Introduction an AACM BOOK: ORIGINS, ANTECEDENTS, OBJECTIVES, METHODS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joseph Jarman's Black Case Volume I & II: Return

Joseph Jarman’s Black Case Volume I & II: Return From Exile February 13, 2020 By Cam Scott When composer, priest, poet, and instrumentalist Joseph Jarman passed away in January 2019, a bell sounded in the hearts of thousands of listeners. As an early member of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM), as well as its flagship group, the Art Ensemble of Chicago, Jarman was a key figure in the articulation of Great Black Music as a multi- generational ethic rather than a standard repertoire. As an ordained Buddhist priest, Jarman’s solicitude transcended philosophical affinity and deepened throughout his life as his music evolved. His musical, poetic, and religious paths appear to have been mutually informative, in spite of a hiatus from public performance in the nineties—and to encounter Jarman’s own words is to understand as much. The full breadth of this complexity is celebrated in the long-awaited reissue of Black Case Volume I & II: Return from Exile, a blend of smut and sutra, poetry and polemic, that feels like a reaffirmation of Jarman’s ambitious vision in the present day. Black Case wears its context proudly. A near-facsimile of the original 1977 publication by the Art Ensemble of Chicago (which itself was built upon a coil-bound printing from 1974), the volume serves as a time capsule of a key period in the development of an emancipatory musical and cultural program, and an intimate portrait of the artist-as-revolutionary. Black Case, then, feels most contemporary where it is most of its time, as a document of Black militancy and programmatic self-determination in which—to paraphrase Larry Neal’s 1968 summary of the Black Arts Movement—ethics and aesthetics, individual and community, are tightly unified. -

Dave Burrell, Pianist Composer Arranger Recordings As Leader from 1966 to Present Compiled by Monika Larsson

Dave Burrell, Pianist Composer Arranger Recordings as Leader From 1966 to present Compiled by Monika Larsson. All Rights Reserved (2017) Please Note: Duplication of this document is not permitted without authorization. HIGH Dave Burrell, leader, piano Norris Jones, bass Bobby Kapp, drums, side 1 and 2: b Sunny Murray, drums, side 2: a Pharoah Sanders, tambourine, side . Recording dates: February 6, 1968 and September 6, 1968, New York City, New York. Produced By: Alan Douglas. Douglas, USA #SD798, 1968-LP Side 1:West Side Story (L. Bernstein) 19:35 Side 2: a. East Side Colors (D. Burrell) 15:15 b. Margy Pargy (D. Burrell 2:58 HIGH TWO Dave Burrell, leader, arranger, piano Norris Jones, bass Sunny Murray, drums, side 1 Bobby Kapp, drums side 2. Recording Dates: February 6 and September 9, 1968, New York City, New York. Produced By: Alan Douglas. Additional production: Michael Cuscuna. Trio Freedom, Japan #PA6077 1969-LP. Side: 1: East Side Colors (D. Burrell) 15:15 Side: 2: Theme Stream Medley (D.Burrell) 15:23 a.Dave Blue b.Bittersweet Reminiscence c.Bobby and Si d.Margie Pargie (A.M. Rag) e.Oozi Oozi f.Inside Ouch Re-issues: High Two - Freedom, Japan TKCB-70327 CD Lions Abroad - Black Lion, UK Vol. 2: Piano Trios. # BLCD 7621-2 2-1996CD HIGH WON HIGH TWO Dave Burrell, leader, arranger, piano Sirone (Norris Jones) bass Bobby Kapp, drums, side 1, 2 and 4 Sunny Murray, drums, side 3 Pharoah Sanders, tambourine, side 1, 2, 4. Recording dates: February 6, 1968 and September 6, 1968, New York City, New York. -

Gagosian Gallery

artnet June 28, 2019 GAGOSIAN ‘It’s True Musical Abstraction’: Artist Theaster Gates on His Plan to Break New Barriers in Sound Art at the Park Avenue Armory The artist will lead his Black Artists Retreat at the Park Avenue Armory's Drill Hall in October. Taylor Dafoe Theaster Gates introduces Discussions of the Sonic Imagination, Part II, 2019, at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden. Photo by Shannon Finney. This time last year, the Park Avenue Armory’s Drill Hall, one of the largest columnless spaces in New York City, desperately needed a new floor. Many of the 138-year-old wooden boards were cracked or crumbling; the support structure underneath was deteriorating. So the non-profit body in charge of the space, the Park Avenue Armory Conservancy, secured $4 million in funds (half of which came from the city) to rebuild it. That’s when Theaster Gates stepped in. He was already in talks with the Armory to do an ambitious project there this year, so he offered to source and mill some of the rare, recycled Georgia yellow pine for the reconstruction through his urban renewal project in Chicago, the Rebuild Foundation. Now, over the course of a weekend this October, Gates will get to see the foundation’s efforts in action when he mounts the newest iteration of his Black Artists Retreat at the Drill Hall. A protean gathering of black artists, academics, curators, and other creators, the retreat was founded by Gates and fellow Chicago-based artist Eliza Myrie, and held annually in their hometown between 2013 and 2016. -

Surrealism-Revolution Against Whiteness

summer 1998 number 9 $5 TREASON TO WHITENESS IS LOYALTY TO HUMANITY Race Traitor Treason to whiteness is loyaltyto humanity NUMBER 9 f SUMMER 1998 editors: John Garvey, Beth Henson, Noel lgnatiev, Adam Sabra contributing editors: Abdul Alkalimat. John Bracey, Kingsley Clarke, Sewlyn Cudjoe, Lorenzo Komboa Ervin.James W. Fraser, Carolyn Karcher, Robin D. G. Kelley, Louis Kushnick , Kathryne V. Lindberg, Kimathi Mohammed, Theresa Perry. Eugene F. Rivers Ill, Phil Rubio, Vron Ware Race Traitor is published by The New Abolitionists, Inc. post office box 603, Cambridge MA 02140-0005. Single copies are $5 ($6 postpaid), subscriptions (four issues) are $20 individual, $40 institutions. Bulk rates available. Website: http://www. postfun. com/racetraitor. Midwest readers can contact RT at (312) 794-2954. For 1nformat1on about the contents and ava1lab1l1ty of back issues & to learn about the New Abol1t1onist Society v1s1t our web page: www.postfun.com/racetraitor PostF un is a full service web design studio offering complete web development and internet marketing. Contact us today for more information or visit our web site: www.postfun.com/services. Post Office Box 1666, Hollywood CA 90078-1666 Email: [email protected] RACE TRAITOR I SURREALIST ISSUE Guest Editor: Franklin Rosemont FEATURES The Chicago Surrealist Group: Introduction ....................................... 3 Surrealists on Whiteness, from 1925 to the Present .............................. 5 Franklin Rosemont: Surrealism-Revolution Against Whiteness ............ 19 J. Allen Fees: Burning the Days ......................................................3 0 Dave Roediger: Plotting Against Eurocentrism ....................................32 Pierre Mabille: The Marvelous-Basis of a Free Society ...................... .40 Philip Lamantia: The Days Fall Asleep with Riddles ........................... .41 The Surrealist Group of Madrid: Beyond Anti-Racism ...................... -

Fall 2015 Uchicago Arts Guide

UCHICAGO ARTS FALL 2015 EVENT & EXHIBITION HIGHLIGHTS IN THIS ISSUE The Renaissance Society Centennial UChicago in the Chicago Architecture Biennial CinéVardaExpo.Agnès Varda in Chicago arts.uchicago.edu BerlinFullPage.pdf 1 8/21/15 12:27 PM 2015 Randy L. and Melvin R. BERLIN FAMILY LECTURES CONTENTS 5 Exhibitions & Visual Arts 42 Youth & Family 12 Five Things You (Probably) Didn’t 44 Arts Map Know About the Renaissance Society 46 Info 17 Film 20 CinéVardaExpo.Agnès Varda in Chicago 23 Design & Architecture Icon Key 25 Literature Chicago Architecture Biennial event 28 Multidisciplinary CinéVardaExpo event C M 31 Music UChicago 125th Anniversary event Y 39 Theater, Dance & Performance UChicago student event CM MY AMITAV GHOSH The University of Chicago is a destination where ON THE COVER CY artists, scholars, students, and audiences converge Daniel Buren, Intersecting Axes: A Work In Situ, installation view, CMY T G D and create. Explore our theaters, performance The Renaissance Society, Apr 10–May 4, 1983 K spaces, museums and galleries, academic | arts.uchicago.edu F, H, P A programs, cultural initiatives, and more. Photo credits: (page 5) Attributed to Wassily Kandinsky, Composition, 1914, oil on canvas, Smart Museum of Art, the University of Chicago, Gift of Dolores and Donn Shapiro in honor of Jory Shapiro, 2012.51.; Jessica Stockholder, detail of Rose’s Inclination, 2015, site-specific installation commissioned by the Smart Museum of Art;page ( 6) William G W Butler Yeats (1865–1939), Poems, London: published by T. Fisher Unwin; Boston: Copeland and Day, 1895, promised Gift of Deborah Wachs Barnes, Sharon Wachs Hirsch, Judith Pieprz, and Joel Wachs, AB’92; Justin Kern, Harper Memorial Reading Room, 2015, photo courtesy the artist; page( 7) Gate of Xerxes, Guardian Man-Bulls of the eastern doorway, from Erich F. -

Randy Brecker Randypop! Pete Mccann Range Nicole Mitchell

ment that he can go deep in any setting, wheth- er it’s the bristling, harmonically challenging opener “Kenny” (his ode to the late trumpet- er/%ugelhornist Kenny Wheeler), the angu- lar, odd-metered “Seventh Jar,” the urgent- ly swinging “Realm” (dedicated to pianist Richie Beirach), the Frisellian heartland bal- lad “To "e Mountains” or the pedal-to-the- metal fusion anthem “Mustard.” "ere’s even a 12-tone-in%uenced piece in the darkly disso- nant “Numinous.” Hey is the invaluable utility in!elder here, acquitting himself brilliantly on acoustic piano (“Kenny,” “Realm,” “Seventh Jar”), Fender Randy Brecker Pete McCann Rhodes electric piano (“Dyad Changes,” Range “Rumble,” “Bridge Scandal”) and organ RandyPOP! WHIRLWIND 4675 (“Mustard”). Saxophonist O’Gallagher, who PILOO RECORDS 009 ++++½ plays cascading unison lines alongside McCann +++½ A remarkable post-Pat Metheny contemporary on several of the intricate heads here, also deliv- ers outstanding solos on the uptempo swingers jazz guitarist, Pete McCann has %own some- With his younger brother Michael, trumpeter “Dyad Changes” and “Realm” and on the rau- what under the radar since the ’90s, though Randy Brecker helped de!ne the sound of early cous “Bridge Scandal.” It’s a formidable, %exi- the quality of his playing and depth of his writ- jazz-rock in out!ts like Dreams and the Brecker ing ranks alongside his generational colleagues ble out!t with a built-in chemistry and an auda- Brothers Band while also accruing an impres- Ben Monder and Kurt Rosenwinkel. He stakes cious streak. —Bill Milkowski sive “straight” jazz resume with everyone out highly original territory on his !$h out- from Horace Silver and Art Blakey to Charles ing as a leader in the company of pianist-key- Range: Kenny; Seventh Jar; Realm; To The Mountains: Mustard; Dyad Changes; Numinous; Bridge Scandal; Rumble; Mine Is Yours. -

Musicnow CONCLUDES 2014/15 SERIES with PROGRAM FEATURING WORK by AVANT-GARDE JAZZ ARTISTS JOHN ZORN and MYRA MELFORD

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Press Contacts: May 21, 2015 Eileen Chambers, 312.294.3092 Rachelle Roe, 312.294.3090 Photos Available By Request [email protected] MusicNOW CONCLUDES 2014/15 SERIES WITH PROGRAM FEATURING WORK BY AVANT-GARDE JAZZ ARTISTS JOHN ZORN AND MYRA MELFORD Program Also Includes Works by Esa-Pekka Salonen and Chicago-based Composer Marc Mellits June 1 Concert Marks Final MusicNOW Program Curated by CSO’s Mead Composers-in-Residence Mason Bates and Anna Clyne Monday, June 1 at 7 p.m. at Harris Theater CHICAGO — The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s (CSO) acclaimed MusicNOW series— dedicated to showcasing contemporary music through an innovative concert experience— concludes its 2014/15 season Monday, June 1, at 7 p.m. in a program led by MusicNOW principal conductor Cliff Colnot at the Harris Theater for Music and Dance in Millennium Park (205 E. Randolph Dr., Chicago). The June 1 concert marks the final MusicNOW program curated by the CSO’s Mead Composers-In-Residence Mason Bates and Anna Clyne, who have guided the vision and development for the concert series since their appointment by CSO Zell Music Director Riccardo Muti in 2010. The June 1 MusicNOW program is performed by musicians of the CSO and special guest musicians including composer, pianist and Chicago-area native Myra Melford. It features two works by Guggenheim Fellow Melford, as well as works by American avant-garde composer John Zorn, internationally-acclaimed composer/conductor Esa-Pekka Salonen and American composer Marc Mellits. The concert experience is enhanced by special visual elements created by the Chicago-based film making collective Cinema Libertad, as well as DJ sets from illmeasures before and after the concert. -

Thumbscrew-Never Is Enough PR

Bio information: THUMBSCREW Title: NEVER IS ENOUGH (Cuneiform Rune 478) Format: CD / VINYL (DOUBLE) / DIGITAL www.cuneiformrecords.com FILE UNDER: JAZZ How much is too much when it comes to THUMBSCREW? The All-Star Collective Trio Delivers a Decisive Answer with Their Sixth Album NEVER IS ENOUGH a Riveting Program of Originals by Tomas Fujiwara, Mary Halvorson and Michael Formanek A funny thing happened while Thumbscrew was hunkered down at City of Asylum, the Pittsburgh arts organization that has served as a creative hotbed for the collective trio via a series of residencies. Late in the summer of 2019 the immediate plan was for drummer Tomas Fujiwara, guitarist Mary Halvorson and bassist Michael Formanek to rehearse and record a disparate program of Anthony Braxton compositions they’d gleaned from his Tri-Centric Foundation archives, pieces released last year on The Anthony Braxton Project, a Cuneiform album celebrating his 75th birthday. At the same time, the triumvirate brought in a batch of original compositions that they also spent time refining and recording, resulting in Never Is Enough, a brilliant program of originals slated for release on Cuneiform. There’s a precedent for twined projects by the trio serving as fascinating foils for each other. In June 2018, Cuneiform simultaneously released an album of Thumbscrew originals, Ours, and Theirs, a disparate but cohesive session exploring music by the likes of Brazilian choro master Jacob do Bandolim, pianist Herbie Nichols, and Argentine tango master Julio de Caro. Those albums were also honed and recorded during a City of Asylum residency. While not intended as the same kind of dialogue, The Anthony Braxton Project and Never Is Enough do seem to speak eloquently (if cryptically) to each other. -

The Amazing Tomeka Reid

Newsletter of the New Directions Cello Association & Festival Inc. Vol 23, No. 2, Winter, 2017 Welcome to the Nexus of the Next Step in Cello! In this issue: * Message from the Director * New Directions 2017! June 16-18, Ithaca, NY * Interview: The amazing Tomeka Reid * New Directions 2016: A Look Back * Cd Review: Bryan Wilson’s Oso Perezoso * The CelLowdown: Final Words Message from the Director By Chris White Greetings! We have an incredibly exciting festival planned for this summer at Ithaca College, June 16-18. The guest artists for this, our 23rd annual festival, will be Yaniel Matos (São Paulo, Brazil), Tomeka Reid with Artifacts Trio (Chicago), Malcolm Parson (New Orleans), Gunther Tiedemann (Cologne, Germany), Zach Brown & Friends (NYC) and Jake Charkey (Mumbai, India). Please check out our new website at http:// newdirectionscello.org/ to read about these amazing players from around the country and the world. We hope that you can join us for this special long weekend in beautiful Ithaca, New York, in the heart of the Finger Lakes region of Central New York state. As is no doubt obvious by now, we will not be holding our 2017 New Directions Cello Festival in Germany as we’d originally hoped. However, we are currently working on New Directions in Germany for 2018 – possibly in July. In addition to Cello City Online, you can keep up on the latest Chris White, Founder & Artistic Director New Directions Cello news and videos on our Facebook page. New Directions Cello Association and Festival Remember: we’re a 501c3 organization, the only one in the world dedicated exclusively to promoting non-classical uses 123 Rachel Carson Way of the cello. -

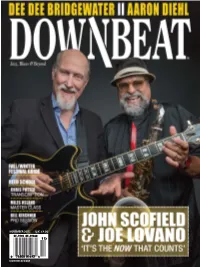

Downbeat.Com November 2015 U.K. £4.00

NOVEMBER 2015 2015 NOVEMBER U.K. £4.00 DOWNBEAT.COM DOWNBEAT JOHN SCOFIELD « DEE DEE BRIDGEWATER « AARON DIEHL « ERIK FRIEDLANDER « FALL/WINTER FESTIVAL GUIDE NOVEMBER 2015 NOVEMBER 2015 VOLUME 82 / NUMBER 11 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer ĺDQHWDÎXQWRY£ Circulation Manager Kevin R. Maher Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes Bookkeeper Emeritus Margaret Stevens Editorial Assistant Stephen Hall Editorial Intern Baxter Barrowcliff ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Sam Horn 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; -

Sustaining Afrocentric Spiritual Jazz in 21St Century Chicago

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2016 Sacred Freedom: Sustaining Afrocentric Spiritual Jazz in 21St Century Chicago Adam Zanolini The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1617 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] SACRED FREEDOM: SUSTAINING AFROCENTRIC SPIRITUAL JAZZ IN 21ST CENTURY CHICAGO by ADAM ZANOLINI A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2016 © 2016 ADAM ZANOLINI All Rights Reserved ii Sacred Freedom: Sustaining Afrocentric Spiritual Jazz in 21st Century Chicago by Adam Zanolini This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Music in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _________________ __________________________________________ DATE David Grubbs Chair of Examining Committee _________________ __________________________________________ DATE Norman Carey Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: _________________ __________________________________________ DATE Jeffrey Taylor _________________ __________________________________________ DATE Fred Moten _________________ __________________________________________ DATE Michele Wallace iii ABSTRACT Sacred Freedom: Sustaining Afrocentric Spiritual Jazz in 21st Century Chicago by Adam Zanolini Advisor: Jeffrey Taylor This dissertation explores the historical and ideological headwaters of a certain form of Great Black Music that I call Afrocentric spiritual jazz in Chicago. However, that label is quickly expended as the work begins by examining the resistance of these Black musicians to any label. -

Make It New: Reshaping Jazz in the 21St Century

Make It New RESHAPING JAZZ IN THE 21ST CENTURY Bill Beuttler Copyright © 2019 by Bill Beuttler Lever Press (leverpress.org) is a publisher of pathbreaking scholarship. Supported by a consortium of liberal arts institutions focused on, and renowned for, excellence in both research and teaching, our press is grounded on three essential commitments: to be a digitally native press, to be a peer- reviewed, open access press that charges no fees to either authors or their institutions, and to be a press aligned with the ethos and mission of liberal arts colleges. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, California, 94042, USA. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.11469938 Print ISBN: 978-1-64315-005- 5 Open access ISBN: 978-1-64315-006- 2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019944840 Published in the United States of America by Lever Press, in partnership with Amherst College Press and Michigan Publishing Contents Member Institution Acknowledgments xi Introduction 1 1. Jason Moran 21 2. Vijay Iyer 53 3. Rudresh Mahanthappa 93 4. The Bad Plus 117 5. Miguel Zenón 155 6. Anat Cohen 181 7. Robert Glasper 203 8. Esperanza Spalding 231 Epilogue 259 Interview Sources 271 Notes 277 Acknowledgments 291 Member Institution Acknowledgments Lever Press is a joint venture. This work was made possible by the generous sup- port of