UC Berkeley Lamma: a Journal of Libyan Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Between Modernization and Preservation: the Changing Identity of the Vernacular in Italian Colonial Libya

Between Modernization and Preservation: The Changing Identity of the Vernacular in Italian Colonial Libya BRIAN MCLAREN Harvard University This paper concerns the changing identity of the vernacular The architecture of this tourist system balanced a need to project architecture of the Italian colony of Libya in architectural discourse, an image of a modern and efficient network of travel, with the desire and the related appropriation of this re-configured vernacular by to preserve and even accentuate the characteristic qualities of the architects working in thls region. In this effort, I will describe the indigenous culture of each region. In the first instance, the tourist system difference between an abstract assimilation of these influences in the in Libya offered an experience of the colonial context that was early 1930s and a more scientific interest in the indlgenous culture of fundamentally modern-facilities like the dining room at the Albergo Libya in the latter part of this decade. In the first case, the work of "alle Gazzelle" in Zliten conveying an image of metropolitan comfort. architects like Sebastiano Larco and Carlo Enrico Rava subsumed In the second, a conscious effort was made to organize indigenous cultural references to vernacular constructions into modern aesthetic practices. manifestations that would enhance the tourist experience. One In the second, archtects llke Florestano Di Fausto evinced the material prominent example were the musical and dance performances in the qualities of these buildings in works that often directly re-enacted CaffeArabo at the Suq al-Mushr, which were made in a setting that was traditional forms. However, rather than dlscuss the transformation of intended to enact the mysteries of the East. -

Libyan Eclipse 2006

Libyan Eclipse 2006 HIGHLIGHTS PACK Libyan Eclipse 2006 By Anthony Ham Anthony’s love affair with Libya began on his first visit in 2001, and by the time he’d fin- ished Lonely Planet’s guide to Libya a few months later, the country had won his heart. First drawn to the country by its isolation and by his experience elsewhere of the Arab hospitality that puts to shame media stereotyping about the region, Anthony quickly made numerous Libyan friends and set about pursuing his new passion with them – exploring the inexpressible beauty of the Sahara. A full-time writer and photographer, Anthony returns to Libya from his home in Madrid whenever he can and loves the fact that the world is finally discovering that Libya is so much more than Colonel Gaddafi. ALSO AVAILABLE FROM LONELY PLANET Eclipse predictions courtesy of Fred Espenak, NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center. For more information on solar and lunar eclipses, see Fred Espenak’s eclipse home page: http://sunearth.gsfc.nasa.gov/eclipse/eclipse.html. © Lonely Planet 2006. Published by Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd ABN 36 005 607 983 © photographers as indicated 2006. Cover photographs by Lonely Planet Images: Shadows along a ridge of sand dunes in the Awbari Sand Sea, Jane Sweeney; Halo of sunlight glowing around the silhouette of the moon during a total solar eclipse, Karl Lehmann. Many of the images in this guide are available for licensing from Lonely Planet Images: www.lonelyplanetimages.com AVAILABLE APRIL 2006 ORDER NOW All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be copied, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise, except brief extracts for the purpose of review, and no part of this publication may be sold or hired, without the written permission of the publisher. -

The Human Conveyor Belt : Trends in Human Trafficking and Smuggling in Post-Revolution Libya

The Human Conveyor Belt : trends in human trafficking and smuggling in post-revolution Libya March 2017 A NETWORK TO COUNTER NETWORKS The Human Conveyor Belt : trends in human trafficking and smuggling in post-revolution Libya Mark Micallef March 2017 Cover image: © Robert Young Pelton © 2017 Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the Global Initiative. Please direct inquiries to: The Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime WMO Building, 2nd Floor 7bis, Avenue de la Paix CH-1211 Geneva 1 Switzerland www.GlobalInitiative.net Acknowledgments This report was authored by Mark Micallef for the Global Initiative, edited by Tuesday Reitano and Laura Adal. Graphics and layout were prepared by Sharon Wilson at Emerge Creative. Editorial support was provided by Iris Oustinoff. Both the monitoring and the fieldwork supporting this document would not have been possible without a group of Libyan collaborators who we cannot name for their security, but to whom we would like to offer the most profound thanks. The author is also thankful for comments and feedback from MENA researcher Jalal Harchaoui. The research for this report was carried out in collaboration with Migrant Report and made possible with funding provided by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Norway, and benefitted from synergies with projects undertaken by the Global Initiative in partnership with the Institute for Security Studies and the Hanns Seidel Foundation, the United Nations University, and the UK Department for International Development. About the Author Mark Micallef is an investigative journalist and researcher specialised on human smuggling and trafficking. -

The Jebel Nafusa & Ghadames

© Lonely Planet Publications 157 The Jebel Nafusa & Ghadames The barren Jebel Nafusa (Western Mountains) is Libya’s Berber heartland and one of Libya’s most intriguing corners, a land of stone villages on rocky perches and otherworldly Berber architecture. The fortress-like architecture of the jebel reflects the fact that this is a land of extremes. Bitterly cold winters – snowfalls are rare but not unheard of – yield to summers less punishing than elsewhere in Libya, though the southern reaches of the Jebel Nafusa merge imperceptibly with the scorching Sahara. It was to here that many Berbers retreated from invading Arab armies in the 7th century, and the Jebel Nafusa remains one of the few areas in Libya where Berber culture still thrives. Con- sequently, the jebel’s human landscape is as fascinating as its geography and architecture. The Jebel Nafusa merits as much time as you can spare. From the underground houses of Gharyan in the east to the crumbling qasr (fortified granary store) and old town of Nalut in the west, imagination and necessity have fused into the most improbable forms. Nowhere is this more true than in Qasr al-Haj and Kabaw where the wonderful qasrs look like a back- drop to a Star Wars movie. Elsewhere, the abandoned stone village of Tarmeisa surveys the coastal plain from its precipitous rocky perch, while Yefren makes an agreeable base. Beyond the jebel on Libya’s western frontier lies one of the world’s best-preserved oasis towns. Ghadames is an enchanted spot, a labyrinthine caravan town of covered passageways, intricately decorated houses, beautiful palm gardens and a pace of life perfectly attuned to the dictates of the desert. -

Petroleum Generation and Migration in The

Petroleum generation and AUTHORS Ruth Underdown North Africa Research migration in the Ghadames Group, School of Earth, Atmospheric and En- vironmental Sciences, University of Manchester, Basin, north Africa: Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9PL, United Kingdom; [email protected] A two-dimensional Ruth Underdown obtained her first degree in geology from the University of St. Andrews, basin-modeling study Scotland, an M.Sc. degree in petroleum geo- science from Imperial College, London, and a Ph.D. from the University of Manchester, Ruth Underdown and Jonathan Redfern United Kingdom, in 2006, funded by the North Africa Research Group. She is currently teach- ing in the United Kingdom. ABSTRACT Jonathan Redfern North Africa Research The Ghadames Basin contains important oil- and gas-producing res- Group, School of Earth, Atmospheric and En- vironmental Sciences, University of Manchester, ervoirs distributed across Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya. Regional two- Oxford Road, Manchester, M13 9PL, United dimensional (2-D) modeling, using data from more than 30 wells, Kingdom; [email protected] has been undertaken to assess the timing and distribution of hydro- carbon generation in the basin. Four potential petroleum systems Jonathan Redfern obtained his B.Sc. degree in geology from the University of London, Chelsea have been identified: (1) a Middle–Upper Devonian (Frasnian) and College, in 1983, and a Ph.D. from Bristol Uni- Triassic (Triassic Argilo Gre´seux Infe´rieur [TAG-I]) system in the versity, United Kingdom, in 1989. He worked central-western basin; (2) a Lower Silurian (Tannezuft) and Triassic in the oil industry for 12 years, initially with (TAG-I) system to the far west; (3) a Lower Silurian (Tannezuft) and Petrofina in the United Kingdom, southeast Asia, Upper Silurian (Acacus) system in the eastern and northeastern and Libya, and subsequently with Hess. -

Splendors of and Made Themselves Accessible for Questions.”

“Libya has some of the best Roman and Greek archaeological sites I’ve ever seen and they are not overrun with other tourists. Our leaders are excellent sources of information SplendorS of and made themselves accessible for questions.” “Excellent tour—the sites, people, libya guides and cultural experiences were wonderful. It’s a must see and March 16 – 30, 2011 (15 days) experience tour. Thanks for an out- October 19 – November 2, 2011 (15 days) standing experience.” Travel with Dr. Susan Kane, Director of the Cyrenaica Archaeological Project at Cyrene, Libya, and advisor to the Libyan Department of Antiquities. VISIT LIBYA’S SPECTACULAR UNESCO WORLD HERITAGE SITES: • Spend a full day at Cyrene, one of the greatest ancient Greek city-states. Its vast ruins include the Temple of Zeus, which is larger than the Parthenon of Athens. • Admire the magnificent coastal site of Leptis Magna, one of the largest and Above, Leptis Magna’s 16,000 seat amphitheater overlooking the best-preserved Roman cities in the world. Mediterranean. Below, the theater at • Marvel at the Roman city of Sabratha, where the aquamarine sea surrounds Sabratha is considered one of the finest in the remains of partially excavated temples, houses and extensive baths. the Roman world. • Explore the legendary caravan city of Ghadames (Roman Cydamus). HISTORICAL & CULTURAL TREASURES • Discover Tripoli’s Arch of Marcus Aurelius, the Ahmad Pasha al Qaramanli Mosque, and lively souks with a myriad of wares. • Visit the traditional Berber village of Nalut, scenically situated alongside the Jabal Nafusa mountain range, where the Berber settlement dates back to the 11th century. -

Public Summary of Libya Request

On June 16, 2017, the U.S. Department of State published notification in the Federal Register of the receipt of a request from the Government of Libya to the Government of the United States of America for import restrictions on archaeological and ethnological material from Libya representing its prehistoric through Ottoman Era heritage. This request is submitted pursuant to Article 9 of the 1970 UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property as implemented by the Convention on Cultural Property Implementation Act (19 U.S.C. 2601 et seq.). The following public summary, authorized by the Government of Libya, is derived from that request. It does not necessarily represent the position of the Government of the United States on this matter. In its request, the Government of Libya offers a general overview of its geography, climate, and socio-cultural history, evidence of pillage of and jeopardy to its archaeological and ethnological materials, measures Libya has taken consistent with the 1970 UNESCO Convention to mitigate the problem of pillage, analysis of the nature and extent of the U.S. and international market for Libyan cultural property, and description of the benefits that import restrictions might confer. * * * PUBLIC SUMMARY Request by the Government of Libya to the Government of the United States of America for Imposing Import Restrictions to Protect its Cultural Patrimony under Article 9 of the UNESCO Convention (1970) Libya is home to a significant cultural patrimony, which evolved over millennia of human habitation, trade, and development in a geographically vast and diverse setting. -

The Political Economy of Migrant Detention in Libya: Understanding the Players and the Business Models Arezo Malakooti DISCLAIMER

APRIL 2019 The Political Economy of Migrant Detention in Libya: Understanding the players and the business models Arezo Malakooti DISCLAIMER This publication was produced with the financial support of the European Union. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report was prepared, researched and written by Arezo Malakooti. Fieldwork was conducted by Arezo Malakooti, Naji Abou-Khalil, Jerome Veyret, Chiara Fall and Jessica Gerkin. Support was provided by the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime’s local network in Libya. The report also draws on the in-house expertise of Global Initiative Director and Deputy Director, Mark Shaw and Tuesday Reitano, and Senior Fellow Mark Micallef. The report was peer reviewed by experts from the Clingendael Institute: Fransje Molenaar, Floor el Kamouni-Janssen and Mariska van Beijnum. We are also indebted to the various migrants and key informants who graciously shared their stories and experiences with us. The research for this report was supported by funding under the North of Africa window of the EU Emer- gency Trust Fund for Africa. However, the contents of this document are the sole responsibility of the Global Initiative and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union (EU). The photograph on the front cover was taken by the author in a migrant ghetto in Agadez, Niger. Please do not hesitate to contact the author: [email protected] ABOUT THE PROJECT ‘Monitoring the Political Economy of Human Smuggling in Libya and the Greater Sahara’ is a project funded under the North Africa window of the EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa. -

The Ancient Libyan Heritage

Patrimoine sans frontières / Focus on / The ancient Libyan heritage 1st july 2016 Libya is home to a rich and well-preserved heritage little known outside of specialist networks. Today, the country boasts the remains of all of the civilisations which have settled there since the Stone Age. Among them, the wall paintings of the Acacus - a mountainous region in Western Libya - some of which are as old as 12,000 BC. This site, just like Cyrene, Leptis Magna, Sabratha and Ghadames, is on the World Heritage list. As well as these UNESCO sites, the country also hosts numerous relics, tombs, churches and temples from the Byzantine, Umayyad, Ottoman and Italian eras. Cyrene was founded in the 8th century BC and development. Augustus built a forum complying is considered as the oldest Greek colony. Today, with the Roman standards of the time and the it is mostly renowned for its numerous marbles, famous theatre overlooking the Mediterranean was but it also boasts a temple of Zeus bigger than also erected during his reign. Hadrian later gave the the Parthenon in Athens. But the most iconic of city monumental baths, a large part of which still all ancient cities is without a doubt Leptis Magna, stands today. However, the city’s Golden Age really located near the city of Khoms. came about during the reign of Septimus Severus. The Emperor, who was a Libyan native, gave the Originally a Phoenician settlement, the city was city some of its most sumptuous constructions, integrated into the Roman Empire in the 1st century such as the new forum and basilica. -

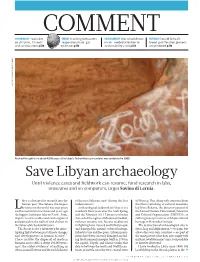

Save Libyan Archaeology Until Violence Eases and Fieldwork Can Resume, Fund Research in Labs, Museums and on Computers, Urges Savino Di Lernia

COMMENT SOCIOBIOLOGY Two takes ENERGY Fracking forecasters SUSTAINABILITY Year of soil draws OBITUARY Donald Metcalf, on altruism, its roots respond on shale-gas much-needed attention to blood-proliferation pioneer, and ramifications p.550 estimates p.553 sustainability crisis p.553 remembered p.554 AIMEN ELSAHLI/REUTERS/CORBIS Rock art thought to be about 4,000 years old in Libya’s Tadrart Acacus mountains was vandalized in 2009. Save Libyan archaeology Until violence eases and fieldwork can resume, fund research in labs, museums and on computers, urges Savino di Lernia. ibya is a hotspot for research into the of the first Saharan state6 during the first of Murzuq. This, along with concerns about human past. The Sahara, the largest millennium bc. the illicit trafficking of cultural materials, hot desert in the world, was once green Archaeological fieldwork in Libya is at a led Irina Bokova, the director-general of Land hosted until a few thousand years ago standstill. Four years after the Arab Spring the United Nations Educational, Scientific the biggest freshwater lake on Earth1. Some and the February 2011 Libyan revolution and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), to depictions of crocodiles and cattle engraved that ended the regime of Muammar Gaddafi, call for greater protection of Libyan cultural and painted on the walls of rock shelters in violence remains rife. Recent escalations heritage in November last year. the Sahara date back 9,000 years. in fighting have injured and killed people The destruction of archaeological sites in The desert is also a laboratory for inves- and damaged the nation’s cultural heritage, Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan — to name but tigating links between past climate changes infrastructure and free press. -

Archaeological Sites of Sabratha and Leptis Magna Reactive Monitoring

Libyan Arab Jamahiriya Archaeological sites of Sabratha Site inscribed on the World Heritage List: C 184 rev. Year 1982, Criteria (iii) and Leptis Magna Site inscribed on the World Heritage List: C 183 rev. Year 1982, Criteria (i), (ii) and (iii) Reactive Monitoring Report January 18-28, 2007 by Mounira BACCAR and François SOUQ 1 Acknowledgments 3 1 CONTEXT AND OBJECTIVES OF THE MISSION 3 Work Method 3 2. SABRATHA 4 2.1. Description of the property 4 2.2. Main threats identified in previous mission reports 4 2.3. State of conservation 5 1. The boundaries are still unclear 2. Damages due to climatic conditions 3. Damages due to maritime action 4. Damages due to inappropriate restorations 5. Vegetation and sand 6. Management of facilities and tourism 7. Management plan 8. Personnel affected to the site 2.4. Conclusions and recommendations 7 3. LEPTIS MAGNA 9 3.1. Description of the property 9 3.2. Main threats identified in previous mission reports 9 3.3. State of conservation 10 1. The Mission would like to note… 2. The Delimitation of the property should be precisely established 3. Management plan 4. Damages due to inappropriate restorations 5. Work related to the presentation of the site 6. The Vegetation 7. Flooding of the Wadi Lebda 8. Facilities and tourism management 3.4. Conclusions and recommendations 12 4. ANNEXES 14 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The mission is attached to express its thanks to Libyan authorities that spared no effort to make this mission as efficient as possible: 1. The Permanent Delegation of Libya to UNESCO, to his Excellency Dr Abdulsalam El Qallali, Ambassador of Libya to UNESCO, and his assistant Mrs. -

The Tribal Structure in Libya: Factor for Fragmentation Or Cohesion?

September 2017 The Tribal Structure in Libya: Factor for fragmentation or cohesion? MOHAMED BEN LAmmA WWW . FRSTRATEGIE . ORG Table of contents INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 3 1 – TRIBALISM IN LIBYA ............................................................................................... 4 2 – TRIBAL COMPOSITION .......................................................................................... 11 2.1 – The most influential tribes in the West of Libya (Tripolitania) ............... 11 2.1.1 – The Warfallah tribe ................................................................................. 12 2.1.2 – The Qadhadfa tribe ................................................................................ 13 2.1.3 – The Zinten tribe ...................................................................................... 14 2.2 – The Tribe in the Barqa region (Cyrenaica) .............................................. 15 2.2.1 – Al-Abaidat tribe ....................................................................................... 15 2.2.2 – Al-Awaqir tribe ........................................................................................ 16 2.2.3 – Zuwaya tribe ........................................................................................... 17 2.2.4 – The tribal map of the Fezzan region ....................................................... 18 2.2.5 – The Awlad Sulaiman tribe ......................................................................