Iceland a Small Media System Facing Increasing Challenges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

S12904-021-00797-0.Pdf

Bylund‑Grenklo et al. BMC Palliat Care (2021) 20:99 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904‑021‑00797‑0 CORRECTION Open Access Correction to: Acute and long‑term grief reactions and experiences in parentally cancer‑bereaved teenagers Tove Bylund-Grenklo1*†, Dröfn Birgisdóttir2*†, Kim Beernaert3,4, Tommy Nyberg5,6, Viktor Skokic6, Jimmie Kristensson2,7, Gunnar Steineck6,8, Carl Johan Fürst2 and Ulrika Kreicbergs9,10 Sciences, Gothenburg, Sweden. 9 Department of Caring Sciences, Palliative Correction to: BMC Palliat Care 20, 75 (2021) Research Center, Ersta Sköndal Bräcke University College, Stockholm, Sweden. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-021-00758-7 10 Department of Women’s and Children’s Health, Karolinska Institutet, Stock- Following publication of the original article [1], the holm, Sweden. authors identifed an error in the author name of Kim Beernaert. Te incorrect author name is: Kim Beenaert. Te correct author name is: Kim Beernaert. Te author group has been updated above and the orig- Reference inal article [1] has been corrected. 1. Bylund-Grenklo T, Birgisdóttir D, Beernaert K, et al. Acute and long- term grief reactions and experiences in parentally cancer-bereaved teenagers. BMC Palliat Care. 2021;20:75. https:// doi. org/ 10. 1186/ Author details s12904- 021- 00758-7. 1 Department of Caring Science, Faculty of Health and Occupational Studies, University of Gävle, 801 76 Gävle, Sweden. 2 Faculty of Medicine, Department of Clinical Sciences Lund, Oncology and Pathology, Institute for Palliative Care, Lund University and Region Skåne, Medicon Village, Hus 404B, 223 81 Lund, Sweden. 3 End-of-Life Care Research Group, Ghent University & Vrije Univer- siteit Brussel (VUB), Ghent, Belgium. -

Marla J. Koberstein

Master‘s thesis Expansion of the brown shrimp Crangon crangon L. onto juvenile plaice Pleuronectes platessa L. nursery habitat in the Westfjords of Iceland Marla J. Koberstein Advisor: Jόnas Páll Jόnasson University of Akureyri Faculty of Business and Science University Centre of the Westfjords Master of Resource Management: Coastal and Marine Management Ísafjörður, February 2013 Supervisory Committee Advisor: Name, title Reader: Name, title Program Director: Dagný Arnarsdóttir, MSc. Marla Koberstein Expansion of the brown shrimp Crangon crangon L. onto juvenile plaice Pleuronectes platessa L. nursery habitat in the Westfjords of Iceland 45 ECTS thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of a Master of Resource Management degree in Coastal and Marine Management at the University Centre of the Westfjords, Suðurgata 12, 400 Ísafjörður, Iceland Degree accredited by the University of Akureyri, Faculty of Business and Science, Borgir, 600 Akureyri, Iceland Copyright © 2013 Marla Koberstein All rights reserved Printing: Háskólaprent, Reykjavik, February 2013 Declaration I hereby confirm that I am the sole author of this thesis and it is a product of my own academic research. __________________________________________ Student‘s name Abstract Sandy-bottom coastal ecosystems provide integral nursery habitat for juvenile fishes, and threats to these regions compromise populations at this critical life stage. The threat of aquatic invasive species in particular can be difficult to detect, and climate change may facilitate the spread and establishment of new species. In 2003, the European brown shrimp Crangon crangon L. was discovered off the southwest coast of Iceland. This species is a concern for Iceland due to the combination of its dominance in coastal communities and level of predation on juvenile flatfish, namely plaice Pleuronectes platessa L., observed in its native range. -

Elements of Nature Relocated the Work of Studio Granda

Petur H. Armannsson Elements of Nature Relocated The Work of Studio Granda "Iceland is not scenic in the conventional European sense of The campus of the Bifrost School of Business is situated in the word - rather it is a landscape devoid of scenery. Its qual- Nordurardalur Valley in West Iceland, about 60 miles North ity of hardness and permanence intercut v/\1\-i effervescent of the capital city of Reykjavik. Surrounded by mountains elements has a parallel in the work of Studio Granda/" of various shapes and heights, the valley is noted for the beauty of its landscape. The campus is located at the edge of a vast lava field covered by gray moss and birch scrubs, w/ith colorful volcanic craters forming the background. The main road connecting the northern regions of Iceland with the Reykjavik area in the south passes adjacent to the site, and nearby is a salmon-fishing river with tourist attracting waterfalls. The original building at Bifrost was designed as a res- taurant and roadway hotel. It was built according to plans made in 1945 by architects Gisli Halldorsson and Sigvaldi Thordarson. The Federation of Icelandic Co-op- eratives (SIS) bought the property and the first phase of the hotel, the restaurant wing, was inaugurated in 1951. It functioned as a restaurant and community center of the Icelandic co-operative movement until 1955, when a decision was made to move the SIS business trade school there from Reykjavik. A two-story hotel wing with Armannsson 57 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/thld_a_00361 by guest on 24 September 2021 hotel rooms was completed that same year and used as In subsequent projects, Studio Granda has continued to a student dormitory in the winter. -

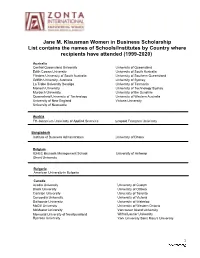

2020 JMK Schools

Jane M. Klausman Women in Business Scholarship List contains the names of Schools/Institutes by Country where recipients have attended (1999-2020) Australia Central Queensland University University of Queensland Edith Cowan University University of South Australia Flinders University of South Australia University of Southern Queensland Griffith University, Australia University of Sydney La Trobe University Bendigo University of Tasmania Monash University University of Technology Sydney Murdoch University University of the Sunshire Queensland University of Technology University of Western Australia University of New England Victoria University University of Newcastle Austria FH-Joanneum University of Applied Sciences Leopold Franzens University Bangladesh Institute of Business Administration University of Dhaka Belgium ICHEC Brussels Management School University of Antwerp Ghent University Bulgaria American University in Bulgaria Canada Acadia University University of Guelph Brock University University of Ottawa Carleton University University of Toronto Concordia University University of Victoria Dalhousie University University of Waterloo McGill University University of Western Ontario McMaster University Vancouver Island University Memorial University of Newfoundland Wilfrid Laurier University Ryerson University York University Saint Mary's University 1 Chile Adolfo Ibanez University University of Santiago Chile University of Chile Universidad Tecnica Federico Santa Maria Denmark Copenhagen Business School Technical University of Denmark -

Hunting Reindeer in East Iceland

Master’s Thesis Hunting Reindeer in East Iceland The Economic Impact Stefán Sigurðsson Supervisors: Vífill Karlsson Kjartan Ólafsson University of Akureyri School of Business and Science February 2012 Acknowledgements The parties listed below are thanked for their contribution to this thesis. Vífill Karlsson, consultant and assistant professor, department of business administration, University of Akureyri, for his patience and outstanding work as supervisor. Kjartan Ólafsson, lecturer, faculty of humanities and social sciences, University of Akureyri, for his work and comments as supervisor. Guðmundur Kristján Óskarsson, lecturer, department of business administration, University of Akureyri, for his assistance when processing statistics. Jón Þorvaldur Heiðarsson, lecturer, department of business administration, University of Akureyri, and researcher, Research Center University of Akureyri, for his comments. Ögmundur Knútsson, lecturer, department of business administration, University of Akureyri, for his comments. Steinar Rafn Beck, advisor, department of natural resource sciences, for valuable information when working on this master thesis. Bjarni Pálsson, divisional manager, Department for natural resource sciences, for valuable information when working on this master thesis. Rafn Kjartansson, translator and language reviewer of this work. Astrid Margrét Magnúsdóttir, director of Information Services, University of Akureyri, for her comments on documentation and references. ---------------------------------------------------------- Stefán Sigurðsson ii Abstract Tourism in Iceland is of great importance and ever-growing. During the period 2000- 2008 the share of tourism in GDP was 4.3% to 5.7%. One aspect of the tourist industry is hunting tourism, upon which limited research has been done and only fragmented information exists on the subject. The aim of this thesis is to estimate the economic impact of reindeer hunting on the hunting area. -

Volcanogenic Floods in Iceland: an Exploration of Hazards and Risks

I. VOLCANOGENIC FLOODS IN ICELAND: AN EXPLORATION OF HAZARDS AND RISKS Emmanuel Pagneux *, Sigrún Karlsdóttir *, Magnús T. Gudmundsson **, Matthew J. Roberts * and Viðir Reynisson *** 1 * Icelandic Meteorological Office ** Nordic Volcanological Centre, Institute of Earth Sciences, University of Iceland *** National Commissioner of the Icelandic Police, Department of Civil Protection and Emergency Management 1. Introduction where the recurrence time of eruptions is about 50 years. The largest of these eruptions This publication presents the results from an have caused rapidly rising floods with a exploratory project on the risk assessment of maximum discharge 100–300,000 m3/s (e.g. glacial outburst floods (jökulhlaups) caused Tómasson, 1996; Larsen, 2000; Elíasson et by volcanic eruptions in Iceland. Such floods al., 2006). result from the interaction of hot freshly The largest hazard and risk to life in erupted lava, tephra or hot gases with glacier volcanogenic floods occurs on populated ice and snow on the slopes of volcanoes. slopes of large, steep-sided ice-clad Jökulhlaups related to volcanic activity, volcanoes. This particular environment is caused both directly by volcanic eruptions found in Iceland on the foothills of and indirectly through geothermal activity, Eyjafjallajökull, Snæfellsjökull and Öræfa- are one of the main volcanogenic hazards in jökull volcanoes. The most severe events Iceland (Gudmundsson et al., 2008). Over have occurred at Öræfajökull, which erupted half of all Icelandic eruptions occur in ice in 1362 and 1727. On both occasions the covered volcanoes, resulting either directly or eruptions and the associated floods lead to indirectly in jökulhlaups (Larsen et al., 1998; destruction, devastation and loss of life Larsen, 2002). -

Participants List for Does Size Matter?

Participants list for Does size matter? - Universities competing in a global market/Liste des participants pour Est-ce que la taille importe ? La compétition universitaire dans un marché mondialisé. Reykjavik, Iceland 4/6/2008 - 6/6/2008 Jarle AARBAKKE Rector University of Tromsoe Norway Lena ADAMSON Principal secretary The Swedish National Agency for Higher Education Sweden Charlotte ALLER Senior Adviser Copenhagen Business School Denmark Ellen ALMGREN Project Manager Department of Statistics and Analysis Swedish National Agency for Higher Education Sweden Yvonne ANDERSSON Faculty Director Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Sweden Lena ANDERSSON-EKLUND Pro-Vice-Chancellor Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Sweden Dagny Osk ARADOTTIR University of Iceland Iceland Marcis AUZINSH Rector University of Latvia Latvia Magnus BALDURSSON Assistant to the Rector - Rector's Office The University of Iceland Iceland Jón Atli BENEDIKTSSON Rector's Office University of Iceland Iceland 1 Göran BEXELL Vice-Chancellor Lund University Sweden Jens BIGUM Chairman University of Aarhus Denmark Susanne BJERREGAARD Sectretary General Universities Denmark Denmark Thomas BOLAND Chief Executive Higher Education Authority Ireland Poul BONDE International Secretariat Aarhus Universitet Denmark Mikkel BUCHTER Special Adviser - Art and Education Ministry of Culture Denmark Steve CANNON University Secretary – Secretary’s Office University of Aberdeen United Kingdom Oon Ying CHIN Counsellor for Education Australian Department of Education, Employment -

Download the Conference Programme

UN photo Putting the Responsibility to Protect at the Centre of Europe October 13-14, 2016 University of Leeds Conference Programme Putting the Responsibility to Protect at the Centre of Europe Conference Programme Day 1, Thursday 13 October Venue: Great Woodhouse Room, University House 10.15 Welcome: Jason Ralph, Head of the School of Politics and International Studies (POLIS), University of Leeds. 10.30 Opening Plenary: The global state of R2P Chair: Jason Ralph, University of Leeds • Simon Adams, Director of the Global Center for R2P • Gillian Kitley, Senior Officer, United Nations Office for the Prevention of Genocide and the R2P • Phil Orchard, University of Queensland and Research Director of the Asia Pacific Centre for R2P (via Skype) • Adrian Gallagher, POLIS, University of Leeds 12.30 - 13.30 Buffet lunch 13.30 - 15.00 Plenary Roundtable 1: European Perspectives of R2P Chair: Edward Newman, University of Leeds • Jennifer Welsh, European University Institute, former UN Special Adviser on the R2P (via Skype) • Cristina Stefan, POLIS, University of Leeds • Chiara De Franco, University of Southern Denmark • Enzo Maria Le Fevre Cervini, Director of Research and Cooperation of the Budapest Centre for the International Prevention of Genocide and Mass Atrocities • Fabien Terpan, College of Europe, Sciences Po Grenoble 15.00 - 15.30 Coffee 15.30 - 16.30 Plenary Roundtable 2: European Perspectives of R2P Chair: Eamon Aloyo, Hague Institute • Christoph Meyer, King’s College London • Vasilka Sancin, Faculty of Law, University of Ljubljana -

Church Topography and Episcopal Influence in Northern Iceland 1106‐1318 AD

Power and Piety: Church Topography and Episcopal Influence in Northern Iceland 1106‐1318 A.D. By Egil Marstein Bauer Master Thesis in Archaeology Department of Archaeology, Conservation and History University of Oslo Spring 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES................................................................................................................................I LIST OF TABLES ..............................................................................................................................III ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS................................................................................................................. V 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Presentation of Thesis with Background Information............................................................. 1 1.2 Comparison with Trøndelag, Norway ..................................................................................... 4 1.3 Structure of the Thesis............................................................................................................. 6 2 PREVIOUS RESEARCH ............................................................................................................ 9 3 CHURCH MATERIAL.............................................................................................................. 13 3.1 Churches in the Written Material ......................................................................................... -

A3ES, 97 Aalborg University, Ix, 151 Academic Careers (Women And) Career Progression, 3–22, 80, 116, 118, 120, 139–40, 153

Index A3ES, 97 social capital and, 5, 9, 142, 159, Aalborg University, ix, 151 184–7 academic careers (women and) sponsors, 5, 170, 174, 176, 182, career progression, 3–22, 80, 116, 184, 188, 191–2 118, 120, 139–40, 153, 173, traditional career path, 3, 13, 144, 177, 181, 186, 192 175, 180, 187, 189–90 casualised workforce, 86, 131–4, 171 Acar, F., 132, 153, 160 class and, 5, 9, 12–14, 23–7, 40, Acker, S., 15, 16, 63 46–52, 67, 89, 105–8, 117, 133, Acker, S. and Armenti, S., 7, 16, 147, 160, 169, 175–85, 188, 185, 192 191–2 Acker, S. and Feuerverger, G., cultural capital and, 5, 28, 31, 174, 192 141–2, 159, 181–2 Ackers, L., 146, 160, 180, 190, 192 entitlement, 8, 26, 30, 34, 38, 176–80, 192 Adelaide, 74, 77, 113 Adesina, J., 133, 161 family influence on, 5, 15, 23–5, 43, Akmut, Prof, 151 46–51, 66–7, 74, 80, 83–5, 97, Alvesson, M. and Sköldberg, K., 103–6, 128, 130–1, 141, 146–8, 127, 161 153–4, 159–60, 175–80 Alvesson, M. and Sveningsson, S., 37, feminist academics, 3–5, 8, 14–15, 43 27, 32, 41–3, 54–5, 70–3, 76, Amâncio, L., 97, 100 79–80, 107, 117, 127, 133, 139, Amaral, A., 94–5, 97–8 143, 158, 173–6, 190–1 Ankara, 149–50, 186 future challenges, 188–90 Ankara University, 149–53, gender identity, 9, 30, 54, 87–92, 186 106–9, 182, 187–8 Ashall, S., 179, 185, 192 generational change, 3–6, 79, 83, Asmar, C., 10, 16 128, 154, 159–60, 168–95 Association of Social Science influence of matriarchies on, 46–50, Researchers, 80 70–3, 106, 176 ATGender, 55 life-course and, 5, 9, 12 –15, 189 Aturtuk, M.K., 148 mobility, 5, 146, 151–2, 156, 180–1, Australasian Evaluation Society, 80 191–2 Australia, 7, 10, 39, 106, 112–13, 115, organisational culture, 5, 7–9, 172–5 128, 157 outsiders, 5, 27, 51, 53, 105–9, 178–80 Babbie, E., Mouton, J., Payze, C., playing the ‘game’ (or not), 5, 30–5, Vorster, J. -

Tommaso M. Milani

CURRICULUM VITAE – TOMMASO M. MILANI Address: 65 Fifth Avenue, Melville, 2092 South Africa Email: [email protected] Nationality/ Italian (Passport No YA4035454) Citizenship EDUCATION 2007 Ph.D. Centre for Research on Bilingualism, Stockholm University, Sweden. Bilingualism Research Supervisors: Kenneth Hyltenstam (Professor Emeritus, Stockholm University); Sally Johnson (Professor Emeritus, University of Leeds) 1998 M.A. Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milan, Italy. Foreign Languages and Literatures (summa cum laude) ACADEMIC POSITIONS July 2012 – June 2015 Head of Department Department of Linguistics, School of Literature, Language and Media, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg Oct. 2010 – present Associate Professor Department of Linguistics, School of Literature and Language Studies, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. Jan. 2009 – Sept. 2010 Senior Lecturer Department of Linguistics, School of Literature and Language Studies, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. Early confirmation of the position in February 2010. 2007 – 2008 Post-doctoral Research Fellow on AHRC-funded BBC “Voices” project Department of Linguistics and Phonetics, School of Modern Languages and Cultures, University of Leeds, UK. Principal investigator: Professor Sally Johnson. 2003 – 2007 Ph.D. position (with administrative and teaching duties) Centre for Research on Bilingualism, Stockholm University, Sweden. 1 VISITING RESEARCHER POSITIONS July – Sept. 2015 Department of Child and Youth Studies Stockholm University September -

Behind the Paywall: a Cross-Thematic Conference on the Implications of the Budding Market for Paid-For Online News

Conference Call Behind the Paywall: A Cross-Thematic Conference on the Implications of the Budding Market for Paid-for Online News Host: Nordicom Venue: The University of Gothenburg (Sweden) Date: January 23–24, 2019 Deadline for extended abstracts: November 15, 2018 The past few years have seen a dramatic upsurge in paywalls being erected across the news media landscape. Online news content that was previously circulated for free is now available only to those who are willing to pay for it. The paywalls are an industry response to two interacting market forces: the gradual decline in printed newspaper sales and the increasing dominance of global networking platforms such as Google and Facebook on national and local advertising markets. In order for commercially funded news media outlets to survive, online audience revenue seems to be the most viable way forward. The implications of what appears to be a fundamental shift from “free-for-all” to “subscribers-only” access to online news, are plentiful. As a research area, it raises important questions regarding such diverse topics as digital business models and digital media policy, journalistic processes and journalistic content, news media audiences and news media use, and – indeed – the democratic function of commercial news media at large. What happens with news media products and what happens with news media audiences when paywalls are erected? What happens with those that chose not to pay? And how does this metamorphosis of the private news media sector affect the role and scope of public service media? Against the backdrop of these rather fundamental questions, Nordicom (Nordic Information Centre for Media and Communication Research at the University of Gothenburg) invites the international research community to a two-day conference devoted to the paywall phenomenon.