City of South Bend 2020-2040 Comprehensive Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pacific County, Washington and Incorporated Areas

PACIFIC COUNTY, WASHINGTON AND INCORPORATED AREAS COMMUNITY NAME COMMUNITY NUMBER ILWACO, TOWN OF 530127 LONG BEACH, TOWN OF 530128 PACIFIC COUNTY, 530126 UNINCORPORATED AREAS RAYMOND, CITY OF 530129 SHOALWATER BAY INDIAN TRIBE 530341 SOUTH BEND, CITY OF 530130 Pacific County PRELIMINARY: AUGUST 30, 2013 FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY NUMBER 53049CV000A NOTICE TO FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY USERS Communities participating in the National Flood Insurance Program have established repositories of flood hazard data for floodplain management and flood insurance purposes. This Flood Insurance Study (FIS) report may not contain all data available within the Community Map Repository. Please contact the Community Map Repository for any additional data. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) may revise and republish part or all of this FIS report at any time. In addition, FEMA may revise part of this FIS report by the Letter of Map Revision process, which does not involve republication or redistribution of the FIS report. Therefore, users should consult with community officials and check the Community Map Repository to obtain the most current FIS report components. Selected Flood Insurance Rate Map (FIRM) panels for this community contain information that was previously shown separately on the corresponding Flood Boundary and Floodway Map (FBFM) panels (e.g., floodways, cross sections). In addition, former flood hazard zone designations have been changed as follows: Old Zone(s) New Zone Al through A30 AE B X C X Initial Countywide FIS Effective Date: To Be Determined TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Purpose of Study ................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Authority and Acknowledgments ...................................................................... 1 1.3 Coordination ..................................................................................................... -

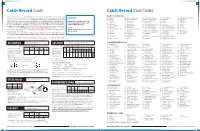

Catch Record Cards & Codes

Catch Record Cards Catch Record Card Codes The Catch Record Card is an important management tool for estimating the recreational catch of PUGET SOUND REGION sturgeon, steelhead, salmon, halibut, and Puget Sound Dungeness crab. A catch record card must be REMINDER! 824 Baker River 724 Dakota Creek (Whatcom Co.) 770 McAllister Creek (Thurston Co.) 814 Salt Creek (Clallam Co.) 874 Stillaguamish River, South Fork in your possession to fish for these species. Washington Administrative Code (WAC 220-56-175, WAC 825 Baker Lake 726 Deep Creek (Clallam Co.) 778 Minter Creek (Pierce/Kitsap Co.) 816 Samish River 832 Suiattle River 220-69-236) requires all kept sturgeon, steelhead, salmon, halibut, and Puget Sound Dungeness Return your Catch Record Cards 784 Berry Creek 728 Deschutes River 782 Morse Creek (Clallam Co.) 828 Sauk River 854 Sultan River crab to be recorded on your Catch Record Card, and requires all anglers to return their fish Catch by the date printed on the card 812 Big Quilcene River 732 Dewatto River 786 Nisqually River 818 Sekiu River 878 Tahuya River Record Card by April 30, or for Dungeness crab by the date indicated on the card, even if nothing “With or Without Catch” 748 Big Soos Creek 734 Dosewallips River 794 Nooksack River (below North Fork) 830 Skagit River 856 Tokul Creek is caught or you did not fish. Please use the instruction sheet issued with your card. Please return 708 Burley Creek (Kitsap Co.) 736 Duckabush River 790 Nooksack River, North Fork 834 Skokomish River (Mason Co.) 858 Tolt River Catch Record Cards to: WDFW CRC Unit, PO Box 43142, Olympia WA 98504-3142. -

Shoreline Analysis Report

PACIFIC COUNTY Grant No. G1400525 Shoreline Analysis Report for Shorelines in Pacific County Prepared for: Pacific County 1216 W. Robert Bush Drive PO Box 68 South Bend, WA 98586 Prepared by: STRATEGY | ANALYSIS | COMMUNICATIONS 2025 First Avenue, Suite 800 Seattle WA 98121 110 Main St # 103 Edmonds, WA 98020 Drafted June 2014, Public Draft September 2014, Revised January 2015, This report was funded in part Final June 2015 through a grant from the Washington Department of Ecology. The Watershed Company Reference Number: 130727 Cite this document as: The Watershed Company, BERK, and Coast and Harbor Engineering. June 2015. Shoreline Analysis Report for Shorelines in Pacific County. Prepared for Pacific County, South Bend, WA. Acknowledgements The consultant team wishes to thank the Pacific County Shoreline Planning Committee, who contributed significant comments and materials toward the development of this report. The Watershed Company June 2015 T ABLE OF C ONTENTS Page # Readers Guide .................................................................................. i 1 Introduction ................................................................................ 1 1.1 Background and Purpose ............................................................................. 1 1.2 Shoreline Jurisdiction ................................................................................... 1 1.3 Study Area ..................................................................................................... 4 2 Summary of Current Regulatory Framework -

Willapa National Wildlife Refuge

Willapa National Wildlife Refuge Comprehensive Conservation Plan Amendment and Environmental Assessment for the Proposed Natural Resource Center Prepared by: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Willapa National Wildlife Refuge Complex 3888 SR 101 Ilwaco, Washington 98624 September 2017 Acronyms/Abbreviations Acronym Full Phrase ADA Americans With Disabilities Act BMP Best Management Practice BTU British Thermal Unit CCP Comprehensive Conservation Plan CERCLA Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act CEQ Council on Environmental Quality CFR Code of Federal Regulations CO2 Carbon dioxide dBA Decibels DM Departmental Manual EA Environmental Assessment EDNA Environmental Designation for Noise Abatement EIS Environmental Impact Statement EO Executive Order ESA Endangered Species Act EUI Energy Use Intensity FEMA Federal Emergency Management Agency FHWA Federal Highway Administration FIRM Flood Insurance Rate Map FLAP Federal Lands Access Program FONSI Finding of No Significant Impact FR Federal Register ft2 Square foot, square feet GHG Greenhouse gas 1 kBTU/ft2/yr Thousands of British Thermal Units per square foot per year LEED Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design NEPA National Environmental Policy Act NHPA National Historic Preservation Act NO2 Nitrogen dioxide NOx Nitrogen oxides NRCS Natural Resource Conservation Service NWR National Wildlife Refuge NWI National Wetlands Inventory O3 Ozone PCEMA Pacific County Emergency Management Agency PEM Palustrine emergent PFO Palustrine forested PM2.5 Particulate matter less than 2.5 micrometers PM10 Particulate matter less than 10 micrometers PSS Palustrine scrub-shrub PUBH Palustrine unconsolidated bottom permanently flooded PUD Public Utility District Refuge Willapa National Wildlife Refuge ROD Record of Decision SHPO State Historic Preservation Office SO2 Sulfur dioxide U.S.C. -

Willapa River Fecal Coliform Bacteria Total Maximum Daily Load

Willapa River Fecal Coliform Bacteria Total Maximum Daily Load Water Quality Improvement Report June 2007 Publication No. 07-03-021 Publication Information This report is available on the Department of Ecology’s website at www.ecy.wa.gov/biblio/0703021.html For more information contact: Publications Coordinator Environmental Assessment Program P.O. Box 47600 Olympia, WA 98504-7600 E-mail: [email protected] Phone: (360) 407-6764 Washington State Department of Ecology - www.ecy.wa.gov/ o Headquarters, Lacey 360-407-6000 o Northwest Regional Office, Bellevue 425-649-7000 o Southwest Regional Office, Lacey 360-407-6300 o Central Regional Office, Yakima 509-575-2490 o Eastern Regional Office, Spokane 509-329-3400 Data for this project are available at Ecology’s Environmental Information Management (EIM) website at www.ecy.wa.gov/eim/index.htm. Search User Study ID, OGEO0001. The Study Tracker Code for this study is 07-508. Any use of product or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the author or the Department of Ecology. If you need this publication in an alternate format, call Joan LeTourneau at (360) 407-6764. Persons with hearing loss can call 711 for Washington Relay Service. Persons with a speech disability can call 877-833-6341. Cover photo: Green 35 navigation marker and light, located approximately midway between Potter Slough and the mouth of the Willapa River. Willapa River Fecal Coliform Bacteria Total Maximum Daily Load Water Quality Improvement Report by Anise Ahmed -

Non-Federal Waters

Federal Navigable Waters in Washington State Body of Water and Location Navigable Non-navigable REMARKS Bachelor Island Side channel of Columbia River. Mouth X Slough 14 miles S of Vancouver, WA (tidal). Part of Columbia Estuary. Chinook to Ilwaco Baker Bay X (including West Channel). Bear Creek X At mile 0.8. Flows into Willapa Bay. Navigable to head of Bear River X tidewater, about 4 miles above mouth. (Hood Canal) Navigable to mouth of Big Beef Big Beef Harbor X Creek (tidal). Bingen Channel X Columbia River, Bonneville Pool Backwater. Side channel of Columbia River. 1 mile S of Birnie Slough X Cathlamet on Puget Island (tidal). Bogachiel River X Tributary of Quillayute River. Tributary of Skamokawa Creek. Mouth at Brooks Slough X Skamokawa. Budd Inlet X Puget Sound. Near Olympia. Side channel of Columbia River. Mouth 5 miles Burke Slough X upstream from Kalama (tidal). Southwestern Clark County; originates Mill Burnt Bridge Creek X Plains area, 7 miles to Vancouver Lake. Near Olympia. Formed by dam at mouth of Capitol Lake X Deschutes River. Carr Inlet X Puget Sound. Pierce County. Side channel of Columbia River near Longview Carrol’s Channel X (tidal). Case Inlet X Puget Sound. Mason County. Side channel of Columbia River at Cathlamet Cathlamet Channel X (tidal). Flows into Lake Washington at Renton. Cedar River X Navigable to mile 1.3. Flows into Puget Sound near Steilacoom. See Chambers Creek X Steilacoom Waterway. Charlton Channel X Navigable to mile 4. Chehalis River X Flows into Grays Harbor. Navigable to mile 68. Chelan, Lake X Only outlet is Chelan River. -

Shoreline Analysis Report Describes Existing Conditions and Characterizes Ecological Functions in the Shoreline Jurisdiction

The Watershed Company May 2015 S HORELINE A NALYSIS R EPORT PACIFIC COUNTY 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background and Purpose Pacific County (County) obtained a grant from the Washington Department of Ecology (Ecology) in 2014 to complete a comprehensive update of its Shoreline Master Program (SMP). One of the first steps of the update process is to inventory and characterize the County’s shorelines as defined by the state’s Shoreline Management Act (SMA) of 1971 (RCW 90.58). This analysis was conducted in accordance with the SMP Guidelines (Guidelines, Chapter 173- 26 Washington Administrative Code (WAC)) and project Scope of Work promulgated by Ecology, and includes all unincorporated areas within the County. Under these Guidelines, the County must identify and assemble the most current, applicable, accurate and complete scientific and technical information available. This Shoreline Analysis Report describes existing conditions and characterizes ecological functions in the shoreline jurisdiction. This assessment of current conditions will serve as the baseline against which the impacts of future development actions in shoreline jurisdiction will be measured. The Guidelines require that the County demonstrates that its updated SMP yields “no net loss” in shoreline ecological functions relative to the baseline (current condition). The no net loss requirement is a new standard in the Guidelines that is intended to be used by local jurisdictions to test whether the updated SMP will in fact accomplish the SMA objective of protecting ecological functions. 1.2 Shoreline Jurisdiction As defined by the SMA, shorelines include certain waters of the state plus their associated “shorelands.” At a minimum, the waterbodies designated as shorelines of the state are streams whose mean annual flow is 20 cubic feet per second (cfs) or greater, lakes whose area is greater than 20 acres, and all marine waters extending three miles offshore. -

Evaluate Selective Fishing in the Willapa River, a Pacific Northwest Estuary

STATE OF WASHINGTON July 2007 Evaluate Selective Fishing in the Willapa River, a Pacific Northwest Estuary by C.E. Ashbrook, J.F. Dixon, K. E. Ryding, K.W. Hassel, and E. A. Schwartz WashingtonWashington DepartmentDepartment ofof FISHFISH ANDAND WILDLIFEWILDLIFE FishFish ProgramProgram Science Division FPT 06-06 Evaluate selective fishing in the Willapa River, a Pacific Northwest estuary Final report for Saltonstall Kennedy #NA03NMF4270133 Ashbrook, C.E., J.F. Dixon, K.E. Ryding, K.W. Hassel, and E. A. Schwartz Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife 600 Capitol Way N. Olympia, WA 98501 Email: [email protected] Telephone: (360) 902-2672 Facsimile: (360) 902-2944 July 2007 Abstract Selective fishing is defined as the ability of a fishing operation to avoid non-target species and stocks, or when encountered, to capture and release them in a manner that minimizes mortality. Commercial and sport gears were tested in an estuary environment to selectively harvest adult hatchery coho (Oncorhynchus kisutch) and release natural coho and fall Chinook salmon (O. tshawytscha) bycatch. Experienced commercial fishers fished tangle nets (8.9 cm (3.5”) mesh size, multifilament net) and gill nets (14.6 cm (5.75”) mesh size, monofilament net) suitable for a coho fishery. To minimize mortality as much as possible, fishers also used careful handling techniques, a revival box, a shorter net, and shorter soak times. During the same time period, experienced sport fishers fished using barbless hooks and herring. Live fish were tagged and released for recovery in sport fisheries, commercial fisheries, at hatchery racks, and during spawning ground surveys. Overall, the tangle net performed better for condition at capture and release. -

Comprehensive Park Plan

2016 – 2022 Comprehensive Park Plan March 2016 Comprehensive Park Plan City Council: Lisa Olsen Clarence Williams Patricia Neve Karla Weber Robert Hall Mayor: Julie Struck Staff: Dee Roberts, Clerk/Treasurer Kim Porter, Deputy Clerk/Treasurer Dennis Houk, City Supervisor Project Consultant: John Kliem, Creative Community Solutions, Inc. www.ccsolympia.com Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 1 Goals and Objectives ....................................................................................................................... 3 Encourage sponsorship of city parks by the community ............................................................ 3 Maintenance of existing parks .................................................................................................... 3 Pioneer Park Project ................................................................................................................... 4 Refurbish First Street Park .......................................................................................................... 4 Establish an Off-Leash Dog Park ................................................................................................. 4 Willapa Hills Trail State Park Extension ...................................................................................... 5 More tourist related park conveniences ................................................................................... -

Contents 5.1 INTRODUCTION

SECTION 5 TRANSPORTATION ELEMENT Contents 5.1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................ 1 5.2 RELATIONSHIP OF TRANSPORTATION ELEMENT TO OTHER PLANS ....................................... 1 5.2.1 GROWTH MANAGEMENT ACT ............................................................................................... 1 5.2.2 STATE-WIDE PLANNING GOALS (Washington Transportation Plan 2040) ............................ 2 5.2.3 STATE RESILIENCY RECOMMENDATIONS ............................................................................. 3 5.2.2 COUNTY-WIDE PLANNING POLICIES..................................................................................... 3 5.3 LEVEL OF SERVICE AND CONCURRENCY ................................................................................... 5 5.4 INVENTORY OF THE TRANSPORTATION SYSTEM....................................................................... 5 5.4.1 STATE HIGHWAYS ................................................................................................................. 5 5.4.2 COUNTY ROADS AND FUNCTIONAL CLASSIFICATIONS ......................................................... 6 5.4.3 PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION .................................................................................................... 6 5.4.4 NON-MOTORIZED TRAFFIC FACILITIES AND TRAILS ............................................................. 6 5.4.5 AIR ....................................................................................................................................... -

Population Genetic Analysis of Chehalis River Watershed Winter Steelhead (Oncorhynchus Mykiss)

STATE OF WASHINGTON October 2017 Population Genetic Analysis of Chehalis River Watershed Winter Steelhead (Oncorhynchus mykiss) by Todd R. Seamons, Curt Holt, Sara Ashcraft, and Mara Zimmerman Washington Department of FISH AND WILDLIFE Fish Program Fish Science Division FPT 17-14 Population genetic analysis of Chehalis River watershed winter steelhead (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Todd R. Seamons1, Curt Holt2, Sara Ashcraft2, and Mara Zimmerman1 13 October, 2017 Author information 1Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, 600 Capitol Way N., Olympia, WA 98501 2Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife Region 6, 48 Devonshire Road, Montesano, WA 98563 Acknowledgements We appreciate the efforts of field crews who collected the samples and Todd Kassler and Cherril Bowman in the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife Molecular Genetics Laboratory for their diligence in managing contracts and producing data (respectively). We are grateful for permission from USFWS Abernathy Tech Center and from the Quinault Tribe to use Abernathy Creek and Olympic Peninsula rivers collections for baseline data. This work was funded by the Washington State Legislature in Second Engrossed House Bill 1115 (Chapter 3, Laws of 2015) designated for study, analysis, and implementation of flood control projects in the Chehalis River Basin. Projects under this funding were selected to fill key information gaps identified in the Aquatic Species Enhancement Plan Data Gaps Report published in August 2014. Project funding was administered by the Washington State Recreation Conservation Office. Recommended citation: Seamons, T., C. Holt, S. Ashcraft, and M. Zimmerman. 2017. Population genetic analysis of Chehalis River Watershed Winter Steelhead (Oncorhynchus mykiss), FPT 17-14. Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, Olympia, Washington. -

Pacific County (Wria 24) Strategic Plan for Salmon Recovery

PACIFIC COUNTY (WRIA 24) STRATEGIC PLAN FOR SALMON RECOVERY CHUM SALMON (Oncorhynchus keta) June 29, 2001 Prepared for: Pacific County P.O. Box 68 South Bend, WA 98586 Prepared by : Applied Environmental Services, Inc 1550 Woodridge Dr. SE Port Orchard, WA 98366 TTABLEABLE OOFF CCONTENTSONTENTS PPageage i CHAPTER PAGE 1.0 Executive Summary 1 1.1 The Pacific County (WRIA 24) Strategic Plan for Salmon Recovery 1 2.0 Introduction 2 2.1 Historical Perspectives and Conditions 2 2.2 Ecosystem Conditions 2 2.3 Future Priorities 3 3.0 Mission Statement, Strategy, Guiding Principles and Key Issues 5 3.1 Willapa Bay Water Resources Coordinating Council Mission Statement 5 3.2 Willapa Bay Water Resources Coordinating Council Mission Strategy 5 3.3 Willapa Bay Water Resources Coordinating Council Guiding Principles 5 4.0 WRIA 24 Watershed Characteristics 8 4.1 Introduction 8 4.2 Data Sources 8 4.3 Critical Elements of Salmon Habitat 9 4.3.1 Spawning and Rearing Habitat 9 4.3.2 Floodplain Conditions 10 ` 4.3.3 Streambed Sediment Conditions 11 4.3.4 Riparian Conditions 12 4.3.5 Water Quality and Quantity Conditions 13 4.3.6 Estuarine Conditions 14 4.4 Salmon Habitat in the Willapa Basin 14 4.4.1 Limiting Factors, Gap Analysis and Methods of Assessment by Watershed 16 4.4.2 Salmon Habitat Assessment in the Willapa Basin by Watershed 18 5.0 Review and Funding Process for Pacific County 44 5.1 Overview 44 5.2 Regulatory Framework 44 5.2.1 Salmon Recover Funding Board (SRFB) 44 5.2.2 Lead Entities 44 5.2.3 Technical Advisory Group (TAG) 45 5.2.4 TAG and