Digital Locks and the Automation of Virtue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Historyof Locks

Master Locksmiths Association History of Locks Museum Part II - Catalogue of Exhibits This section is in artefact numerical order to facilitate quickly KEY TO ABREVIATIONS finding the relevant notes to items on display. There is also an Art No. Artefact number Class main classification alphabetical index at the end of this section CoR: country or region FDL: found date & location FM- Fordingbridge Museum We hope you enjoy the selections featured here. You are Hz: hazards welcome to mark up the records (pencils provided) with KID keeper ID number Loc location missing or additional information for inclusion in future MLA-HR MLA- Heritage Room reprints/editions. The artefacts on display are periodically Mt: materials PFC- formally: Peter Frima Collection changed or updated; this also corresponds with a new edition Ref No. former ID number(s) of this book. We also welcome your artefact/document Sn: serial number Sz: size donations to feature in future displays either here in the MLA THC- The Heritage Collection Heritage Lock Room or the History of Locks Museum Lock Wt: weight Rooms and Archive, more information from: [email protected] Class/Title: Date: c – Art No: Serial number: Country or Region: y m d – Group /KID Maker or Brand Image thumbnail Size: Materials: Weight: Hazards: FdL: Found date/location period – /Loc /Ref No. Description/Notes/Provenance. style - 006 Hobbs Key: Parautoptic, 6 levers. 19th century THC- /1947 CoR: England. 1860’s MLA- Sz: 135mm. Mt: steel. Wt: 96g. HR9/2 Bankers Changeable 6 lever key with both adjustable steps and removable bit. 011 Price, George Lock: Cut cabinet. -

Non -Destructive Entry Magazine

#3#3 Non-Destructive Entry Magazine Medecoder ABUS Plus Ingersoll Tiger Team And More! MayMay FOR LOCKSPORT! 20082008 WelcomeWelcome For Locksport! I received a message the other night. It was Amanda, a friend of mine who has recently taken up lockpicking. She was complaining that the challenge lock I left at her house had pricked her with a metal splinter. I told her I was sorry, she simply replied: “I HAVE BLED FOR LOCKSPORT!” I have too actually, when I first tried to make my own picks. In fact, in an informal survey I found that 100% of NDE readers who were surveyed have bled for locksport. A staggering percentage! We give our blood to these locks and it’s worth remembering what they give to us. Locks provide us not just with physical safety, but with peace of mind. They are a staple of the civilized world. A lock says “someone owns this, it’s not for you.” It’s the dividing line between the public and the private. And for the lockpicker? A lock presents a chal- lenge, a never-ending supply of new puzzles and as our hobby grows. Fueled as every- thing is now, by the internet, we see more collaboration, faster progress and ever more clever solutions to the problems the locks pose. However, there are new challenges that we should have seen coming. Specifically, how to disclose this information. The trouble is, when we get excited at our discovery and bound off to tell as many people as we can, we are celebrating what a lock means for us, it’s been conquered, the puzzle solved, the code deciphered. -

The Lock Collector from Tony Beck January/March 2006 Issue No

The Lock Collector From Tony Beck January/March 2006 Issue No. 10 All Ri ghts Reserved. Copyright ©, R. A. Beck 2006. Editor’s Note: This issue extends the miserly single page biography of Edwin C otterill included in the last one! He stands highly amongst the greatest English lock inventors, particularly for his Climax Det ector lock patented in 1846. This issue contains Part 2: His Middle Age and Lock Inventions. The final Part 3 will follow next i ssue. Most of us will know of Willenhall Lock Museum’s demise and transformation to The Locksmith’s House. All this involved co nsiderable change when the Black Country Living Museum became the new owners in May 2003. Richard Hopkins, who helped them to de al with the complexities of cataloguing the Locks, Keys and Archive material, has kindly contributed an article setting out what was involved. I do hope it will be found interesting, and perhaps some questions will arise. Like - will an Inventory of all the locks, keys and archives be sometime available to view? Does the Museum intend to consult with lock collectors on what items are to be exhibited in the Locksmith’s House apart from those initially on show? Also what plans are there to introduce the Museum’s exhibits held in BCLM’s Dudley store to public view? It’s certainly sad to see the opportunity lost that might have seen finance being provided to expand and create a fine Museum dedicated to locks and keys; like there is in Austria, France, German y, Holland, U.S.A., etc. -

Keying Systems and Nomenclature

KEYING SYSTEMS AND NOMENCLATURE Keying Procedures, Systems, and and the authors of the previous FOREWORD Nomenclature was first published in editions should take pride in the 1965, revised in 1969, 1975 and again results. in 1978. It introduced a procedural There are still some misapplications system of keying terminology radically and misunderstandings of the system different from that commonly used and it is the purpose of this edition to prior to 1965. The need for standard clarify the system to avoid terminology was clear but the misunderstanding. With this in mind, acceptance of the new system was text and format changes have been slow. made with the aim of introducing Manufacturers, Distributors, Building criteria in their order of complexity, to Owners, and Operators were make the manual an even better frustrated over the use of various and instructional tool for those progressing differing terms. Among those using the through basic, intermediate, and terms, different meanings and advanced study of the subject. interpretations were applied. As a Since the manual does not cover result, errors were made, and frequent actual keying procedures, the title of correspondence occurred between the manual has been changed. For manufacturers and distributors, those interested in the actual seeking clarification. The consumer techniques of keying or the sometimes had a sketchy mathematics of setting up a key understanding of the key system he system, many fine books and had purchased. publications are offered by the lock- Since its inception, the procedures smithing industry. outlined in this manual have been taught at the DHI Technical Programs Robert Perry, AHC/CDC John R. -

2340-002-ASSA ABLOY Key Control Design Guide

Key Control Design Guide Increase the Safety and Security of Your Facility A security solution from ASSA ABLOY Group brands: CORBIN RUSSWIN | MEDECO | SARGENT | YALE Contents I. Introduction . 2 II. Recommended Companion Document . 3 III. Comprehensive Model Key Control Policy a. Purpose. 4 b. Specification. 5 c. Enforcement . 6 d. Elements of a Key Control Policy . 7 Key Control Authority (KCA). 7 Storage. 7 Key Management Formats . 8 Record Keeping . 10 Policies and Procedures . 10 1. Identifying Keys and Keying 2. Issuing Keys 3. Returning Keys 4. Non-returned key policy 5. Administration of the Master Key System 6. Audits 7. Transfer/Temporary use Forms. 13 Servicing . 15 IV. Condensed Model Key Control Policy . 16 V. Specific Applications: a. Educational K-12. 18 b. Healthcare Facilities . 19 c. Colleges and Universities . 21 d. Office Buildings. 22 VI. Glossary of Terms and Definitions. 23 © ASSA ABLOY SALES & MARKETING GROUP INC. 2005, 2006, 2007. All rights reserved. 3 Introduction This “Key Control Design Guide” is brought to you by ASSA ABLOY, the world’s leading group of manufacturers and suppliers of locking solutions, dedicated to satisfying end-users’ needs for security and safety. Providing key systems and associated hardware is only the beginning. For end-users to successfully enjoy the benefits of the products we furnish, and to extend the life and value of a key system, proper policies must be in place. The policies and procedures suggested in this manual can play an essential part in increasing the safety and security of any facility. This manual should be used as a model or guide only. -

September/October 2010 Issu E 24 – $14.00 TILJ Janfeb10:TILJ 1/20/10 12:38 PM Page 2

The I nde pe nd en t September/October 2010 L Issue 24 – $14.00 o c k s m i t h h h J J J o o o u u u r r r n n n a a a l l l TILJ_JanFeb10:TILJ 1/20/10 12:38 PM Page 2 PETERSON DOES IT AGAIN! Introducing the PCT-7: Peterson Carbide Coring Tool Peterson’s new set of vending lock penetration tools make quick work of vending type lock openings including VAN lock, ABA DUO, ABLOY, BATON, 380 Tubular, 360 Tubular and 340 Tubular. The adaptor guides to a preset cutting dept insuring success every time! www.ThinkPeterson.com Standard Price: $224.95 585-264-1199 585-586-2425 (fax) Special Offer: ONLY $179.95 10am-6pm Eastern Time (Special pricing ends April 1, 2010) WE will open them — But YOU have to put them back together! TILJ_JanFeb10:TILJ 1/20/10 12:38 PM Page 3 TILJ_JanFeb10:TILJ 1/20/10 12:38 PM Page 3 NOTE FROM THE EDITOR'S DESK Greetings from the editor’s desk!!! Note From The Editor’s Desk There is a lot of news in this issue. First I would like to give a great vote of thanks for the efforts of Mike Pecorella as he substituted for Don DennisNote after Don’s From sudden health The issues. (Don Editor’s still struggles at times,Desk but I happily notice continued improvement in him). Season’s greetings from the Editor’s desk! I hope all of our readers had a safe and enjoyable Mike Season’sstepped up greetingsto the plateholiday. -

LOCKSMITH Dictionary

LOCKSMITH Dictionary Copyright , 1982 by the ALOA Sponsored National Task Group for Certified Training Programs, Master Keying Study Group Copyright , 1983 by the ALOA Sponsored National Task Group for Certified Training Programs, Master Keying Study Group Revised June, 1984 Copyright , 1996 by the Lock Industry Standards and Training Council, Master Keying Study Group Copyright , 1997 by the Lock Industry Standards and Training Council Copyright , 2000 by the Lock Industry Standards and Training Council Copyright , 2001 by the Lock Industry Standards and Training Council Copyright , 2002 by the Lock Industry Standards and Training Council Copyright , 2003 by the Lock Industry Standards and Training Council Copyright , 2004 by the Lock Industry Standards and Training Council Copyright , 2005 by the Lock Industry Standards and Training Council Copyright , 2006 by the Lock Industry Standards and Training Council Copyright , 2007 by the Lock Industry Standards and Training Council Copyright , 2009 by the Lock Industry Standards and Training Council Copyright , 2010 by the Lock Industry Standards and Training Council Copyright , 2011 by the Lock Industry Standards and Training Council Copyright , 2012 by the Lock Industry Standards and Training Council Study group and LIST Council members have included: Jerome Andrews Vaughan Armstrong Jimmy Benvenutti Greg Brandt Breck H. Camp Joe Cortie Billy B. Edwards Jr. Ken Ehrenreich G.L. Finch Dorothy Friend Kristine Gallo Ray Hern A.J. Hoffman Wiegand Jensen David J. Killip Mike Kirkpatrick William Lynk Gordon S. Morris Dan Nicholson Don O'Shall Brian O'Dowd Lloyd Seliber Jon Payne Sharon Smith John Truempy Roger Weitzenkamp Jym Welch All rights reserved. Permission is hereby granted to reprint terms and definitions contained herein with the following stipulations: 1. -

Regulatory Guide 5.12, Revision 1

U.S. NUCLEAR REGULATORY COMMISSION October 2016 OFFICE OF NUCLEAR REGULATORY RESEARCH Revision 1 Technical Lead A. Tardiff REGULATORY GUIDE REGULATORY GUIDE 5.12 (Draft was issued as DG-5027, dated January 2015) GENERAL USE OF LOCKS IN THE PROTECTION AND CONTROL OF: FACILITIES, RADIOACTIVE MATERIALS, CLASSIFIED INFORMATION, CLASSIFIED MATTER, AND SAFEGUARDS INFORMATION A. INTRODUCTION Purpose This regulatory guide (RG) describes methods and procedures that the staff of the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) considers acceptable for the selection, use, and control of locking devices. Locks can be used in the protection of: areas, facilities, certain radioactive materials, and specific types of information (e.g., classified matter, National Security Information (NSI), Restricted Data (RD), Formerly Restricted Data (FRD), Safeguards Information (SGI)). Applicable Regulations • U.S. Code of Federal Regulations, “Domestic Licensing of Production and Utilization Facilities,” Part 50, Chapter I, Title 10, “Energy” (10 CFR Part 50), (Ref. 1). Specifically Section 10 CFR 50.34 "Contents of applications" requires under (c)(1) that "[e]ach applicant for an operating license for a production or utilization facility that will be subject to §§ 73.50 and 73.60 of this chapter must include a physical security plan" and under (c)(2) "[e]ach applicant for an operating license for a utilization facility that will be subject to the requirements of § 73.55 of this chapter must include a physical security plan…" • 10 CFR Part 50, Appendix R, “Fire Protection Program for Nuclear Power Facilities Operating Prior to January 1, 1979,” requires under III.N.4, that the fire brigade leader shall have ready access to keys for any locked fire doors. -

About Locks and Ways to Low Tech Hack Them 3

CHAPTER More about locks and ways to low tech hack them 3 INFORMATION IN THIS CHAPTER • A Little More about Locks and Lock Picking • Forced Entry—And Other Ways to Cheat! • Let’s Break into a Semi–High Security Room • Keys and Key Control • Bait and Switch War Story That Could Happen to You • Some Places to Go to Learn and Have Some Fun • More about Keys and How to Make One If You Don’t Have One • Ways to Make a Key If You Didn’t Bring a Key Machine • One Final Lock to Talk about and Then We’re Done As I was preparing to write this chapter, I found myself thinking back over the past 45 years of my life. I consider myself one of the most blessed people on the planet when I think about all the things that I’ve been able to do and learn. I be- came somewhat of a techno geek while attending vocational-technical high school back in the mid-sixties. I’ve found electronics to be absolutely fascinating. In my senior year I was able to design a variable-speed (computerized) control for a synchronous motor using a handful of transistors. It was considered by the school to be their first computerized control of an AC synchronous motor. When I visited the school about 10 years later, I was pleasantly surprised to see that they were still using the training manual that I had written describing how to construct this comput- erized control. It had taken me weeks to figure out how to do this. -

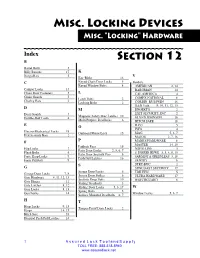

Section 12 Misc. Locking Devices

Misc. Locking Devices Misc. "Locking" Hardware Index B Section 12 Barrel Bolts 3 Billy Buttons 17 K BurglaBars 5 V Kee-Bloks 16 C Keyed Chain Door Locks 5 Vendors Keyed Window Bolts 8 AMERICAN 2, 14 Camper Locks 14 BARGMAN 14 Chain Door Fasteners 5 L CAL AMERICA 4 Chain Guards 5 Latch Bolts 2 COMPX NATIONAL 8 Charley Bars 2 Locking Bolts 2 CORBIN RUSSWIN 16 D&D Tech. 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 D M ENGERT'S 2 Door Guards 4 EXIT SECURITY, INC 2 Magnetic Safety Gate Latches 10 Double-Bolt Locks 4 GLYNN JOHNSON 16 Multi Purpose Deadlocks 6 HITCH SAFE 18 E O ILCO 5 IVES 4 Electro-Mechanical Locks 18 Outboard Motor Lock 15 MAG 5, 6, 7 Exit Security Bars 2 MAJOR 2, 7, 16 P F MARKS HARDWARE 8 MASTER 14, 15 Padlock Eyes 15 Flip Locks 7 NSP/S-LINE 3 Patio Door Locks 2, 5, 6, 7 Flush Bolts 8 S. PARKER HDWE 3, 5, 6, 8, 15 Patio Door Security Pins 6 Forte Hasp Locks 9 SARGENT & GREENLEAF 3, 18 Push Pull Latches 16 Forte PullBolt 9 SENTRY 6 S STRY-BUC 2 G SUNCOAST SECURITY 17 Screen Door Locks 6 Garage Door Locks 7, 8 TRILEEN 5 Screen Door Strikes 6 Gate Hardware 8, 11, 12, 13 ULTRA HARDWARE 17 Security Drop Bolts 10 Gate Hinges 11 WATCHGUARD 8 Sliding Deadbolts 3 Gate Latches 8, 12 Sliding Door Locks 5, 6, 17 W Gate Locks 8, 13 Spring Bolts 3 Gun Locks 14 Window Locks 5, 6, 7 Surface Mounted Deadbolts 6, 7 H T Hasp Locks 9, 15 Tamper-Proof Door Locks 2 Hasps 14, 15 Hitch Safe 18 Hospital Push/Pull Latches 16 1 A s s u r e d L o c k T o o l a n d S u p p l y TOLL FREE: 888-318-8940 www.assuredlock.net BARS, SECURITY BOLTS, LOCKING LOCKING BOLTS MAJOR Locking Bolts AFC-1976NR. -

08/12/2013 Key Issuance Procedures Purpose

Key Issuance Procedures Effective Date: 08/01/2012 Revision Date: 08/12/2013 KEY ISSUANCE PROCEDURES PURPOSE: To establish procedures governing the maintenance of access to facilities while safeguarding the personal safety and protecting the physical assets of students, faculty, and staff, protecting the property of Louisiana State University, and avoiding potentially significant costs due to theft, vandalism, or excessive rekeying of locks. The responsibility for developing and implementing key control procedures is with the Office of Facility Services. The systematic control of locks, keys and card access cards is one of the most important components of any safety program. Without proper key and card access control, locks provide little deterrence to illegal or unauthorized entry into a facility. Successful lock and key control requires the cooperation and efforts of several parties, including: Facility Services-Designs and maintains the integrity of the system LSU Police Department-Provides oversight Departments-Safeguards facilities under their use by maintaining proper key assignment policies and security systems and being financially responsible for the cost of rekeying and replacing lost keys Individual faculty, staff, and students-Safeguards assigned keys from loss or theft, and reports these occurrences immediately These procedures apply to all facilities on the Louisiana State University campus and remote locations. POLICIES 1. Keys are and remain at all times the property of Louisiana State University. 2. Keys will be issued to faculty, staff, and graduate students only. 3. Individuals are only allowed 1 issuance of a particular key, no spare keys are allowed. 4. Faculty and staff members will be issued keys consistent with job responsibilities, actual need and the approval of the Department Head or Dean. -

VA HANDBOOK 0730/4 Washington, DC 20420 Transmittal Sheet March 29, 2013

Department of Veterans Affairs VA HANDBOOK 0730/4 Washington, DC 20420 Transmittal Sheet March 29, 2013 SECURITY AND LAW ENFORCEMENT 1. REASON FOR ISSUE: This Handbook establishes mandatory procedures for protecting lives and property within VA's jurisidiction, by updating Appendix B, "Physical Security Requirements and Options." This issue provides updated requirements for securing temporary storage facilities of information technology equipment, and providing other updated physical security requirements. 2. SUMMARY OF CONTENTS AND MAJOR CHANGES: a. Summary. This replaces Appendix B of VA Handbook 0730, August 11, 2000. This Appendix sets forth specific requirements and options for protecting VA people and assets. b. Major Changes (1) Inserted physical security requirements specific to protecting VA information technology assets in temporary storage or staging areas. (2) Inserted a policy requirement for annual physical security surveys of key activities and spaces withinVA's jurisdiction. (3) Corrected errata and misnumbered paragraph items in the previous version of this Handbook. 3. RELATED DIRECTIVES: VA Directive 0730, May 27, 2010. 4. RESPONSIBLE OFFICE: The Police Service (07B), Office of Security and Law Enforcement, Office of Operations, Security, and Preparedness is responsible for the material contained in this handbook. 5. RESCISSION: Appendix B of VA Handbook 0730/2 May 27, 2010 is rescinded and replaced with this version. CERTIFIED BY: BY DIRECTION OF THE SECRETARY OF VETERANS AFFAIRS: lsI lsI Stephen W. Warren Jose D. Riojas