CS2016 Mpub.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lived Experience of Military Brats of Color In

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: THERE IS NO PLACE LIKE HOME: THE LIVED EXPERIENCE OF MILITARY BRATS OF COLOR IN COLLEGE Alicia Marie Peralta, Doctor of Philosophy, 2019 Dissertation directed by: Professor Francine H. Hultgren Department of Teaching and Learning, Policy and Leadership Military children of color live in various cultural contexts, often outside of mainstream U.S. society, leading to questions about their experiences as young people of color in college settings. To this end, this dissertation asks: What is the lived experience of military brats of color in college? This dissertation explores the experiences of seven military children of color in college settings as they navigate leaving their unique military context, encounter identities they did not know they had, and individuate from their families and the military context. The phenomenological questioning of identity coupled with conceptions of home and belonging shine a light on the bittersweet experience of the military brats of color feeling like strangers in their own country. These experiences are uncovered using Gadamerian (1975/2004) horizons and Heidegger’s dasein (1927/2008b) in addition to O’Donohue’s (1997, 1998) philosophical writings on belonging and home. The thematizing process brought forth experiences of attempting to forge an identity in the midst of preconceived ideas about who and what you should be as a person. The process of forging identity includes the transition from the military community to college; a settling into college; and a choosing of identity. Pedagogical insights include a critique of identity and how it is constructed, specifically because military children of color are never of a place, but move with and in spaces. -

Living with Stories

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2008 Living With Stories William Schneider Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the Indigenous Studies Commons Recommended Citation Schneider, W. S., & Crowell, A. (2008). Living with stories: Telling, re-telling, and remembering. Logan: Utah State University Press. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Living with Stories Telling, Re-telling, and Remembering Living with Stories Telling, Re-telling, and Remembering Edited by William Schneider With Essays by Aron L. Crowell and Estelle Oozevaseuk Holly Cusack-McVeigh Sherna Berger Gluck Lorraine McConaghy Joanne B. Mulcahy Kirin Narayan Utah State University Press Logan, Utah Copyright © 2008 Utah State University Press All rights reserved Utah State University Press Logan, Utah 84322–7800 www.usu.edu/usupress Manufactured in the United States of America Printed on acid-free, recycled paper ISBN 978–0–87421–689-9 (cloth) ISBN 978–0–87421–690-5 (e-book) Chapter 3 was fi rst published as Aron L. Crowell and Estelle Oozevaseuk. 2006. “The St. Lawrence Island Famine and Epidemic, 1878–1880: A Yupik Narrative in Cultural and Historical Perspective.” Arctic Anthropology 43(1):1–19. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Living with stories : telling, re-telling, and remembering / edited by William Sch- neider ; with essays by Aron L. Crowell ... [et al]. -

Papau New Guinea, Soloman Islands, and Vanuatu

PAPUA NEW GUINEA COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS Mary Seymour Olmsted 1975-1979 Ambassador, Papua New Guinea Harvey Feldman 1979-1981 Ambassador, Papua New Guinea Morton R. Dworken, Jr. 1983-1985 Deputy Chief of Mission, Port Moresby Paul F. Gardner 1984-1986 Ambassador, Papua New Guinea Robert Pringle 1985-1987 Deputy Chief of Mission, Port Moresby Everett E. Bierman 1986-1989 Ambassador, Papua New Guinea William Farrand 1990-1993 Ambassador, Papua New Guinea Richard W. Teare 1993-1996 Ambassador, Papua New Guinea John Allen Cushing 1997-1998 Consular/Political Officer, Port Moresby Arma Jane Karaer 1997-2000 Ambassador, Papua New Guinea MARY SEYMOUR OLMSTED Ambassador Papua New Guinea (1975-1979) Ambassador Mary Seymour Olmsted was born in Duluth, Minnesota and raised in Florida. She received a bachelor's degree in economics from Mount Holyoke College and a master's degree from Columbia University. Ambassador Olmsted's Foreign Service career included positions in India, Iceland, Austria, Washington, DC, and an ambassadorship to Papua New Guinea. Ambassador Olmsted was interviewed by Charles Stuart Kennedy in 1992. Q: That's an awful lot of responsibility, I would think. Now you went out to Port Moresby. That was in June of '74? OLMSTED: Yes. Q: As principal officer. So in other words, you were made Consul General. Sworn in and so forth. 1 OLMSTED: Yes. Q: At that time, did you know that was going to become an Embassy? OLMSTED: It seemed quite likely. Papua New Guinea, in the beginning, was obviously on the road to independence, and no one knew exactly when it would take place. -

October 1999

,. "You don't just need a computer, you need a solution." Fmal Cut Pro ~= Ultura digital video camcorder canon studied your life, your needs and all 27 bones in your hand. Also available, with many of the fine features of the Ultura: Ultura Features: z_~ Genuine canon Optics 16X Opticai/320X Digital zoom Lens Canon Minii)."T Optical Image Stabilization Mini~" (Canon original technology) Canon Flexizone Auto Focus/Auto Exposure (Canon exclusive) on/y$999 2.5" Color LCD View screen & Color Viewfinder PCM Digital Stereo sound Program Auto Exposure Digital Photo Mode alpha tech COMPUTERS.COM (360) 671-2334 • (800) 438-3216 • (360) 671-8571 Fax 2300 James Street, Bellingham, WA 98225 • www.alphatechcomputers.com Hewlett-Packard Apple Solutions We are fully AdvanceNet certified to maintain, We are fully Apple®certified to maintain, alpha tech computers is a place of solutions service and repair all ~ service and repair all Apple® products. for you, no matter what computer equipment Hewlett-Packard products. l...=:J • . Apple Specialist you hove, or, where you bought it . LOCAL SPOTLIGHT ............................ 5 LOCAL SHOWS ................................ 6-7 LOCAL RECORDINGS ................ 8-1 0 ALL AGE VENUES ................ 12-1 5 MAN ... OR ASTROMAN ? .... 16-18 BILL FRISELL ....................... :20-21 FOLKANDWORLD BEAT .................. 23 THEATER REVIEWS ................................ 24 MOVIE REVIEWS ...................................... 25 DINNER WITH HAMILTON ................ 26 P. IN THE SQUARED CIRCLE .......... 27 -

L'italia E L'eurovision Song Contest Un Rinnovato

La musica unisce l'Europa… e non solo C'è chi la definisce "La Champions League" della musica e in fondo non sbaglia. L'Eurovision è una grande festa, ma soprattutto è un concorso in cui i Paesi d'Europa si sfidano a colpi di note. Tecnicamente, è un concorso fra televisioni, visto che ad organizzarlo è l'EBU (European Broadcasting Union), l'ente che riunisce le tv pubbliche d'Europa e del bacino del Mediterraneo. Noi italiani l'abbiamo a lungo chiamato Eurofestival, i francesi sciovinisti lo chiamano Concours Eurovision de la Chanson, l'abbreviazione per tutti è Eurovision. Oggi più che mai una rassegna globale, che vede protagonisti nel 2016 43 paesi: 42 aderenti all'ente organizzatore più l'Australia, che dell'EBU è solo membro associato, essendo fuori dall'area (l’anno scorso fu invitata dall’EBU per festeggiare i 60 anni del concorso per via dei grandi ascolti che la rassegna fa in quel paese e che quest’anno è stata nuovamente invitata dall’organizzazione). L'ideatore della rassegna fu un italiano: Sergio Pugliese, nel 1956 direttore della RAI, che ispirandosi a Sanremo volle creare una rassegna musicale europea. La propose a Marcel Bezençon, il franco-svizzero allora direttore generale del neonato consorzio eurovisione, che mise il sigillo sull'idea: ecco così nascere un concorso di musica con lo scopo nobile di promuovere la collaborazione e l'amicizia tra i popoli europei, la ricostituzione di un continente dilaniato dalla guerra attraverso lo spettacolo e la tv. E oltre a questo, molto più prosaicamente, anche sperimentare una diretta in simultanea in più Paesi e promuovere il mezzo televisivo nel vecchio continente. -

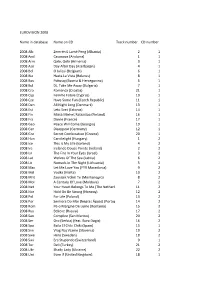

EUROVISION 2008 Name in Database Name on CD Track Number CD

EUROVISION 2008 Name in database Name on CD Track number CD number 2008 Alb Zemrën E Lamë Peng (Albania) 2 1 2008 And Casanova (Andorra) 1 1 2008 Arm Qele, Qele (Armenia) 3 1 2008 Aze Day After Day (Azerbaijan) 4 1 2008 Bel O Julissi (Belgium) 6 1 2008 Bie Hasta La Vista (Belarus) 8 1 2008 Bos Pokusaj (Bosnia & Herzegovina) 5 1 2008 Bul DJ, Take Me Away (Bulgaria) 7 1 2008 Cro Romanca (Croatia) 21 1 2008 Cyp Femme Fatale (Cyprus) 10 1 2008 Cze Have Some Fun (Czech Republic) 11 1 2008 Den All Night Long (Denmark) 13 1 2008 Est Leto Svet (Estonia) 14 1 2008 Fin Missä Miehet Ratsastaa (Finland) 16 1 2008 Fra Divine (France) 17 1 2008 Geo Peace Will Come (Georgia) 19 1 2008 Ger Disappear (Germany) 12 1 2008 Gre Secret Combination (Greece) 20 1 2008 Hun Candlelight (Hungary) 1 2 2008 Ice This Is My Life (Iceland) 4 2 2008 Ire Irelande Douze Pointe (Ireland) 2 2 2008 Isr The Fire In Your Eyes (Israel) 3 2 2008 Lat Wolves Of The Sea (Latvia) 6 2 2008 Lit Nomads In The Night (Lithuania) 5 2 2008 Mac Let Me Love You (FYR Macedonia) 9 2 2008 Mal Vodka (Malta) 10 2 2008 Mnt Zauvijek Volim Te (Montenegro) 8 2 2008 Mol A Century Of Love (Moldova) 7 2 2008 Net Your Heart Belongs To Me (The Netherlands) 11 2 2008 Nor Hold On Be Strong (Norway) 12 2 2008 Pol For Life (Poland) 13 2 2008 Por Senhora Do Mar (Negras Águas) (Portugal) 14 2 2008 Rom Pe-o Margine De Lume (Romania) 15 2 2008 Rus Believe (Russia) 17 2 2008 San Complice (San Marino) 20 2 2008 Ser Oro (Serbia) (feat. -

MA Thesis: Linguistics: English Language and Linguistics

MA thesis: Linguistics: English Language and Linguistics Sean de Goede S0871346 First reader: Tony Foster Second reader: Lettie Dorst Leiden University Faculty of Humanities Department of Linguistics 08-06-2015 Language Switches in Eurovision Song Contest Lyrics 1 The Stylistics of Language Switches in Lyrics of Entries of the Eurovision Song Contest MA thesis: Linguistics: English Language and Linguistics Sean de Goede S0871346 First reader: Tony Foster Second reader: Lettie Dorst Leiden University Faculty of Humanities Department of Linguistics 08-06-2015 Language Switches in Eurovision Song Contest Lyrics 2 Acknowledgements It did not come as a surprise to the people around me when I told them that the subject for my Master’s thesis was going to be based on the Eurovision Song Contest. Ever since I was a little boy I have been a fan, and some might even say that I became somewhat obsessed, for which I cannot really blame them. Moreover, I have always had a special interest in mixed language songs, so linking the two subjects seemed only natural. Thanks to a rather unfortunate turn of events, this thesis took a lot longer to write than was initially planned, but nevertheless, here it is. Special thanks are in order for my supervisor, Tony Foster, who has helped me in many ways during this time. I would also like to thank a number of other people for various reasons. The second reader Lettie Dorst. My mother, for being the reason I got involved with the Eurovision Song Contest. My father, for putting up with my seemingly endless collection of Eurovision MP3s in the car. -

Cj E&M (130960.Kq)

CJ E&M (130960.KQ) Top player in Korea’s media content market Company Report │ Sep 21, 2017 As Korea’s leading media content company, CJ E&M’s efforts to improve its content competitiveness over the past few years have finally begun to bear fruit. Also positive, we point out that the firm has a wide variety of anticipated content lined up for the peak season of 4Q. Meanwhile, thanks to Buy (initiate) the strong success of music group Wanna One, we expect CJ E&M’s music business to continue showing strong growth. Reflecting these positives, we TP W100,000 ( initiate ) predict that CJ E&M’s share price will rise going forward. CP (’17/09/19) W79,500 Sector Media Kospi/Kosdaq 2,416.05 / 674.48 Market cap (common) US$2,729.8mn Outstanding shares (common) 38.7mn Stands as Korea’s number-one media content platform 52W high (’17/01/20) W88,700 CJ E&M is Korea’s number-one content producer/platform operator. Positive low (’16/12/05) W53,800 Average trading value (60D) US$12.1mn results from its investment in content over the past few years are to start being Dividend yield (2017E) 0.25% reflected in the firm’s earnings from 2017, and should continue to boost its Foreign ownership 28.3% earnings figures in 2018. Major shareholders CJ Corp and 5 others 42.9% 1) Media content division: Operating throughout the industry value chain (via its Wellington Management Hong Kong Limited and one other 5.1% broadcasting platforms, drama production and writing arms), the media Share perf 3M 6M 12M content division boasts strong competitiveness. -

Literary Fiction KOLBRUN THORA EIRIKSDOTTIR [email protected]

Please note that a fund for the promotion of Icelandic literature operates under the auspices of the Icelandic Ministry Forlagid of Education and Culture and subsidizes translations of literature. Rights For further information please write to: Icelandic Literature Center Hverfisgata 54 | 101 Reykjavik Agency Iceland Phone +354 552 8500 [email protected] | www.islit.is BACKLIST literary fiction KOLBRUN THORA EIRIKSDOTTIR [email protected] VALGERDUR BENEDIKTSDOTTIR [email protected] literary fiction rights-agency Andri Snaer Magnason Kristin Helga Gunnarsdottir Alfrun Gunnlaugsdottir Kristin Marja Baldursdottir Ari Johannesson Kristin Steinsdottir Armann Jakobsson Ofeigur Sigurdsson Arni Thorarinsson Olafur Gunnarsson Audur Jonsdottir Oskar Magnusson Bjorg Magnusdottir Dagur Hjartarson Petur Gunnarsson Einar Karason Ragna Sigurdardottir Einar Mar Gudmundsson Sigurbjorg Thrastardottir Eirikur Orn Norddahl Sigurdur Palsson Elisabet Jokulsdottir Sjón Frida A. Sigurdardottir Solveig Jonsdottir Gerdur Kristny Steinunn G. Helgadottir Gudbergur Bergsson Steinunn Johannesdottir Gudmundur Oskarsson Gudmundur Andri Thorsson Svava Jakobsdottir Gudrun fra Lundi Sverrir Norland Halldor Laxness Solvi Bjorn Sigurdsson Haukur Ingvarsson Thorbergur Thordarson Hjörtur Marteinsson Thor Vilhjalmsson Indridi G. Thorsteinsson Thorarinn Eldjarn Jakobina Sigurdardottir Thorarinn Leifsson Jon Atli Jonasson Thorunn Valdimarsdottir Jon Gnarr Jonina Leosdottir Tryggvi Emilsson Kari Tulinius Valur Gunnarsson Kristin Eiriksdottir Vilborg Davidsdottir └ Index LITERARY FICTION ANDRI SNAER MAGNASON (b.1973) has won the Icelandic Literary Prize for both fiction, children’s book and non-fiction. His work has been published or performed in over thirty countries and has received numerous international awards, amongst them the Janusz Korczak Honorary Award, the French Grand Prix de l’Imaginire and the Kairos prize awarded by the Alfred To- epfer Foundation to outstanding individuals. Magnason has been active in the fight against the destruction of the Icelan- dic Highlands. -

AFP-Volume-2-Issue-1.Pdf

Archives of Forensic Psychology c 2014 Global Institute of Forensic Psychology 2014, Vol. 1, No. 1, 1–13 ISSN 2334-2749 Crime on the Border: Use of Evidence in Customs Interviews P¨arAnders Granhag Department of Psychology, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden Norwegian Police University College, Oslo, Norway Department of Psychology, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway Franziska Clemens Department of Psychology, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden Leif A. Str¨omwall Department of Psychology, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden Erik Mac Giolla∗ Department of Psychology, University of Gothenburg, Box 500, 405 30 Gothenburg, Sweden, [email protected] Customs officers are an understudied population in psycho-legal research. The present study is an attempt to fill this gap by examining customs officers’ interview strategies. Specifically, in an experimental setup, we examined how customs officers (N = 80) planned to use evidence in an investigative interview. Half the customs officers were members of a crime-fighting unit (less experienced interviewers) and half were members of an investigative unit (more experienced interviewers). Participants were randomly assigned to two evidence conditions: weak or strong. Participants extracted evidence from a mock crime brief and described how they would use this evidence in a suspect interview. Of the extracted pieces of evidence only 15% were planned to be used in a strategic manner. Evidence strength did not influence whether participants planned to use evidence strategically. The results showed that members of the crime-fighting unit were less likely to use evidence strategically than members of the investigative unit. Completed training courses were associated with an improvement in the planned use of evidence. -

Name Artist Composer Album Grouping Genre Size Time Disc

Name Artist Composer Album Grouping Genre Size Time Disc Number Disc Count Track Number Track Count Year Date Mod ified Date Added Bit Rate Sample Rate Volume Adjustment Kind Equalizer Comments Plays Last Played Skips Last Ski pped My Rating Because The Beatles Abbey Road Pop 4149082 165 1969 02.07.2011 13:37 02.07.2011 13:31 192 44100 MPEG audio file , AG# DF7AFDAC Carry That Weight The Beatles Abbey Road Pop 2501496 96 1969 02.07.2011 13:37 02.07.2011 13:31 192 44100 MPEG audio file , AG# 74 DF4189 Come Together The Beatles Abbey Road Pop 6431772 260 1969 02.07.2011 13:37 02.07.20 11 13:31 192 44100 MPEG audio file , AG# 5081C2D4 The End The Beatles Abbey Road Pop 3532174 139 1969 02.07.2011 13:37 02.07.2011 13:31 192 44100 MPEG audio file , AG# 909B4CD9 Golden Slumbers The Beatles Abbey Road Pop 2374226 91 1969 02.07.2011 13:37 02.07.20 11 13:31 192 44100 MPEG audio file , AG# D91DAA47 Her Majesty The Beatles Abbey Road Pop 731642 23 1969 02.07.2011 13:37 02.07.20 11 13:31 192 44100 MPEG audio file , AG# 8427BD1F 1 02.07.2011 13:33 Here Comes The Sun The Beatles Abbey Road Pop 4629955 185 1969 02.07.2011 13:37 02.07.2011 13:31 192 44100 MPEG audio file , AG# 23 6DC926 3 30.10.2011 18:20 4 02.07.2011 13:34 I Want You The Beatles Abbey Road Pop 11388347 467 1969 02.07.2011 13:38 02.07.20 11 13:31 192 44100 MPEG audio file , AG# 97501696 Maxwell's Silver Hammer The Beatles Abbey Road Pop 5150946 207 1969 02.07.2011 13:38 02.07.2011 13:31 192 44100 MPEG audio file , AG# 78 0B3499 Mean Mr Mustard The Beatles Abbey Road Pop 1767349 66 1969 -

SCHINDLER's LIST Screenplay by Steven Zaillian Based on the Novel

SCHINDLER'S LIST Screenplay by Steven Zaillian Based on the novel by Thomas Keneally USE FOR EDUCATIONAL PURPOSES ONLY IN BLACK AND WHITE: EXT. RURAL POLAND - SMALL DEPOT - DAY A small depot set down against monotonous countryside in the far hinterlands of rural Poland. A folding table on the wood- plank platform. Pens, ink well, forms. A three year old girl holding the hand of woman watches a clerk register her name and those of two or three families of farmers standing before him. Finishing, he motions to an SS guard nearby to escort them to a waiting, empty, idling passenger train. The people climb aboard as the clerk gathers his paperwork. He folds up his little table, signals with a wave to the engineer, and climbs up after them. The nearly-empty train pulls out of the sleepy station. EXT. TRAIN STATION, CRACOW, POLAND - DAY TRAIN WHEELS grinding against track, slowing. FOLDING TABLE LEGS scissoring open. The lever of a train door being pulled. NAMES ON LISTS on clipboards held by an ARMY OF CLERKS moving alongside the tracks. CLERKS (O.S.) ... Rossen ... Lieberman ... Wachsberg ... Groder ... HUNDREDS OF BEWILDERED RURAL FACES coming down off the train. FORMS being set out on the folding tables. HANDS straightening pens and pencils and ink pads and stamps. CLERKS (O.S.) ... when your name is called, go over there... take this over to that table... TYPEWRITER KEYS rapping a name onto a list. A FACE. Keys typing another NAME. Another FACE. CLERKS (V.O.) ... you're in the wrong line, wait over there..