WSSG Newsletter32

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

And Wildlife, 1928-72

Bibliography of Research Publications of the U.S. Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife, 1928-72 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BUREAU OF SPORT FISHERIES AND WILDLIFE RESOURCE PUBLICATION 120 BIBLIOGRAPHY OF RESEARCH PUBLICATIONS OF THE U.S. BUREAU OF SPORT FISHERIES AND WILDLIFE, 1928-72 Edited by Paul H. Eschmeyer, Division of Fishery Research Van T. Harris, Division of Wildlife Research Resource Publication 120 Published by the Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife Washington, B.C. 1974 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Eschmeyer, Paul Henry, 1916 Bibliography of research publications of the U.S. Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife, 1928-72. (Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife. Kesource publication 120) Supt. of Docs. no.: 1.49.66:120 1. Fishes Bibliography. 2. Game and game-birds Bibliography. 3. Fish-culture Bibliography. 4. Fishery management Bibliogra phy. 5. Wildlife management Bibliography. I. Harris, Van Thomas, 1915- joint author. II. United States. Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife. III. Title. IV. Series: United States Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife. Resource publication 120. S914.A3 no. 120 [Z7996.F5] 639'.9'08s [016.639*9] 74-8411 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing OfTie Washington, D.C. Price $2.30 Stock Number 2410-00366 BIBLIOGRAPHY OF RESEARCH PUBLICATIONS OF THE U.S. BUREAU OF SPORT FISHERIES AND WILDLIFE, 1928-72 INTRODUCTION This bibliography comprises publications in fishery and wildlife research au thored or coauthored by research scientists of the Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife and certain predecessor agencies. Separate lists, arranged alphabetically by author, are given for each of 17 fishery research and 6 wildlife research labora tories, stations, investigations, or centers. -

An Ounce of Prevention: Snow Leopard Crime Revisited (PDF, 4

TRAFFIC AN OUNCE REPORT OF PREVENTION: Snow Leopard Crime Revisited OCTOBER 2016 Kristin Nowell, Juan Li, Mikhail Paltsyn and Rishi Kumar Sharma TRAFFIC REPORT TRAFFIC, the wild life trade monitoring net work, is the leading non-governmental organization working globally on trade in wild animals and plants in the context of both biodiversity conservation and sustainable development. TRAFFIC is a strategic alliance of WWF and IUCN. All material appearing in this publication is copyrighted and may be reproduced with permission. Any reproduction in full or in part of this publication must credit TRAFFIC International as the copyright owner. Financial support for TRAFFIC’s research and the publication of this report was provided by the WWF Conservation and Adaptation in Asia’s High Mountain Landscapes and Communities Project, funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The views of the authors expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the TRAFFIC network, WWF, IUCN or the United States Agency for International Development. The designations of geographical entities in this publication, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of TRAFFIC or its supporting organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The TRAFFIC symbol copyright and Registered Trademark ownership is held by WWF. TRAFFIC is a strategic alliance of WWF and IUCN. Suggested citation: Nowell, K., Li, J., Paltsyn, M. and Sharma, R.K. (2016). An Ounce of Prevention: Snow Leopard Crime Revisited. -

Disaggregation of Bird Families Listed on Cms Appendix Ii

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals 2nd Meeting of the Sessional Committee of the CMS Scientific Council (ScC-SC2) Bonn, Germany, 10 – 14 July 2017 UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II (Prepared by the Appointed Councillors for Birds) Summary: The first meeting of the Sessional Committee of the Scientific Council identified the adoption of a new standard reference for avian taxonomy as an opportunity to disaggregate the higher-level taxa listed on Appendix II and to identify those that are considered to be migratory species and that have an unfavourable conservation status. The current paper presents an initial analysis of the higher-level disaggregation using the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World Volumes 1 and 2 taxonomy, and identifies the challenges in completing the analysis to identify all of the migratory species and the corresponding Range States. The document has been prepared by the COP Appointed Scientific Councilors for Birds. This is a supplementary paper to COP document UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.3 on Taxonomy and Nomenclature UNEP/CMS/ScC-Sc2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II 1. Through Resolution 11.19, the Conference of Parties adopted as the standard reference for bird taxonomy and nomenclature for Non-Passerine species the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World, Volume 1: Non-Passerines, by Josep del Hoyo and Nigel J. Collar (2014); 2. -

N° English Name Scientific Name Status Day 1

1 FUNDACIÓN JOCOTOCO CHECK-LIST OF THE BIRDS OF YANACOCHA N° English Name Scientific Name Status Day 1 Day 2 Day 3 1 Tawny-breasted Tinamou Nothocercus julius R 2 Curve-billed Tinamou Nothoprocta curvirostris U 3 Torrent Duck Merganetta armata 4 Andean Teal Anas andium 5 Andean Guan Penelope montagnii U 6 Sickle-winged Guan Chamaepetes goudotii 7 Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis 8 Black Vulture Coragyps atratus 9 Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura 10 Andean Condor Vultur gryphus R Sharp-shinned Hawk (Plain- 11 breasted Hawk) Accipiter striatus U 12 Swallow-tailed Kite Elanoides forficatus 13 Black-and-chestnut Eagle Spizaetus isidori 14 Cinereous Harrier Circus cinereus 15 Roadside Hawk Rupornis magnirostris 16 White-rumped Hawk Parabuteo leucorrhous 17 Black-chested Buzzard-Eagle Geranoaetus melanoleucus U 18 White-throated Hawk Buteo albigula R 19 Variable Hawk Geranoaetus polyosoma U 20 Andean Lapwing Vanellus resplendens VR 21 Rufous-bellied Seedsnipe Attagis gayi 22 Upland Sandpiper Bartramia longicauda R 23 Baird's Sandpiper Calidris bairdii VR 24 Andean Snipe Gallinago jamesoni FC 25 Imperial Snipe Gallinago imperialis U 26 Noble Snipe Gallinago nobilis 27 Jameson's Snipe Gallinago jamesoni 28 Spotted Sandpiper Actitis macularius 29 Band-tailed Pigeon Patagoienas fasciata FC 30 Plumbeous Pigeon Patagioenas plumbea 31 Common Ground-Dove Columbina passerina 32 White-tipped Dove Leptotila verreauxi R 33 White-throated Quail-Dove Zentrygon frenata U 34 Eared Dove Zenaida auriculata U 35 Barn Owl Tyto alba 36 White-throated Screech-Owl Megascops -

Birds of Chile a Photo Guide

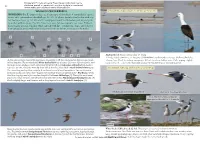

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be 88 distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical 89 means without prior written permission of the publisher. WALKING WATERBIRDS unmistakable, elegant wader; no similar species in Chile SHOREBIRDS For ID purposes there are 3 basic types of shorebirds: 6 ‘unmistakable’ species (avocet, stilt, oystercatchers, sheathbill; pp. 89–91); 13 plovers (mainly visual feeders with stop- start feeding actions; pp. 92–98); and 22 sandpipers (mainly tactile feeders, probing and pick- ing as they walk along; pp. 99–109). Most favor open habitats, typically near water. Different species readily associate together, which can help with ID—compare size, shape, and behavior of an unfamiliar species with other species you know (see below); voice can also be useful. 2 1 5 3 3 3 4 4 7 6 6 Andean Avocet Recurvirostra andina 45–48cm N Andes. Fairly common s. to Atacama (3700–4600m); rarely wanders to coast. Shallow saline lakes, At first glance, these shorebirds might seem impossible to ID, but it helps when different species as- adjacent bogs. Feeds by wading, sweeping its bill side to side in shallow water. Calls: ringing, slightly sociate together. The unmistakable White-backed Stilt left of center (1) is one reference point, and nasal wiek wiek…, and wehk. Ages/sexes similar, but female bill more strongly recurved. the large brown sandpiper with a decurved bill at far left is a Hudsonian Whimbrel (2), another reference for size. Thus, the 4 stocky, short-billed, standing shorebirds = Black-bellied Plovers (3). -

REGUA Bird List July 2020.Xlsx

Birds of REGUA/Aves da REGUA Updated July 2020. The taxonomy and nomenclature follows the Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO), Annotated checklist of the birds of Brazil by the Brazilian Ornithological Records Committee, updated June 2015 - based on the checklist of the South American Classification Committee (SACC). Atualizado julho de 2020. A taxonomia e nomenclatura seguem o Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO), Lista anotada das aves do Brasil pelo Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos, atualizada em junho de 2015 - fundamentada na lista do Comitê de Classificação da América do Sul (SACC). -

Colombia 1 000 Birds Mega Tour II 21St November to 19Th December 2014 (29 Days)

Colombia 1 000 Birds Mega Tour II 21st November to 19th December 2014 (29 days) Lance-tailed Manakin by Dennis Braddy Trip report compiled by Tour Leader: Rob Williams Trip Report - RBT Colombia Mega II 2014 2 An early start on day 1 saw us heading to Mundo Nuevo. Our first stop en route produced a flurry of birds including Northern Mountain Cacique, Golden-fronted Whitestart, Barred Becard, Mountain Elaenia and a Green-tailed Trainbearer feeding young at a nest. We continued up to the altitude where the endemic Flame-winged Parakeets breed and breakfasted while we awaited them. We were rewarded with great scope looks at this threatened species. The area also gave us a flurry of other birds including Scarlet-bellied Mountain Tanager, Rufous-breasted Chat- Tyrant, Pearled Treerunner and Smoke-coloured Pewee. We continued up to the edge of the paramo and birded a track inside Chingaza National Park. Activity was low but we persisted and were rewarded with a scattering of birds including Glossy, Masked and Bluish Flowerpiercers, Slaty Brush Finch, Glowing and Coppery-bellied Pufflegs, and Brown-backed Chat-Tyrant. The endemic Bronze-tailed Thornbill only gave frustrating brief flyby views. Great looks however were had of the endemic Pale-bellied Tapaculo, singing from surprisingly high up in a bush. The track back down gave us Rufous Wren, Superciliated and Black-capped Hemispingus and Tourmaline Sunangel. Further down the road a Buff- breasted Mountain Tanager and some Beryl-spangled Tanagers were found before we headed back to La Calera. After lunch in a local restaurant we headed to the Siecha gravel pits. -

In the Lands of the Romanovs: an Annotated Bibliography of First-Hand English-Language Accounts of the Russian Empire

ANTHONY CROSS In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of The Russian Empire (1613-1917) OpenBook Publishers To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/268 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917) Anthony Cross http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2014 Anthony Cross The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt it and to make commercial use of it providing that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that he endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Cross, Anthony, In the Land of the Romanovs: An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917), Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/ OBP.0042 Please see the list of illustrations for attribution relating to individual images. Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omissions or errors will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. As for the rights of the images from Wikimedia Commons, please refer to the Wikimedia website (for each image, the link to the relevant page can be found in the list of illustrations). -

List of the Birds of Peru Lista De Las Aves Del Perú

LIST OF THE BIRDS OF PERU LISTA DE LAS AVES DEL PERÚ By/por MANUEL A. -

Rochely Santos Morandini

Rochely Santos Morandini Diversidade funcional das aves do Cerrado com simulações da perda de fisionomias campestres e de espécies ameaçadas: implicações para a conservação. (VERSÃO CORRIGIDA – versão original disponível na Biblioteca do IB-USP e na Biblioteca Digital de Teses e Dissertações (BDTD) da USP) Functional Diversity of Cerrado birds with a simulation of the loss of open areas and endangered species: implications for conservation. São Paulo 2013 Rochely Santos Morandini Diversidade funcional das aves do Cerrado com simulações da perda de fisionomias campestres e de espécies ameaçadas: implicações para a conservação. Functional Diversity of Cerrado birds with a simulation of the loss of open areas and endangered species: implications for conservation. Dissertação apresentada ao Instituto de Biociências da Universidade de São Paulo para a obtenção do Título de Mestre em Ciências, na Área de Ecologia. Orientador: Prof. Dr. José Carlos Motta Junior. São Paulo 2013 Morandini, Rochely Santos Diversidade funcional das aves do Cerrado com simulações da perda de fisionomias campestres e de espécies ameaçadas: implicações para conservação. 112 páginas Dissertação (Mestrado) - Instituto de Biociências da Universidade de São Paulo. Departamento de Ecologia. 1. Aves 2. Cerrado 3. Diversidade Funcional I. Universidade de São Paulo. Instituto de Biociências. Departamento de Ecologia Comitê de Acompanhamento: Luís Fábio Silveira Marco Antônio P. L. Batalha Comissão Julgadora: ________________________ ________________________ Prof(a). Dr. Marco Ant ônio Prof(a). Dr. Sergio Tadeu Meirelles Monteiro Granzinolli ____________________________________ Orientador: Prof. Dr. José Carlos Motta Junior Dedicatória A melhor lembrança que tenho da infância são as paisagens de minha terra natal. Dedico este estudo ao Cerrado, com seus troncos retorcidos, seu amanhecer avermelhado, paisagens onde habitam aves tão encantadoras que me tonteiam. -

Reindeer Husbandry/Hunting in Russia in the Past, Present and Future

Reindeer husbandry/hunting in Russia in the past, present and future Leonid M. Baskin The dynamic state of reindeer husbandry in northern Russia during the 20th century was studied as a basis for predicting the consequences of the current drastic changes taking place there. Similar forms and methods of reindeer husbandry were used with different frequencies and effectiveness throughout the century. In the future reindeer husbandry will conform to market requirements, landscape features and national traditions. In some areas, the more sophisticated methods of management developed in conjunction with large-scale, highly productive reindeer husbandry, could be lost and a subsistence economy, including hunting, could predominate. L. M. Baskin, Institute of Ecology and Evolution, 33 Leninsky Prospect, Moscow 117071, Russia. Since 1991, in the Russian North, social and population taken place in response to market economic reconstruction of the rural economy has requirements from the gas and oil industry had a strong impact upon reindeer husbandry. By development (Khmshchev & Klokov 1998). These the 1980s, in northern Russia, reindeer husbandry events are important for the human population of was highly productive (2.3 million domestic northern Russia (about 12 million) of which about reindeer produced for consumption; 4 1.9 thousand 130000 belong to minorities who are closely tonnes live weight). A steep decline occurred in connected with exploitation of reindeer as an the 1990s, and at present in Russia there are ca. 1.6 important food and fur resource. million domestic reindeer. In Chukotka (see This paper’s aim is to evaluate the ecological and Fig. I) their numbers declined from 500000 to social consequences of ongoing changes in reindeer 130OOG, and large declines were observed in husbandry. -

Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast

FEDERAL STATE BUDGETARY INSTITUTION OF SCIENCE VOLOGDA RESEARCH CENTER OF THE RUSSIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL CHANGES: FACTS, TRENDS, FORECAST Volume 11, Issue 5, 2018 The journal was founded in 2008 Publication frequency: six times a year According to the Decision of the Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation, the journal Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast is on the List of peer-reviewed scientific journals and editions that are authorized to publish principal research findings of doctoral (candidate’s) dissertations in scientific specialties: 08.00.00 – economic sciences; 22.00.00 – sociological sciences. The journal is included in the following abstract and full text databases: Web of Science (ESCI), ProQuest, EBSCOhost, Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ), RePEc, Ulrich’s Periodicals Directory, VINITI RAS, Russian Science Citation Index (RSCI). The journal’s issues are sent to the U.S. Library of Congress and to the German National Library of Economics. All research articles submitted to the journal are subject to mandatory peer-review. Opinions presented in the articles can differ from those of the editor. Authors of the articles are responsible for the material selected and stated. ISSN 2307-0331 (Print) ISSN 2312-9824 (Online) © VolRC RAS, 2018 Internet address: http://esc.vscc.ac.ru ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL CHANGES: FACTS, TRENDS, FORECAST A peer-reviewed scientific journal that covers issues of analysis and forecast of changes in the economy and social spheres in various countries, regions, and local territories. The main purpose of the journal is to provide the scientific community and practitioners with an opportunity to publish socio-economic research findings, review different viewpoints on the topical issues of economic and social development, and participate in the discussion of these issues.