Curriculum As Window and Mirror

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 21 Century Beauty Guide

The 21 st Century Beauty Guide (beauty, inner beauty, modesty, fashion, cosmetic surgery, skincare, acne, hair loss, cosmetics, jewelry, etc.) 2 Save Trees. Read Ebooks. Copyright 2011, peoplepower.co.cc , LLC. This book has a Creative Commons license which means anyone can copy up to 200 of our pages from it to republish anywhere else you want as long as you state you got the material from peoplepower.co.cc , peoplepower.co.cc. 3 Table of Contents Beauty Introduction Volume 1. Beauty Basics Chapter 1. Outer Look & Inner Beauty Outer Look & Inner Beauty 1-2 A Girl’s Appearance/ The Vanity Business The Fine Line Betwwen Dressing For Vanity & Dressing For Self-Respect Physical Beauty 1-3 Chapter 2. The Essence of Beauty Beauty in the Bible The Mechanics of Beauty True Beauty is Love of Life Chapter 3. The Downside of Beauty The Curse of Beauty Nature’s Revenge on Beautiful, Young Women Fashion: The Crown Jewel of Excess Gone Mad Chapter 4. True Beauty is Not Cosmetics Feminine Beauty Info 4 A Straight Guy Talks About Feminine Beauty My Take on the Lie of Feminine Beauty 1-2 Why Men of Substance Can’t Stand Pop Culture Girls Too Much Make-up Chapter 5. We Color Our Hair While Poor Children Starve My Personal Cause: Food not Hair Color Food not Hair Color: Solve World Hunger 1-3 Chapter 6. I Like ‘em Real & Natural Self-Exploitation: Sleaze vs. Wholesome Beauty Betty Page: Natural Beauty, Every Man's Dream Modesty: A Lost Virtue? Daddy's Girl Chapter 7. -

The Temptations and the Four Tops

Nicole'a Macris Nicole'[email protected] 410-900-1151 For Immediate Release THE TEMPTATIONS AND THE FOUR TOPS coming to The Modell Lyric on October 26! Tickets go on sale Friday, April 26th at 10am (BalBmore, MD – April 19) The TEMPTATIONS and The FOUR TOPS together on one stage for one night only at The Modell Lyric on Saturday, October 26 at 7:30pm! THE TEMPTATIONS are notable for their success with Motown Records during the 60’s and 70’s and have sold 10’s of millions of albums, making them one of the most successful groups in music history! For over 40 years The Temptaons have prospered, with an avalanche of smash hits, and sold-out performances throughout the world! “The crowds are bigger, the sales are sizzling,” says one industry report. “The outpouring of affection for this super-group has never been greater”. Beyond their unique blend of voices and flashy wardrobe, The Temptaons became known for their sharp choreography known as “The Temptaon Walk” which became a staple of American style, flair, flash and class and one of the defining legacies of Motown Records. Millions of fans saw the Temptaons as cultural heroes. The group had thirty seven, Top 40 hits to their credit, including fi\een Top 10 hits, fi\een No 1 singles and seventeen No 1 albums spanning from the mid-1960’s to the late 80’s in addiBon to a quartet which soared to No. 1 on the R &B charts. The song Btles alone summon memories beyond measure to include; “The Way You Do The Things You Do,” “My Girl,” “Ain’t Too Proud To Beg,” “I Wish It Would Rain,” “I Can’t Get Next To You”, “Get Ready”, “Just My ImaginaDon (Running Away With Me),” “Ball of Confusion”, “Papa Was A Rollin’ Stone.” “Beauty is Only Skin Deep”, “Cloud Nine,” “Psychedelic Shack”, “Runaway Child”, “Since I Lost My Baby”, “Treat Her Like a Lady” to name a few…. -

Our 60'S R & B, Soul and Motown Song List the Love

Our 60's R & B, Soul and Motown Song List The Love you Save - Michael Jackson I Want you Back - Michael Jackson What Becomes of the Broken Hearted-David Ruffin Tears of a Clown - Smokey Robinson Going to a Go Go- Smokey Robinson Hey there Lonely Girl - Eddie Holeman Tracks of my Tears - Smokey Robinson Ain't no Mountain - Marvin Gaye/ Tammie Terrell Can't take my eyes off of you - Frankie Valli Bernadette - Four Tops Can't Help Myself - Four Tops Standing in the Shadows of Love - Four Tops It's the Same Old Song - Four Tops Reach Out - Four Tops Betcha By Golly Wow - Stylistics But It's Alright - J.J. Jackson You make me feel Brand New - Stylistics Stoned in Love - Stylistics You are Everything - Stylistics Dancin in the Streets - Martha and the Vandellas When a Man Loves a Woman - Percy Sledge Come see about me - Supremes Can't Hurry Love - Supremes Stop in the name of Love - Supremes You keep me Hangin on - Supremes Under the Boardwalk - Drifters Up on the Roof - Drifters Whats Goin On - Marvin Gaye You are the Sunshine - Stevie Wonder Who's Makin Love - Johnny Taylor You Send Me - Sam Cook Hold on I'm Comin - Sam & Dave Soulman - Sam & Dave Heatwave - Martha and the Vandellas I Feel Good - James Brown Get Ready - Temptations My Girl - Temptations Can't get next to you - Temptations Pap was a Rolling Stone - Temptations Cloud Nine - Temptations Just my Imagination - Temptations Phsycadelic Shack - Temptations Page Two 60's R & B, Soul and Motown Song List continued I wish it would Rain - Temptations The Way you do the things you do -

TATLER the TATLER Published Monthly by Henry Waterskjn the Tatierpublishing Corporation W ALTER E

VOL. III SEPTEMBER, 1921 NO.8 otI1HlllIUUlIUIUUIIIIIIIIIIIUlUlmIlUIlIlItIIlIt1ll111lll1lllllll11t1t1ll1l1lt1ll1l111mmm'MlllUtlUUII1I11III1Um"llIIIWl'lllll1111"'II'llIlIIllllllll'III1t111"'ltllllIlIlUI"'''''lll1ll1l11l1111Il''lItlllll'''ll''''''''llllUUtlm'llwmllIlU''U September Daze ~E reason a ~oor~alk~r wears a flower in his buttonhole is because .1. it won't stay In hIs hall'. The chorus girl bread line: From the toast of Broadway to a crumb on Tenth Avenue. Beauty is only skin-deep-and not always knee-high. One thing no married man can understand is why Niagara Falls which is 35,000 years old-is still on its honeymoon. A dumb-waiter is the shortest distance between two gossips. Being in love is like sleeping in a pullman; no one can do it in comfort and some people can't do it at all. Our memory goes back to the time when a " run" in a girl's stocl~ ing was a private affair. When Little Eva began to talk about the angels, she wasn't referring to the backers of the show. The modern dance craze started in the Garden of Eden-with the apple bounce. " Let's be perfectly frank," she said, as she stepped between me and the setting sun. Woman tried to commit suicide by drinking a large bottle of iodine. She said there was a stain on her character. That's neither here nor there, but she certainly has a stain on her interior. Two THE TATLER THE TATLER Published Monthly by Henry WaterSKJn The TatierPublishing Corporation W ALTER E. COLBY president and Treasurer 1819 Broadway, New York City Editor - Single copies, 15 cents, obtained f rem all Waller E. -

'DAVID GEST's SOUL SPECTACULAR!' 3 POP-UP ROLLER BANNERS SOUTHPORT THEATRE.Indd 1 25/09/2010 17:58

18 SOUL LEGENDS ARE COMING TO SOUTHPORT FOR ONE NIGHT ONLY THE CONCERT EVENT OF THE DECADE!!! David Gest’s Soul Spectacular Starring Live In Concert: THE TEMPTATIONS REVIEW FEATURING DENNIS EDWARDS THE ORIGINAL GRAMMY-WINNING LEAD SINGER OF THEIR CLASSIC HITS ‘Papa Was A Rollin’ Stone’ • ‘Ball Of Confusion’ • ‘Cloud Nine’ ‘I Can’t Get Next To You’ • ‘Psychedelic Shack’ • Other Hits Include: ‘My Girl’ • ‘Get Ready’ • ‘Beauty Is Only Skin Deep’ RUSSELL THOMPKINS, JR & THE NEW STYLISTICS ORIGINAL LEAD SINGER OF THE STYLISTICS HITS ‘I Can’t Give You Anything (But My Love)’ • ‘Sing Baby Sing’ ‘You Make Me Feel Brand New’ • ‘Can’t Help Falling In Love’ ‘Na-Na Is The Saddest Word’ • ‘Rock’N’Roll Baby’ PEABO BRYSON ‘Tonight, I Celebrate My Love’ • ‘Beauty and The Beast’ ‘A Whole New World (Aladdin’s Theme)’ LAMONT DOZIER ‘Why Can’t We Be Lovers’ • ‘This Old Heart Of Mine (Is Weak For You)’ ‘My World Is Empty Without You’ • ‘Baby Love’ ‘Stop! In The Name Of Love’ • ‘You Keep Me Hangin’ On’ ‘Fish Ain’t Bitin’ • ‘Reach Out I’ll Be There’ ASHFORD & SIMPSON ‘Solid’ • ‘Ain’t No Mountain High Enough’ • ‘Found A Cure’ ‘Ain’t Nothing Like The Real Thing’ • ‘You’re All I Need To Get By’ BILLY PAUL ‘Me And Mrs. Jones’ • ‘Let ‘Em In’ • ‘Your Song’ HOSTED BY THE TYMES DAVID GEST ‘Ms Grace’ • ‘You Little Trustmaker’ • ‘People’ FREDA PAYNE BRENDA HOLLOWAY ‘Band Of Gold’ • ‘Bring The Boys Home’ ‘Every Little Bit Hurts’ • ‘When I’m Gone’ DOROTHY MOORE DEE DEE SHARP ‘Misty Blue’ • ‘I Believe You’ ‘Mashed Potato Time’ • ‘Ride’ EDDIE FLOYD CANDI STATON ‘Knock On -

The Temptations and the Four Tops to Perform at Four Winds New Buffalo on Friday, April 20

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE THE TEMPTATIONS AND THE FOUR TOPS TO PERFORM AT FOUR WINDS NEW BUFFALO ON FRIDAY, APRIL 20 Tickets go on sale Friday, January 26 NEW BUFFALO, Mich. – January 22, 2018 – The Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians’ Four Winds® Casinos are pleased to announce The Temptations and The Four Tops will perform together at Four Winds New Buffalo’s® Silver Creek® Event Center on Friday, April 20, 2018 at 9 p.m. Hotel and dinner packages are available on the night of the concert. Tickets can be purchased beginning Friday, January 26 at 11 a.m. EST exclusively through Ticketmaster®, www.ticketmaster.com, or by calling (800) 745- 3000. Ticket prices for the show start at $49 plus applicable fees. Four Winds New Buffalo will be offering hotel and dinner packages along with tickets to The Temptations/Four Tops show. The Hard Rock option is available for $460 and includes two concert tickets, a one-night hotel stay on Friday, April 20 and a $50 gift card to Hard Rock Cafe® Four Winds. The Copper Rock option is available for $560 and includes two tickets to the performance, a one-night hotel stay on Friday, April 20 and a $150 gift card to Copper Rock Steak House®. All hotel and dinner packages must be purchased through Ticketmaster. For more than 50 years, The Temptations have prospered, propelling popular music with a series of smash hits, and sold-out performances throughout the world. An essential component of the original Motown machine, The Temptations began their musical life in Detroit in the early sixties. -

Defending Aesthetic Protectionism

Defending Aesthetic Protectionism Ned Hettinger Professor, Philosophy Department College of Charleston Draft Version Published version available in Philosophy: Environmental Ethics, ed. by David Schmidtz (Farmington Hills, Mich.: Macmillan Reference USA, 2017), pp. 287-308. Introduction: What is Aesthetic Protectionism? Environmental beauty is widespread and spectacular. Think of the Colorado Rockies, Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, or the Norwegian fjords. Consider the starry heavens above, the quiet of the desert, or the magnificent parade of life on the Serengeti. Environmental aesthetic merit (or environmental beauty for short)[1] is not just in far off places but is all around us and can be found in humanized environments as well those that are relatively wild. Consider shrimp boats gracing the harbor, cozy pocket parks, cardinals at the feeder, or the wind rustling through the trees. When the environment is degraded, this typically makes it less aesthetically valuable. Imagine a poached elephant without tusks, fish floating belly-up in a polluted creek, trash strewn along the highway, a clear-cut forest, or a deformed mountain lacking its summit. Oil-soaked birds, seals with plastic wrapped around their snouts, belching smokestacks, and abandoned strip malls all combine environmental degradation with aesthetic disvalue. Protecting environmental beauty will typically protect the environment. Environmental beauty is a major motivator for environmental protection. As one commentator notes in a paper called “From Beauty to Duty” (Rolston 2002, 127), “Aesthetic experience is among the most common starting points for an environmental ethic. Ask people, 'Why save the Grand Canyon or the Grand Tetons’, and the ready answer will be, 'Because they are beautiful. -

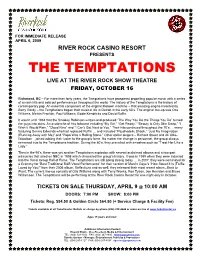

The Temptations

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE APRIL 6, 2009 RIVER ROCK CASINO RESORT PRESENTS THE TEMPTATIONS LIVE AT THE RIVER ROCK SHOW THEATRE FRIDAY, OCTOBER 16 Richmond, BC – For more than forty years, the Temptations have prospered propelling popular music with a series of smash hits and sold out performances throughout the world. The history of the Temptations is the history of contemporary pop. An essential component of the original Motown machine – that amazing engine invented by Berry Gordy – the Temptations began their musical life in Detroit in the early 60’s. The original line-up was Otis Williams, Melvin Franklin, Paul Williams, Eddie Kendricks and David Ruffin. It wasn’t until 1964 that the Smokey Robinson written-and-produced “The Way You Do the Things You Do” turned the guys into stars. An avalanche of hits followed including “My Girl,” “Get Ready,” “Beauty Is Only Skin Deep,” “I Wish It Would Rain,” “Cloud Nine” and “I Can’t Get Next to You.” Their hits continued throughout the 70’s … many featuring Dennis Edwards who had replaced Ruffin … and included “Psychedelic Shack,” “Just My Imagination (Running Away with Me)” and “Papa Was a Rolling Stone.” Other stellar singers – Richard Street and Ali Ollie- Woodson – joined adding their luster to the group’s fame. No matter the change in personnel, the group always remained true to the Temptations tradition. During the 80’s, they prevailed with smashes such as “Treat Her Like a Lady.” Then in the 90’s, there was yet another Temptations explosion with several acclaimed albums and a two-part miniseries that aired on NBC in 1998 which chronicled the group’s history. -

Beauty and Ethics: Three Relations

Beauty And Ethics: Three Relations by Susan Emma Sinclair A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Philosophy Department University of Toronto © Copyright by Sue Sinclair 2014 Beauty and Ethics: Three Relations Susan Emma Sinclair Doctor of Philosophy Philosophy Department University of Toronto 2014 Abstract After years of neglect, a renewed interest in beauty developed among many Western art critics, art practitioners and theorists of aesthetics in the 1990s. Beauty had fallen from favour in part because it was deemed politically and ethically suspect, both as complicit with the sociopolitical structures that yielded WWI and as a tool of oppression wielded against women and minorities. One wonders, however, whether the baby was thrown out with the bathwater. Even granted that beauty has been damaging in the ways alluded to, can it yet be ethically helpful in ways that were lost when we ceased to attend to beauty (at least in the realms of institutional art and aesthetic theory if not in the day to day)? What ethical benefits might we have overlooked? The answer to this question depends partly on what one takes beauty to be. Beauty is a complex concept; there exist many competing and frequently contradictory accounts, often with deep roots, making the concept rife with internal contradictions. Rather than either attempt to reconcile conflicting accounts or address only one aspect of the concept, I will show that different sorts of relation to ethics emerge depending on how we approach beauty. I will present three different ways in which we can see beauty as related to ethics: beauty qua motivator of ethical relation, qua formal cause of ethical relation, and qua analogue of ethical relation. -

Plants Plants

Plants Plants A Theme Unit to Support the Science Management And Resource Tool Spirit-compatible instruction Cooperative learning Multiple intelligences Cross-curricular Hands-on Multi-grade lesson plans (K-8) and practical resources for the one-room or small-school teacher. Written by Kim Kaiser Atlantic Union Conference Teacher Bulletin www.teacherbulletin.org Plants Spirit-compatible Instruction Spirit-compatible instruction is a modification of an approach called Integrated Thematic Instruction (ITI) which is said to be brain-compatible instruction. Spirit-compatible in- struction takes ITI to another level by incorporating and emphasizing the spiritual while addressing the role of the whole person, including body and mind. In the classroom, this approach begins by ensuring that the environment is physically and emotionally safe and supportive of the needs of the brain. We begin by addressing the following environmental issues: - pure air (no odors caused by mildew or chemicals) - pure water - adequate lighting - calming colors and decorations - clutter free and organized - provision for movement Next we work to provide students with an emotional environment characterized by the following: - an assurance of unconditional love - personal significance - absence of threat and strategies for conflict resolution - clear, consistent and fair boundaries - adequate time to complete requirements - meaningful content - interesting and relevant resources - peaceful collaboration with peers - instruction targeted to challenge without overwhelming -

DK Karaoke Song Book

DK Karaoke Songs by Artist Karaoke Shack Song Books Title DiscID Title DiscID 10,000 Maniacs Ace Of Base Candy Everybody Wants DK082-04 Sign, The DK1101-08 Candy Everybody Wants DK3054-08 Sign, The DKMS905-0008 Candy Everybody Wants DKMS910-0093 After 7 10cc Can't Stop DK062-01 I'm Not In Love DK082-14 Ready Or Not DK069-01 I'm Not In Love DK3082-14 A-ha I'm Not In Love DKE34-01 Take On Me DK099-11 I'm Not In Love DKMS910-0392 Take On Me DK3088-11 1910 Fruitgum Company Take On Me DKMS910-0476 Simon Says DK034-15 Air Supply Simon Says DKE29-05 All Out Of Love DK008-13 2Pac All Out Of Love DK3090-14 Dear Mama DK1115-09 All Out Of Love DKMS910-0508 Dear Mama DKH01-06 Lost In Love DK010-03 Dear Mama DKMS905-0210 One That You Love DK3090-13 4 Non Blondes One That You Love, The DK027-10 What's Up DK086-07 One That You Love, The DKMS910-0507 What's Up DK3094-12 Air Supply (Wvocal) What's Up DKMS910-0548 All Out Of Love DKE15-08 4 P.M. Akon Sukiyaki DK089-16 Right Now (Na Na Na) DKMS905-0765 Sukiyaki DK2034-02 Al B Sure Sukiyaki DKMS905-0630 Nite And Day DK046-03 5th Dimension, The Nite And Day DKMS910-0462 Aquarius (Let The Sun Shine In) DK029-05 Al Green Aquarius (Let The Sun Shine In) DK2004-02 Let's Stay Together DK031-01 Aquarius (Let The Sun Shine In) DKMS905-0679 Let's Stay Together DK3059-01 Stoned Soul Picnic DK023-10 Let's Stay Together DKMS910-0161 Stoned Soul Picnic DK3075-02 You Ought To Be With Me DK078-10 Stoned Soul Picnic DKMS910-0277 Al Green & Lyle Lovett Up, Up And Away DK041-14 Funny How Time Slips Away DK092-14 Up, Up And -

Black Box Serie

www.discostars-recordstore.nl Black Box serie elke box bestaat uit 2 cd's Discostars Haarlemmerdijk 86 Amsterdam 020-6261777 2 CD Box € 6,99 per stuk 2 voor € 12,= www.southmiamiplaza.nl South Miami Plaza Albert Cuypstraat 116 Amsterdam 020-6622817 BOB MARLEY CD1 - SUN IS SHINING • NATURAL MYSTIC • LIVELY UP YOURSELF • 400 YEARS DUPPY CONQUERER • CORNER STONE • KEEP ON SKANKING • NO SYMPATHY DRACULA (Mr. Brown Rhythm) • KAYA • REACTION • SOUL SHAKEDOWN PARTY STOP THE TRAIN • AFRICAN HERBSMAN • REBEL’S HOP • CAUTION ADAM & EVE • TRENCH TOWN ROCK 2 CD CD2 - RAINBOW COUNTRY • ALL IN ONE • I LIKE IT LIKE THIS • TREAT YOU RIGHT SATISFY MY SOUL • DOWNPRESSER • MORE AXE • HOW MANY TIMES TELL ME • SOUL REBEL • PICTURE ON THE WALL (Version 4) TURN ME LOOSE • KEEP ON MOVING • MELLOW MOOD • RIDING HIGH DREAMLAND • SOUL ALMIGHTY • BRAIN WASHING 8 712155 079375 COMPACT DISC TRACKS: 36 - PLAYING TIME: 106:31 BB201 THE BEE GEES CD1 - SPICKS & SPECKS • CLAUSTROPHOBIA • FOLLOW THE WIND I AM THE WORLD • SECOND HAND PEOPLE • THEME FROM JAMIE McPHEETERS AND THE CHILDREN LAUGHING • BIG CHANCE • HOW MANY BIRDS I DON’T KNOW WHY I BOTHER WITH MYSELF • MONDAY’S RAIN TURN AROUND, LOOK AT • GLASSHOUSE 2 CD CD2 - EVERYDAY I HAVE TO CRY • COULD IT BE I’M IN LOVE WITH YOU I DON’T THINK IT’S FUNNY • WINE & WOMEN • THREE KISSES OF LOVE TAKE HOLD OF THAT STAR • I WANT HOME • TO BE OR NOT TO BE YOU WOULDN’T KNOW • HOW LONG WAS TRUE • PLAYDOWN THE BATTLE OF THE BLUE AND THE GREY • I WAS A LOVER, A LEADER OF MEN 8 712155 079382 COMPACT DISC TRACKS: 26 - PLAYING TIME: 64:59