Regulations on Access and Property Rights to Natural Resources In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Central America Weather Hazards and Benefits Assessment

The MFEWS Central America Weather Hazards and Benefits Assessment For May 22 – May 28, 2008 1) Many localized areas of the Limon and Heredia provinces of Costa Rica, as well as the San Juan and Atlantic departments of Nicaragua are experiencing a 3-4 dekad late start to the Primera rains. In addition to a below-normal Apante season, the current lack of rainfall has affected April bean harvests, as well as emerging rice and maize crops. Hazards Assessment Text Explanation: Large scale ridging and dry air transport have resulted in the suppression of significant rainfall for much of Central America in the last seven days. The heaviest rainfall totals during the last observation period remained along the Pacific side of Central America, with totals ranging from 30 – 50 mm in the southern highlands of Guatemala and coastal areas near the Gulf of Nicoya in Costa Rica. In El Salvador, Honduras and Nicaragua, little to no rainfall accumulation in the last week has resulted in a continued delayed start of the Primera season in many areas, as precipitation totals have continued to drop further below normal. The Limon and Heredia provinces of Costa Rica, as well as, the Atlantic departments of Nicaragua near the San Juan River, have experienced the worst of the dryness as decreased soil water along the Costa Rica / Nicaragua border may impede the development of bean, rice, and sorghum crops over the next several weeks. Soil moisture deficits have also been felt in localized areas of the Chiriqui province in Panama due to the weak Primera rains. -

Reconstructing the Population History of Nicaragua by Means of Mtdna, Y-Chromosome Strs, and Autosomal STR Markers

AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PHYSICAL ANTHROPOLOGY 143:591–600 (2010) Reconstructing the Population History of Nicaragua by Means of mtDNA, Y-Chromosome STRs, and Autosomal STR Markers Carolina Nun˜ ez,1* Miriam Baeta,1 Cecilia Sosa,1 Yolanda Casalod,1 Jianye Ge,2,3 Bruce Budowle,2,3 and Begon˜ a Martı´nez-Jarreta1 1Laboratory of Forensic Genetics, Faculty of Medicine, University of Zaragoza, 50009 Zaragoza, Spain 2Institute of Investigative Genetics, Health Science Center, University of North Texas, Ft Worth, TX 76107 3Department of Forensic and Investigative Genetics, Health Science Center, University of North Texas, Ft Worth, TX 76107 KEY WORDS Central America; genetic admixture; Mestizos; Native Americans ABSTRACT Before the arrival of the Spaniards in the maternal lineages, whereas the majority of Nicara- Nicaragua, diverse Native American groups inhabited guan Y chromosome haplogroups can be traced back to a the territory. In colonial times, Native Nicaraguan popu- West Eurasian origin. Pairwise Fst distances based on Y- lations interacted with Europeans and slaves from STRs between Nicaragua and European, African and Africa. To ascertain the extent of this genetic admixture Native American populations show that Nicaragua is and provide genetic evidence about the origin of the Nic- much closer to Europeans than the other populations. araguan ancestors, we analyzed the mitochondrial con- Additionally, admixture proportions based on autosomal trol region (HVSI and HVSII), 17 Y chromosome STRs, STRs indicate a predominantly Spanish contribution. and 15 autosomal STRs in 165 Mestizo individuals from Our study reveals that the Nicaraguan Mestizo popula- Nicaragua. To carry out interpopulation comparisons, tion harbors a high proportion of European male and HVSI sequences from 29 American populations were Native American female substrate. -

Leptospirosis Outbreaks in Nicaragua: Identifying Critical Areas and Exploring Drivers for Evidence-Based Planning

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2012, 9, 3883-3910; doi:10.3390/ijerph9113883 OPEN ACCESS International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health ISSN 1660-4601 www.mdpi.com/journal/ijerph Article Leptospirosis Outbreaks in Nicaragua: Identifying Critical Areas and Exploring Drivers for Evidence-Based Planning Maria Cristina Schneider 1,*, Patricia Nájera 1, Sylvain Aldighieri 1, Jorge Bacallao 2, Aida Soto 3, Wilmer Marquiño 3, Lesbia Altamirano 3, Carlos Saenz 4, Jesus Marin 4, Eduardo Jimenez 4, Matthew Moynihan 1 and Marcos Espinal 1 1 Pan American Health Organization, Health Surveillance and Disease Prevention and Control, 525 23rd. St. NW, Washington, DC 20037, USA; E-Mails: [email protected] (P.N.); [email protected] (S.A.); [email protected] (M.M.); [email protected] (M.E.) 2 University of Medical Sciences ofHabana, Research and Reference Center of Atherosclerosis of Havana, Universidad de Ciencias Médicas de La Habana, Tulipán y Panorama, Plaza, La Habana, Cuba; E-Mail: [email protected] 3 Pan American Health Organization Nicaragua, PO Box 1309, Managua, Nicaragua; E-Mails: [email protected] (A.S.); [email protected] (W.M.); [email protected] (L.A.) 4 Ministry of Health of Nicaragua, Costado Oeste Colonia Primero de Mayo, PO Box 107, Managua, Nicaragua; E-Mails: [email protected] (C.S.); [email protected] (J.M.); [email protected] (E.J.) * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-202-974-3190; Fax: +1-202-974-3632. Received: 13 July 2012; in revised form: 21 September 2012 / Accepted: 24 September 2012 / Published: 26 October 2012 Abstract: Leptospirosis is an epidemic-prone zoonotic disease that occurs worldwide. -

Geonomenclature Applicable to European Statistics on International Trade in Goods 2017 Edition Geonomenclature Applicable to European Stat

Geonomenclature applicable to European statistics on international trade in goods 2017 edition Geonomenclature applicable to European stat. on international trade in goods in trade international on stat. European to applicable Geonomenclature 2 017 edition 017 MANUALS AND GUIDELINES Geonomenclature applicable to European statistics on international trade in goods 2017 edition Manuscript completed in October 2017. Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on behalf of the Commission is responsible for the use that might be made of the following information. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2017 © European Union, 2017 Reuse is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. The reuse policy of European Commission documents is regulated by Decision 2011/833/EU (OJ L 330, 14.12.2011, p. 39). Copyright for photographs: © Shutterstock/Hurst Photo For any use or reproduction of photos or other material that is not under the EU copyright, permission must be sought directly from the copyright holders. For more information, please consult: http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/about/policies/copyright The information and views set out in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Neither the European Union institutions and bodies nor any person acting on their behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained therein. Print ISBN 978-92-79-73479-3 ISSN 2363-197X doi:10.2785/588839 KS-GQ-17-011-EN-C PDF ISBN 978-92-79-73478-6 ISSN 2315-0815 doi:10.2785/02445 KS-GQ-17-011-EN-N Contents Contents Contents ........................................................................................................................................................... -

Languages, Countries and Codes (LCCTM)

Date: September 2017 OBJECT MANAGEMENT GROUP Languages, Countries and Codes (LCCTM) Version 1.0 – Beta 2 _______________________________________________ OMG Document Number: ptc/2017-09-04 Standard document URL: http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/1.0/ Normative Machine Consumable File(s): http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/Languages/LanguageRepresentation.rdf http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/201 708 01/Languages/LanguageRepresentation.rdf http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/Languages/ISO639-1-LanguageCodes.rdf http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/201 708 01/Languages/ISO639-1-LanguageCodes.rdf http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/Languages/ISO639-2-LanguageCodes.rdf http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/201 708 01/Languages/ISO639-2-LanguageCodes.rdf http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/Countries/CountryRepresentation.rdf http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/20170801/Countries/CountryRepresentation.rdf http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/Countries/ISO3166-1-CountryCodes.rdf http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/201 708 01/Countries/ISO3166-1-CountryCodes.rdf http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/Countries/ISO3166-2-SubdivisionCodes.rdf http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/201 708 01/Countries/ISO3166-2-SubdivisionCodes.rdf http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/Countries/ UN-M49-RegionCodes .rdf http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/201 708 01/Countries/ UN-M49-Region Codes.rdf http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/201 708 01/Languages/LanguageRepresentation.xml http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/201 708 01/Languages/ISO639-1-LanguageCodes.xml http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/201 708 01/Languages/ISO639-2-LanguageCodes.xml http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/201 708 01/Countries/CountryRepresentation.xml http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/201 708 01/Countries/ISO3166-1-CountryCodes.xml http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/201 708 01/Countries/ISO3166-2-SubdivisionCodes.xml http://www.omg.org/spec/LCC/201 708 01/Countries/ UN-M49-Region Codes. -

Climate Prediction Center's Central America Hazards Outlook June 12

Climate Prediction Center’s Central America Hazards Outlook June 12 – June 18, 2014 Torrential rains due to the remnants of Tropical Storm Boris caused flooding across Guatemala. 3) Extended dry spells and below- average rains have led to substantial 1) Above-average rains over the past seasonal rainfall deficits and poor several weeks have led to high moisture ground conditions in southern Honduras surpluses across much of Guatemala. The and the Chinandega, Madriz and Nueva heavy rains have already caused Segovia and Estelí departments of landslides in the Huehuetenango northern Nicaragua. The drought department and elevated river levels conditions have negatively impacted throughout Guatemala. The potential for corn and coffee production. additional heavy rainfall during the next week is expected to sustain the risk for localized river/flash flooding and landslides in Guatemala. 2) Poorly distributed rainfall since the beginning of March has led to growing moisture deficits and deteriorating ground conditions across several departments in southern Honduras and Nicaragua. Cropping activities could be negatively impacted should rains remain below- average. Abundant rainfall across northern Central America led to flooding during the past week. During the past week, copious amounts of rain (>75mm) were reported across Guatemala, Belize, western Honduras and western El Salvador. The highest precipitation totals were recorded along the Pacific coastline of Guatemala (~300mm in San Jose, Guatemala). The torrential rains caused landslides and flash/river flooding in the Alta Verapaz, Chimaltenango, Solola, Escuintla, Izabal and Petén departments of Guatemala. The past week’s rain followed several weeks of above-average rains which raised rivers above alert level in the Petén, San Marcos, Zacapa, Santa Rosa and Izabal departments of Guatemala and caused landslides in the Huehuetenango department. -

DPCC Country Codes V1.2 (PDF)

DPCC Country Codes List v1.2 DPCC Country Codes List v1.2 - ISO 3166 Standard DPCC State Province Codes List v1.2 - ISO 3166-2 Standard ISO Country Name ISO Country Code NCBI Country Name ISO Country Name ISO Country Code ISO State Province Code ISO State Province Name Afghanistan AFG Afghanistan United States of America USA US-AL Alabama Aland Islands ALA United States of America USA US-AK Alaska Albania ALB Albania United States of America USA US-AZ Arizona Algeria DZA Algeria United States of America USA US-AR Arkansas American Samoa ASM American Samoa United States of America USA US-CA California Andorra AND Andorra United States of America USA US-CO Colorado Angola AGO Angola United States of America USA US-CT Connecticut Anguilla AIA Anguilla United States of America USA US-DE Delaware Antarctica ATA Antarctica United States of America USA US-DC District of Columbia Antigua and Barbuda ATG Antigua and Barbuda United States of America USA US-FL Florida Argentina ARG Argentina United States of America USA US-GA Georgia Armenia ARM Armenia United States of America USA US-HI Hawaii Aruba ABW Aruba United States of America USA US-ID Idaho Australia AUS Australia United States of America USA US-IL Illinois Austria AUT Austria United States of America USA US-IN Indiana Azerbaijan AZE Azerbaijan United States of America USA US-IA Iowa Bahamas BHS Bahamas United States of America USA US-KS Kansas Bahrain BHR Bahrain United States of America USA US-KY Kentucky Bangladesh BGD Bangladesh United States of America USA US-LA Louisiana Barbados -

ABSTRACT Origins of Democracy in Costa Rica and Nicaragua David Lewis Pottinger Director: Dr. Lizbeth Souza-Fuertes, Ph.D. an In

ABSTRACT Origins of Democracy in Costa Rica and Nicaragua David Lewis Pottinger Director: Dr. Lizbeth Souza-Fuertes, Ph.D. An incredible disparity exists between the current political state of affairs in Costa Rica and Nicaragua. Costa Rica is a stable democracy with a high rate of development for its region, while Nicaragua is widely considered to be drifting towards authoritarianism and is one of the poorest countries in the hemisphere. This begs the question: what could possibly account for this divide? After all, Costa Rica and Nicaragua share many aspects of culture and geography. Although the broadness of this question means that innumerable answers could be given, this thesis will attempt to demonstrate that a single factor primarily accounts for these differences: the contrasting outcomes of the “Liberal Reform” period (1821-1909) for the two nations. While Costa Rica began pursuing reforms early and gradually, and was largely free from foreign intervention, Nicaragua was repeatedly stymied in its efforts to modernize, both by internal strife and interference from the United States. APPROVED BY DIRECTOR OF HONORS THESIS: ______________________________________________________ Dr. Lizbeth Souza-Fuertes. Department of Latin-American Studies APPROVED BY THE HONORS PROGRAM: __________________________________________________________________ Dr. Elizabeth Corey, Director DATE: ____________________ ORIGINS OF DEMOCRACY IN COSTA RICA AND NICARAGUA A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Baylor University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Honors Program By David Lewis Pottinger Waco, Texas April 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments . iii Chapter One: An Introduction to Costa Rica, Nicaragua, and Their Shared History . 1 Chapter Two: Reform vs. Anarchy . 13 Chapter Three: Coffee, Foreign Interventionism, and Zelaya. -

William Walker and the Seeds of Progressive Imperialism: the War in Nicaragua and the Message of Regeneration, 1855-1860

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Spring 5-2017 William Walker and the Seeds of Progressive Imperialism: The War in Nicaragua and the Message of Regeneration, 1855-1860 John J. Mangipano University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, Latin American History Commons, Medical Humanities Commons, Military History Commons, Political History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Mangipano, John J., "William Walker and the Seeds of Progressive Imperialism: The War in Nicaragua and the Message of Regeneration, 1855-1860" (2017). Dissertations. 1375. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1375 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WILLIAM WALKER AND THE SEEDS OF PROGRESSIVE IMPERIALISM: THE WAR IN NICARAGUA AND THE MESSAGE OF REGENERATION, 1855-1860 by John J. Mangipano A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School and the Department of History at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Approved: ________________________________________________ Dr. Deanne Nuwer, Committee Chair Associate Professor, History ________________________________________________ Dr. Heather Stur, Committee Member Associate Professor, History ________________________________________________ Dr. Matthew Casey, Committee Member Assistant Professor, History ________________________________________________ Dr. Max Grivno, Committee Member Associate Professor, History ________________________________________________ Dr. Douglas Bristol, Jr., Committee Member Associate Professor, History ________________________________________________ Dr. -

Status and Sustainable Use of Mahogany in Central America

Status and sustainable use of mahogany in Central America Report of a Nicaraguan study and a regional coordination workshop The designation of geographical entities in Published by Fauna & Flora International, this document and the presentation of the Cambridge, UK. material do not imply any expression on the part of the author or Fauna & Flora © 2006 Fauna & Flora International. International concerning the legal status of any country, territory or area, or its Reproduction of any part of the publication authorities, or concerning the delineation of for educational, conservation and other its frontiers or boundaries. non-profit purposes is authorized without prior permission from the copyright Edited by Georgina Magin The opinion of the individual authors does holder, provided that the source is fully not necessarily reflect the opinion of either acknowledged. Cover photos: Juan Pablo Moreiras, FFI the editors or Fauna & Flora International. Reproduction for resale or other commercial A Banson production The authors and Fauna & Flora International purposes is prohibited without prior written 17e Sturton Street take no responsibility for any misrep- permission from the copyright holder. Cambridge CB1 2QG resentation of material from translation of this document into any other language. ISBN: 1 903703 20 4 Printed by Cambridge Printers. Status and sustainable use of mahogany in Central America Report of a Nicaraguan study and a regional coordination workshop Sponsors The project Current situation and harmonization of procedures for the sustainable use of mahogany Swietenia macrophylla in Central America was sup- ported by the Flagship Species Fund of DEFRA (the UK Government Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs). -

Pdf | 413.37 Kb

The MFEWS Central America Weather Hazards and Benefits Assessment For November 27 – December 3, 2008 1) In the last two weeks, heavy rainfall in Costa Rica and Panama has resulted in flooding and rising river levels for local areas in the Limon province and Bocas del Toro region of Panama. The development of a tropical low in the southern Caribbean is expected to produce significant rainfall across the Atlantic regions of Nicaragua, Costa Rica and Panama over the next seven days. Hazards Assessment Text Explanation: Over the last seven days, little to no rainfall was observed across Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador with increased precipitation in excess of 50 mm observed, across local areas in Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Panama. The persistent decrease in weekly rainfall over Guatemala and Honduras continues to provide much needed relief to the flood-affected regions of Guatemala, Honduras and Costa Rica, however anomalously wet conditions in the southern Caribbean have resulted in localized flooding and rising river levels Costa Rica and Panama. Government authorities in Costa Rica have issued an alert for municipalities in Limon province, as roads have been closed and hundreds of residents have been displaced from their homes. Presently, increasing water levels in the Barbilla, Reventazón (Siquirres), Chirripó (Matina) and Parismina Rivers in Costa Rica and Panama continue to be heavily monitored. For the November 27 – December 3 observation period, precipitation models indicate the persistence of a tropical low located in the southern Caribbean. Because this tropical low is forecast to remain quasi-stationary over the next 3-5 days, excessive rainfall totals (> 150 mm) are expected to negatively impact many local areas in the Bocas del Toro, Chiriqui provinces in Panama, the Limon, Puntarenas, Heredia, Alajuela and Cartago provinces of Costa Rica, and Atlantic departments of Nicaragua. -

Fews Net Famine Early Warning Systems Network

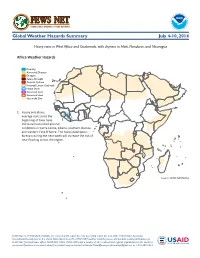

FEWS NET FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS NETWORK Global Weather Hazards Summary July 4-10, 2014 Heavy rains in West Africa and Guatemala, with dryness in Haiti, Honduras, and Nicaragua Africa Weather Hazards Flooding Abnormal Dryness Drought Severe Drought Tropical Cyclone Potential Locust Outbreak Heavy Snow Abnormal Cold Abnormal Heat Seasonally Dry 1. Heavy and above- average rains since the beginning of June have 1 led to oversaturated ground conditions in Sierra Leone, Liberia, southern Guinea, and western Cote D’Ivoire. The heavy downpours forecast during the next week will increase the risk of new flooding across the region. Source: FEWS NET/NOAA FEWS NET is a USAID-funded activity. The content of this report does not necessarily reflect the view of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. The FEWS NET weather hazards process and products include participation by FEWS NET field and home offices, NOAA-CPC, USGS, USDA, NASA, and a number of other national and regional organizations in the countries concerned. Questions or comments about this product may be directed to [email protected], [email protected], or 1-301-683-3424. Weather Hazards Summary July 4-10, 2014 Latin America and the Caribbean Weather Hazards 1. While rains have recently increased over some abnormally dry parts of Hispaniola, southern 1 1 areas remain dry. Long-term moisture deficits due to poor rainfall since the beginning of the year may harm ground conditions across parts of southern Haiti and southwestern Dominican Flooding 2 3 Abnormal Dryness Republic. Drought Severe Drought 2. Above-average rains over the past month have No4 Hazards Tropical Cyclone led to high moisture surpluses across much of Guatemala.