Toward Traditional Resource Rights for Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities Darrell A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Amazonian Travels of Richard Evans Schultes Introduction: Early Life and Explorations

The Amazonian Travels of Richard Evans Schultes Introduction: Early Life and Explorations By Brian Hettler and Mark Plotkin April 8, 2019 The following text is from the interactive map available at the link: banrepcultural.org/schultes Introduction Richard Evans Schultes – ethnobotanist, taxonomist, writer and photographer – is regarded as one of the most important plant explorers of the 20th century. In December 1941, Schultes entered the Amazon rainforest on a mission to study how indigenous peoples used plants for medicinal, ritual and practical purposes. He went on to spend over a decade immersed in near-continuous fieldwork, becoming one of the most important plant explorers of the 20th century. Schultes’ area of focus was the northwest Amazon, an area that had remained largely unknown to the outside world, isolated by the Andes to the west and dense jungles and impassable rapids on all other sides. In this remote area, Schultes lived amongst little studied tribes, mapped uncharted rivers, and was the first scientist to explore some areas that have not been researched since. His notes and photographs are some of the only existing documentation of indigenous cultures in a region of the Amazon on the cusp of change. In this interactive map journal, retrace Schultes’ extraordinary adventures and experience the thrill of scientific exploration and discovery. Through a series of interactive maps, explore the magical landscapes and indigenous cultures of the Amazon Rainforest, presented through the lens of Schultes’ vivid photography and ethnobotanical research. 1 Early Life in Boston Richard Evans Schultes was born in Boston, Massachusetts on January 12, 1915. -

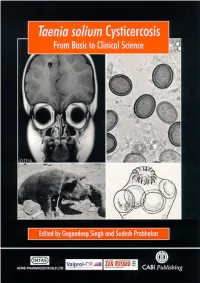

Singh - Prelims 17/9/02 12:00 Pm Page I

Singh - Prelims 17/9/02 12:00 pm Page i Taenia solium Cysticercosis From Basic to Clinical Science Singh - Prelims 17/9/02 12:00 pm Page ii Singh - Prelims 17/9/02 12:00 pm Page iii Taenia solium Cysticercosis From Basic to Clinical Science Edited by Gagandeep Singh Dayanand Medical College & Hospital Ludhiana Punjab, India and Sudesh Prabhakar Department of Neurology Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research Chandigarh, India CABI Publishing Singh - Prelims 17/9/02 12:00 pm Page iv CABI Publishing is a division of CAB International CABI Publishing CABI Publishing CAB International 10 E 40th Street Wallingford Suite 3203 Oxon OX10 8DE New York, NY 10016 UK USA Tel: +44 (0)1491 832111 Tel: +1 212 481 7018 Fax: +44 (0)1491 833508 Fax: +1 212 686 7993 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.cabi-publishing.org © CAB International 2002. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronically, mechanically, by photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owners. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library, London, UK. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Singh, G. (Gagandeep) Taenia solium cysticercosis : from basic to clinical science / edited by G. Singh and S. Prabhakar. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-85199-628-0 1. Cysticercosis. 2. Taenia. I. Prabhakar, S. (Sudesh) II. Title. RC136.7 .S545 2002 616.9’64--dc21 2002001332 ISBN 0 85199 628 0 Typeset in Palatino by Columns Design Ltd, Reading, UK Printed and bound in the UK by Biddles Ltd, Guildford and Kings Lynn. -

Vol. II ETHNOPHARMACOLOGIC SEARCH for PSYCHOACTIVE

ETHNOPHARMACOLOGIC SEARCH for PSYCHOACTIVE DRUGS • 2017 50th Anniversary Symposium › June 6 – 8, 2017 ESPD50.com Vol. II Table of Contents Foreword by Sir Ghillean Prance 1 Scientific Director of the Eden Project, Director (Ret.), Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew [Introduction] What a Long, Strange Trip it’s Been: Reflections on the Ethnopharmacologic Search for Psychoactive Drugs (1967-2017) 2 Dennis McKenna [From the Archive] A Scientist Looks at the Hippies 10 Stephen Szára AYAHUASCA & THE AMAZON 23 Ayahuasca: A Powerful Epistemological Wildcard in a Complex, Fascinating and Dangerous World 24 Luis Eduardo Luna From Beer to Tobacco: A Probable Prehistory of Ayahuasca and Yagé 36 Constantino Manuel Torres Plant Use and Shamanic Dietas in Contemporary Ayahuasca Shamanism in Peru 55 Evgenia Fotiou Spirit Bodies, Plant Teachers and Messenger Molecules in Amazonian Shamanism 70 Glenn H. Shepard Broad Spectrum Roles of Harmine in Ayahuasca 82 Dale Millard Viva Schultes - A Retrospective [Keynote] 95 Mark J. Plotkin, Brian Hettler & Wade Davis AFRICA, AUSTRALIA & SOUTHEAST ASIA 121 Kabbo’s !Kwaiń: The Past, Present and Possible Future of Kanna 122 Nigel Gericke Kratom (Mitragyna speciosa) as a Potential Therapy for Opioid Dependence 151 Christopher R. McCurdy The Ibogaine Project: Urban Ethnomedicine for Opioid Use Disorder 160 Kenneth Alper Psychoactive Initiation Plant Medicines: Their Role in the Healing and Learning Process of South African and Upper Amazonian Traditional Healers 175 Jean-Francois Sobiecki Psychoactive Australian Acacia Species and Their Alkaloids 181 Snu Voogelbreinder From ‘There’ to ‘Here’: Psychedelic Natural Products and Their Contributions to Medicinal Chemistry [Keynote] 202 David E. Nichols MEXICO & CENTRAL AMERICA 219 Fertile Grounds? – Peyote and the Human Reproductive System 220 Stacy B. -

UC Berkeley Working Papers

UC Berkeley Working Papers Title Locality and custom : non-aboriginal claims to customary usufructuary rights as a source of rural protest Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9jf7737p Author Fortmann, Louise Publication Date 1988 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California % LOCALITY AND CUSTOM: NON-ABORIGINAL CLAIMS TO CUSTOMARY USUFRUCTUARY RIGHTS AS A SOURCE OF RURAL PROTEST Louise Fortmann Department of Forestry and Resource Management University of California at Berkeley !mmUTE OF STUDIES'l NOV 1 1988 Of Working Paper 88-27 INSTITUTE OF GOVERNMENTAL STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY LOCALITY AND CUSTOM: NON-ABORIGINAL CLAIMS TO CUSTOMARY USUFRUCTUARY RIGHTS AS A SOURCE OF RURAL PROTEST Louise Fortmann Department of Forestry and Resource Management University of California at Berkeley Working Paper 88-27 November 1988 Institute of Governmental Studies Berkeley, CA 94720 Working Papers published by the Institute of Governmental Studies provide quick dissemination of draft reports and papers, preliminary analyses, and papers with a limited audience. The objective is to assist authors in refining their ideas by circulating research results ana to stimulate discussion about puolic policy. Working Papers are reproduced unedited directly from the author's pages. LOCALITY AND CUSTOM: NON-ABORIGINAL CLAIMS TO CUSTOMARY USUFRUCTUARY RIGHTS AS A SOURCE OF RURAL PROTESTi Louise Fortmann Department of Forestry and Resource Management University of California at Berkeley Between 1983 and 1986, Adamsville, a small mountain community surrounded by national forest, was the site of three protests. In the first, the Woodcutters' Rebellion, local residents protested the imposition of a fee for cutting firewood on national forest land. -

Protecting Folklore Under Modern Intellectual Property Regimes

American University Law Review Volume 48 | Issue 4 Article 2 1999 Protecting Folklore Under Modern Intellectual Property Regimes: A Reappraisal of the Tensions Between Individual and Communal Rights in Africa and the United States Paul Kuruk Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/aulr Part of the Intellectual Property Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Kuruk, Paul. “ Protecting Folklore Under Modern Intellectual Property Regimes: A Reappraisal of the Tensions Between Individual and Communal Rights in Africa and the United States.” American University Law Review 48, no.4 (April, 1999): 769-843. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Protecting Folklore Under Modern Intellectual Property Regimes: A Reappraisal of the Tensions Between Individual and Communal Rights in Africa and the United States Keywords Folklore, Intellectual Property Law, Regional Arrangements This article is available in American University Law Review: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/aulr/vol48/iss4/2 PROTECTING FOLKLORE UNDER MODERN INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY REGIMES: A REAPPRAISAL OF THE TENSIONS BETWEEN INDIVIDUAL AND COMMUNAL RIGHTS IN AFRICA AND THE UNITED STATES * PAUL KURUK TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction.............................................................................................. I. Folklore Under Traditional Systems........................................ 776 A. Nature of Folklore ............................................................. 776 B. Protection Under Customary Law .................................... 780 1. Social groups and rights in folklore ........................... -

16.03.11 Specific Instance – Survival International V. Salini Impregilo No Firma

SURVIVAL INTERNATIONAL CHARITABLE TRUST Complainant v SALINI IMPREGILO S.P.A Respondent ________________________________________________ SPECIFIC INSTANCE ________________________________________________ Acronyms ACHPR The African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights CESI Centro Elettrotecnico Sperimentale Italiano S.p.A. Charter The Charter of African Human and Peoples Rights DAG Development Assistance Group Downstream Communities The Bodi, Mursi, Kwegu, Kara, Nyangatom and Dassanach peoples of the Lower Omo and the Turkana, Elmolo, Gabbra, Rendille and Samburu of Lake Turkana EEPCo Ethiopian Electric Power Corporation EIA Environmental Impact Assessment 2006 ESIA Environmental and Social Impact Assessment 2008 EPA Environmental Protection Agency of Ethiopia FPIC Free prior and informed consent Governments The Governments of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia and the Republic of Kenya Guidelines OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises MNE Multinational Enterprise NCP National Contact Point The Project Construction of the Gibe III dam Salini Salini Impregilo S.p.A. Survival Survival International Italia WCD World Commission on Dams 1 I Introduction1 Parties 1. For over 40 years Survival International has been the global movement for tribal rights, with over 250,000 supporters in almost 100 countries. It is a recipient of the Right Livelihood Award and enjoys observer status at a number of international organisations. Survival International Italia is our Italian office. 2. We have lodged this complaint under the OECD Guidelines on behalf of the tribal peoples of the Lower Omo in southwest Ethiopia and of Lake Turkana in Kenya (“the downstream communities”). 3. The Lower Omo peoples include the Mursi, the Bodi and the Kwegu, the Kara, the Nyangatom and the Dassanach. They number more than 100,000. -

Impacts of Wildlife Tourism on Poaching of Greater One-Horned Rhinoceros (Rhinoceros Unicornis) in Chitwan National Park, Nepal

Impacts of Wildlife Tourism on Poaching of Greater One-horned Rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis) in Chitwan National Park, Nepal A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Applied Science (Parks, Tourism and Ecology) at Lincoln University by Ana Nath Baral Lincoln University 2013 Abstract of a thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Applied Science (Parks, Tourism and Ecology) Abstract Impacts of Wildlife Tourism on Poaching of Greater One-horned Rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis) in Chitwan National Park, Nepal by Ana Nath Baral Chitwan National Park (CNP) is one of the most important global destinations to view wildlife, particularly rhinoceros. The total number of wildlife tourists visiting the park has increased from 836 in Fiscal Year (FY) 1974/75 to 172,112 in FY 2011/12. But the rhinoceros, the main attraction for the tourists, is seriously threatened by poaching for its horn (CNP, 2012). Thus, the study of the relationship between wildlife tourism and rhinoceros poaching is essential for the management of tourism and control of the poaching. This research identifies the impacts of tourism on the poaching. It documents the relationships among key indicators of tourism and poaching in CNP. It further interprets the identified relationships through the understandings of local wildlife tourism stakeholders. Finally, it suggests future research and policy, and management recommendations for better management of tourism and control of poaching. Information was collected using both quantitative and qualitative research approaches. Data were collected focussing on the indicators of the research hypotheses which link tourism and poaching. -

Anthropology 213 Ethnobotany: Plants & Peoples

ANTHROPOLOGY 213 ETHNOBOTANY: PLANTS & PEOPLES BULLETIN INFORMATION ANTH 213 – Ethnobotany: Plants and Peoples (3 credit hours) Course Description: Anthropological overview of the interactions between cultures around the world and the plants that affect them, from cultural, biological, archaeological, and linguistic points of view. SAMPLE COURSE OVERVIEW Every culture depends on plants for needs as diverse as food, shelter, clothing, and medicines. Certain plants hold symbolic meanings for people. Plants affect people in many ways. Ethnobotany—the interrelationships between cultures and plants—is a field of study by disciplines as diverse as anthropology, botany, chemistry, pharmacognosy, and engineering. This course provides students with a multi-cultural overview of human-plant interactions through the lenses of the four anthropological subfields of cultural anthropology, biological anthropology, linguistics, and archaeology. No background in either anthropology or botany is needed, just a curiosity to learn more about human-plant relationships. The emphasis is on cultural anthropology: students participate in a class research project on an ethnobotanical subject. ITEMIZED LEARNING OUTCOMES Upon successful completion of ANTH 213, students will be able to: 1. Define ethnobotany; 2. List the subfields of anthropology and summarize how each intersects with ethnobotany; 3. Outline differences in worldviews and how those affect human-nature relationships; 4. Summarize important ethnobotanical issues; 5. Give examples of ethical responsibilities in human subject research; 6. Be professionally and nationally CITI certified for human subject research; 7. Conduct an oral interview; 8. Apply the scientific method by stating a testable hypothesis, researching the topic, compiling data, and evaluating the findings. SAMPLE REQUIRED TEXTS/SUGGESTED READINGS/MATERIALS No textbook. -

A Unified Concept of Population Transfer

Denver Journal of International Law & Policy Volume 21 Number 1 Fall Article 4 May 2020 A Unified Concept of opulationP Transfer Christopher M. Goebel Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/djilp Recommended Citation Christopher M. Goebel, A Unified Concept of Population Transfer, 21 Denv. J. Int'l L. & Pol'y 29 (1992). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Denver Journal of International Law & Policy by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. A Unified Concept of Population Transfer CHRISTOPHER M. GOEBEL* Population transfer is an issue arising often in areas of ethnic ten- sion, from Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina to the Western Sahara, Tibet, Cyprus, and beyond. There are two forms of human population transfer: removals and settlements. Generally, commentators in interna- tional law have yet to discuss the two together as a single category of population transfer. In discussing the prospects for such a broad treat- ment, this article is a first to compare and contrast international law's application to removals and settlements. I. INTRODUCTION International attention is focusing on uprooted people, especially where there are tensions of ethnic proportions. The Red Cross spent a significant proportion of its budget aiding what it called "displaced peo- ple," removed en masse from their abodes. Ethnic cleansing, a term used by the Serbs, was a process of population transfer aimed at removing the non-Serbian population from large areas of Bosnia-Herzegovina.2 The large-scale Jewish settlements into the Israeli-occupied Arab territories continue to receive publicity. -

Mass Displacement in Post-Catastrophic Societies: Vulnerability, Learning, and Adaptation in Germany and India, 1945–1952

Futures That Internal Migration Place-Specifi c Introduction Never Were and the Left Material Resources MASS DISPLACEMENT IN POST-CATASTROPHIC SOCIETIES: VULNERABILITY, LEARNING, AND ADAPTATION IN GERMANY AND INDIA, 1945–1952 Avi Sharma The summer of 1945 in Germany was exceptional. Displaced persons (UN DPs), refugees, returnees, ethnic German expellees (Vertriebene)1 and soldiers arrived in desperate need of care, including food, shelter, medical attention, clothing, bedding, shoes, cooking utensils, and cooking fuel. An estimated 7.3 million people transited to or through Berlin between July 1945 and March 1946.2 In part because of its geographical location, Berlin was an extreme case, with observers estimating as many as 30,000 new arrivals per day. However, cities across Germany were swollen with displaced persons, starved of es- sential supplies, and faced with catastrophic housing shortages. During that time, ethnic, religious, and linguistic “others” were frequently conferred legal privileges, while ethnic German expellees and internally displaced persons (IDPs) were disadvantaged by the occupying forces. How did refugees, returnees, DPs, IDPs and other migrants navigate the fractured governmentality and allocated scar- city of the postwar regime? How did survivors survive the postwar? The summer of 1947 in South Asia was extraordinary in diff erent ways.3 Faced with a hastily organized division of the Indian sub- continent into India and Pakistan (known as the Partition), between 10 and 14 million Muslims, Sikhs, and Hindus crossed borders in a period of only a few months. Estimates put the one-day totals for 2 Angelika Königseder, cross-border movement as high as 400,000, and data on mortality Flucht nach Berlin: Jüdische Displaced Persons 1945– 4 range between 200,000 and 2 million people killed. -

Factory Schools Destroying Indigenous People in the Name of Education

For tribes, for nature, for all humanity A Survival International Report Factory Schools Destroying indigenous people in the name of education Whoever controls the education of our children controls our future Wilma Mankiller Cherokee, U.S. Contents Introduction 03 Chapter 1: Historic Factory Schooling 04 Historic Factory Schooling 05 Killing the child 07 Dividing the family 09 Destroying the tribe 10 Leaving a devastating legacy 13 Case study 1: Denmark 15 Case study 2: Canada 16 Chapter 2: Factory Schooling today 18 Tribal & indigenous Factory Schooling today 19 Killing the child 20 Dividing the family 22 Destroying the tribe 24 Going to school can prevent learning 27 Going to school often provides only low quality learning 28 Case study 3: Malaysia 31 Case study 4: Botswana 32 Case study 5: Indonesia 35 Case study 6: French Guiana 36 Chapter 3: Prejudice 37 Prejudice in schooling policy and practice 38 “Unschooled means uneducated” 39 “School should be compulsory” 40 “Schooling should follow a single model” 41 Chapter 4: Control 42 Schooling as a means of control 43 Control over land and resources 44 Control over people 46 Case study 7: India – adopted by a steel company 47 Case study 8: India – the world’s largest tribal school 48 Chapter 5: Resistance, self-determination and indigenous 49 education Towards the future 50 Reclaiming indigenous languages in education 51 Education and self-determination 53 Chapter 6: A call to action 54 Education that respects indigenous peoples’ rights 55 Case study 9: Brazil – Yanomami 56 Case study 10: Canada 57 Case study 11: Brazil – Enawene Nawe 58 Case study 12: Mexico 60 Case study 13: Indonesia 61 Case study 14: Australia 62 Case study 15: U.S. -

Forced Population Transfers Resolve Self-Determination Conflicts?

Can Forced Population Transfers Resolve Self-determination Conflicts? A European Perspective Stefan Wolff Department of European Studies University of Bath Bath BA2 7AY England, UK [email protected] Introduction Self-determination conflicts are among the most violent forms of civil wars that can engulf modern societies. As they are in most cases linked to claims of ethnic, religious, linguistic or otherwise defined groups for secession from, or for political domination in, an existing state they also have repercussions on regional and international stability. Self-determination conflicts can be observed on all continents. Not all of them are violent, but most have a clear potential for violent escalation and are therefore an important concern for international and regional governmental organisations seeking to preserve peace and stability. However, the capacity of organisations like the UN, the OSCE and the EU to do so has only gradually developed over the past decade and is still a far cry from being sufficient. In the past and present, states (and population groups within them) have therefore felt that they had been and are left to their own devices when it comes to preserving their internal stability and external security. The largely incongruent political and ethnic maps of Europe have meant that self- determination conflicts on this continent have mostly taken the form of ethnic conflicts: from Northern Ireland to the Caucasus, from the Basque country to the Åland islands and from Kosovo to Silesia the competing claims of distinct ethnic groups to self-determination have been the most prominent sources of conflicts within and across state boundaries.