [ Access provided at 1 Apr 2021 01:55 GMT from Ithaca College ] Chris Holmes and Kelly Mee Rich 1 On Rereading Kazuo f Ishiguro Chris Holmes and Kelly Mee Rich To consider the career of a single author is necessarily an exercise in rereading. It means revisiting their work, certainly, but also, more carefully, studying how the impress of their authorship evolves over time, and what core elements remain that make them recognizably themselves. Of those authors writing today, Kazuo Ishiguro lends himself exceptionally well to rereading in part because his oeuvre, especially his novels, are so coherent. Featuring first-person narrators reflecting on the remains of their day, these protagonists struggle to come to terms with their participation in structures of harm, and do so with a formal complexity and tonal distance that suggests unreli- ability or a vexed relationship to their own place in the order of things. Ishiguro is also an impeccable re-reader, as the intertextuality of his prose suggests. He convincingly inhabits, as well as cleverly rewrites, existing genres such as the country house novel, the novel of manners, the English boarding school novel, the mystery novel, the bildung- sroman, science fiction, and, most recently, Arthurian fantasy. Artist, detective, pianist, clone: to read Ishiguro always entails rereading in relation to his own oeuvre, as well as to the literary canon. -

Addition to Summer Letter

May 2020 Dear Student, You are enrolled in Advanced Placement English Literature and Composition for the coming school year. Bowling Green High School has offered this course since 1983. I thought that I would tell you a little bit about the course and what will be expected of you. Please share this letter with your parents or guardians. A.P. Literature and Composition is a year-long class that is taught on a college freshman level. This means that we will read college level texts—often from college anthologies—and we will deal with other materials generally taught in college. You should be advised that some of these texts are sophisticated and contain mature themes and/or advanced levels of difficulty. In this class we will concentrate on refining reading, writing, and critical analysis skills, as well as personal reactions to literature. A.P. Literature is not a survey course or a history of literature course so instead of studying English and world literature chronologically, we will be studying a mix of classic and contemporary pieces of fiction from all eras and from diverse cultures. This gives us an opportunity to develop more than a superficial understanding of literary works and their ideas. Writing is at the heart of this A.P. course, so you will write often in journals, in both personal and researched essays, and in creative responses. You will need to revise your writing. I have found that even good students—like you—need to refine, mature, and improve their writing skills. You will have to work diligently at revising major essays. -

Recommended Reading for AP Literature & Composition

Recommended Reading for AP Literature & Composition Titles from Free Response Questions* Adapted from an original list by Norma J. Wilkerson. Works referred to on the AP Literature exams since 1971 (specific years in parentheses). A Absalom, Absalom by William Faulkner (76, 00) Adam Bede by George Eliot (06) The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain (80, 82, 85, 91, 92, 94, 95, 96, 99, 05, 06, 07, 08) The Aeneid by Virgil (06) Agnes of God by John Pielmeier (00) The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton (97, 02, 03, 08) Alias Grace by Margaret Atwood (00, 04, 08) All the King's Men by Robert Penn Warren (00, 02, 04, 07, 08) All My Sons by Arthur Miller (85, 90) All the Pretty Horses by Cormac McCarthy (95, 96, 06, 07, 08) America is in the Heart by Carlos Bulosan (95) An American Tragedy by Theodore Dreiser (81, 82, 95, 03) The American by Henry James (05, 07) Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy (80, 91, 99, 03, 04, 06, 08) Another Country by James Baldwin (95) Antigone by Sophocles (79, 80, 90, 94, 99, 03, 05) Anthony and Cleopatra by William Shakespeare (80, 91) Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz by Mordecai Richler (94) Armies of the Night by Norman Mailer (76) As I Lay Dying by William Faulkner (78, 89, 90, 94, 01, 04, 06, 07) As You Like It by William Shakespeare (92 05. 06) Atonement by Ian McEwan (07) Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man by James Weldon Johnson (02, 05) The Awakening by Kate Chopin (87, 88, 91, 92, 95, 97, 99, 02, 04, 07) B "The Bear" by William Faulkner (94, 06) Beloved by Toni Morrison (90, 99, 01, 03, 05, 07) A Bend in the River by V. -

Ruth Prawer Jhabvala's Adapted Screenplays

Absorbing the Worlds of Others: Ruth Prawer Jhabvala’s Adapted Screenplays By Laura Fryer Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of a PhD degree at De Montfort University, Leicester. Funded by Midlands 3 Cities and the Arts and Humanities Research Council. June 2020 i Abstract Despite being a prolific and well-decorated adapter and screenwriter, the screenplays of Ruth Prawer Jhabvala are largely overlooked in adaptation studies. This is likely, in part, because her life and career are characterised by the paradox of being an outsider on the inside: whether that be as a European writing in and about India, as a novelist in film or as a woman in industry. The aims of this thesis are threefold: to explore the reasons behind her neglect in criticism, to uncover her contributions to the film adaptations she worked on and to draw together the fields of screenwriting and adaptation studies. Surveying both existing academic studies in film history, screenwriting and adaptation in Chapter 1 -- as well as publicity materials in Chapter 2 -- reveals that screenwriting in general is on the periphery of considerations of film authorship. In Chapter 2, I employ Sandra Gilbert’s and Susan Gubar’s notions of ‘the madwoman in the attic’ and ‘the angel in the house’ to portrayals of screenwriters, arguing that Jhabvala purposely cultivates an impression of herself as the latter -- a submissive screenwriter, of no threat to patriarchal or directorial power -- to protect herself from any negative attention as the former. However, the archival materials examined in Chapter 3 which include screenplay drafts, reveal her to have made significant contributions to problem-solving, characterisation and tone. -

The Self-Contradictory Narrative of Mr Stevens

The Self-Contradictory Narrative of Mr Stevens In Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day Kenny Johansson EN1C02 Literary Essay Department of Languages and Literatures University of Gothenburg June 2011 Supervisor: Ann Katrin Jonsson Examiner: Celia Aijmer-Rydsjö 2 Table of Contents 1. Introduction 3 2. Mr Stevens 6 3. Miss Kenton 11 4. Lord Darlington 16 5. Conclusion 21 Works Cited 22 3 1. Introduction Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day is a tale about the English butler Mr Stevens, who during the prime of his life served Lord Darlington, a man labelled as a traitor to his country following the Second World War. Provided with his new employer’s Ford and a couple of days off from his work at Darlington Hall, Stevens starts a motoring trip around the English countryside. The purpose of the journey is to convince his previous co-worker Miss Kenton, and as shall be discussed in the course of this essay also the object of Stevens’ affections, to return to Darlington Hall. However, the places he visits and the people he encounters cause Stevens to begin to dwell on his past at Darlington Hall, which has been his only world for the largest part of his life. The story is told from a first person point of view, narrated by Stevens in the form of a diary in which he interweaves his recollections from the glory days of Darlington Hall in the 1920s and 1930s with his current thoughts and speculations on various encounters during his motoring trip in 1956. -

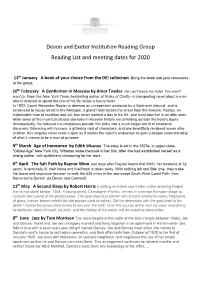

DEI Reading List 2020

Devon and Exeter Institution Reading Group Reading List and meeting dates for 2020 13th January A book of your choice from the DEI collection. Bring the book and your comments to the group. 10th February A Gentleman in Moscow by Amor Towles He can't leave his hotel. You won't want to. From the New York Times bestselling author of Rules of Civility--a transporting novel about a man who is ordered to spend the rest of his life inside a luxury hotel. In 1922, Count Alexander Rostov is deemed an unrepentant aristocrat by a Bolshevik tribunal, and is sentenced to house arrest in the Metropol, a grand hotel across the street from the Kremlin. Rostov, an indomitable man of erudition and wit, has never worked a day in his life, and must now live in an attic room while some of the most tumultuous decades in Russian history are unfolding outside the hotel's doors. Unexpectedly, his reduced circumstances provide him entry into a much larger world of emotional discovery. Brimming with humour, a glittering cast of characters, and one beautifully rendered scene after another, this singular novel casts a spell as it relates the count's endeavour to gain a deeper understanding of what it means to be a man of purpose 9th March Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton The story is set in the 1870s, in upper-class, "Gilded-Age" New York City. Wharton wrote the book in her 50s, after she had established herself as a strong author, with publishers clamouring for her work.