Liquidity Costs in Futures Options Markets by Samarth Shah, B. Wade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Section 1256 and Foreign Currency Derivatives

Section 1256 and Foreign Currency Derivatives Viva Hammer1 Mark-to-market taxation was considered “a fundamental departure from the concept of income realization in the U.S. tax law”2 when it was introduced in 1981. Congress was only game to propose the concept because of rampant “straddle” shelters that were undermining the U.S. tax system and commodities derivatives markets. Early in tax history, the Supreme Court articulated the realization principle as a Constitutional limitation on Congress’ taxing power. But in 1981, lawmakers makers felt confident imposing mark-to-market on exchange traded futures contracts because of the exchanges’ system of variation margin. However, when in 1982 non-exchange foreign currency traders asked to come within the ambit of mark-to-market taxation, Congress acceded to their demands even though this market had no equivalent to variation margin. This opportunistic rather than policy-driven history has spawned a great debate amongst tax practitioners as to the scope of the mark-to-market rule governing foreign currency contracts. Several recent cases have added fuel to the debate. The Straddle Shelters of the 1970s Straddle shelters were developed to exploit several structural flaws in the U.S. tax system: (1) the vast gulf between ordinary income tax rate (maximum 70%) and long term capital gain rate (28%), (2) the arbitrary distinction between capital gain and ordinary income, making it relatively easy to convert one to the other, and (3) the non- economic tax treatment of derivative contracts. Straddle shelters were so pervasive that in 1978 it was estimated that more than 75% of the open interest in silver futures were entered into to accommodate tax straddles and demand for U.S. -

Buying Options on Futures Contracts. a Guide to Uses

NATIONAL FUTURES ASSOCIATION Buying Options on Futures Contracts A Guide to Uses and Risks Table of Contents 4 Introduction 6 Part One: The Vocabulary of Options Trading 10 Part Two: The Arithmetic of Option Premiums 10 Intrinsic Value 10 Time Value 12 Part Three: The Mechanics of Buying and Writing Options 12 Commission Charges 13 Leverage 13 The First Step: Calculate the Break-Even Price 15 Factors Affecting the Choice of an Option 18 After You Buy an Option: What Then? 21 Who Writes Options and Why 22 Risk Caution 23 Part Four: A Pre-Investment Checklist 25 NFA Information and Resources Buying Options on Futures Contracts: A Guide to Uses and Risks National Futures Association is a Congressionally authorized self- regulatory organization of the United States futures industry. Its mission is to provide innovative regulatory pro- grams and services that ensure futures industry integrity, protect market par- ticipants and help NFA Members meet their regulatory responsibilities. This booklet has been prepared as a part of NFA’s continuing public educa- tion efforts to provide information about the futures industry to potential investors. Disclaimer: This brochure only discusses the most common type of commodity options traded in the U.S.—options on futures contracts traded on a regulated exchange and exercisable at any time before they expire. If you are considering trading options on the underlying commodity itself or options that can only be exercised at or near their expiration date, ask your broker for more information. 3 Introduction Although futures contracts have been traded on U.S. exchanges since 1865, options on futures contracts were not introduced until 1982. -

Options Strategy Guide for Metals Products As the World’S Largest and Most Diverse Derivatives Marketplace, CME Group Is Where the World Comes to Manage Risk

metals products Options Strategy Guide for Metals Products As the world’s largest and most diverse derivatives marketplace, CME Group is where the world comes to manage risk. CME Group exchanges – CME, CBOT, NYMEX and COMEX – offer the widest range of global benchmark products across all major asset classes, including futures and options based on interest rates, equity indexes, foreign exchange, energy, agricultural commodities, metals, weather and real estate. CME Group brings buyers and sellers together through its CME Globex electronic trading platform and its trading facilities in New York and Chicago. CME Group also operates CME Clearing, one of the largest central counterparty clearing services in the world, which provides clearing and settlement services for exchange-traded contracts, as well as for over-the-counter derivatives transactions through CME ClearPort. These products and services ensure that businesses everywhere can substantially mitigate counterparty credit risk in both listed and over-the-counter derivatives markets. Options Strategy Guide for Metals Products The Metals Risk Management Marketplace Because metals markets are highly responsive to overarching global economic The hypothetical trades that follow look at market position, market objective, and geopolitical influences, they present a unique risk management tool profit/loss potential, deltas and other information associated with the 12 for commercial and institutional firms as well as a unique, exciting and strategies. The trading examples use our Gold, Silver -

Bankruptcy Futures: Hedging Against Credit Card Default

CONSUMER LENDING Bankruptcy Futures: Hedging Against Credit Card Default by Russ Ray his article discusses the new bankruptcy futures contract to be launched by the Chicago Mercantile Exchange and examines the mechanics and contract specifications of this innovation, illus- trating its hedging potential in the process. ometime during the latter half of 1999 or early Credit-card debt is becoming particularly burden- 2000, the Chicago Mercantile Exchange intends some. The average credit-card balance is approximately to launch an innovative new futures contract that $2,500, with typical households having at least three dif- will offer consumer-lending institutions, particularly ferent bank cards. The average card holder also uses six credit-card issuers, a hedge against the bankruptcies additional cards at service stations, department stores, filed by their borrowers. Bankruptcy futures—contracts specialty stores, and other vendors issuing their own cred- to buy or sell a cash-valued index based upon the cur- it cards. rent number of actual bankruptcies—will enable con- Commensurate with such increases in consumer sumer lenders to transfer default risk to other lenders debt is an ever-growing rise in consumer bankruptcies, and/or speculators holding opposite expectations. which, in turn, represent an ever-increasing proportion Significantly, this new contract also constitutes a proxy of total bankruptcies. In 1998, 96.9% of all bankruptcy variable for banks' confidence in the value and liquidity filings were personal—not business—bankruptcies. (In of their own loan portfolios, just as other proxy vari- terms of dollar volume, however, businesses continue to ables now measure consumer and investor confidence. -

Derivative Securities

2. DERIVATIVE SECURITIES Objectives: After reading this chapter, you will 1. Understand the reason for trading options. 2. Know the basic terminology of options. 2.1 Derivative Securities A derivative security is a financial instrument whose value depends upon the value of another asset. The main types of derivatives are futures, forwards, options, and swaps. An example of a derivative security is a convertible bond. Such a bond, at the discretion of the bondholder, may be converted into a fixed number of shares of the stock of the issuing corporation. The value of a convertible bond depends upon the value of the underlying stock, and thus, it is a derivative security. An investor would like to buy such a bond because he can make money if the stock market rises. The stock price, and hence the bond value, will rise. If the stock market falls, he can still make money by earning interest on the convertible bond. Another derivative security is a forward contract. Suppose you have decided to buy an ounce of gold for investment purposes. The price of gold for immediate delivery is, say, $345 an ounce. You would like to hold this gold for a year and then sell it at the prevailing rates. One possibility is to pay $345 to a seller and get immediate physical possession of the gold, hold it for a year, and then sell it. If the price of gold a year from now is $370 an ounce, you have clearly made a profit of $25. That is not the only way to invest in gold. -

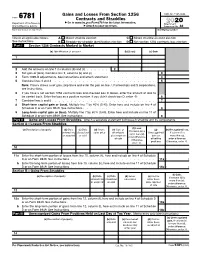

Form 6781 Contracts and Straddles ▶ Go to for the Latest Information

Gains and Losses From Section 1256 OMB No. 1545-0644 Form 6781 Contracts and Straddles ▶ Go to www.irs.gov/Form6781 for the latest information. 2020 Department of the Treasury Attachment Internal Revenue Service ▶ Attach to your tax return. Sequence No. 82 Name(s) shown on tax return Identifying number Check all applicable boxes. A Mixed straddle election C Mixed straddle account election See instructions. B Straddle-by-straddle identification election D Net section 1256 contracts loss election Part I Section 1256 Contracts Marked to Market (a) Identification of account (b) (Loss) (c) Gain 1 2 Add the amounts on line 1 in columns (b) and (c) . 2 ( ) 3 Net gain or (loss). Combine line 2, columns (b) and (c) . 3 4 Form 1099-B adjustments. See instructions and attach statement . 4 5 Combine lines 3 and 4 . 5 Note: If line 5 shows a net gain, skip line 6 and enter the gain on line 7. Partnerships and S corporations, see instructions. 6 If you have a net section 1256 contracts loss and checked box D above, enter the amount of loss to be carried back. Enter the loss as a positive number. If you didn’t check box D, enter -0- . 6 7 Combine lines 5 and 6 . 7 8 Short-term capital gain or (loss). Multiply line 7 by 40% (0.40). Enter here and include on line 4 of Schedule D or on Form 8949. See instructions . 8 9 Long-term capital gain or (loss). Multiply line 7 by 60% (0.60). Enter here and include on line 11 of Schedule D or on Form 8949. -

Futures Options: Universe of Potential Profit

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Directory of Open Access Journals Annals of the „Constantin Brâncuşi” University of Târgu Jiu, Economy Series, Issue 2/2013 FUTURES OPTIONS: UNIVERSE OF POTENTIAL PROFIT Teselios Delia PhD Lecturer, “Constantin Brancoveanu” University of Pitesti, Romania [email protected] Abstract A approaching options on futures contracts in the present paper is argued, on one hand, by the great number of their directions for use (in financial speculation, in managing and risk control, etc.) and, on the other hand, by the fact that in Romania, nowadays, futures contracts and options represent the main categories of traded financial instruments. Because futures contract, as an underlying asset for options, it is often more liquid and involves more reduced transaction costs than cash product which corresponds to that futures contract, this paper presents a number of information regarding options on futures contracts, which offer a wide range of investment opportunities, being used to protect against adverse price moves in commodity, interest rate, foreign exchange and equity markets. There are presented two assessment models of these contracts, namely: an expansion of the Black_Scholes model published in 1976 by Fischer Black and the binomial model used especially for its flexibility. Likewise, there are presented a series of operations that can be performed using futures options and also arguments in favor of using these types of options. Key words: futures options, futures contracts, binomial model, straddle, strangle JEL Classification: G10, G13, C02. Introduction Economies and investments play a particularly important role both at macroeconomic level and at the level of each person or company. -

An Introduction to the VIX Index and Volatility Instruments Alexander Ryvkin Pace University

Pace University DigitalCommons@Pace Honors College Theses Pforzheimer Honors College 2019 Volatility Products and their Uses: An Introduction to the VIX Index and Volatility Instruments Alexander Ryvkin Pace University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/honorscollege_theses Part of the Business Commons Recommended Citation Ryvkin, Alexander, "Volatility Products and their Uses: An Introduction to the VIX Index and Volatility Instruments" (2019). Honors College Theses. 230. https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/honorscollege_theses/230 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pforzheimer Honors College at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Volatility Products and Their Uses 1 Volatility Products and their Uses An Introduction to the VIX Index and Volatility Instruments Pace University, Lubin School of Business Pforzheimer Honors College Majoring in Finance Presenting May 9th, 2019 Graduating May 18th, 2019 Examiner: Andrew Coggins By Alexander Ryvkin Volatility Products and Their Uses 2 Volatility Products and Their Uses 3 Abstract Volatility instruments are complex investment products that can be used to hedge or speculate based on changes in market sentiment and fluctuations in the S&P 500. These products offer a unique approach to protecting one’s portfolio and making strategic bets on future market volatility. However, lack of understanding of these products can be potentially dangerous as they can change dramatically in value within extremely short time-frames. Investors must be wary of using these products improperly; failure to adequately assess the risk of using volatility products can deliver devastating losses to one’s portfolio. -

Financial Derivatives Classification of Derivatives

FINANCIAL DERIVATIVES A derivative is a financial instrument or contract that derives its value from an underlying asset. The buyer agrees to purchase the asset on a specific date at a specific price. Derivatives are often used for commodities, such as oil, gasoline, or gold. Another asset class is currencies, often the U.S. dollar. There are derivatives based on stocks or bonds. The most common underlying assets include stocks, bonds, commodities, currencies, interest rates and market indexes. The contract's seller doesn't have to own the underlying asset. He can fulfill the contract by giving the buyer enough money to buy the asset at the prevailing price. He can also give the buyer another derivative contract that offsets the value of the first. This makes derivatives much easier to trade than the asset itself. According to the Securities Contract Regulation Act, 1956 the term ‘Derivative’ includes: i. a security derived from a debt instrument, share, loan, whether secured or unsecured, risk instrument or contract for differences or any other form of security. ii. a contract which derives its value from the prices or index of prices, of underlying securities. CLASSIFICATION OF DERIVATIVES Derivatives can be classified into broad categories depending upon the type of underlying asset, the nature of derivative contract or the trading of derivative contract. 1. Commodity derivative and Financial derivative In commodity derivatives, the underlying asset is a commodity, such as cotton, gold, copper, wheat, or spices. Commodity derivatives were originally designed to protect farmers from the risk of under- or overproduction of crops. Commodity derivatives are investment tools that allow investors to profit from certain commodities without possessing them. -

China After the Subprime Crisis

China After the Subprime Crisis 9780230_281967_01_prexviii.indd i 9/1/2010 3:41:25 PM Also by Chi Lo: ASIA AND THE SUBPRIME CRISIS: Lifting the Veil on the Financial Tsunami UNDERSTANDING CHINA’S GROWTH: Forces that Drive China’s Economic Future PHANTOM OF THE CHINA ECONOMIC THREAT: Shadow of the Next Asian Crisis THE MISUNDERSTOOD CHINA: Uncovering the Truth behind the Bamboo Curtain WHEN ASIA MEETS CHINA IN THE NEW MILLENNIUM: China’s Role in Shaping Asia’s Post-Crisis Economic Transformation 9780230_281967_01_prexviii.indd ii 9/1/2010 3:41:25 PM China After the Subprime Crisis Opportunities in the New Economic Landscape Chi Lo Chief Economist and Strategist for a Major Investment Management Company based in Hong Kong, China 9780230_281967_01_prexviii.indd iii 9/1/2010 3:41:25 PM © Chi Lo 2010 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6-10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2010 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Palgrave Macmillan in the UK is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. -

Morningstar Global Fixed Income Classification Methodology

? Morningstar Global Fixed Income Classification Morningstar Research Introduction Effective Oct. 31, 2016 Fixed-Income Sectors Contents The fixed-income securities and fixed-income derivative exposures within a portfolio are mapped into 1 Introduction Secondary Sectors that represent the most granular level of classification. Each item can also be 2 Super Sectors 10 Sectors grouped into one of several higher-level Primary Sectors, which ultimately roll up to five fixed-income Super Sectors. Important Disclosure The conduct of Morningstar’s analysts is governed Cash Sectors by Code of Ethics/Code of Conduct Policy, Personal Cash securities and cash-derivative exposures within a portfolio are mapped into Secondary Sectors that Security Trading Policy (or an equivalent of), and Investment Research Policy. For information represent the most granular level of classification. Each item can also be grouped into cash & regarding conflicts of interest, please visit: http://global.morningstar.com/equitydisclosures equivalents Primary Sector and into cash & equivalents Super Sector (cash & equivalents Primary Sector = cash & equivalents Super Sector ). Morningstar includes cash within fixed-income sectors. Cash is not a bond, but it is a type of fixed- income. When bond-fund managers are feeling nervous about interest rates rising, they might increase their cash stake to shorten the portfolio’s duration. Moving assets into cash is a defensive strategy for interest-rate risk. In addition, Morningstar includes securities that mature in less than 92 days in the definition of cash. The cash & equivalents Secondary Sectors allow for more-detailed identification of cash, allowing clients to see, for example, if the cash holdings are in currency or short-term government bonds. -

Order Execution and Placement Policy

Order Execution and Placement Policy Version Effective Date 1.2 30 April 2019 Contents Section 1. Introduction ............................................................................................. 3 1.1 Purpose ................................................................................................................................... 3 1.2 Scope ....................................................................................................................................... 3 1.3 Specific client instructions ..................................................................................................... 4 1.4 Restricted counterparty requirements ................................................................................ 4 1.5 Trading outside a trading venue .......................................................................................... 4 1.6 Delegated portfolio management and execution .............................................................. 4 Section 2. Best Execution ......................................................................................... 6 Section 3. Execution Factor Evaluation ................................................................... 8 Section 4. The Execution Process ........................................................................... 10 4.1 Execution venues and trading venues ............................................................................... 10 4.2 Agency or principal .............................................................................................................