OCHPANIZTLI and CLASSICAL NAHUATL SYLLABLE Strucl'ure 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

6 X 10.5 Long Title.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-51840-6 - An Introduction to Classical Nahuatl Michel Launey Excerpt More information Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī PART Ī Ī ONE Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-51840-6 - An Introduction to Classical Nahuatl Michel Launey Excerpt More information PRELIMINARY LESSON Phonetics and Writing S ince the time of the conquest, Nahuatl has been written by means of theLatinalphabet.Thereis,therefore,alongtraditiontowhichitis preferable to conform for the most part. Nonetheless, for the following reasons, somewordsinthisbookarewritteninanorthographythatdiffersfromthe traditional one. ̈ Theorthographyis,ofcourse,“hispanicized.”Torepresentthephoneticele- ments of Nahuatl, the letters or combinations of letters that represent identical or similar sounds in Spanish are used. Hence, there is no problem with the sounds that exist in both languages, not to mention those that are lacking in Nahuatl (b, d, g, r etc.). On the other hand, those that exist in Nahuatl but not inSpanisharefoundinalternatespellings,orareevenaltogetherignored.In particular, this is the case with vowel length and (even worse) with the glottal stop (see Table 1.1), which are systematically marked only by two grammar- ians, Horacio Carochi and Aldama y Guevara, and in a text named Bancroft Dialogues.1 ̈ This defective character is heightened by a certain fluctuation because the orthography of Nahuatl has never really been fixed. Hence, certain texts represent the vowel /i/ indifferently with i or j, others always represent it with i but extend this spelling to consonantal /y/, that is, to a differ- ent phoneme. -

Saltillo Street Names Index: Autumn Gleen Dr

M R - 6 - E R R - 5 - E C c 1 2 3 D 4 5 6 7 U C S D A T R . E R D L 6 . 8 E 3 Y SNER ST. RD 2446 MES SALTILLO STREET NAMES INDEX: AUTUMN GLEEN DR. E3 OLD HWY. 51 E3 A BAUHAUS DR. E3 OLD NATCHEZ TRACE TRAIL G3 BENT GRASS CIR. H2 OLD SALTILLO RD. E4, F4, F5, G5, H4, H5 A BERCH TREE DR. F4 OLD SOUTH PLANTATION DR. E2 R D BIG HARPE TRAIL G2 OLIVIA CV. D4 BIRMINGHAM RIDGE RD. F1, F2, G3 7 PARKRIDGE DR, F4 8 3 BOLIVAR CIR. G3 PATTERSON CIR. E5 . D BOSTIC AVE. E4 PECAN DR. D5 R BRIDLE CV. E3 PETE AVE. F3 D U BRISCOE ST. E4 PEYTON LN. D4 H BROCK DR. F3 33 35 35 35 PINECREST ST. E4 ST 32 32 33 TOWERY . CARTWRIGHT AVE. E4 PINEHURST AVE. E4 31 36 31 R 4 3 D 3 2 CHAMPIONS CV. H2 PINEWOOD ST. E4 5 6 5 4 CHERRY HILL DR. C4 POPULARWOOD LN. F4 1 6 9 5 CHESTNUT LN. C4 PRINSTON DR. E3 1 CHICKASAW CIR. G3 PULLTIGHT RD. B4, C4 CHICKASAW TRAIL G3 PYLE DR. E4 CHRISTY WAY C4 QUAIL CREEK RD. E3 CO 653-B H2, H3 RAILROAD AVE. E5 CO 653-D G3 RD 189 F3 CO 2012 E2, E3 RD 251 D2 3 CO 2012 F3 8 RD 521 C1, E2 7 CO 2720 A1 RD 599 C1, C2, D2 D R CO 2720 B1 RD 647 H3 COBBS CV. -

Toward a Comprehensive Model For

Toward a Comprehensive Model for Nahuatl Language Research and Revitalization JUSTYNA OLKO,a JOHN SULLIVANa, b, c University of Warsaw;a Instituto de Docencia e Investigación Etnológica de Zacatecas;b Universidad Autonóma de Zacatecasc 1 Introduction Nahuatl, a Uto-Aztecan language, enjoyed great political and cultural importance in the pre-Hispanic and colonial world over a long stretch of time and has survived to the present day.1 With an estimated 1.376 million speakers currently inhabiting several regions of Mexico,2 it would not seem to be in danger of extinction, but in fact it is. Formerly the language of the Aztec empire and a lingua franca across Mesoamerica, after the Spanish conquest Nahuatl thrived in the new colonial contexts and was widely used for administrative and religious purposes across New Spain, including areas where other native languages prevailed. Although the colonial language policy and prolonged Hispanicization are often blamed today as the main cause of language shift and the gradual displacement of Nahuatl, legal steps reinforced its importance in Spanish Mesoamerica; these include the decision by the king Philip II in 1570 to make Nahuatl the linguistic medium for religious conversion and for the training of ecclesiastics working with the native people in different regions. Members of the nobility belonging to other ethnic groups, as well as numerous non-elite figures of different backgrounds, including Spaniards, and especially friars and priests, used spoken and written Nahuatl to facilitate communication in different aspects of colonial life and religious instruction (Yannanakis 2012:669-670; Nesvig 2012:739-758; Schwaller 2012:678-687). -

Configurationality in Classical Nahuatl*

Configurationality in Classical Nahuatl* Jason D. Haugen Oberlin College Abstract: Some classic generativist analyses (Jelinek 1984, Baker 1996) predict that polysynthetic languages should be non-configurational by positing that the arguments of verbs are marked by clitics or affixes and relegating overt NPs/DPs to adjunct positions. Here I argue that the polysynthetic Uto-Aztecan language Classical Nahuatl (CN) was actually configurational. I claim that unmarked VSO order was derived by verb phrase (vP) fronting, from a base-generated structure of SVO. A vP constituent is evidenced by obligatory movement of indefinite object NPs with the vP, as in pseudo noun incorporation analyses given for VOS order in other predicate-initial languages such as Niuean (Polynesian) (Massam 2001) and Chol (Mayan) (Coon 2010). The CN case is interesting to contrast with languages like Chol, which lack head movement, in that the CN word order facts show the hallmarks of vP remnant movement (i.e., the fronting of the verb plus its determinerless NP object into a position structurally higher than the subject), while the actual morphology of the CN verb shows the hallmarks of head movement (including noun incorporation, tense/aspect/mood suffixes, derivational suffixes such as the applicative and causative, and pronominal agreement prefixes marked on the verb). Finally, in regard to the landing site for the fronted predicate, I argue that the placement of CN’s optional clause-introducing particle ca necessitates adopting the split-Comp proposal of Rizzi (1997), as is suggested for Welsh by Roberts (2005). Specifically, I claim for CN that ca is the head of ForceP and that the predicate fronts to a position in the structurally lower Fin(ite)P. -

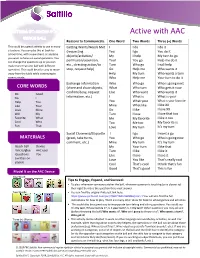

Active with AAC

Active with AAC Reasons to Communicate One Word Two Words Three (+) Words This could be a great activity to use in many Getting Wants/Needs Met I I do I do it situations. You can play this at back-to- (requesting You I go You do it school time, with a new client, or anytime objects/activities/ My I help My turn to go you want to focus on social questions. You can change the questions up or you can permission/attention, Your You go Help me do it make more than one ball with different etc., directing action/to Turn Who go I will help stop, request help) Go Help me Who wants it questions. This could be a fun way to move away from the table while continuing to Help My turn Who wants a turn communicate. Who Help me Your turn to do it Exchange Information Who Who go Who is going next CORE WORDS (share and show objects, What Who turn Who gets it now confirm/deny, request Like Who want Who wants it Do Good Go I information, etc.) I What is What is your Help You You What your What is your favorite Like Your Mine What like I like XX Love Mine Go I like I love XX Will My Turn I love I love that too Favorite What Me My favorite I like it too Cool Who Too Me too My favorite is Fun That Love My turn It’s my turn Social Closeness/Etiquette I I go I want a go MATERIALS (greet, take turns, You Who go Who is going now comment, etc.) Mine My turn It’s my turn Beach ball Device My Your turn I like that Velcro/glue AAC user Turn I like I like it Questions You Like I love I love it (written on Love You like That’s really cool paper) Cool That’s cool I think that’s fun Good That’s good This is fun Model It on the AAC Device One Word: Tips to Engage, Expand, and Succeed: • To play: whenever someone catches the ball, whatever question is touching (or is closest to) their right thumb is the question they must answer. -

Uto-Aztecan Maize Agriculture: a Linguistic Puzzle from Southern California

Uto-Aztecan Maize Agriculture: A Linguistic Puzzle from Southern California Jane H. Hill, William L. Merrill Anthropological Linguistics, Volume 59, Number 1, Spring 2017, pp. 1-23 (Article) Published by University of Nebraska Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/anl.2017.0000 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/683122 Access provided by Smithsonian Institution (9 Nov 2018 13:38 GMT) Uto-Aztecan Maize Agriculture: A Linguistic Puzzle from Southern California JANE H. HILL University of Arizona WILLIAM L. MERRILL Smithsonian Institution Abstract. The hypothesis that the members of the Proto—Uto-Aztecan speech community were maize farmers is premised in part on the assumption that a Proto—Uto-Aztecan etymon for ‘maize’ can be reconstructed; this implies that cognates with maize-related meanings should be attested in languages in both the Northern and Southern branches of the language family. A Proto—Southern Uto-Aztecan etymon for ‘maize’ is reconstructible, but the only potential cog- nate for these terms documented in a Northern Uto-Aztecan language is a single Gabrielino word. However, this word cannot be identified definitively as cognate with the Southern Uto-Aztecan terms for ‘maize’; consequently, the existence of a Proto—Uto-Aztecan word for ‘maize’ cannot be postulated. 1. Introduction. Speakers of Uto-Aztecan languages lived across much of western North America at the time of their earliest encounters with Europeans or Euro-Americans. Their communities were distributed from the Columbia River drainage in the north through the Great Basin, southern California, the American Southwest, and most of Mexico, with outliers as far south as Panama (Miller 1983; Campbell 1997:133—38; Caballero 2011; Shaul 2014). -

Phonetics and Phonology

46 2 Phonetics and Phonology In this chapter I describe the segmental and suprasegmental categories of CLZ phonology, both how they are articulated and how they fall into the structures of syllable and word. I also deal with phono-syntactic and phono-semantic issues like intonation and the various categories of onomatopoetic words that are found. Other than these last two issues this chapter deals only with strictly phonetic and phonological issues. Interesting morpho-phonological details, such as the details of tonal morphology, are found in Chapters 4-6. Sound files for most examples are included with the CD. I begin in §2.1 and §2.2 by describing the segments of CLZ, how they are articulated and what environments they occur in. I describe patterns of syllable structure in §2.3. In §2.4 I describe the vowel nasalization that occurs in the SMaC dialect. I go on to describe the five tonal categories of CLZ and the main phonetic components of tone: pitch, glottalization and length in §2.5. Next I give brief discussions of stress (§2.6), and intonation (§2.7). During the description of segmental distribution I often mention that certain segments have a restricted distribution and do not occur in some position except in loanwords and onomatopoetic words. Much of what I consider interesting about loanwords has to do with stress and is described in §2.6 but I also give an overview of loanword phonology in §2.8. Onomatopoetic words are sometimes outside the bounds of normal CLZ phonology both because they can employ CLZ sounds in unusual environments and because they may contain sounds which are not phonemic in CLZ. -

What Are Core Words Anyway? Let Us Help You Get Started! Part 1 Goals for AAC Users

What Are Core Words Anyway? Let Us Help You Get Started! Part 1 Introductions and Presentation Goals Goals for AAC Users a. Learn cause and effect Reasons why we communicate b. Communicate with peers 1) Naming and adults c. Learn Language 2) Greeting d. Initiate – not just respond 3) Commenting e. Make friends 4) Requesting Objects f. Social skills g. Learn educational content 5) Protesting h. Participate in class or 6) Requesting Information workplace 7) Responding i. Gain independence – say 8) Requesting Action what they want to say! 9) Responding to Request 10) Regulating Conversational Behavior 11) Relaying Past Events Commenting 12) Stating Greeting Naming Activity to Build Communication Responding Requesting Objects Protesting Requesting Information Requesting Action Making a Snack Reading a Book Suggested Activity https://saltillo.com/ 1 © 2020 PRC-Saltillo. Non-commercial reprint rights for clinical or personal use granted with inclusion of copyright notice. Commercial use prohibited; may not be used for resale. Contact PRC-Saltillo for questions regarding permissible uses. Understand the target Various ways to look at language development, but ultimately they lead us down the same path • Developmental Milestones • Language acquisition stages • Browns Stages How can we aim for the target? Use CORE VOCABULARY! Notes Core vocabulary is: o Reusable across contexts, o Made up of approximately 250-400 words that account for 80% of our utterances, and is the same across gender, age, topic, setting, and disability. o Includes pronouns, verbs, adjectives, questions, interjections, prepositions and adverbs. Which class of words is missing? ______________ https://saltillo.com/ 2 © 2020 PRC-Saltillo. Non-commercial reprint rights for clinical or personal use granted with inclusion of copyright notice. -

AAC Basics and Implementation: How to Teach Students Who “Talk with Technology”

AAC Basics and Implementation: How to Teach Students who “Talk with Technology” Paul Visvader MA CCC-SLP Assistive Technology Team, Boulder Valley School District, Boulder, CO ©2013 AAC Basics and Implementation: How to Teach Students who “Talk with Technology” “Augmentative or Alternative Communication (AAC) is any device, system, or method that improves the ability of a child with a communication impairment to communicate effectively.” Paul Visvader MA CCC-SLP © 2013 Assistive Technology Team, Boulder Valley School District, Boulder, CO Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Background ...................................................................................................................................... 4 Learning communication skills .................................................................................................. 4 Three levels of communicative abilities .................................................................................... 5 Augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) .............................................................. 5 AAC Evaluation ................................................................................................................................. 7 The “AAC Toolbox” (a general discussion) ....................................................................................... 8 AAC Setup and Implementation ................................................................................................... -

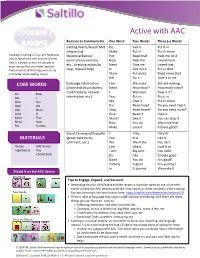

Active with AAC

Active with AAC Reasons to Communicate One Word Two Words Three (+) Words Getting Wants/Needs Met Want I want I want that one Many children love to play board games! (requesting Need You need I need it But, you may be wondering what can I model and say while playing a board objects/activities/ That Put there Put it there game? There are plenty of core words you permission/attention, There Put on Put it on there can model while playing any board game etc., directing action/to Put Give that Give me that one you want! Check out the chart and our Tips stop, request help) Give Want that Help me open it to Engage, Expand, and Succeed! Help Help open Let’s play again Open Go + “color” Go to “color” Exchange Information Open Put on? I did it CORE WORDS (share and show objects, Like I do/did Put it there confirm/deny, request That You put Put in on here? Do I Give You information, etc.) There Need that I need that Go My Put What next? You need this one? Like Uh-oh On You win Open that one Lose Cool In I lose Let’s play more Need There Let’s Where put? I go next Put That Where Open that What is next? Want “Colors” What Let’s play I lose again Win Again Next I go I go again Social Closeness/Etiquette I My turn I did it MATERIALS (greet, take turns, You I go I go again comment, etc.) My You go Uh-oh! You lose Board Game You Turn I win Cool! I win! AAC User Go You lose Let’s play again AAC Device Win That cool That is “color” Lose Let’s play That was cool Uh-oh I do It’s my turn Colors That + “color” This is fun Model It on the AAC Device One Word: Tips to Engage, Expand, and Succeed: The most important thing to remember while you play is to keep it natural. -

Active with AAC

Active with AAC Reasons to Communicate One Word Two Words Three (+) Words Getting Wants/Needs Met Do Get it Put it in (requesting Make Put in Put in more Cooking, or baking, is a fun and functional objects/activities/ Put Need that Help me do it way to spend time with your child/client. permission/attention, Help Help me I need more And as a bonus, at the end, you get to enjoy eating what you made together! etc., directing action/to Need Give me I need that stop, request help) In Get more Put in that Take a look at all the things you can say and model while cooking. Enjoy! More Put more Need more that Get Do it Give it to me Exchange Information Like We make We are making CORE WORDS (share and show objects, Need How much? How much need? confirm/deny, request I We need How is it? Do Stop Get I information, etc.) You Put in Put it in Give You We Give it Put in more Help We Put Need help? Do you need help? Like More Stop Need more? Do you need more? Look In Give Need it I like it Make That More? Like it You can stop it Need How How You do We make that Put Yummy Make Look it It looks good! Social Closeness/Etiquette I I like I like it! MATERIALS (greet, take turns, You It in I do it comment, etc.) We We make You do it Recipe AAC Device Like Like it I put it in Ingredients You Turn My turn You did it Child/Client Do I do It looks good Good You do It is good! Yummy It good It is yummy! In It yummy We make it Model It on the AAC Device One Word: Tips to Engage, Expand, and Succeed: • Depending on your child/client and the recipe, it might be safest to use a low-tech board to keep the AAC device protected from liquids or other accidents while cooking. -

User's Guide for Dedicated Model

User’s Guide for Dedicated Model Saltillo Corporation 2143 Township Road 112 Millersburg, OH 44654 www.saltillo.com NOVA chat and VocabPC are trademarks of Saltillo Corporation. Microsoft and Windows are either registered trademarks or trademarks of Microsoft Corporation in the United States and/or other countries. Android is a trademark of Google Inc. Samsung and Galaxy Tab are registered trademarks of Samsung Electronics America, Inc. Android Market is a trademark of Google Inc. Neospeech is a trademark of Neospeech Inc. Loquendo is a trademark of Loquendo S.p.A. Ivona is Copyright © 2001-2010, IVO Software Sp.z o.o. Acapela is a trademark of Acapela Group PCS Symbols illustrations are copyright of Mayer-Johnson Co. Symbol Stix is copyright of News2You. "The Library of Character/Logo Symbols contained in this software is included free of charge, may be used solely for communication purposes and may not be sold, copied or otherwise exploited for any type of profit." WordPower and ChatPower is copyright of Inman Innovations My QuickChat 12 Adult is copyright of Talk To Me Technologies My QuickChat 12 Child is copyright of Talk To Me Technologies My QuickChat 8 Adult is copyright of Talk To Me Technologies My QuickChat 8 Child is copyright of Talk To Me Technologies My QuickChat 4 Child is copyright of Talk To Me Technologies NOVA chat Editor CD NOVA chat Editor, owned by Saltillo Corporation Microsoft Voices, owned by Microsoft Corporation Microsoft's agreement states: INSTALLATION AND USE RIGHTS. You may install and use one copy of the software on each computer on your premises that you use to exchange data and software with portable devices powered by a Microsoft operating system.