Poststroke Seizure: Optimising Its Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Status Epilepticus Clinical Pathway

JOHNS HOPKINS ALL CHILDREN’S HOSPITAL Status Epilepticus Clinical Pathway 1 Johns Hopkins All Children's Hospital Status Epilepticus Clinical Pathway Table of Contents 1. Rationale 2. Background 3. Diagnosis 4. Labs 5. Radiologic Studies 6. General Management 7. Status Epilepticus Pathway 8. Pharmacologic Management 9. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring 10. Inpatient Status Admission Criteria a. Admission Pathway 11. Outcome Measures 12. References Last updated: July 7, 2019 Owners: Danielle Hirsch, MD, Emergency Medicine; Jennifer Avallone, DO, Neurology This pathway is intended as a guide for physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners and other healthcare providers. It should be adapted to the care of specific patient based on the patient’s individualized circumstances and the practitioner’s professional judgment. 2 Johns Hopkins All Children's Hospital Status Epilepticus Clinical Pathway Rationale This clinical pathway was developed by a consensus group of JHACH neurologists/epileptologists, emergency physicians, advanced practice providers, hospitalists, intensivists, nurses, and pharmacists to standardize the management of children treated for status epilepticus. The following clinical issues are addressed: ● When to evaluate for status epilepticus ● When to consider admission for further evaluation and treatment of status epilepticus ● When to consult Neurology, Hospitalists, or Critical Care Team for further management of status epilepticus ● When to obtain further neuroimaging for status epilepticus ● What ongoing therapy patients should receive for status epilepticus Background: Status epilepticus (SE) is the most common neurological emergency in children1 and has the potential to cause substantial morbidity and mortality. Incidence among children ranges from 17 to 23 per 100,000 annually.2 Prevalence is highest in pediatric patients from zero to four years of age.3 Ng3 acknowledges the most current definition of SE as a continuous seizure lasting more than five minutes or two or more distinct seizures without regaining awareness in between. -

Hitting a Wall: an Ambiguous Case of Wallenberg Syndrome

Open Access Case Report DOI: 10.7759/cureus.16268 Hitting a Wall: An Ambiguous Case of Wallenberg Syndrome James R. Pellegrini 1 , Rezwan Munshi 1 , Bohao Cao 1 , Samuel Olson 2 , Vincent Cappello 1 1. Internal Medicine, Nassau University Medical Center, East Meadow, USA 2. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, USA Corresponding author: Bohao Cao, [email protected] Abstract Wallenberg syndrome is the most common stroke of the posterior circulation. Diagnosis of Wallenberg syndrome is often overlooked as initial MRI may show no visible lesion. We present an atypical case of Wallenberg syndrome in which the initial MRI of the brain was normal. Our patient is a 65-year-old male who was brought in by emergency medical services complaining of right- sided facial droop, slurred speech, and left-sided weakness for one day. Physical examination showed decreased left arm and leg strength compared to the right side, decreased left facial temperature sensations, decreased left arm and leg temperature sensations, and difficulty sitting upright with an associated leaning towards the left side. An initial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain with and without contrast revealed no abnormality. In light of such a high suspicion for stroke based on the patient’s neurologic deficits, a repeat MRI of the brain was performed three days later and exposed a small focus of bright signal (hyperintensity) on T2-weighted fluid-attenuated inversion recovery and diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) in the left posterior medulla. Wallenberg syndrome, also known as lateral medullary syndrome or posterior inferior cerebellar artery syndrome, is a constellation of symptoms caused by posterior vascular accidents. -

Non-Epileptic Seizures a Short Guide for Patients and Families

Non-epileptic seizures a short guide for patients and families Department of Neurology Information for patients Royal Hallamshire Hospital What are non-epileptic seizures? In a seizure people lose control of their body, often causing shaking or other movements of arms and legs, blacking out, or both. Seizures can happen for different reasons. During epileptic seizures, the brain produces electrical impulses, which stop it from working normally. Non-epileptic seizures look a little like epileptic seizures, but are not caused by abnormal electrical activity in the brain. Non-epileptic seizures happen because of problems with handling thoughts, memories, emotions or sensations in the brain. Such problems are sometimes related to stress. However, they can also occur in people who seem calm and relaxed. Often people do not understand why they have developed non-epileptic seizures. Are non-epileptic seizures rare? For every 100,000 people, between 15 and 30 have non- epileptic seizures. Nearly half of all people brought in to hospital with suspected serious epilepsy turn out to have non- epileptic seizures instead. One of the reasons why you may not have heard of non- epileptic seizures is that there are several other names for the same problem. Non-epileptic seizures are also known as pseudoseizures, psychogenic, dissociative or functional seizures. Sometimes people who have non-epileptic seizures are told that they suffer from non-epileptic attack disorder (NEAD). How can I be sure that this is the right diagnosis? Non-epileptic seizures often look like epileptic seizures to friends, family members and even doctors. Like epilepsy, non- epileptic seizures can cause injuries and loss of control over bladder function. -

Acute Stroke Thrombolysis Guideline (Template) TIME IS BRAIN Call “Code Stroke” DOOR to NEEDLE TARGET IS Less Than 60 MINUTES!

Acute Stroke Thrombolysis Guideline (Template) TIME IS BRAIN Call “Code Stroke” DOOR TO NEEDLE TARGET IS less than 60 MINUTES! Guideline: Use of IV Recombinant Tissue Plasminogen Activator (rtPA, tPA, Alteplase, Actilyse®) in Acute Ischaemic Stroke This treatment is indicated in selected acute stroke patients. See New Zealand Clinical Guidelines for Stroke Management 2010 www.nzgg.org.nz Purpose This stroke thrombolysis guideline is intended to guide clinicians when planning stroke thrombolysis with intravenous tissue plasminogen activator (Alteplase). [NB: this template has been developed by the NZ National Thrombolysis Working Group, requires local adaptation, and can be used as a guideline or converted into a pathway by adding tick boxes and patient sticker areas]. Thrombolysis should be considered in patients with acute stroke symptoms arriving within 3.5 hours (treat IV within 4.5 hrs) of symptom onset. Alteplase CANNOT be substituted with any other fibrinolytic agents, including other forms of recombinant tPA. Definitions “Code Stroke” is a key component of effective thrombolysis and denotes a rapid treatment pathway to minimise onset to needle time. It is a communication protocol to activate the appropriate Stroke Thrombolysis Team to meet the patient at the hospital door. This will utilise different resources in different hospitals. It also includes: 1. Avoidance of transit to non-thrombolysis hospitals 2. Pre-hospital notification that a potential stroke thrombolysis patient is en-route with an estimated time of arrival 3. Bloods and IV lines x 2 performed in transit if no delays would result, or otherwise at hospital triage 4. Pre-notification of CT staff of pending arrival 5. -

An Atypical Presentation of Epilepsy; What a Headache! J Neurol Transl Neurosci 5(1): 1078

Central Journal of Neurology & Translational Neuroscience Bringing Excellence in Open Access Case Report Corresponding author Sarah Seyffert, Trinity School of Medicine, 505 Tadmore court Schaumburg, Illinois 60194, USA, Tel: 847-217-4262; An Atypical Presentation of Email: Submitted: 13 April 2017 Epilepsy; What a Headache! Accepted: 07 June 2017 Published: 09 June 2017 Sarah Seyffert* and Wade Kvatum ISSN: 2333-7087 Trinity School of Medicine, USA Copyright © 2017 Seyffert et al. Abstract OPEN ACCESS The relationship between headache and seizure is a poorly understood and controversial topic; however, the literature has recently suggested that the two conditions may be related. Keywords The interplay between these conditions seems to be even more complex in a group of • Epilepsy patients with epilepsy related headaches. It has been proposed that the association could • Headache be classified into preictal, ictal, postictal, or interictal headaches. Here we present a case • Ictal epileptic headache report of a 62 year old male who presented with a chief complaint of new onset severe headache and subsequently underwent multiple diagnostic testing modalities before he was finally diagnosed and treated for epilepsy, which lead to the resolution of his headache. We conclude with a short discussion of how to subcategorize seizure related headaches based on their temporal relationship and why they can pose such a difficult diagnostic challenge. ABBREVIATIONS afebrile with a normal CBC and CMP. On arrival to the hospital he underwent a non-contrast head CT scan; however, no evidence of EEG: Electroencephalogram; CBC: Complete Blood Count; acute intracranial abnormality was seen. Additionally, a lumbar CMP: Complete Metabolic Panel; CT scan: Computerized puncture was performed which was negative for xanthochromia Tomography Scan; CTA: Computed Tomographic Angiography; and showed a protein count of 27, glucose 230, and 2 white MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging blood cells. -

Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT) and Stroke Rehabilitation

Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT) and Stroke Rehabilitation Amy Quilty OT Reg. (Ont.), Occupational Therapist Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) Certificate Program, University of Toronto Quinte Health Care: [email protected] Learning Objectives • To understand that CBT: • has common ground with neuroscience • principles are consistent with stroke best practices • treats barriers to stroke recovery • is an opportunity to optimize stroke recovery Question? Why do humans dominate Earth? The power of THOUGHT • Adaptive • Functional behaviours • Health and well-being • Maladaptive • Dysfunctional behaviours • Emotional difficulties Emotional difficulties post-stroke • “PSD is a common sequelae of stroke. The occurrence of PSD has been reported as high as 30–60% of patients who have experienced a stroke within the first year after onset” Canadian Stroke Best Practice Recommendations: Mood, Cognition and Fatigue Following Stroke practice guidelines, update 2015 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ijs.12557/full • Australian rates: (Kneeborne, 2015) • Depression ~31% • Anxiety ~18% - 25% • Post Traumatic Stress ~10% - 30% • Emotional difficulties post-stroke have a negative impact on rehabilitation outcomes. Emotional difficulties post-stroke: PSD • Post stroke depression (PSD) is associated with: • Increased utilization of hospital services • Reduced participation in rehabilitation • Maladaptive thoughts • Increased physical impairment • Increased mortality Negative thoughts & depression • Negative thought associated with depression has been linked to greater mortality at 12-24 months post-stroke Nursing Best Practice Guideline from RNAO Stroke Assessment Across the Continuum of Care June : http://rnao.ca/sites/rnao- ca/files/Stroke_with_merged_supplement_sticker_2012.pdf Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0ViaCs0k2jM Cognitive Behavioral Therapy - CBT A Framework to Support CBT for Emotional Disorder After Stroke* *Figure 2, Framework for CBT after stroke. -

Seizure Triggers

SEIZURE TRIGGERS M A R I A R AQUEL LOPEZ. M.D M I A M I V H A DEFINITION OF SEIZURE VS. EPILEPSY • Epileptic seizure: Is a transient symptom of abnormal excessive electric activity of the brain. EPILEPSY • More than one epileptic seizure. TYPE OF SEIZURES ETIOLOGY • Epilepsy is a heterogeneous condition with varying etiologies including: 1. Genetic 2. Infectious 3. Trauma 4. Vascular 5. Neoplasm 6. Toxic exposures TRIGGERS FOR EPILEPTIC SEIZURES • What is a seizure trigger? It is a factor that can cause a seizure in a person who either has epilepsy or does not. • Factors that lead into a seizure are complex and it is not possible to determine the trigger in each patient. TRIGGERS A. Most common ones Stress Missing taking the medication THE MOST OFTEN REPORTED BY PATIENTS • Sleep deprivation and tiredness • Fever OTHER COMMON CAUSES . Infection . Fasting leading into hypoglycemia. Caffeine: particularly if it interrupts normal sleep patterns. Other medications like hormonal replacement, pain killers or antibiotics. OTHER TRIGGERS External precipitants • Alcohol consumption or withdrawal. *Specific triggers that are related to Reflex epilepsy Bathing Eating Reading OTHER TRIGGERS • Flashing light: especially with patients with idiopathic generalized seizure disorder STRESS . Stress is the most common patient –perceived seizure precipitant, studies of life events suggest that stressful experiences trigger seizures in certain individuals. Animals epilepsy models provide more convincing evidence that exposure to exogenous and endogenous stress mediators has been found to increase epileptic activity in the brain, especially after repeating exposure. SOLUTION ABOUT STRESS • Intervention of copying with stress STRESS MANAGEMENT • Include trying to get in a place of peace utilizing multiple techniques: • Regular exercise • Yoga and medication • Therapy or psychological support with a provider. -

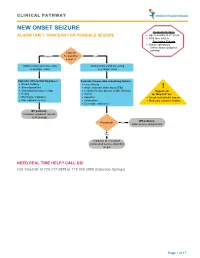

Seizure, New Onset

CLINICAL PATHWAY NEW ONSET SEIZURE Inclusion Criteria ALGORITHM 1. CONCERN FOR POSSIBLE SEIZURE • Age 6 months to 21 years • First-time seizure Exclusion Criteria • Status epilepticus (refer to status epilepticus pathway) Concern Unsure for possible Yes seizure? Obtain history and screening Obtain history and screening neurologic exam neurologic exam Consider differential diagnoses: Evaluate for possible provoking factors: • Breath holding • Fever/illness • Stereotypies/tics • Acute traumatic brain injury (TBI) ! • Vasovagal/syncope/vertigo • Central nervous system (CNS) infection Urgent call • Reflux • Tumor to ‘OneCall’ for: • Electrolyte imbalance • Ingestion • Suspected infantile spasm • Non epileptic seizure • Intoxication • Medically complex children • Electrolyte imbalance Off pathway: Consider outpatient referral to Neurology Off pathway: Provoked? Yes Address provoking factors No Continue to new onset unprovoked seizure algorithm on p.2 NEED REAL TIME HELP? CALL US! Call ‘OneCall’ at 720-777-3999 or 719-305-3999 (Colorado Springs) Page 1 of 17 CLINICAL PATHWAY ALGORITHM 2. NEW ONSET UNPROVOKED SEIZURE Inclusion Criteria • Age 6 months to 21 years New onset unprovoked • First-time unprovoked seizure seizure • Newly recognized seizure or epilepsy syndrome Exclusion Criteria • Provoked seizure: any seizure as a symptom of fever/illness, acute traumatic brain injury (TBI), Has central nervous system (CNS) infection, tumor, patient returned ingestion, intoxication, or electrolyte imbalance Consult inpatient • to baseline within No -

SWOSS Prevention Committee

Hemiplegic Shoulder Power Point for staff education sessions Presented by Cathy McBay and Candace Coe HHS Stroke Annual Review March 7 and 7, 2018 www.swostroke.ca Overview • Structure of the Shoulder Complex • Low Tone Upper Limb • Hemi Arm protocol • High Tone Upper Limb • Hemiplegic Shoulder Pain Hemi Sling Application Structure GLENOHUMERAL JOINT • Ball and socket joint. • Stability sacrificed for mobility. MUSCULAR CONTROL • Rotator Cuff muscles • Scapular and trunk muscles Biomechanics: Arm Elevation • 0-90 degrees • Primarily arm (ie:humerus) movement • Little movement in shoulder blade (scapula) • Above 90 degrees • To allow normal movement and prevent impingement of rotator cuff tendons the shoulder blade MUST o Rotate up o Glide along rib cage Low Tone Shoulder • Most common in initial stages following stroke. • Results from damage to the motor pathways innervating the upper limb muscles. • Low tone shoulders are highly susceptible to damage of the structures surrounding the shoulder (muscles, tendons, ligaments). • Preventing subluxation is crucial in the early stages of stroke recovery- critical role for all team members Low Tone Shoulder • Pathoanatomy of Subluxed Shoulder • Flaccid or low tone muscles at shoulder and trunk lead to altered alignment of scapula and humerus. • Stabilizing muscles not present • Muscles overstretch due to weight of arm in dependent position. • Inferior subluxation is most common Shoulder Subluxation • Consequences of shoulder subluxation: • Irreversible stretching of ligaments, tendons and capsule leading to instability at the joint. • Structural changes hamper recovery of muscle activity in shoulder complex. • Injury to brachial plexus. • Chronic shoulder pain. Shoulder Subluxation Management of Low Tone Shoulder • Positioning • Support low tone arm at all times: o Use pillows, slings, lap trays o Slings should be worn during transfers or ambulation only. -

Epilepsy After Stroke

Stroke Helpline: 0303 3033 100 Website: stroke.org.uk Epilepsy after stroke In the first few weeks after a stroke some people have a seizure, and a small number go on to develop epilepsy – a tendency to have repeated seizures. These can usually be completely controlled with treatment. This factsheet explains what epilepsy is, the different types of seizures, and how epilepsy is diagnosed and treated. It also includes advice about coping with a seizure, and a glossary. Epilepsy is a tendency to have repeated What causes seizures? seizures – sometimes called ‘fits’ or ‘attacks’. It affects just under one per cent Cells in the brain communicate with one of people in the UK. Stroke is one of many another and with our muscles by passing conditions that can lead to epilepsy. electrical signals along nerve fibres. If you have epilepsy this electrical activity can Around five per cent of people who have a become disordered. A sudden abnormal stroke will have a seizure within the following burst of electrical activity in the brain can few weeks. These are known as acute or lead to a seizure. onset seizures and normally happen within 24 hours of the stroke. You are more likely There are over 40 different types of seizures to have one if you have had a severe stroke, ranging from tingling sensations or ‘going a stroke caused by bleeding in the brain (a blank’ for a few seconds, to shaking and haemorrhagic stroke), or a stroke involving losing consciousness. the part of the brain called the cerebral cortex. If you have an onset seizure, it This can mean that epilepsy is sometimes does not necessarily mean you have or will confused with other conditions, including develop epilepsy. -

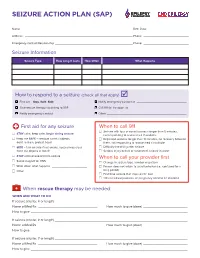

Seizure Action Plan (Sap)

SEIZURE ACTION PLAN (SAP) Name: ——————————————————————————————————————————————————— Birth Date: ——————————————————— Address: —————————————————————————————————————————————————— Phone: ————————————————————— Emergency Contact/Relationship ———————————————————————————————————— Phone: ————————————————————— Seizure Information Seizure Type How Long It Lasts How Often What Happens How to respond to a seizure (check all that apply) F First aid – Stay. Safe. Side. F Notify emergency contact at ______________________________ F Give rescue therapy according to SAP F Call 911 for transport to __________________________________________ F Notify emergency contact F Other ________________________________________________ First aid for any seizure When to call 911 F Seizure with loss of consciousness longer than 5 minutes, F STAY calm, keep calm, begin timing seizure not responding to rescue med if available F Keep me SAFE – remove harmful objects, F Repeated seizures longer than 10 minutes, no recovery between don’t restrain, protect head them, not responding to rescue med if available F SIDE – turn on side if not awake, keep airway clear, F Difficulty breathing after seizure don’t put objects in mouth F Serious injury occurs or suspected, seizure in water F STAY until recovered from seizure When to call your provider first F Swipe magnet for VNS F Change in seizure type, number or pattern F Write down what happens _____________________ F Person does not return to usual behavior (i.e., confused for a F Other _____________________________________ long -

Psychotic Disorder Due to Lafora Disease: a Case Report

2015 iMedPub Journals Clinical Psychiatry http://www.imedpub.com Vol. 1 No. 1:2 Psychotic Disorder Due to Lafora Şafak Taktak1 , 2 Disease: A Case Report Mustafa Karakuş 1 Psychiatry Department, Ahi Evran University Education and Research Hospital, Turkey 2 Forensic Medicine and Emergency Medicine Department, Yenimahalle Abstract Education and Research Hospital, Turkey Lafora disease is a type of progressive myoclonic epilepsy with poor prognosis, characterized by myoclonus, seizures, cerebellar ataxia and mental disorder. Lafora disease frequently develops at 10-18 years of age and tranmission is autosomal recessive. The first symptoms are usually Corresponding author: Şafak Taktak myoclonic, tonic-clonic, atonic or absence seizures. Epilepsy in children and adolescents with depression, anxiety disorders, attention deficit Psychiatry Department, Ahi Evran hyperactivity disorder can be seen relatively frequently. More rarely, these University Education and Research people can be seen in psychotic disorders. In this paper, we aimed to draw Hospital, Turkey attention to diagnosis of fatal, resistance to treatment with serious suicide attempt and diagnosis of Lafora developing psychotic symptoms in children. [email protected] Tel: 05054037967 Introduction from effective treatment and resulting in death was reported , as Epilepsy in childhood, with prevalence 0,5-1 %, are among the a case report [1-11]. most common neurological diagnosis. Progressive myoclonic constitutes less than 1% of all epilepsies, while Lafora disease Case constitutes 10% of all epilepsies. Lafora disease is a type of progressive myoclonic epilepsy with poor prognosis, characterized The index case, a 12-year-old girl, who had a family history of by myoclonus, seizures, cerebellar ataxia and mental disorder.