University of Cincinnati

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moral Rights: the Anti-Rebellion Graffiti Heritage of 5Pointz Richard H

digitalcommons.nyls.edu Faculty Scholarship Articles & Chapters 2018 Moral Rights: The Anti-Rebellion Graffiti Heritage of 5Pointz Richard H. Chused New York Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/fac_articles_chapters Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, Land Use Law Commons, and the Property Law and Real Estate Commons Recommended Citation Chused, Richard H., "Moral Rights: The Anti-Rebellion Graffiti Heritage of 5Pointz" (2018). Articles & Chapters. 1172. https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/fac_articles_chapters/1172 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles & Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@NYLS. Moral Rights: The Anti-Rebellion Graffiti Heritage of 5Pointz Richard Chused* INTRODUCTION Graffiti has blossomed into far more than spray-painted tags and quickly vanishing pieces on abandoned buildings, trains, subway cars, and remote underpasses painted by rebellious urbanites. In some quarters, it has become high art. Works by acclaimed street artists Shepard Fairey, Jean-Michel Basquiat,2 and Banksy,3 among many others, are now highly prized. Though Banksy has consistently refused to sell his work and objected to others doing so, works of other * Professor of Law, New York Law School. I must give a heartfelt, special thank you to my artist wife and muse, Elizabeth Langer, for her careful reading and constructive critiques of various drafts of this essay. Her insights about art are deeply embedded in both this paper and my psyche. Familial thanks are also due to our son, Benjamin Chused, whose knowledge of the graffiti world was especially helpful in composing this paper. -

University of Cincinnati

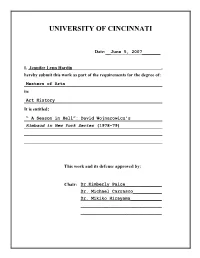

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:__June 5, 2007_______ I, Jennifer Lynn Hardin_______________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Masters of Arts in: Art History It is entitled: “ A Season in Hell”: David Wojnarowicz’s Rimbaud in New York Series (1978-79) This work and its defense approved by: Chair: Dr.Kimberly Paice______________ Dr. Michael Carrasco___________ Dr. Mikiko Hirayama____________ _______________________________ _______________________________ “A Season in Hell”: David Wojnarowicz’s Rimbaud In New York Series (1978-79) A thesis submitted to the Art History Faculty of the College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning University of Cincinnati In candidacy for the degree of Masters of Arts in Art History Jennifer Hardin June 2007 Advisor: Dr. Kimberly Paice Abstract David Wojnarowicz (1954-1992) was an interdisciplinary artist who rejected traditional scholarship and was suspicious of institutions. Wojnarowicz’s Arthur Rimbaud in New York series (1978-79) is his earliest complete body of work. In the series a friend wears the visage of the French symbolist poet. My discussion of the photographs involves how they convey Wojnarowicz’s notion of the city. In chapter one I discuss Rimbaud’s conception of the modern city and how Wojnarowicz evokes the figure of the flâneur in establishing a link with nineteenth century Paris. In the final chapters I address the issue of the control of the city and an individual’s right to the city. In chapter two I draw a connection between the renovations of Paris by Baron George Eugène Haussman and the gentrification Wojnarowicz witnessed of the Lower East side. -

5Pointz Decision

Case 1:13-cv-05612-FB-RLM Document 172 Filed 02/12/18 Page 1 of 100 PageID #: 4939 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK --------------------------------------------------x JONATHAN COHEN, SANDRA Case No. 13-CV-05612(FB)(RLM) FABARA, STEPHEN EBERT, LUIS LAMBOY, ESTEBAN DEL VALLE, RODRIGO HENTER DE REZENDE, DANIELLE MASTRION, WILLIAM TRAMONTOZZI, JR., THOMAS LUCERO, AKIKO MIYAKAMI, CHRISTIAN CORTES, DUSTIN SPAGNOLA, ALICE MIZRACHI, CARLOS GAME, JAMES ROCCO, STEVEN LEW, FRANCISCO FERNANDEZ, and NICHOLAI KHAN, Plaintiffs, -against- G&M REALTY L.P., 22-50 JACKSON DECISION AVENUE OWNERS, L.P., 22-52 JACKSON AVENUE, LLC, ACD CITIVIEW BUILDINGS, LLC, and GERALD WOLKOFF, Defendants. --------------------------------------------------x MARIA CASTILLO, JAMES COCHRAN, Case No. 15-CV-3230(FB)(RLM) LUIS GOMEZ, BIENBENIDO GUERRA, RICHARD MILLER, KAI NIEDERHAUSEN, CARLO NIEVA, RODNEY RODRIGUEZ, and KENJI TAKABAYASHI, Plaintiffs, -against- Case 1:13-cv-05612-FB-RLM Document 172 Filed 02/12/18 Page 2 of 100 PageID #: 4940 G&M REALTY L.P., 22-50 JACKSON AVENUE OWNERS, L.P., 22-52 JACKSON AVENUE, LLC, ACD CITIVIEW BUILDINGS, LLC, and GERALD WOLKOFF, Defendants. -----------------------------------------------x Appearances: For the Plaintiff For the Defendant ERIC BAUM DAVID G. EBERT ANDREW MILLER MIOKO TAJIKA Eisenberg & Baum LLP Ingram Yuzek Gainen Carroll & 24 Union Square East Bertolotti, LLP New York, NY 10003 250 Park Avenue New York, NY 10177 BLOCK, Senior District Judge: TABLE OF CONTENTS I ..................................................................5 II ..................................................................6 A. The Relevant Statutory Framework . 7 B. The Advisory Jury . 11 C. The Witnesses and Evidentiary Landscape. 13 2 Case 1:13-cv-05612-FB-RLM Document 172 Filed 02/12/18 Page 3 of 100 PageID #: 4941 III ................................................................16 A. -

KREVISS Cargo Records Thanks WW DISCORDER and All Our Retail Accounts Across the Greater Vancouver Area

FLAMING LIPS DOWN BY LWN GIRL TROUBLE BOMB ATOMIC 61 KREVISS Cargo Records thanks WW DISCORDER and all our retail accounts across the greater Vancouver area. 1992 was a good year but you wouldn't dare start 1993 without having heard: JESUS LIZARD g| SEBADOH Liar Smash Your Head IJESUS LIZARD CS/CD On The Punk Rock CS/CD On Sebadoh's songwriter Lou Barlow:"... (his) songwriting sticks to your gullet like Delve into some raw cookie dough, uncharted musical and if he ever territory. overcomes his fascination with the The holiday season sound of his own being the perfect nonsense, his time for this baby Sebadoh could be from Jesus Lizard! the next greatest band on this Hallelujah! planet". -- Spin ROCKET FROM THE CRYPT Circa: Now! CS/CD/LP San Diego's saviour of Rock'n'Roll. Forthe ones who Riff-driven monster prefer the Grinch tunes that are to Santa Claus. catchier than the common cold and The most brutal, loud enough to turn unsympathetic and your speakers into a sickeningly repulsive smoldering heap of band ever. wood and wires. A must! Wl Other titles from these fine labels fjWMMgtlllli (roue/a-GO/ are available through JANUARY 1993 "I have a responsibility to young people. They're OFFICE USE ONLY the ones who helped me get where I am today!" ISSUE #120 - Erik Estrada, former CHiPs star, now celebrity monster truck commentator and Anthony Robbins supporter. IRREGULARS REGULARS A RETROSPECT ON 1992 AIRHEAD 4 BOMB vs. THE FLAMING LIPS COWSHEAD 5 SHINDIG 9 GIRL TROUBLE SUBTEXT 11 You Don't Go To Hilltop, You VIDEOPHILTER 21 7" T\ REAL LIVE ACTION 25 MOFO'S PSYCHOSONIC PIX 26 UNDER REVIEW 26 SPINLIST. -

App. 1 950 F.3D 155 (2D Cir. 2020) United States Court of Appeals

App. 1 950 F.3d 155 (2d Cir. 2020) United States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit Maria CASTILLO, James Cochran, Luis Gomez, Bien- benido Guerra, Richard Miller, Carlo Nieva, Kenji Taka- bayashi, Nicholai Khan, Plaintiffs-Appellees, Jonathan Cohen, Sandra Fabara, Luis Lamboy, Esteban Del Valle, Rodrigo Henter De Rezende, William Tramon- tozzi, Jr., Thomas Lucero, Akiko Miyakami, Christian Cortes, Carlos Game, James Rocco, Steven Lew, Francisco Fernandez, Plaintiffs-Counter- Defendants-Appellees, Kai Niederhause, Rodney Rodriguez, Plaintiffs, v. G&M REALTY L.P., 22-50 Jackson Avenue Owners, L.P., 22-52 Jackson Avenue LLC, ACD Citiview Buildings, LLC, and Gerald Wolkoff, Defendants-Appellants. Nos. 18-498-cv (L), 18-538-cv (CON) August Term 2019 Appeal from the United States District Court for the Eastern District of New York Nos. 15-cv-3230 (FB) (RLM), 13-cv-5612 (FB) (RLM), Frederic Block, District Judge, Presiding. Argued August 30, 2020 Decided February 20, 2020 Amended February 21, 2020 Attorneys and Law Firms ERIC M. BAUM (Juyoun Han, Eisenberg & Baum, LLP, New York, NY, Christopher J. Robinson, Rottenberg Lipman Rich, P.C., New York, NY, on the brief), Eisenberg & Baum, LLP, New York, NY, for Plaintiffs-Appellees. MEIR FEDER (James M. Gross, on the brief), Jones Day, New York, NY, for Defendants-Appellants. App. 2 Before: PARKER, RAGGI, and LOHIER, Circuit Judges. BARRINGTON D. PARKER, Circuit Judge: Defendants‐Appellants G&M Realty L.P., 22‐50 Jack- son Avenue Owners, L.P., 22‐52 Jackson Avenue LLC, ACD Citiview Buildings, LLC, and Gerald Wolkoff (collec- tively “Wolkoff”) appeal from a judgment of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of New York (Frederic Block, J.). -

Street Art Rising Marshall Soules—[email protected]

Vol 1 No 2 (Autumn 2020) Online: jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/nexj Visit our WebBlog: newexplorations.net Street Art Rising Marshall Soules—[email protected] This illustrated article discusses the various manifestations of street art—graffiti, posters, stencils, social murals—and the impact of street art on urban environments. Continuing perceptions of street art as vandalism contributing to urban decay neglects to account for street art’s full spectrum of effects. As freedom of expression protected by law, as news from under-privileged classes, as images of social uplift and consciousness-raising, and as beautification of urban milieux, street art has social benefits requiring re-assessment. Street art has become a significant global art movement. Detailed contextual history includes the photographer Brassai's interest in Parisian graffiti between the world wars; Cézanne’s use of passage; Walter Benjamin's assemblage of fragments in The Arcades Project; the practice of dérive (passage through diverse ambiances, drifting) and détournement (rerouting, hijacking) as social and political intervention advocated by Guy Debord and the Situationist International; Dada and Surrealist montage and collage; and the art of Quebec Automatists and French Nouveaux réalistes. Present street art engages dynamically with 20th C. art history. The article explores McLuhan’s ideas about the power of mosaic style to subvert the received order, opening spaces for new discourse to emerge, new patterns to be discovered. The author compares street art to advertising, and raises questions about appropriation, authenticity, and style. How does street art survive when it leaves the streets for galleries, design shops, and museums? Street art continues to challenge communication strategies of the privileged classes and elected officials, and increasingly plays a reconstructive role in modulating the emotional tenor of urban spaces. -

Public Art, Cultural Landscapes, and Urban Space in Venice, California

The Contours of Creativity: Public Art, Cultural Landscapes, and Urban Space in Venice, California Zia Salim California State University, Fullerton Abstract This cross-sectional study examines spatial and thematic patterns of public art in Venice, Los Angeles’s bohemian beach community, to de- termine how public wall art marks the cultural landscape. To do this, 353 items of public art were field surveyed, photographed, and mapped, with the resulting inventory being subjected to content analysis. Data from secondary sources, including the city’s history and demographics, were used to contextualize the results. The results indicate that most public art is located on commercial buildings, with a smaller concentration on residential buildings. A majority of public art in Venice includes three main types of elements: local elements, people, and nature. Although public art is an especially dynamic and ephemeral subject of study, I conclude that an analysis of the locations and themes of public art helps to explain its aesthetic and historic functions and demonstrates its role in Venice’s cultural landscape. Keywords: cultural landscape, public art, street art, murals, Venice Introduction The beach community of Venice is the eclectic epicenter of Los Angeles: for decades wanderers, non-conformers, hippies, and tourists have congregated in this seaside spot to partake in Venice’s unconventional atmosphere and unique architecture. Images of the beach, the boardwalk, and the canals and their bungalows are predominant in popular imaginations of Venice’s urban geography, while popular understandings of Venice’s social geography con- sider its (counter)cultural dimensions as a haven for poets and performers, surfers and skaters, bodybuilders and bohemians, musicians and mystics, and spiritualists and free spirits. -

When the Wall Talks: a Semiotics Analysis of Graffiti Tagged by “Act Move”

When The Wall Talks: A Semiotics Analysis of Graffiti Tagged by “Act Move” A Journal Paper Hasan IbnuSafruddin (0707848) English Education Department, Faculty of Language and Arts Education, Indonesia University of Education, Dr. Setiabudhi 229, Bandung 40154, Indonesia Email: [email protected] Abstract: In Indonesia Graffiti phenomenon has become a popular culture. Graffiti exists around us; in public space, wall, and toilet.Its existence sometime lasts just a few days then beingerased, but some other exists for a long time. Some people think graffiti is a kind of vandalism, some other think it is a piece of art. That makes the graffiti interesting to me. The author believe there must be a purpose and meaning in creating graffiti. Bandung city is popular as the place of creative people; there are many communities of Bomber, graffiti creator called.The author choose some graffiti tagged by Act Move around Bandung as the sample for my analysis. Different with other graffiti, Act Move more applies more the words form rather than pictures. In this paper the author would like to analyze five graffiti tagged by Act Move around Bandung city through the Roland Barthes framework. Barthes‟ Frame work isapplied to find out the meaning of graffiti. After doing descriptive analysis of the graffiti the author also do an interview with the Bomber of Act Move to enrich the data and make the clear understanding of this study. The finding of this study is the meaning of denotation, connotation and myth or ideology of the graffiti. The author expect this study can give the exploration and interpretation the meaning beyond and surface of graffiti. -

Is Street Art Vandalism?

Large-Type Edition The University of the State of New York REGENTS HIGH SCHOOL EXAMINATION REGENTS EXAMINATION IN ENGLISH LANGUAGE ARTS Tuesday, June 12, 2018 — 9:15 a.m. to 12:15 p.m., only The possession or use of any communications device is strictly prohibited when taking this examination. If you have or use any communications device, no matter how briefly, your examination will be invalidated and no score will be calculated for you. A separate answer sheet has been provided for you. Follow the instructions for completing the student information on your answer sheet. You must also fill in the heading on each page of your essay booklet that has a space for it, and write your name at the top of each sheet of scrap paper. The examination has three parts. For Part 1, you are to read the texts and answer all 24 multiple-choice questions. For Part 2, you are to read the texts and write one source-based argument. For Part 3, you are to read the text and write a text-analysis response. The source-based argument and text-analysis response should be written in pen. Keep in mind that the language and perspectives in a text may reflect the historical and/or cultural context of the time or place in which it was written. When you have completed the examination, you must sign the statement printed at the bottom of the front of the answer sheet, indicating that you had no unlawful knowledge of the questions or answers prior to the examination and that you have neither given nor received assistance in answering any of the questions during the examination. -

Esplorare Un'estetica Nuova V. Street Art. L'arte Delle Terre Di

PierLuigi Albini 29.V – Labirinti di lettura Esplorare un’estetica nuova Street Art. L’arte delle terre di mezzo* Da qualche tempo la Street art va di moda. C’è ancora chi ancora sostiene che non si tratta di arte, mentre invece essa è una delle più fresche e originali manifestazioni artistiche del nostro tempo. Ho persino la tentazione di sostenere che essa è l’arte del nostro tempo. In questo scritto dovrò essere sintetico, nei limiti del possibile, sicché sorvolerò su molti aspetti del fenomeno, che si presenta con molte sfaccettature e, soprattutto, in continua evoluzione e ibridazione. Anzi, l’evoluzione e l’innovazione continue sono la sua condizione permanente. Forse è anche per questo che le pubblicazioni sul tema, in genere, sono più una raccolta di testimonianze e di documenti sul campo, una ricognizione analitica, che un tentativo sistematico di comprenderla in una teoria. Eppure, una certa attenzione da parte della cultura specialistica c’è stata per tempo – addirittura prima della diffusione di massa in Italia del fenomeno, se già nel 1982 il Dipartimento di Arti visive dell’Università di Bologna promosse una “Settimana internazionale sulle performances” curata da Francesca Alinovi, da Renato Barilli e da altri. Per non parlare, in seguito, delle attenzioni di Achille Bonito Oliva. Consideriamo, poi, che in Italia i Centri sociali offrirono gli spazi ai writers a partire dal 1990, promuovendo così anche la cultura hip hop. Ma da alcune testimonianze di protagonisti, sembra che solo a Bologna il rapporto degli artisti di strada con i Centri sociali non sia stato e non sia semplicemente e reciprocamente strumentale. -

Street Art Unit and Lessons

The Discovery, A Unit Plan Exploration and Manifestation of In Seven Weeks Street Art Recommended for and the First Amendment. Grades 10-12 The Pennsylvania State University School of Visual Arts, Art Education Professor Kim Powell Garrison Gunter COPYRIGHT NOTICE — SHARE OR BEWARE! — REMIX & COLLABORATE This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.5 License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 543 Howard Street, 5th Floor, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. Contents Teaching Philosophy 5 My teaching philosophy in many ways parallels my art making philoso- phy. I believe that the three common methods of teaching art today are all important components in the scaffolding of a successful education in the arts. About this Booklet 5 Unit Plan 7 Standards Met by Unit: 10 Lesson 1 / Week 1- Unit Overview 14 This first lesson will present the entire Unit’s goals to the class and provide students with a broad overview of the relevancy of street art and the value it holds in society. Guided Lessons Grading Rubric 19 GU I D E D Lessons Lesson 2 / Week 2- Sticker Art 22 The second Lesson will present the artist Shepard Fairey who is known for his Obey Giant Campaign. Lesson two’s assignment will be to bootleg the sticker project any real giant has a posse. Lesson 3 / Week 3- Stencil Art 23 Stencil art and the work of Street Artist John Tsombikos who is in- ternationally known for his BORF campaign containing an image of a friend of his who committed suicide. -

Suzanne Lacy

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Open Access Institutional Repository at Robert Gordon University LACY, S. 2013. Imperfect art: working in public; a case study of the Oakland Projects (1991-2001). PhD Thesis. Aberdeen: Robert Gordon University [online]. Available from: https://openair.rgu.ac.uk Imperfect art: working in public; a case study of the Oakland Projects (1991-2001). LACY, S. 2013 The author of this thesis retains the right to be identified as such on any occasion in which content from this thesis is referenced or re-used. The licence under which this thesis is distributed applies to the text and any original images only – re-use of any third-party content must still be cleared with the original copyright holder. This document was downloaded from https://openair.rgu.ac.uk Imperfect Art: Working in Public A Case Study of the Oakland Projects (1991–2001) Suzanne Lacy PhD. 2013 i ii IMPERFECT ART: WORKING IN PUBLIC A Case Study of the Oakland Projects (1991–2001) Suzanne Lacy A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Robert Gordon University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy This research was carried out in connection with On the Edge Research Programme, Gray’s School of Art, Robert Gordon University, Aberdeen, Scotland June 2013 iii iv IMPERFECT ART: WORKING IN PUBLIC A Case Study of the Oakland Projects (1991–2001) Suzanne Lacy Doctor of Philosophy Abstract: In Mapping the Terrain: New Genre Public Art (1994) the author called for a new language of critique for the transient and publicly located art practices known today as social, or public, practices.