Venom of the Red-Bellied Black Snake Pseudechis Porphyriacus Shows Immunosuppressive Potential

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phylogeny of the Black Snakes (Pseudechis: Elapidae: Serpentes

1 Multi-locus phylogeny and species delimitation of Australo-Papuan blacksnakes 2 (Pseudechis Wagler, 1830: Elapidae: Serpentes) 3 4 Simon T. Maddock 1,2,3,4,*, Aaron Childerstone 3, Bryan Grieg Fry 5, David J. Williams 5 6,7, Axel Barlow 3,8, Wolfgang Wüster 3 6 7 1 Department of Life Sciences, The Natural History Museum, London, SW7 5BD, UK. 8 2 Department of Genetics, Evolution and Environment, University College London, 9 London, WC1E 6BT, UK. 10 3 School of Biological Sciences, Environment Centre Wales, Bangor University, Bangor, 11 LL57 2UW, United Kingdom. 12 4 Department of Animal Management, Reaseheath, College, Nantwich, Cheshire, CW5 13 6DF, UK. 14 5 Venom Evolution Lab, School of Biological Sciences, University of Queensland, St 15 Lucia QLD, 4072 Australia. 16 6 Australian Venom Research Unit, Department of Pharmacology, University of 17 Melbourne, Parkville, Vic, 3010, Australia. 18 7 School of Medicine & Health Sciences, University of Papua New Guinea, Boroko, 19 NCD, 121, Papua New Guinea. 20 8 Institute for Biochemistry and Biology, University of Potsdam, 14476 Potsdam (Golm), 21 Germany. 22 23 * corresponding author: [email protected] 24 25 Abstract 26 Genetic analyses of Australasian organisms have resulted in the identification of 27 extensive cryptic diversity across the continent. The venomous elapid snakes are among 28 the best-studied organismal groups in this region, but many knowledge gaps persist: for 29 instance, despite their iconic status, the species-level diversity among Australo-Papuan 30 blacksnakes (Pseudechis) has remained poorly understood due to the existence of a group 31 of cryptic species within the P. -

Neurotoxic Effects of Venoms from Seven Species of Australasian Black Snakes (Pseudechis): Efficacy of Black and Tiger Snake Antivenoms

Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology and Physiology (2005) 32, 7–12 NEUROTOXIC EFFECTS OF VENOMS FROM SEVEN SPECIES OF AUSTRALASIAN BLACK SNAKES (PSEUDECHIS): EFFICACY OF BLACK AND TIGER SNAKE ANTIVENOMS Sharmaine Ramasamy,* Bryan G Fry† and Wayne C Hodgson* *Monash Venom Group, Department of Pharmacology, Monash University, Clayton and †Australian Venom Research Unit, Department of Pharmacology, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria, Australia SUMMARY the sole clad of venomous snakes capable of inflicting bites of medical importance in the region.1–3 The Pseudechis genus (black 1. Pseudechis species (black snakes) are among the most snakes) is one of the most widespread, occupying temperate, widespread venomous snakes in Australia. Despite this, very desert and tropical habitats and ranging in size from 1 to 3 m. little is known about the potency of their venoms or the efficacy Pseudechis australis is one of the largest venomous snakes found of the antivenoms used to treat systemic envenomation by these in Australia and is responsible for the vast majority of black snake snakes. The present study investigated the in vitro neurotoxicity envenomations. As such, the venom of P. australis has been the of venoms from seven Australasian Pseudechis species and most extensively studied and is used in the production of black determined the efficacy of black and tiger snake antivenoms snake antivenom. It has been documented that a number of other against this activity. Pseudechis from the Australasian region can cause lethal 2. All venoms (10 g/mL) significantly inhibited indirect envenomation.4 twitches of the chick biventer cervicis nerve–muscle prepar- The envenomation syndrome produced by Pseudechis species ation and responses to exogenous acetylcholine (ACh; varies across the genus and is difficult to characterize because the 1 mmol/L), but not to KCl (40 mmol/L), indicating activity at offending snake is often not identified.3,5 However, symptoms of post-synaptic nicotinic receptors on the skeletal muscle. -

Broad-Headed Snake (Hoplocephalus Bungaroides)', Proceedings of the Royal Zoological Society of New South Wales (1946-7), Pp

Husbandry Guidelines Broad-Headed Snake Hoplocephalus bungaroides Compiler – Charles Morris Western Sydney Institute of TAFE, Richmond Captive Animals Certificate III RUV3020R Lecturers: Graeme Phipps, Jacki Salkeld & Brad Walker 2009 1 Occupational Health and Safety WARNING This Snake is DANGEROUSLY VENOMOUS CAPABLE OF INFLICTING A POTENTIALLY FATAL BITE ALWAYS HAVE A COMPRESSION BANDAGE WITHIN REACH SNAKE BITE TREATMENT: Do NOT wash the wound. Do NOT cut the wound, apply substances to the wound or use a tourniquet. Do NOT remove jeans or shirt as any movement will assist the venom to enter the blood stream. KEEP THE VICTIM STILL. 1. Apply a broad pressure bandage over the bite site as soon as possible. 2. Keep the limb still. The bandage should be as tight as you would bind a sprained ankle. 3. Extend the bandage down to the fingers or toes then up the leg as high as possible. (For a bite on the hand or forearm bind up to the elbow). 4. Apply a splint if possible, to immobilise the limb. 5. Bind it firmly to as much of the limb as possible. (Use a sling for an arm injury). Bring transport to the victim where possible or carry them to transportation. Transport the victim to the nearest hospital. Please Print this page off and put it up on the wall in your snake room. 2 There is some serious occupational health risks involved in keeping venomous snakes. All risk can be eliminated if kept clean and in the correct lockable enclosures with only the risk of handling left in play. -

Herpetological Review

Herpetological Review Volume 41, Number 2 — June 2010 SSAR Offi cers (2010) HERPETOLOGICAL REVIEW President The Quarterly News-Journal of the Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles BRIAN CROTHER Department of Biological Sciences Editor Southeastern Louisiana University ROBERT W. HANSEN Hammond, Louisiana 70402, USA 16333 Deer Path Lane e-mail: [email protected] Clovis, California 93619-9735, USA [email protected] President-elect JOSEPH MENDLELSON, III Zoo Atlanta, 800 Cherokee Avenue, SE Associate Editors Atlanta, Georgia 30315, USA e-mail: [email protected] ROBERT E. ESPINOZA KERRY GRIFFIS-KYLE DEANNA H. OLSON California State University, Northridge Texas Tech University USDA Forestry Science Lab Secretary MARION R. PREEST ROBERT N. REED MICHAEL S. GRACE PETER V. LINDEMAN USGS Fort Collins Science Center Florida Institute of Technology Edinboro University Joint Science Department The Claremont Colleges EMILY N. TAYLOR GUNTHER KÖHLER JESSE L. BRUNNER Claremont, California 91711, USA California Polytechnic State University Forschungsinstitut und State University of New York at e-mail: [email protected] Naturmuseum Senckenberg Syracuse MICHAEL F. BENARD Treasurer Case Western Reserve University KIRSTEN E. NICHOLSON Department of Biology, Brooks 217 Section Editors Central Michigan University Mt. Pleasant, Michigan 48859, USA Book Reviews Current Research Current Research e-mail: [email protected] AARON M. BAUER JOSHUA M. HALE BEN LOWE Department of Biology Department of Sciences Department of EEB Publications Secretary Villanova University MuseumVictoria, GPO Box 666 University of Minnesota BRECK BARTHOLOMEW Villanova, Pennsylvania 19085, USA Melbourne, Victoria 3001, Australia St Paul, Minnesota 55108, USA P.O. Box 58517 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Salt Lake City, Utah 84158, USA e-mail: [email protected] Geographic Distribution Geographic Distribution Geographic Distribution Immediate Past President ALAN M. -

Venemous Snakes

WASAH WESTERN AUSTRALIAN SOCIETY of AMATEUR HERPETOLOGISTS (Inc) K E E P I N G A D V I C E S H E E T Venomous Snakes Southern Death Adder (Acanthophis Southern Death antarcticus) – Maximum length 100 cm. Adder Category 5. Desert Death Adder (Acanthophis pyrrhus) – Acanthophis antarcticus Maximum length 75 cm. Category 5. Pilbara Death Adder (Acanthophis wellsi) – Maximum length 70 cm. Category 5. Western Tiger Snake (Notechis scutatus) - Maximum length 160 cm. Category 5. Mulga Snake (Pseudechis australis) – Maximum length 300 cm. Category 5. Spotted Mulga Snake (Pseudechis butleri) – Maximum length 180 cm. Category 5. Dugite (Pseudonaja affinis affinis) – Maximum Desert Death Adder length 180 cm. Category 5. Acanthophis pyrrhus Gwardar (Pseudonaja nuchalis) – Maximum length 100 cm. Category 5. NOTE: All species listed here are dangerously venomous and are listed as Category 5. Only the experienced herpetoculturalist should consider keeping any of them. One must be over 18 years of age to hold a category 5 license. Maintaining a large elapid carries with 1 it a considerable responsibility. Unless you are Pilbara Death Adder confident that you can comply with all your obligations and licence requirements when Acanthophis wellsi keeping dangerous animals, then look to obtaining a non-venomous species instead. NATURAL HABITS: Venomous snakes occur in a wide variety of habitats and, apart from death adders, are highly mobile. All species are active day and night. HOUSING: In all species listed except death adders, one adult (to 150 cm total length) can be kept indoors in a lockable, top-ventilated, all glass or glass-fronted wooden vivarium of Western Tiger Snake at least 90 x 45 cm floor area. -

An Investigation of the Evolution of Australian Elapid Snake Venoms

toxins Article Rapid Radiations and the Race to Redundancy: An Investigation of the Evolution of Australian Elapid Snake Venoms Timothy N. W. Jackson 1, Ivan Koludarov 1, Syed A. Ali 1,2, James Dobson 1, Christina N. Zdenek 1, Daniel Dashevsky 1, Bianca op den Brouw 1, Paul P. Masci 3, Amanda Nouwens 4, Peter Josh 4, Jonathan Goldenberg 1, Vittoria Cipriani 1, Chris Hay 1, Iwan Hendrikx 1, Nathan Dunstan 5, Luke Allen 5 and Bryan G. Fry 1,* 1 Venom Evolution Lab, School of Biological Sciences, University of Queensland, St Lucia, QLD 4072, Australia; [email protected] (T.N.W.J.); [email protected] (I.K.); [email protected] (S.A.A.); [email protected] (J.D.); [email protected] (C.N.Z.); [email protected] (D.D.); [email protected] (B.o.d.B.); [email protected] (J.G.); [email protected] (V.C.); [email protected] (C.H.); [email protected] (I.H.) 2 HEJ Research Institute of Chemistry, International Centre for Chemical and Biological Sciences (ICCBS), University of Karachi, Karachi 75270, Pakistan 3 Princess Alexandra Hospital, Translational Research Institute, University of Queensland, St Lucia, QLD 4072, Australia; [email protected] 4 School of Chemistry and Molecular Biosciences, University of Queensland, St Lucia, QLD 4072, Australia; [email protected] (A.N.); [email protected] (P.J.) 5 Venom Supplies, Tanunda, South Australia 5352, Australia; [email protected] (N.D.); [email protected] (L.A.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +61-4-0019-3182 Academic Editor: Nicholas R. -

A Taxonomic Framework for Typhlopid Snakes from the Caribbean and Other Regions (Reptilia, Squamata)

caribbean herpetology article A taxonomic framework for typhlopid snakes from the Caribbean and other regions (Reptilia, Squamata) S. Blair Hedges1,*, Angela B. Marion1, Kelly M. Lipp1,2, Julie Marin3,4, and Nicolas Vidal3 1Department of Biology, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802-5301, USA. 2Current address: School of Dentistry, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7450, USA. 3Département Systématique et Evolution, UMR 7138, C.P. 26, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, 57 rue Cuvier, F-75231 Paris cedex 05, France. 4Current address: Department of Biology, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802-5301 USA. *Corresponding author ([email protected]) Article registration: http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:47191405-862B-4FB6-8A28-29AB7E25FBDD Edited by: Robert W. Henderson. Date of publication: 17 January 2014. Citation: Hedges SB, Marion AB, Lipp KM, Marin J, Vidal N. 2014. A taxonomic framework for typhlopid snakes from the Caribbean and other regions (Reptilia, Squamata). Caribbean Herpetology 49:1–61. Abstract The evolutionary history and taxonomy of worm-like snakes (scolecophidians) continues to be refined as new molec- ular data are gathered and analyzed. Here we present additional evidence on the phylogeny of these snakes, from morphological data and 489 new DNA sequences, and propose a new taxonomic framework for the family Typhlopi- dae. Of 257 named species of typhlopid snakes, 92 are now placed in molecular phylogenies along with 60 addition- al species yet to be described. Afrotyphlopinae subfam. nov. is distributed almost exclusively in sub-Saharan Africa and contains three genera: Afrotyphlops, Letheobia, and Rhinotyphlops. Asiatyphlopinae subfam. nov. is distributed in Asia, Australasia, and islands of the western and southern Pacific, and includes ten genera:Acutotyphlops, Anilios, Asiatyphlops gen. -

Frogs & Reptiles NE Vic 2018 Online

Reptiles and Frogs of North East Victoria An Identication and Conservation Guide Victorian Conservation Status (DELWP Advisory List) cr critically endangered en endangered Reptiles & Frogs vu vulnerable nt near threatened dd data deficient L Listed under the Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act (FFG, 1988) Size: of North East Victoria Lizards, Dragons & Skinks: Snout-vent length (cm) Snakes, Goannas: Total length (cm) An Identification and Conservation Guide Lowland Copperhead Highland Copperhead Carpet Python Gray's Blind Snake Nobbi Dragon Bearded Dragon Ragged Snake-eyed Skink Large Striped Skink Frogs: Snout-vent length male - M (mm) Snout-vent length female - F (mm) Austrelaps superbus 170 (NC) Austrelaps ramsayi 115 (PR) Morelia spilota metcalfei – en L 240 (DM) Ramphotyphlops nigrescens 38 (PR) Diporiphora nobbi 8.4 (PR) Pogona barbata – vu 25 (DM) Cryptoblepharus pannosus Snout-Vent 3.5 (DM) Ctenotus robustus Snout-Vent 12 (DM) Guide to symbols Venomous Lifeform F Fossorial (burrows underground) T Terrestrial Reptiles & Frogs SA Semi Arboreal R Rock-dwelling Habitat Type Alpine Bog Montane Forests Alpine Grassland/Woodland Lowland Grassland/Woodland White-lipped Snake Tiger Snake Woodland Blind Snake Olive Legless Lizard Mountain Dragon Marbled Gecko Copper-tailed Skink Alpine She-oak Skink Drysdalia coronoides 40 (PR) Notechis scutatus 200 (NC) Ramphotyphlops proximus – nt 50 (DM) Delma inornata 13 (DM) Rankinia diemensis Snout-Vent 7.5 (NC) Christinus marmoratus Snout-Vent 7 (PR) Ctenotus taeniolatus Snout-Vent 8 (DM) Cyclodomorphus praealtus -

Australian Society of Herpetologists

1 THE AUSTRALIAN SOCIETY OF HERPETOLOGISTS INCORPORATED NEWSLETTER 48 Published 29 October 2014 2 Letter from the editor This letter finds itself far removed from last year’s ASH conference, held in Point Wolstoncroft, New South Wales. Run by Frank Lemckert and Michael Mahony and their team of froglab strong, the conference featured some new additions including the hospitality suite (as inspired by the Turtle Survival Alliance conference in Tuscon, Arizona though sadly lacking of the naked basketball), egg and goon race and bouncing castle (Simon’s was a deprived childhood), as well as the more traditional elements of ASH such as the cricket match and Glenn Shea’s trivia quiz. May I just add that Glenn Shea wowed everyone with his delightful skin tight, anatomically correct, and multi-coloured, leggings! To the joy of everybody in the world, the conference was opened by our very own Hal Cogger (I love you Hal). Plenary speeches were given by Dale Roberts, Lin Schwarzkopf and Gordon Grigg and concurrent sessions were run about all that is cutting edge in science and herpetology. Of note, award winning speeches were given by Kate Hodges (Ph.D) and Grant Webster (Honours) and the poster prize was awarded to Claire Treilibs. Thank you to everyone who contributed towards an update and Jacquie Herbert for all the fantastic photos. By now I trust you are all preparing for the fast approaching ASH 2014, the 50 year reunion and set to have many treats in store. I am sad to not be able to join you all in celebrating what is sure to be, an informative and fun spectacle. -

Prohibited and Regulated Animals List

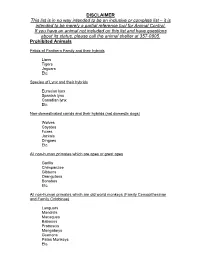

DISCLAIMER This list is in no way intended to be an inclusive or complete list – it is intended to be merely a partial reference tool for Animal Control. If you have an animal not included on this list and have questions about its status, please call the animal shelter at 357-0805. Prohibited Animals Felids of Panthera Family and their hybrids Lions Tigers Jaguars Etc. Species of Lynx and their hybrids Eurasian lynx Spanish lynx Canadian lynx Etc. Non-domesticated canids and their hybrids (not domestic dogs) Wolves Coyotes Foxes Jackals Dingoes Etc. All non-human primates which are apes or great apes Gorilla Chimpanzee Gibbons Orangutans Bonobos Etc. All non-human primates which are old world monkeys (Family Cercopithecinae and Family Colobinae) Languars Mandrills Macaques Baboons Proboscis Mangabeys Guenons Patas Monkeys Etc. Prohibited Animals Continued: Other included animals Polar Bears Grizzly Bears Elephants Rhinoceroses Hippopotamuses Komodo Dragons Water Monitors Crocodile Monitors Members of the Crocodile Family African Rock Pythons Burmese Pythons Reticulated Pythons Anacondas All Venomous Reptiles – see attached list Venomous Reptiles Family Viperidae Family Elapidae mountain bush viper death adders Barbour’s short headed viper shieldnose cobras bush vipers collared adders jumping pit vipers water cobras Fea’s vipers Indian kraits adders and puff adders dwarf crowned snakes palm pit vipers Oriental coral snakes forest pit vipers venomous whip snakes lanceheads mambas Malayan pit vipers ornamental snakes Night adders Australian -

Very Venomous, But...- Snakes of the Wet Tropics

No.80 January 2004 Notes from Very venomous but ... the Australia is home to some of the most venomous snakes in the world. Why? Editor It is possible that strong venom may little chance to fight back. There are six main snake families have evolved chiefly as a self-defence in Australia – elapids (venomous strategy. It is interesting to look at the While coastal and inland taipans eat snakes, the largest group), habits of different venomous snakes. only mammals, other venomous colubrids (‘harmless’ snakes) Some, such as the coastal taipan snakes feed largely on reptiles and pythons, blindsnakes, filesnakes (Oxyuranus scutellatus), bite their frogs. Venom acts slowly on these and seasnakes. prey quickly, delivering a large amount ‘cold-blooded’ creatures with slow of venom, and then let go. The strong metabolic rates, so perhaps it needs to Australia is the only continent venom means that the prey doesn’t be especially strong. In addition, as where venomous snakes (70 get far before succumbing so the many prey species develop a degree of percent) outnumber non- snake is able to follow at a safe immunity to snake venom, a form of venomous ones. Despite this, as distance. Taipans eat only mammals – evolutionary arms race may have been the graph on page one illustrates, which are able to bite back, viciously. taking place. very few deaths result from snake This strategy therefore allows the bites. It is estimated that between snake to avoid injury. … not necessarily deadly 50 000 and 60 000 people die of On the other hand, the most Some Australian snakes may be snake bite each year around the particularly venomous, but they are world. -

Comparative Studies of the Venom of a New Taipan Species, Oxyuranus Temporalis, with Other Members of Its Genus

Toxins 2014, 6, 1979-1995; doi:10.3390/toxins6071979 OPEN ACCESS toxins ISSN 2072-6651 www.mdpi.com/journal/toxins Article Comparative Studies of the Venom of a New Taipan Species, Oxyuranus temporalis, with Other Members of Its Genus Carmel M. Barber 1, Frank Madaras 2, Richard K. Turnbull 3, Terry Morley 4, Nathan Dunstan 5, Luke Allen 5, Tim Kuchel 3, Peter Mirtschin 2 and Wayne C. Hodgson 1,* 1 Monash Venom Group, Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, Monash University, Clayton, Victoria 3168, Australia; E-Mail: [email protected] 2 Venom Science Pty Ltd, Tanunda, South Australia 5352, Australia; E-Mails: [email protected] (F.M.); [email protected] (P.M.) 3 SA Pathology, IMVS Veterinary Services, Gilles Plains, South Australia 5086, Australia; E-Mails: [email protected] (R.K.T.); [email protected] (T.K.) 4 Adelaide Zoo, Adelaide, South Australia 5000, Australia; E-Mail: [email protected] 5 Venom Supplies, Tanunda, South Australia, South Australia 5352, Australia; E-Mails: [email protected] (N.D.); [email protected] (L.A.) * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +61-3-9905-4861; Fax: +61-3-9905-2547. Received: 5 May 2014; in revised form: 11 June 2014 / Accepted: 16 June 2014 / Published: 2 July 2014 Abstract: Taipans are highly venomous Australo-Papuan elapids. A new species of taipan, the Western Desert Taipan (Oxyuranus temporalis), has been discovered with two specimens housed in captivity at the Adelaide Zoo. This study is the first investigation of O.