Understanding the Drivers of Subsistence Poaching in the Great

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC Berkeley Working Papers

UC Berkeley Working Papers Title Locality and custom : non-aboriginal claims to customary usufructuary rights as a source of rural protest Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9jf7737p Author Fortmann, Louise Publication Date 1988 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California % LOCALITY AND CUSTOM: NON-ABORIGINAL CLAIMS TO CUSTOMARY USUFRUCTUARY RIGHTS AS A SOURCE OF RURAL PROTEST Louise Fortmann Department of Forestry and Resource Management University of California at Berkeley !mmUTE OF STUDIES'l NOV 1 1988 Of Working Paper 88-27 INSTITUTE OF GOVERNMENTAL STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY LOCALITY AND CUSTOM: NON-ABORIGINAL CLAIMS TO CUSTOMARY USUFRUCTUARY RIGHTS AS A SOURCE OF RURAL PROTEST Louise Fortmann Department of Forestry and Resource Management University of California at Berkeley Working Paper 88-27 November 1988 Institute of Governmental Studies Berkeley, CA 94720 Working Papers published by the Institute of Governmental Studies provide quick dissemination of draft reports and papers, preliminary analyses, and papers with a limited audience. The objective is to assist authors in refining their ideas by circulating research results ana to stimulate discussion about puolic policy. Working Papers are reproduced unedited directly from the author's pages. LOCALITY AND CUSTOM: NON-ABORIGINAL CLAIMS TO CUSTOMARY USUFRUCTUARY RIGHTS AS A SOURCE OF RURAL PROTESTi Louise Fortmann Department of Forestry and Resource Management University of California at Berkeley Between 1983 and 1986, Adamsville, a small mountain community surrounded by national forest, was the site of three protests. In the first, the Woodcutters' Rebellion, local residents protested the imposition of a fee for cutting firewood on national forest land. -

Protecting Folklore Under Modern Intellectual Property Regimes

American University Law Review Volume 48 | Issue 4 Article 2 1999 Protecting Folklore Under Modern Intellectual Property Regimes: A Reappraisal of the Tensions Between Individual and Communal Rights in Africa and the United States Paul Kuruk Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/aulr Part of the Intellectual Property Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Kuruk, Paul. “ Protecting Folklore Under Modern Intellectual Property Regimes: A Reappraisal of the Tensions Between Individual and Communal Rights in Africa and the United States.” American University Law Review 48, no.4 (April, 1999): 769-843. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Protecting Folklore Under Modern Intellectual Property Regimes: A Reappraisal of the Tensions Between Individual and Communal Rights in Africa and the United States Keywords Folklore, Intellectual Property Law, Regional Arrangements This article is available in American University Law Review: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/aulr/vol48/iss4/2 PROTECTING FOLKLORE UNDER MODERN INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY REGIMES: A REAPPRAISAL OF THE TENSIONS BETWEEN INDIVIDUAL AND COMMUNAL RIGHTS IN AFRICA AND THE UNITED STATES * PAUL KURUK TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction.............................................................................................. I. Folklore Under Traditional Systems........................................ 776 A. Nature of Folklore ............................................................. 776 B. Protection Under Customary Law .................................... 780 1. Social groups and rights in folklore ........................... -

Impacts of Wildlife Tourism on Poaching of Greater One-Horned Rhinoceros (Rhinoceros Unicornis) in Chitwan National Park, Nepal

Impacts of Wildlife Tourism on Poaching of Greater One-horned Rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis) in Chitwan National Park, Nepal A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Applied Science (Parks, Tourism and Ecology) at Lincoln University by Ana Nath Baral Lincoln University 2013 Abstract of a thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Applied Science (Parks, Tourism and Ecology) Abstract Impacts of Wildlife Tourism on Poaching of Greater One-horned Rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis) in Chitwan National Park, Nepal by Ana Nath Baral Chitwan National Park (CNP) is one of the most important global destinations to view wildlife, particularly rhinoceros. The total number of wildlife tourists visiting the park has increased from 836 in Fiscal Year (FY) 1974/75 to 172,112 in FY 2011/12. But the rhinoceros, the main attraction for the tourists, is seriously threatened by poaching for its horn (CNP, 2012). Thus, the study of the relationship between wildlife tourism and rhinoceros poaching is essential for the management of tourism and control of the poaching. This research identifies the impacts of tourism on the poaching. It documents the relationships among key indicators of tourism and poaching in CNP. It further interprets the identified relationships through the understandings of local wildlife tourism stakeholders. Finally, it suggests future research and policy, and management recommendations for better management of tourism and control of poaching. Information was collected using both quantitative and qualitative research approaches. Data were collected focussing on the indicators of the research hypotheses which link tourism and poaching. -

The “Ill Kill'd” Deer: Poaching and Social Order in the Merry Wives of Windsor

The “ill kill’d” Deer: Poaching and Social Order in The Merry Wives of Windsor Jeffrey Theis Nicholas Rowe once asserted that the young Shakespeare was caught stealing a deer from Sir Thomas Lucy’s park at Charlecote. The anecdote’s truth-value is clearly false, yet the narrative’s plausibility resonates from the local social customs in Shakespeare’s Warwickshire region. As the social historian Roger Manning convincingly argues, hunting and its ille- gitimate kin poaching thoroughly pervaded all social strata of early modern English culture. Close proximity to the Forest of Arden and nu- merous aristocratic deer parks and rabbit warrens would have steeped Shakespeare’s early life in the practices of hunting and poaching whether he engaged in them or only heard stories about them.1 While some Shakespeare criticism attends directly or indirectly to the importance of hunting in the comedies, remarkably, there has been no sustained analysis of poaching’s importance in these plays.2 In part, the reason for the oversight might be lexicographical. The word “poaching” never occurs in any of Shakespeare’s works, and the first instance in which poaching means “to take game or fish illegally” is in 1611—a decade after Shakespeare composed his comedies.3 Yet while the word was not coined for another few years, Roger Manning proves that illegal deer killing was a socially and politically explosive issue well before 1611. Thus, the “ill kill’d deer” Justice Shallow refers to in Act One of The Merry Wives of Windsor situates the play within a socially resonant discourse where illegal deer killing brings to light cultural assumptions imbedded within the legal hunt. -

Bartolomé De Las Casas, Soldiers of Fortune, And

HONOR AND CARITAS: BARTOLOMÉ DE LAS CASAS, SOLDIERS OF FORTUNE, AND THE CONQUEST OF THE AMERICAS Dissertation Submitted To The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in Theology By Damian Matthew Costello UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON Dayton, Ohio August 2013 HONOR AND CARITAS: BARTOLOMÉ DE LAS CASAS, SOLDIERS OF FORTUNE, AND THE CONQUEST OF THE AMERICAS Name: Costello, Damian Matthew APPROVED BY: ____________________________ Dr. William L. Portier, Ph.D. Committee Chair ____________________________ Dr. Sandra Yocum, Ph.D. Committee Member ____________________________ Dr. Kelly S. Johnson, Ph.D. Committee Member ____________________________ Dr. Anthony B. Smith, Ph.D. Committee Member _____________________________ Dr. Roberto S. Goizueta, Ph.D. Committee Member ii ABSTRACT HONOR AND CARITAS: BARTOLOMÉ DE LAS CASAS, SOLDIERS OF FORTUNE, AND THE CONQUEST OF THE AMERICAS Name: Costello, Damian Matthew University of Dayton Advisor: Dr. William L. Portier This dissertation - a postcolonial re-examination of Bartolomé de las Casas, the 16th century Spanish priest often called “The Protector of the Indians” - is a conversation between three primary components: a biography of Las Casas, an interdisciplinary history of the conquest of the Americas and early Latin America, and an analysis of the Spanish debate over the morality of Spanish colonialism. The work adds two new theses to the scholarship of Las Casas: a reassessment of the process of Spanish expansion and the nature of Las Casas’s opposition to it. The first thesis challenges the dominant paradigm of 16th century Spanish colonialism, which tends to explain conquest as the result of perceived religious and racial difference; that is, Spanish conquistadors turned to military force as a means of imposing Spanish civilization and Christianity on heathen Indians. -

Legal Issues in Austen's Life and Novels

DePaul Journal of Art, Technology & Intellectual Property Law Volume 27 Issue 2 Spring 2017 Article 2 Reading Jane Austen through the Lens of the Law: Legal Issues in Austen's Life and Novels Maureen B. Collins Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jatip Part of the Computer Law Commons, Cultural Heritage Law Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, Intellectual Property Law Commons, Internet Law Commons, and the Science and Technology Law Commons Recommended Citation Maureen B. Collins, Reading Jane Austen through the Lens of the Law: Legal Issues in Austen's Life and Novels, 27 DePaul J. Art, Tech. & Intell. Prop. L. 115 (2019) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jatip/vol27/iss2/2 This Lead Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Journal of Art, Technology & Intellectual Property Law by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Collins: Reading Jane Austen through the Lens of the Law: Legal Issues in READING JANE AUSTEN THROUGH THE LENS OF THE LAW: LEGAL ISSUES IN AUSTEN'S LIFE AND NOVELS Maureen B. Collins I. INTRODUCTION Jane Austen is most closely associated with loves lost and found and vivid depictions of life in Regency England. Austen's heroines have served as role models for centuries to young women seeking to balance manners and moxie. Today, Austen's characters have achieved a popularity she could have never foreseen. There is an "Austen industry" of fan fiction, graphic novels, movies, BBC specials, and Austen ephemera. -

The Status of Poaching in the United States - Are We Protecting Our Wildlife

Volume 33 Issue 4 Wildlife Law and Policy Issues Fall 1993 The Status of Poaching in the United States - Are We Protecting Our Wildlife Ruth S. Musgrave Sara Parker Miriam Wolok Recommended Citation Ruth S. Musgrave, Sara Parker & Miriam Wolok, The Status of Poaching in the United States - Are We Protecting Our Wildlife, 33 Nat. Resources J. 977 (1993). Available at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nrj/vol33/iss4/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Natural Resources Journal by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. RUTH S. MUSGRAVE, SARA PARKER AND MIRIAM WOLOK* The Status Of Poaching In The United States-Are We Protecting Our Wildlife?** ABSTRACT Poachingactivities in the United States are on the rise, deplet- ing both game and nongame wildlife. Federal laws for protection of wildlife, such as the Lacey Act and the Endangered Species Act, provide some muscle to enforcement efforts, but it is largely the states that must bear the brunt of enforcement of wildlife laws. This article describes the extent of the poaching problem in the United States and compares various types of state laws that can impact poaching. Interviews of enforcement officers in the field and original research regarding the content of and differences be- tween state laws yield an array of proposed solutions and recom- mendationsfor action. Among the recommendationsare education of the judiciary and prosecuting attorneys, and making state laws consistent in their enforcement of wildlife protection policy. -

The Camouflaged Crime: Perceptions of Poaching in Southern Appalachia

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2021 The Camouflaged Crime: erP ceptions of Poaching in Southern Appalachia Randi Miller East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Miller, Randi, "The Camouflaged Crime: erP ceptions of Poaching in Southern Appalachia" (2021). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3919. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/3919 This Thesis - unrestricted is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Camouflaged Crime: Perceptions of Poaching in Southern Appalachia ________________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of Criminal Justice East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Criminal Justice ______________________ by Randi Marie Miller May 2021 _____________________ Dustin Osborne, Ph.D., Chair Larry Miller, Ph.D. Chris Rush, Ph.D. Keywords: conservation officers, poaching, southern appalachia, rural crime ABSTRACT The Camouflaged Crime: Perceptions of Poaching in Southern Appalachia by Randi Marie Miller The purpose of this study was to explore perceptions of poaching within the Southern Appalachian Region. To date, little research has been conducted on the general topic of poaching and no studies have focused on this Region. Several research questions were pursued, including perceptions of poacher motivations, methods and concern regarding apprehension and punishment. -

Crimes Against the Wild: Poaching in California

CRIMES AGAINST THE WILD: POACHING IN CALIFORNIA by KEVIN HANSEN and the MOUNTAIN LION FOUNDATION JULY 1994 Mountain Lion Foundation, P.O. Box 1896, Sacramento, CA 95812 (916) 442-2666 Foreword by Mark J. Palmer iii Acknowledgments iv Methods v SECTION I- The Crime of Poaching 1 Poaching Defined 3 Who Poaches? 3 Profile of a Noncommercial Poacher 4 Ethnic Factors in Poaching 5 Why Poach? 6 Noncommercial Poaching 6 Commercial Poaching 7 How Poachers Poach 11 Noncommercial Poaching 11 Commercial Poaching 12 Impacts of Poaching 13 Public Perception of Poaching 17 SECTION II - Wildlife Law Enforcement 21 \Vildlife Laws and Regulations 21 State Laws 21 Federal Laws 23 Law Enforcement Agencies 26 To Catch a Poacher 28 Undercover Operations 32 To Convict a Poacher 34 Ominous Trends in Poaching Enforcement 38 A Final Note 42 SECTION III - Recommendations 44 Legislation 44 Law Enforcement 48 Education 49 Public Education 49 Education of Judges and Prosecutors 50 Research 51 Bibliography 53 n 1986, the Mountain Lion Founda Foundation since 1990 has been to imple tion was formed by a group of dedi ment Proposition 117, which in the first three cated conservationists. Since the years has already led to acquisition of over 1960s, a group of individuals and or 128,000 acres of wildlife habitat and enhance ganizations in California called the ment of over 870 miles of streams and riv Mountain Lion Coalition had been protect ers. Proposition 117 also addressed the ing mountain lions from exploitation. While poaching threat in part, raising maximum the Mountain Lion Coalition was successful fines for illegal killing of mountain lions from in banning bounties on mountain lions (1963) $1,000 to $10,000. -

Journal of International Wildlife Law & Policy Poaching Cultural Property

This article was downloaded by: [Stetson University] On: 19 June 2015, At: 09:07 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Journal of International Wildlife Law & Policy Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/uwlp20 Poaching Cultural Property: Invoking Cultural Property Law to Protect Elephants Ethan Arthura a Stetson University College of Law, Gulfport, Florida Published online: 09 Dec 2014. Click for updates To cite this article: Ethan Arthur (2014) Poaching Cultural Property: Invoking Cultural Property Law to Protect Elephants, Journal of International Wildlife Law & Policy, 17:4, 231-253, DOI: 10.1080/13880292.2014.957029 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13880292.2014.957029 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

International Illegal Trade in Wildlife: Threats and U.S

International Illegal Trade in Wildlife: Threats and U.S. Policy Liana Sun Wyler Analyst in International Crime and Narcotics Pervaze A. Sheikh Specialist in Natural Resources Policy July 23, 2013 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL34395 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress International Illegal Trade in Wildlife: Threats and U.S. Policy Summary Global trade in illegal wildlife is a potentially vast illicit economy, estimated to be worth billions of dollars each year. Some of the most lucrative illicit wildlife commodities include elephant ivory, rhino horn, sturgeon caviar, and so-called “bushmeat.” Wildlife smuggling may pose a transnational security threat as well as an environmental one. Numerous sources indicate that some organized criminal syndicates, insurgent groups, and foreign military units may be involved in various aspects of international wildlife trafficking. Limited anecdotal evidence also indicates that some terrorist groups may be engaged in wildlife crimes, particularly poaching, for monetary gain. Some observers claim that the participation of such actors in wildlife trafficking can therefore threaten the stability of countries, foster corruption, and encourage violence to protect the trade. Reports of escalating exploitation of protected wildlife, coupled with the emerging prominence of highly organized and well-equipped illicit actors in wildlife trafficking, suggests that policy challenges persist. Commonly cited challenges include legal loopholes that allow poachers and traffickers to operate with impunity, gaps in foreign government capabilities to address smuggling problems, and persistent structural drivers such as lack of alternative livelihoods in source countries and consumer demand. To address the illicit trade in endangered wildlife, the international community has established, through the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), a global policy framework to regulate and sometimes ban exports of selected species. -

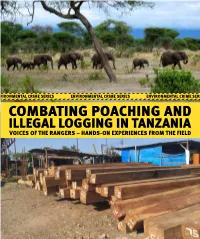

Combating Poaching and Illegal Logging in Tanzania Voices of the Rangers – Hands-On Experiences from the Field

ENVIRONMENTAL CRIME SERIES ENVIRONMENTAL CRIME SERIES ENVIRONMENTAL CRIME SERIES COMBATING POACHING AND ILLEGAL LOGGING IN TANZANIA VOICES OF THE RANGERS – HANDS-ON EXPERIENCES FROM THE FIELD 1 Editorial Team Frode Smeby, Consultant, GRID-Arendal Rune Henriksen, Consultant, GRID-Arendal Christian Nellemann, GRID-Arendal (Current address: Rhipto Rapid Response Unit, Norwegian Center for Global Analyses) Contributors Benjamin Kijika, Commander, Lake Zone Anti-Poaching Unit Rosemary Kweka, Pasiansi Wildlife Institute Lupyana Mahenge, Lake Zone Anti-Poaching Unit Valentin Yemelin, GRID-Arendal Luana Karvel, GRID-Arendal Anonymous law enforcement officers from across Tanzania. The rangers have been anonymized in order to protect them from the risk of retributions. The authors gratefully acknowledge the sharing of information and experiences by these rangers, who risk their lives every day in the name of conservation. Cartography Riccardo Pravettoni All photos © Frode Smeby and Rune Henriksen Norad is gratefully acknowledged for providing the necessary ENVIRONMENTAL CRIME SERIES funding for the project and the production of this publication. 2 COMBATING POACHING AND ILLEGAL LOGGING IN TANZANIA VOICES OF THE RANGERS – HANDS-ON EXPERIENCES FROM THE FIELD EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 WILDLIFE CRIME 6 ILLEGAL LOGGING 9 CHARCOAL 10 GENERAL INTRODUCTION 12 WILDLIFE CRIME 15 EXPERIENCES 16 CHALLENGES 17 SITUATION OF THE LAKE ZONE ANTI-POACHING UNIT 21 FIELD EVALUATION OF LAKE ZONE ANTI-POACHING UNIT 23 UGALLA GAME RESERVE 29 ILLEGAL LOGGING 35 CORRUPTION AND