Thesis Muchenje F.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

March Newsletter 2016 .Pdf

Email : [email protected] Goldridge College Website: www.goldridgecollege.ac.zw Facebook Page : www.facebook.com/ GoldridgeCollegeKwekweZimbabwe Twitter: @GoldridgeCol Monthly Newsletter Fax : 055 – 21353 Phone : 055 – 21363 March 2016 Cell : 0782081881 This issue Dear Parents IMPORTANT DATES FOR TERM TWO The end of the short first term is upon us. We give glory to CAMBRIDGE INTERNATIONAL the Almighty God for all our achievements and protection EXAMINATIONS LEARNER AWARDS FOR as we traversed the country. We greatly appreciate all 2015 your support throughout the term. I hope you will enjoy NATIONAL ALLIED ARTS MUSICAL having your children home with you. As for us, we already COMPETITIONS look forward to an exciting and enjoyable term two. SPORTS CRICKET IMPORTANT DATES ATHLETICS They say “Every end is a new beginning” and herewith the TERM TWO SPORTS important dates for term two to enable you to plan SDC FUNDRAISING ACTIVITIES accordingly. HOLIDAY OFFICE HOURS Event Date The office will be open during school School Opens Tuesday, 3 May holidays as follows: First Fixture Free Weekend Saturday, 21 to Sunday, 22 May Thursday, 24 March 2016 8.00 a.m. to 1.00 p.m. Exeat Friday, 17 to Monday 20 June Tuesday, 29 March to Friday, 1 April Second Fixture Free Weekend Saturday, 16 to Sunday, 17 July 8.00 a.m. to 1.00 p.m. School Closes Thursday, 4 August Monday, 25 to Friday, 29 April 8.00 a.m. to 1.00 p.m. Monday, 2 May onwards – normal working hours. CAMBRIDGE INTERNATIONAL EXAMINATIONS LEARNER AWARDS FOR 2015 While the first term was successful in many regards, the Cambridge Outstanding Learner Awards for 2015 were an icing on the cake. -

Nuzn 1 9 9 0

7 Q 4 U: Workers 7 Q 4 U: Workers Rights to be Sustained AI JG 2 91!990 LO- Intifada ie peak of olifical awareness LIvLAEJ on r1 A Suppliers of Comet Trucks, and Service Parts Leyland (Zimbabwe) Limited Watts Road Southerton Phone: 67861 /,- T :M4-2G ZW CONTENTS E d ito ria l ................................................. .......................................... ........................ 2 Letters ............................................................................. 3 President Opens First Session of the Third Parliament o f Z im b a b w e ............................................................................................................... 6 President Mugabe Addresses May Day ....................... 11 Worker's Position Needs More Improvements .......................... 13 Ministry to Redress Shortage of Neurologists ............................ 15 Magadu Re-elected to Lead Urban Councils .............................. 16 Msika Calls for Collective Efforts in Industrialisation and Employment Creation ................... 18 Government to Establish Ventures Capital Company - C h id z e ro .............................................................................................................. 2 1 Existing Telephone Services Must be U se d R e sp o n sib ly ...................................... .................... ............................... 2 2 Street Vagrants on Increase - A Concern .............................23 ZA NU PF Launches W eekly ................................................................... -

Saints' Weekly

AMDG SAINTS’ WEEKLY SPORTS AND CULTURE Vol. 20 Issue 03 31 January 2020 Edited by Mr. A H Macdonald BASKETBALL vs Eaglesvale CROSS COUNTRY U14A Won 17-4 U16A Won 19-14 School Name Points Position U14B Lost 2-10 2nd team Won 25-17 Prince Edward School 177 1 U15A Won 15-14 1st team Won 79-36 U15B Lost 6-7 Peterhouse Boys 231 2 1st team Watershed College 479 3 Lomagundi College 519 4 On Friday, the basketball first team, The Wolves, hosted an unpredictable Eaglesvale side as they continued to prepare for an Wise Owl School 534 5 explosive derby against rivals St John's College on February 7th. Gateway High School 570 6 The Wolves quickly came out of the blocks to lead by 11 points after St Georges College 610 7 the first quarter. The throwers, as Eaglesvale are affectionately known, managed to reduce the deficit in the second quarter to head into the Milestone College 814 8 half time trailing by a respectable margin. USAP 1006 9 St George's came out guns blazing in the second half, displaying a fiery character typical of Saints teams, to annihilate Eaglesvale and win by a huge margin. Despite a great all round team performance, the WATERPOLO – Arthur Gower Memorial Trophy highlights of the game were two 3-pointers in quick succession by C Timveos, and a breath-taking dunk from Captain M Musariri which sent 1st team Vs Hellenic Lost 1-8 the crowd into a frenzy. The win complimented a good day out on the Vs Falcon Lost 1-8 court for all Saints basketball teams. -

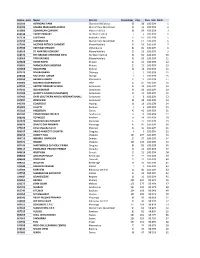

Zimbabwegrade7passrates A4

Centre_num Name District _Candidates Pass_ Pass_rate Rank 015100 ASPINDALE PARK Glenview Mufakose 38 38 100.00% 1 015785 DIVARIS MAKAHARIS JUNIOR Warren Park Mabelreign 16 16 100.00% 2 015800 DOMINICAN CONVENT Mbare Hatfield 69 69 100.00% 3 016130 HAPPY PRIMARY Northern Central 9 9 100.00% 4 017120 LUSITANIA Mabvuku Tafara 51 51 100.00% 5 017250 MARANATHA Warren Park Mabelreign 61 61 100.00% 6 017390 MOTHER PATRICK CONVENT Mbare Hatfield 53 53 100.00% 7 017590 PATHWAY PRIVATE Chitungwiza 60 60 100.00% 8 018160 ST. MARTINS CONVENT Mbare Hatfield 35 35 100.00% 9 018470 THE GRANGE CHRISTIAN SCHO Northern Central 50 50 100.00% 10 018560 TWO BRIGADE Mbare Hatfield 69 69 100.00% 11 025828 CROSS KOPJE Mutare 21 21 100.00% 12 026692 MANICALAND CHRISTIAN Mutare 15 15 100.00% 13 027008 MILESTONE Makoni 18 18 100.00% 14 027575 MVURACHENA Chipinge 5 5 100.00% 15 028400 MUTARAZI JUNIOR Nyanga 6 6 100.00% 16 035050 BARNIES JUNIOR Marondera 11 11 100.00% 17 035060 BEATRICE GOVERNMENT Seke 47 47 100.00% 18 035722 DESTINY PRIMARY SCHOOL Goromonzi 14 14 100.00% 19 037242 OLD WINDSOR Goromonzi 94 94 100.00% 20 037308 QUALITY JUNIOR (RUVHENEKO) Goromonzi 19 19 100.00% 21 037482 SAISS (SOUTHERN AFRICA INTERNATIONAL) Goromonzi 8 8 100.00% 22 037897 WINDVIEW Goromonzi 38 38 100.00% 23 045300 COALFIELDS Hwange 18 18 100.00% 24 055002 ALLETTA Kwekwe 6 6 100.00% 25 055010 ANDERSON Gweru 42 42 100.00% 26 057432 PAMAVAMBO PRIVATE Zvishavane 13 13 100.00% 27 058030 TORWOOD Kwekwe 54 54 100.00% 28 067670 NGOMAHURU PRIMARY Masvingo 27 27 100.00% 29 068870 ZIMUTO ZRP -

PROVISIONAL VOTERS' ROLL INSPECTION CENTRES Ser Province District Constituency Local Authority Ward Polling Station Name Registrants No

PROVISIONAL VOTERS' ROLL INSPECTION CENTRES Ser Province District Constituency Local Authority Ward Polling Station Name Registrants No. of Stations BULAWAYO METROPOLITAN PROVINCE 1 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 1 City Hall 1608 2 2 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 1 Eveline High School 561 1 3 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 1 Mckeurtan Primary School 184 1 4 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 1 Milton Junior School 294 1 5 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 1 Old Bulawayo Polytechnic 259 1 6 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 1 Peter Pan Nursery School 319 1 7 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 1 Pick and Pay Tent 473 1 8 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 1 Robert Tredgold Primary School 211 1 9 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 2 Airport Primary School 261 1 10 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 2 Aiselby Primary School 118 1 11 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 2 Baines Infants School 435 1 12 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 2 Baines Junior School 1256 2 13 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 2 Falls Garage Tent 273 1 14 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo -

Mipf Suspended Pensioners October 2017

MIPF SUSPENDED PENSIONERS OCTOBER 2017 The following are names of MIPF pensioners whose benefits have been suspended for various reasons and whose whereabouts are not known. If anyone has information about their whereabouts or those of their close relatives, kindly advise MIPF. NAME OF PENSIONER LAST MINE WORKED FORLAST KNOWN ADDRESS AARON PHIRI,JULIO WAITI GATHS C/O C G MPOFU MONTFORT PRESS/PP P O BOX 5592 LIMBE MALAWI ERENIMO AARON ARCTURUS CHINGOMBE LEA SCHOOL P O BOX 5 MWANZA MALAWI SOMBA ABSI RAN MINE MATENGANYO VILLAGE P O BOX 276 MANGOCHI MALAWI ABASI MADI ZIMASCO C/O NDANDALA T P T P O BOX 43 NAMWERA MANGOCHI MALAWI ABUDU KAZEMBE VENICE VENICE MINE P BAG 741 KADOMA SIBANDA GIBBON NICHOLISON HSE NO 26K PO BOX 29 COLLEN BAWN CHISARE ADAM NGAWI MWALALA SHACKLETON CHAKAKA F P SCHOOL P BAG 2 BENGA NKHOTA KOTA MALAWI ADAMU ISAAC GOLDEN VALLEY HOLD MAIL BRODERICK ROSEMARY DIANA (MRS) MHANGURA P O BOX 761 MALELANE 1320 R S A BRODERICK ROSEMARY DIANA (MRS) MHANGURA HOLD MAIL ADILIYASI SILIYA CAESAR HOLD MAIL ADINI ALLIE JENA HOLD MAIL ADINI MINO ARCTURUS HOLD MAIL ANDREA FOINA MHANGURA MAZAMBARA PRIMARY SCHOOL P BAG 144 MUSHUMBI FANI SHAMISO HWANGE COLLIERY MAKOVERE PRIMARY SCHOOL P O BOX 1 ZVISHAVANE MKWANDA AJIBU LYSON VENICE CHISINA SECONDARY SCHOOL P O BOX 217 GOKWE AJIDA SANUDI TIGER REEF 11 GREY ST GLEN WOOD KWE KWE SINGINI AKIM,KABAYA ALASKA BANDA F P SCHOOL V/H MUNDAGO N/A MWAS P/A USISYA NKATA BAY MALAWI MAZUKE (ZHAMAROMBE)ALBERT SHABANIE BELLA SCHOOL P BAG 523 CHIVI CHICHORO BERNARD RIO TINTO CHEGUTU T/SHIP HOUSE NO 24046 CHEGUTU -

ICDL, As the Basic Digital

BEST PRACTICE AWARDS www.ecdl.org 2014 CONTENTS CORPORATE/PRIVATE CENTRAL ASIA - COURSEWARE AND TRAINING OF TRAINERS – SUSTAINABLE APPROACH TO THE PROMOTION OF ICDL 2 IRAN - ICDL COURSES FOR THE PERSONNEL OF PARSIAN HOTELS CORPORATION 4 KENYA - KK TRAINING 6 ZIMBABWE - ICDL FOR MIDLANDS CHRISTIAN COLLEGE STUDENTS AND STAFF 8 GOVERNMENT/PUBLIC AFGHANISTAN - CAPACITY BUILDING FOR FUTURE TEACHERS IN AFGHANISTAN 12 EGYPT - ARAB ACADEMY FOR SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY & MARITIME TRANSPORT 15 IRAN - PUBLIC SCHOOLS IN AARAN & BIDGOL TOWN AND RURAL AREAS OF KASHAN TOWN 17 ITALY - THE ITALIAN EXCELLENCE: BOCCONI UNIVERSITY 20 LIBYA - ICDL FOR THE UNEMPLOYED IN LIBYA 23 NIGERIA - E-TECH/FRSC ICDL CERTIFICATION FOR FIELD OFFICERS AND MANAGEMENT STAFF 25 ROMANIA - COMPUTER KNOWLEDGE AND MEDICAL INFORMATICS FOR DEVELOPING THE NURSES’ ADAPTABILITY IN THE HOSPITALS IN ROMANIA 27 SINGAPORE - ICDL ENABLES WOMEN BACK TO THE WORKFORCE 29 SOCIAL INCLUSION AUSTRIA - SPORT WITH PROSPECTS 32 COLOMBIA - STRATEGIC ALLIANCE FOR COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT IN AREAS OF RISK DUE TO ARMED CONFLICT, LLANOS REGION, COLOMBIA 35 GREECE - GETBUSY.GR 38 ICDL GCC - PROMOTING THE ICDL BRAND THROUGH CSR CONTRIBUTION: MAKING SURE OUR CHILDREN ARE SAFE IS OUR TOP PRIORITY 40 IRAN - ICDL KNOWLEDGE AND SKILLS, A SOLUTION FOR EMPOWERING THE INDIVIDUALS 43 ROMANIA - ICT TRAINING AT EUROPEAN STANDARDS IN ROMANIAN PRISONS 46 SINGAPORE - ENABLING PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES IN SINGAPORE THROUGH ICDL CURRICULUM 48 SOUTH AFRICA (1) - THE PAPILLON FOUNDATION - CREATING BETTER TOMORROWS…FROM THE ASHES -

Parliamentary Elections 2005 Polling Stations

PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS 2005 POLLING STATIONS MASHONALAND WEST PROVINCE As published in The Zimbabwe Independent dated March 18, 2005 Polling stations shall be open from 0700 hours to 1900 hours on polling day HURUNGWE EAST CONSTITUENCY No Polling station Presiding Officer 1 Bakwa Primary School 2 Broadacres Farm 3 Chibara Primary School 4 Chiedza Shopping Ctr 5 Chikangwe Primary School 6 Chikora Primary School 7 Chikuti Primary School 8 Chikuti Angwa Bridge 9 Chiango Primary School 10 Chipapa Resettlement Scheme 11 Chitenje Primary School 12 Chitikira Primary School 13 Demavend Farm 14 Dentrow Primary School 15 Desist Primary School 16 Dete Primary School 17 Dixie Primary School 18 Dunga Primary School 19 Garahanga Primary School 20 Garika Primary School 21 Goodhope Primary School 22 Helwyn Primary School 23 Hesketh Park Primary School 24 Hilltop Resetlement Scheme 25 Ian Penny Farm 26 Jambo Farm 27 Jenya Farm 28 Kachiva Primary School 29 Kangeire Farm 30 Kapiri Primary School 31 Karoi Junior School 32 Karoin Enterprises Primary School 33 Kasimure Primary School 34 Kazangarare Primary School 35 Ketsanga Primary School 36 Lancaster Primary School 37 Lanroy Primary School 38 Lazy Five Primary School 39 Leconfields Farm 40 Lynx Mine Primary School 41 Madzimoyo Primary School 42 Mahuti Primary School 43 Makwiye Primary School 44 Masokoti Primary School 45 Mashongwe Primary School 46 Maunga Farm 47 Mauya Primary School 48 Marshlands Farm 49 Masikati Farm 50 Mlichi Primary School 51 Moy Farm 52 Mpofu River Primary School 53 Mshowe Primary School -

2Nd Term Calendar 2017.Pdf

HILLCREST SCHOOLS SECOND TERM CALENDAR 2017 HILLCREST COLLEGE E-mails: Accounts: [email protected] Head: [email protected] HILLCREST SCHOOLS Administrator: [email protected] Bursar: [email protected] School Office: [email protected] or [email protected] Facebook: hillcrestcollegeZW Website: www.hillcrestcollege.net Important Numbers Sports Director: +263 (0)772 100 780 Hostel Superintendent: +263 (0)772 249 003 The Head Schools Administrator: +263 (0)772 270 289 Hillcrest Preparatory School Bursar: +263 (0)772 100 748 Mr. J. Mutangadura Deputy Headmaster: +263 (0)772 137 036 [email protected] Head: +263 (0)772 249 007 The Head HILLCREST PREPARATORY SCHOOL Hillcrest College Emails: Mrs. A. Holman School Office: [email protected] [email protected] Important Numbers Head: +263 (0) 772 100 746 Deputy Head: +263 (0) 772 137 038 Secretary: +263 (0) 772 249 009 School Landline: +263 (0)20 63120 Laverock House: +263 (0)20 66747 +263 (0) 779 595 361 NB: The calendar is subject to change GENERAL INFORMATION HILLCREST COLLEGE (HC) Mondays 09 50 Divisional Head’s/House Assembly Tuesday 09 50 Chapel Service TERM DATES 2017 Wednesdays 09 50 Head’s Assembly Thursdays 09 50 Tutor Period/Hymn Singing Fridays 09 50 Sports Assembly Term 1 Starts: Tuesday 10 January Divisional Head’s Assembly Venues Ends: Thursday 6 April Form 1 Rugby Shade 1 Form 2 Rugby Shade 3 Term 2 Form 3 Rugby Shade 4 Form 4 Beit Hall Starts: Tuesday 9 May Lower 6 Library Ends: Thursday 10 August Upper 6 Study Hall Term 3 House Assembly Venues Starts: Tuesday 12 September Bvumba Rugby Shades Ends: Thursday 7 December Chimanimani Lecture Theatre Nyangani Beit Hall HILLCREST PREPARATORY SCHOOL (HPS) Mondays 09 30 Head’s Assembly Thursdays 09 30 Hymn Singing WEEK 1 WEEK 14 Mon. -

PROVISIONAL VOTERS' ROLL INSPECTION CENTRES Ser Province District Constituency Local Authority Ward Polling Station Name Registrants No

PROVISIONAL VOTERS' ROLL INSPECTION CENTRES Ser Province District Constituency Local Authority Ward Polling Station Name Registrants No. of Stations BULAWAYO METROPOLITAN PROVINCE 1 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 1 City Hall 1608 2 2 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 1 Eveline High School 561 1 3 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 1 Mckeurtan Primary School 184 1 4 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 1 Milton Junior School 294 1 5 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 1 Old Bulawayo Polytechnic 259 1 6 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 1 Peter Pan Nursery School 319 1 7 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 1 Pick and Pay Tent 473 1 8 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 1 Robert Tredgold Primary School 211 1 9 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 2 Airport Primary School 261 1 10 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 2 Aiselby Primary School 118 1 11 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 2 Baines Infants School 435 1 12 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 2 Baines Junior School 1256 2 13 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 2 Falls Garage Tent 273 1 14 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo -

MIPF SUSPENDED PENSIONERS AS at 30 SEPTEMBER 2016 The

MIPF SUSPENDED PENSIONERS AS AT 30 SEPTEMBER 2016 The following are names of MIPF pensioners whose benefits have been suspended for various reasons and whose whereabouts are not known. If anyone has information about their whereabouts or those of their close relatives, kindly advise MIPF. NAME OF PENSIONER LAST MINE WORKED FOR LAST KNOWN ADDRESS AARON PHIRI,JULIO WAITI GATHS C/O C G MPOFU MONTFORT PRESS/PP P O BOX 5592 LIMBE MALAWI ABASI MADI ZIMASCO C/O NDANDALA T P T P O BOX 43 NAMWERA MANGOCHI MALAWI ABREHU ALFREDO DYOPO REDBUCK HOLD ABUDU KAZEMBE VENICE VENICE MINE P BAG 741 KADOMA ADAMA KANGOMA RAN MINE HOLD MAIL ADAMU ISAAC GOLDEN VALLEY HOLD MAIL ADILIYASI SILIYA CAESAR HOLD MAIL ADINI ALLIE JENA MINE HOLD MAIL ADINI CHINGANDA RENCO C/O TANDIWE REST HOUSE P O BOX 4 MAKANJIRA MALAWI ADINI JOHN HOWMINE STAND NO 74 OWNERSHIP SITE TSANZAGURU RUSAPE ADINI MINO ARCTURUS HOLD MAIL AFIKI ALFRED WANKIE C/O COMMERCIAL BANK OF MALAWI MANGOCHI BRANCH P O BOX 106 MANGOCHI MALAWI AFIKI KACHULU EMPRESS LIWO ESTATE P O BOX 448 MANGOCHI MALAWI AJIDA SANUDI TIGER REEF 11 GREY ST GLEN WOOD KWE KWE AKIMU JAFALI PATCHWAY CHILAMBULA VILLAGE T/A NDINDI P O NGODZI SALIMA MALAWI AKIMU MWACHUMU KAZEMBE HOW MINE ANDIAMO TECHNOLICAL POLE P O BOX 44 BALAKA MALAWI ALBERTO NICHODIMU MADZIWA HOLD MAIL ALI ,CHIPONGOZI MHANGURA P BAG 7703 HOUSE NO S 40 LIONS DEN CHINHOYI ALI ACHUWALIRA PETRO RHODESIAN CHROME MACHENGA FP SCHOOL P O BOX 85 BALAKA MALAWI ALIDI KASSIM UNKI TIGER REEF MINE P O BOX 713 KWEKWE ALIKANJELI LEONARD CAESAR BENNETT ENTERPRISES P O BOX 140 CONCESSION -

Saints' Weekly

AMDG SAINTS’ WEEKLY SPORTS AND CULTURE Compiled by St George’s students Vol. 20 Issue 05 14 February 2020 Edited by Mr. A H Macdonald CRICKET vs LOMAGUNDI COLLEGE BASKETBALL 1st XI (T/20 match) – Friday 7th February vs St John’s College St George’s 99-9 Lomagundi 100-4 (Dan Myers 2-23) U14A Won 8-2 U16A Lost 21-25 Results: - Lost by 6 wickets U14B Lost 6-10 U16B Lost 10-11 th U14C Won 8-2 U16C Won 7-0 Saturday 8 February U15A Lost 13-23 2nd team Lost 14-21 st All matches rain affected and reduced to 25 overs. U15B Lost 8-14 1 team Lost 62-87 U15C Won 5-4 1st XI U14 vs St John’s College St George’s 195-5 (E Bawa 79. M Gwese 62) Lomagundi 94-3 (T Chisango 2-30. E Bawa 2-11. T Manyeza 2-3) A team - It was a very tough game but the boys showed their true colours and Results: - won by 101 runs managed to win the game 12-2. We had 4 points from E Chivasa and M Mungwadzi and 2 points from A Tamangani and A Chingwecha. U16A St George’s 127 all out (A Chifamba 31) By A Tamangani and E Chivasa. Lomagundi 128-9 (A Chipunza 3-20. M Chimhini 2-22) Results: - lost by 1 wicket B team - The game was hard but as the boys showed great determination. We knew we should win. St John’s tried to make a comeback but soon all hope was U15A lost as they were slowly losing with the final score as 10-6 in our favour.