Human Use of Restored and Naturalized Delta Landscapes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

0 5 10 15 20 Miles Μ and Statewide Resources Office

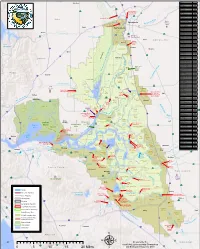

Woodland RD Name RD Number Atlas Tract 2126 5 !"#$ Bacon Island 2028 !"#$80 Bethel Island BIMID Bishop Tract 2042 16 ·|}þ Bixler Tract 2121 Lovdal Boggs Tract 0404 ·|}þ113 District Sacramento River at I Street Bridge Bouldin Island 0756 80 Gaging Station )*+,- Brack Tract 2033 Bradford Island 2059 ·|}þ160 Brannan-Andrus BALMD Lovdal 50 Byron Tract 0800 Sacramento Weir District ¤£ r Cache Haas Area 2098 Y o l o ive Canal Ranch 2086 R Mather Can-Can/Greenhead 2139 Sacramento ican mer Air Force Chadbourne 2034 A Base Coney Island 2117 Port of Dead Horse Island 2111 Sacramento ¤£50 Davis !"#$80 Denverton Slough 2134 West Sacramento Drexler Tract Drexler Dutch Slough 2137 West Egbert Tract 0536 Winters Sacramento Ehrheardt Club 0813 Putah Creek ·|}þ160 ·|}þ16 Empire Tract 2029 ·|}þ84 Fabian Tract 0773 Sacramento Fay Island 2113 ·|}þ128 South Fork Putah Creek Executive Airport Frost Lake 2129 haven s Lake Green d n Glanville 1002 a l r Florin e h Glide District 0765 t S a c r a m e n t o e N Glide EBMUD Grand Island 0003 District Pocket Freeport Grizzly West 2136 Lake Intake Hastings Tract 2060 l Holland Tract 2025 Berryessa e n Holt Station 2116 n Freeport 505 h Honker Bay 2130 %&'( a g strict Elk Grove u Lisbon Di Hotchkiss Tract 0799 h lo S C Jersey Island 0830 Babe l Dixon p s i Kasson District 2085 s h a King Island 2044 S p Libby Mcneil 0369 y r !"#$5 ·|}þ99 B e !"#$80 t Liberty Island 2093 o l a Lisbon District 0307 o Clarksburg Y W l a Little Egbert Tract 2084 S o l a n o n p a r C Little Holland Tract 2120 e in e a e M Little Mandeville -

MARSH LANDING GENERATING STATION Contra Costa County, California Application for Certi

Responses to Data Request Set 2: (#60–63) ApplicationApplication for for Certification Certification (08-AFC-03)(08-AFC-03) forfor MARSHMARSH LANDING LANDING GENERATINGGENERATING STATION STATION ContraContra Costa Costa County, County, California California June 2009 Prepared for: Prepared by: Marsh Landing Generating Station (08-AFC-3) Responses to CEC Data Requests 60 through 63 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS RESPONSES TO DATA REQUESTS 60 THROUGH 63 BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES 60 THROUGH 63 TABLES Table 63-1 Cumulative Sources for Marsh Landing Generating Station and Willow Pass Generating Station Table 63-2 AERMOD Cumulative Impact Modeling Results FIGURES Figure 60-1 Inorganic Nitrogen Wet Deposition from Nitrate and Ammonium, 2007 Figure 62-1a Nitrogen Deposition Isopleth Map - Vegetation Figure 62-1b Nitrogen Deposition Isopleth Map - Wildlife Figure 63-1a Cumulative Sources Nitrogen Deposition Isopleths - Vegetation Figure 63-1b Cumulative Sources Nitrogen Deposition Isopleths - Wildlife i Marsh Landing Generating Station (08-AFC-3) Responses to CEC Data Requests 60 through 63 Table of Contents LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS USED IN RESPONSES AAQS ambient air quality standard AERMOD American Meteorological Society and Environmental Protection Agency preferred atmospheric dispersion model BAAQMD Bay Area Air Quality Management District CCPP Contra Costa Power Plant CEC California Energy Commission CEMS continuous emissions monitoring system cm/sec centimeters per second CO carbon monoxide K Kelvin kg/ha/yr kilograms per hectare -

Transitions for the Delta Economy

Transitions for the Delta Economy January 2012 Josué Medellín-Azuara, Ellen Hanak, Richard Howitt, and Jay Lund with research support from Molly Ferrell, Katherine Kramer, Michelle Lent, Davin Reed, and Elizabeth Stryjewski Supported with funding from the Watershed Sciences Center, University of California, Davis Summary The Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta consists of some 737,000 acres of low-lying lands and channels at the confluence of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers (Figure S1). This region lies at the very heart of California’s water policy debates, transporting vast flows of water from northern and eastern California to farming and population centers in the western and southern parts of the state. This critical water supply system is threatened by the likelihood that a large earthquake or other natural disaster could inflict catastrophic damage on its fragile levees, sending salt water toward the pumps at its southern edge. In another area of concern, water exports are currently under restriction while regulators and the courts seek to improve conditions for imperiled native fish. Leading policy proposals to address these issues include improvements in land and water management to benefit native species, and the development of a “dual conveyance” system for water exports, in which a new seismically resistant canal or tunnel would convey a portion of water supplies under or around the Delta instead of through the Delta’s channels. This focus on the Delta has caused considerable concern within the Delta itself, where residents and local governments have worried that changes in water supply and environmental management could harm the region’s economy and residents. -

Methyl and Total Mercury Spatial and Temporal Trends in Surficial Sediments of the San Francisco Bay-Delta

Methyl and Total Mercury Spatial and Temporal Trends in Surficial Sediments of the San Francisco Bay-Delta Assessment of Ecological and Human Health Impacts of Mercury in the Bay-Delta Watershed CALFED Bay-Delta Mercury Project Final Report Submitted to: Mark Stephenson California Department of Fish and Game Moss Landing Marine Labs 7544 Sandholdt Road Moss Landing, CA 95039 Submitted by: Wesley A. Heim Moss Landing Marine Laboratories 8272 Moss Landing Rd Moss Landing, CA 95039 [email protected] (email) 831-771-4459 (voice) Dr. Kenneth Coale Moss Landing Marine Laboratories 8272 Moss Landing Rd Moss Landing, CA 95039 Mark Stephenson California Department of Fish and Game Moss Landing Marine Labs 7544 Sandholdt Road Moss Landing, CA 95039 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Recent studies indicate significant amounts of mercury are transported into the Bay-Delta from the Coastal and Sierra mountain ranges. In response to mercury contamination of the Bay-Delta and potential risks to humans, health advisories have been posted in the estuary, recommending no consumption of large striped bass and limited consumption of other sport fish. The major objective of the CALFED Bay-Delta Mercury Project “Assessment of Ecological and Human Health Impacts of Mercury in the Bay-Delta Watershed” is to reduce mercury levels in fish tissue to levels that do not pose a health threat to humans or wildlife. This report summarizes the accomplishments of the Moss Landing Marine Laboratories (MLML) and California Department of Fish and Game (CDF&G) at Moss Landing as participants in the CALFED Bay-Delta Mercury Project. Specific objectives of MLML and CDF&G include: 1. -

GRA 9 – South Delta

2-900 .! 2-905 .! 2-950 .! 2-952 2-908 .! .! 2-910 .! 2-960 .! 2-915 .! 2-963 .! 2-964 2-965 .! .! 2-917 .! 2-970 2-920 ! .! . 2-922 .! 2-924 .! 2-974 .! San Joaquin County 2-980 2-929 .! .! 2-927 .! .! 2-925 2-932 2-940 Contra Costa .! .! County .! 2-930 2-935 .! Alameda 2-934 County ! . Sources: Esri, DeLorme, NAVTEQ, USGS, Intermap, iPC, NRCAN, Esri Japan, METI, Esri China (Hong Kong), Esri (Thailand), TomTom, 2013 Calif. Dept. of Fish and Wildlife Area Map Office of Spill Prevention and Response I Data Source: O SPR NAD_1983_C alifornia_Teale_Albers ACP2 - GRA9 Requestor: ACP Coordinator Author: J. Muskat Date Created: 5/2 Environmental Sensitive Sites Section 9849 – GRA 9 South Delta Table of Contents GRA 9 Map ............................................................................................................................... 1 Table of Contents ...................................................................................................................... 2 Site Index/Response Action ...................................................................................................... 3 Summary of Response Resources for GRA 9......................................................................... 4 9849.1 Environmentally Sensitive Sites 2-900-A Old River Mouth at San Joaquin River....................................................... 1 2-905-A Franks Tract Complex................................................................................... 4 2-908-A Sand Mound Slough .................................................................................. -

Transitions for the Delta Economy

Transitions for the Delta Economy January 2012 Josué Medellín-Azuara, Ellen Hanak, Richard Howitt, and Jay Lund with research support from Molly Ferrell, Katherine Kramer, Michelle Lent, Davin Reed, and Elizabeth Stryjewski Supported with funding from the Watershed Sciences Center, University of California, Davis Summary The Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta consists of some 737,000 acres of low-lying lands and channels at the confluence of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers (Figure S1). This region lies at the very heart of California’s water policy debates, transporting vast flows of water from northern and eastern California to farming and population centers in the western and southern parts of the state. This critical water supply system is threatened by the likelihood that a large earthquake or other natural disaster could inflict catastrophic damage on its fragile levees, sending salt water toward the pumps at its southern edge. In another area of concern, water exports are currently under restriction while regulators and the courts seek to improve conditions for imperiled native fish. Leading policy proposals to address these issues include improvements in land and water management to benefit native species, and the development of a “dual conveyance” system for water exports, in which a new seismically resistant canal or tunnel would convey a portion of water supplies under or around the Delta instead of through the Delta’s channels. This focus on the Delta has caused considerable concern within the Delta itself, where residents and local governments have worried that changes in water supply and environmental management could harm the region’s economy and residents. -

Workshop Report—Earthquakes and High Water As Levee Hazards in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta

Workshop report—Earthquakes and High Water as Levee Hazards in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta Delta Independent Science Board September 30, 2016 Summary ......................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Workshop ........................................................................................................................................ 1 Scope ........................................................................................................................................... 1 Structure ...................................................................................................................................... 2 Participants and affiliations ........................................................................................................ 2 Highlights .................................................................................................................................... 3 Earthquakes ............................................................................................................................. 3 High water ............................................................................................................................... 4 Perspectives.................................................................................................................................... -

Comparing Futures for the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta

comparing futures for the sacramento–san joaquin delta jay lund | ellen hanak | william fleenor william bennett | richard howitt jeffrey mount | peter moyle 2008 Public Policy Institute of California Supported with funding from Stephen D. Bechtel Jr. and the David and Lucile Packard Foundation ISBN: 978-1-58213-130-6 Copyright © 2008 by Public Policy Institute of California All rights reserved San Francisco, CA Short sections of text, not to exceed three paragraphs, may be quoted without written permission provided that full attribution is given to the source and the above copyright notice is included. PPIC does not take or support positions on any ballot measure or on any local, state, or federal legislation, nor does it endorse, support, or oppose any political parties or candidates for public office. Research publications reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the staff, officers, or Board of Directors of the Public Policy Institute of California. Summary “Once a landscape has been established, its origins are repressed from memory. It takes on the appearance of an ‘object’ which has been there, outside us, from the start.” Karatani Kojin (1993), Origins of Japanese Literature The Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta is the hub of California’s water supply system and the home of numerous native fish species, five of which already are listed as threatened or endangered. The recent rapid decline of populations of many of these fish species has been followed by court rulings restricting water exports from the Delta, focusing public and political attention on one of California’s most important and iconic water controversies. -

Draft Environmental Assessment for the Shiloh Iii Wind Plant Project Habitat Conservation Plan

DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT FOR THE SHILOH III WIND PLANT PROJECT HABITAT CONSERVATION PLAN P REPARED BY: U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service 2800 Cottage Way, W-2650 Sacramento, CA 95825 Contact: Mike Thomas, Chief Habitat Conservation Planning Branch W ITH TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE FROM: ICF International 630 K Street, Suite 400 Sacramento, CA 95814 Contact: Brad Schafer 916.737.3000 February 2011 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2011. Draft Environmental Assessment for the Shiloh III Wind Plant Project Habitat Conservation Plan. February. (ICF 00263.09). Sacramento, CA. With technical assistance from ICF International, Sacramento, CA. Contents Chapter 1 Purpose and Need ........................................................................................................... 1‐1 1.1 Background ................................................................................................................................ 1‐1 1.2 Species Covered by the HCP ...................................................................................................... 1‐2 1.3 Proposed Action Addressed in this EA ....................................................................................... 1‐2 1.4 Purpose of and Need for the Proposed Action .......................................................................... 1‐2 Chapter 2 Proposed Action and Alternatives .................................................................................. 2‐1 2.1 Alternative 1: Proposed Action ................................................................................................. -

Sacramento and Stockton Deep Water Ship Channels Maintenance

1. INTRODUCTION This Introduction section provides information relevant to the other sections of this document and is incorporated by reference into Sections 2 and 3 below. 1.1 Background The National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) prepared the biological opinion (opinion) and incidental take statement portions of this document in accordance with section 7(b) of the Endangered Species Act (ESA) of 1973 (16 USC 1531 et seq.), and implementing regulations at 50 CFR 402. We also completed an essential fish habitat (EFH) consultation on the proposed action, in accordance with section 305(b)(2) of the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act (MSA) (16 U.S.C. 1801 et seq.) and implementing regulations at 50 CFR 600. We completed pre-dissemination review of this document using standards for utility, integrity, and objectivity in compliance with applicable guidelines issued under the Data Quality Act (section 515 of the Treasury and General Government Appropriations Act for Fiscal Year 2001, Public Law 106-554). The document will be available through NMFS’ Public Consultation Tracking System (https://pcts.nmfs.noaa.gov/pcts-web/homepage.pcts). A complete record of this consultation is on file at California Central Valley Area Office in Sacramento, California. 1.2 Consultation History On February 5, 2013, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (Corps) met with NMFS to discuss the development of a biological assessment (BA) to support a pending request for consultation under the ESA. On July 16, 2013, the Corps met with NMFS to further discuss the development of a BA to address the effects of the proposed project. -

Workshop Report—Earthquakes and High Water As Levee Hazards in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta

Workshop report—Earthquakes and High Water as Levee Hazards in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta Delta Independent Science Board September 30, 2016 Summary ......................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Workshop ........................................................................................................................................ 1 Scope ........................................................................................................................................... 1 Structure ...................................................................................................................................... 2 Participants and affiliations ........................................................................................................ 2 Highlights .................................................................................................................................... 3 Earthquakes ............................................................................................................................. 3 High water ............................................................................................................................... 4 Perspectives.................................................................................................................................... -

Historic, Recent, and Future Subsidence, Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, California, USA

UC Davis San Francisco Estuary and Watershed Science Title Historic, Recent, and Future Subsidence, Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, California, USA Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7xd4x0xw Journal San Francisco Estuary and Watershed Science, 8(2) ISSN 1546-2366 Authors Deverel, Steven J Leighton, David A Publication Date 2010 DOI https://doi.org/10.15447/sfews.2010v8iss2art1 Supplemental Material https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7xd4x0xw#supplemental License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California august 2010 Historic, Recent, and Future Subsidence, Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, California, USA Steven J. Deverel1 and David A. Leighton Hydrofocus, Inc., 2827 Spafford Street, Davis, CA 95618 AbStRACt will range from a few cm to over 1.3 m (4.3 ft). The largest elevation declines will occur in the central To estimate and understand recent subsidence, we col- Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta. From 2007 to 2050, lected elevation and soils data on Bacon and Sherman the most probable estimated increase in volume below islands in 2006 at locations of previous elevation sea level is 346,956,000 million m3 (281,300 ac-ft). measurements. Measured subsidence rates on Sherman Consequences of this continuing subsidence include Island from 1988 to 2006 averaged 1.23 cm year-1 increased drainage loads of water quality constitu- (0.5 in yr-1) and ranged from 0.7 to 1.7 cm year-1 (0.3 ents of concern, seepage onto islands, and decreased to 0.7 in yr-1). Subsidence rates on Bacon Island from arability.