Beating the Bilock by Datagram & Jon King, June 2010 – January 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Medeco Product Catalog

2021 Product Catalog U.S. Prices Effective May 1, 2021 2021 Product Catalog 3 Table of Contents Medeco Mechanical Technologies Key Control ..............................................................................4 Medeco 4 High Security Locking System .........................67 How to Order ..........................................................................8 BiLevel Technology ................................................................68 Online Tools ............................................................................9 Medeco X4 Technology ........................................................69 Record of Authorization (ROA) User Guide .....................10 Shipping and Returns Policy ...............................................13 Medeco B Technology ..........................................................113 Warranty .................................................................................15 Architectural Specifications ................................................16 Mechanical Products Professional Services ............................................................19 Rim and Mortise Cylinders ..................................................71 Intelligent Key Systems Key-In-Knob/Lever Cylinders ..............................................82 Interchangeable Cores .........................................................104 Medeco XT...............................................................................23 LFIC ..........................................................................................................104 -

Cylinders & Components

Cylinders & Components Copyright © 2006, 2008-2014, Sargent Manufacturing Company, an ASSA ABLOY Group company. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part without the express written permission of Sargent Manufacturing Company is prohibited. Cylinders and Components Table of Contents KeyWizard™ Key Management Software . 1 Cylinders for Bored, Auxiliary, Integra lock and Mail Box locks . 2 Cylinder Parts: Bored, Auxiliary and Integra locks . 3 40 Series Mortise Cylinders and 34 Series Rim Cylinders . 4 Cylinder Parts: Mortise and Rim Cylinders . 5 Cams for Mortise Cylinder . 6 Installation Tools for 6300 and 7300 Cylinders . 7 6300 Large Format Interchangeable (Removable) Cores . 8 7300B Small Format Interchangeable Cores . 9 Old Style Removable Cores, Mortise/Rim Cylinders . 10 Competitive Keyway Cylinders, Bump Resistant Cylinders, Kits and Top Loading Kits . 11 124 Mortise Turn Lever Cylinders, Rosettes and Blocking Rings . 12 Construction Master Keying Lost Ball, Split Keying Construction Keying Kit (Lost Ball) . 13 Bitting Dimensions, Pins and Springs . 14 Conventional, Signature and LFIC (Removable) Core Keying Kits & Depth Key Sets . 15 Key Blanks/Key Sections, Bitting Lists . 16 Visual Key Control and Tamper Proof Packaging . 17 Master Keying and Cylinder Terms . 18 Pyramid. Cylinder & Key Control Products Absolute Keso F1 & Keso F1 with UL 437 Control High Security Cylinder Extra Signature Series & Signature Control with UL 437 High Security Keso, Restricted Keyways Intermediate XC Patented Cylinder Control Conventional -

Non -Destructive Entry Magazine

#3#3 Non-Destructive Entry Magazine Medecoder ABUS Plus Ingersoll Tiger Team And More! MayMay FOR LOCKSPORT! 20082008 WelcomeWelcome For Locksport! I received a message the other night. It was Amanda, a friend of mine who has recently taken up lockpicking. She was complaining that the challenge lock I left at her house had pricked her with a metal splinter. I told her I was sorry, she simply replied: “I HAVE BLED FOR LOCKSPORT!” I have too actually, when I first tried to make my own picks. In fact, in an informal survey I found that 100% of NDE readers who were surveyed have bled for locksport. A staggering percentage! We give our blood to these locks and it’s worth remembering what they give to us. Locks provide us not just with physical safety, but with peace of mind. They are a staple of the civilized world. A lock says “someone owns this, it’s not for you.” It’s the dividing line between the public and the private. And for the lockpicker? A lock presents a chal- lenge, a never-ending supply of new puzzles and as our hobby grows. Fueled as every- thing is now, by the internet, we see more collaboration, faster progress and ever more clever solutions to the problems the locks pose. However, there are new challenges that we should have seen coming. Specifically, how to disclose this information. The trouble is, when we get excited at our discovery and bound off to tell as many people as we can, we are celebrating what a lock means for us, it’s been conquered, the puzzle solved, the code deciphered. -

Patio Door Lock, Patio Door Pin, Patio Door Loop Lock & Patio Door Security Bar

ZZ-24 cover_Cover 2013 9/30/2013 3:10 PM Page 1 YouTube Facebook Twitter Google+ CONNECT With Prime-Line primeline.net 26950 San Bernardino Ave., Redlands, CA 92374 (909) 887-8118 • FAX - (909) 880-8968 Outside CA - (800) 255-3505 • FAX - (800) 437-7405 ZZ-24 (10-13) ©2013 Prime-Line primeline.net primeline.net ZZ-24 cover_Cover 2013 9/30/2013 3:10 PM Page 2 The NEXT generation of packaging! Vibrantly colored category designation Allows easy recognition between Window, Entry, Patio, Child and Utility Categories Larger-than-life product photographs In-use photography allows easy identification Colorful application photographs Customers see the product in practical applications for identification Reverse-sealed blister holds product and instructions Products are securely sealed in blister packs on the reverse side and include detailed installation instructions zz-24 (05-16)_ZZ-24 (09-16) 9/20/2016 10:17 AM Page 1 zz-24 (05-16)_ZZ-24 (09-16) 9/20/2016 10:17 AM Page 2 Cont ents 1 Safe Deposit Can 4 2 Re-Key A Lock Strike Plates 3 Door Knob & Wall Shields 4 Strike Plates: Adjustable, "T", Standard Latch, Security Deadbolt, Security Latch, Maximum Security Combination, Maximum Security Latch, Maximum Security Deadbolt, & Armored Security 10 Lock & Door Reinforcers: Recessed & Non-Recessed Edge, Door Edge & Frame Reinforcer, Decorative Door Reinforcer, Blank Reinforcer & Mega Jamb 10 15 Latch Shields: Lock & Door Reinforcers Protector, Shields, Bore Reducer, Door Edge Filler Plate, Cover Plate & Hole Cover 19 Window & Door Security: Sliding Window -

Auxiliary Locks Cabinet Locks, Deadlocks, Padlocks Table of Contents

Auxiliary Locks Cabinet Locks, Deadlocks, Padlocks Table of Contents Contents Yale Commercial Solutions .................................................... 3 Finishes ..................................................................................... 4 How to Order ............................................................................ 5 D Series Cylindrical Deadbolts ......................................... 6-11 Mortise Deadlocks ...........................................................12-13 Padlocks ............................................................................14-18 Auxiliary Rim Locks/Components ................................. 19-25 Cabinet Locks ........................................................................ 26 Special Purpose Locks ......................................................... 27 Electrical Switch Cylinders ................................................... 28 YSSL10 Auxiliary Latch ......................................................... 29 Copyright © 2002-2021, ASSA ABLOY Access and Egress Hardware Group, Inc. All rights reserved. 2 Reproduction in whole or in part without the express written permission of ASSA ABLOY Access and Egress Auxiliary Locks Hardware Group, Inc. is prohibited. Patent pending and/or patent www.assaabloydss.com/patents. Auxiliary Locks Yale provides a wide range of auxiliary and special purpose locks designed to fit a variety of demanding applications. Product offerings include high quality latchlocks, deadlocks, deadbolts and rim locks with both standard -

Keying Systems and Nomenclature

KEYING SYSTEMS AND NOMENCLATURE Keying Procedures, Systems, and and the authors of the previous FOREWORD Nomenclature was first published in editions should take pride in the 1965, revised in 1969, 1975 and again results. in 1978. It introduced a procedural There are still some misapplications system of keying terminology radically and misunderstandings of the system different from that commonly used and it is the purpose of this edition to prior to 1965. The need for standard clarify the system to avoid terminology was clear but the misunderstanding. With this in mind, acceptance of the new system was text and format changes have been slow. made with the aim of introducing Manufacturers, Distributors, Building criteria in their order of complexity, to Owners, and Operators were make the manual an even better frustrated over the use of various and instructional tool for those progressing differing terms. Among those using the through basic, intermediate, and terms, different meanings and advanced study of the subject. interpretations were applied. As a Since the manual does not cover result, errors were made, and frequent actual keying procedures, the title of correspondence occurred between the manual has been changed. For manufacturers and distributors, those interested in the actual seeking clarification. The consumer techniques of keying or the sometimes had a sketchy mathematics of setting up a key understanding of the key system he system, many fine books and had purchased. publications are offered by the lock- Since its inception, the procedures smithing industry. outlined in this manual have been taught at the DHI Technical Programs Robert Perry, AHC/CDC John R. -

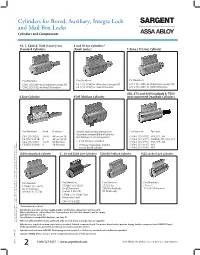

Cylinders for Bored, Auxiliary, Integra Lock and Mail Box Locks Cylinders and Components

Cylinders for Bored, Auxiliary, Integra Lock and Mail Box Locks Cylinders and Components 10, 7, 6500 & 7500 (Lever) Line 8 and 9 Line Cylinders* Standard Cylinders (Knob Locks) T-Zone (11 Line) Cylinder Part Numbers: Part Numbers: Part Numbers: C10-1 (13-3266) for all functions (except 50) C8-1 (13-2194) for all functions (except 50) C11-1 (13-4145) for all functions (except 50) C10-2 (13-3492) for Hotel 50 function C8-2 (13-2195) for Hotel 50 function C11-2 (13-4146) for Hotel 50 function 460, 470 and 480 Deadbolt & 7500 6 Line Cylinder 4101 Mailbox Cylinder Interconnected Deadbolt Cylinders Part Numbers: Knob Function Consult mailbox manufacturer to Part Numbers: Function determine compatibility of cylinder C6-1 (13-3129) S & N All except 50 and mailbox . 5 or 6 pin systems C480-1 (13-3456) 454, 474, 484 C6-1B (13-3130) B All except 50 C480-2 (13-3457) 7500DB, 455, 485, 487 C6-2 (13-3108) S & N 50 Function • 2 cut day keys provided C480-3 (13-3458) 456, 475, 486 C6-2B (13-3109) B 50 Function • US Postal regulations prohibit C460-1 (13-3495) 464 master keyed cylinder C460-2 (13-3496) 465 7600 Integralock Cylinder 5*, 8X and 5500 Line Cylinders 758/858 Padlock Cylinder 1655 Locker Lock Cylinder Part Number: Part Numbers: Part Numbers: Part Numbers: C7600-1 (13-3987) C5500-1 (13-3526) C750-1 for C1655-1 for all functions for all functions 758/858 Padlocks 13-1813 (tail piece) (except 26, 27, 50) (except 5 line 50) 04 Finish only C5500-2 (13-3708) 5 line 50 function hotel C8X-1 (13-5202) * Discontinued products All cylinders are 6 pin and are supplied with 2 nickel silver change keys unless noted. -

Section D - Cabinet Locks & Latches

Section D - Cabinet Locks & Latches SECTION D - TABLE OF CONTENTS A Section D Contents: B Olympus Locks → National Lock Overview............................. 2 D-32 - D-41 C Removacore Locks....................................... 3 Disc Tumbler Cam & D Deadbolt Locks...................................... 4 - 7 Pin Tumbler Cam & EE Deadbolt Locks.......................................8 - 9 Timberline → Interchangeable FF National Lock Accessories................10 - 11 Lock Plug System SlamCAM/SlamStrike...............................12 pages D-16 - D-31 G Keyless Locks......................................13 - 15 Timberline Lock Overview.........................16 H Timberline Lock Cylinder Bodies.......17 - 29 Timberline Lock Plugs I & Accessories.................................... 30 - 31 Olympus Lock overview............................32 J Olympus Padlockable Camlock 33 Double Door KK Olympus Cam/Deadbolt Locks........34 - 35 Latches → Olympus Cam/ page D-45 L Deadbolt Lock Bodies.......................36 - 37 Olympus SFIC Cylinders.......................... 38 MM CompX National Olympus Lock Accessories............... 39 - 41 ← Disc & Pin Tumbler Cam Specialty & Showcase Locks............ 42 - 45 Locks NN Strikes & Catches.............................. 46 - 56 pages D-4 - D-12 OO PP ↓Keyless Locks pages D-13 - D-15 QQ R Magnetic Catches → S pages D-46 - T D-47 U ← Elbow Catches V page D-55 WW XX Y Roller Catches page D-53↑ 800-289-2237 • WWW.WURTHBAERSUPPLY.COM • WÜRTH BAER SUPPLY D - 1 Section D - Cabinet Locks & Latches A NATIONAL LOCK OVERVIEW B A Lock Is A Lock…..Or Is It? C Disc Tumbler, Pin Tumbler & Deadbolt Locks: D Disc Tumbler Cam Locks sometimes referred to as “wafer locks” are inexpensive, low security locks with limited keying capabilities. Master keying for disc tumbler locks is limited to only one level. The disc tumbler lock consists of chambers with only one disc per chamber which raises or lowers as the key E passes through the window that is cut into the disc. -

Keys a Key Is an Instrument That Is Used to Operate a Lock

CSCLA PRESS September 19th Time 7:00pm At the Church CSCLA CSCLA President Secretary Mike Middick, CML Pete Henley Middick’s Locksmith Shop Henley's Key Service 1422 Royal Gorge Blvd. 117 E Boulder St. Canon City CO 81212-3908 Colorado Springs CO 80903 Ph. 719-275-7787 Fax 719-275-3278 719 338-0889 Email - captkeyman@ gmail.com Email - [email protected] Vice-President Members at Large Paul Arens 141 E Navajo Carl Price Colorado Springs CO 80906-2255 Ron Cox 719-632-5085 Steve Cormier Email - [email protected] Treasurer Newsletter Editor Barry Meyer, CPL Acoma Locksmith Service Could be you. 421 Perry St. Now awaiting for you to volunteer! Castle Rock CO 80104-2442 303-688-4104 Send info to the president. Email - [email protected] CSCLA STATEMENT OF MISSION & PURPOSE The mission and purpose is to encourage, promote, aid in and affect the voluntary interchange, among members of the CSCLA, of data, information, experience, ideas, knowledge, methods and techniques relating to the field of Locksmithing. Central & Southern Colorado Locksmith Association Founded 1991 DISCLAIMER The CSCLA Press is the publication of the Central & Southern Colorado Locksmiths Association. Other locksmith organizations may use or copy the CSCLA Press (except text taken from copyrighted publications) without written consent, provided it is used to better the industry and proper credit is given. We reserve the right to edit articles for clarity and space, and contributions remain the property of CSCLA. Any articles or opinions expressed in this publication unless identified by the author’s name or contributing organization are solely those of the editor. -

2340-002-ASSA ABLOY Key Control Design Guide

Key Control Design Guide Increase the Safety and Security of Your Facility A security solution from ASSA ABLOY Group brands: CORBIN RUSSWIN | MEDECO | SARGENT | YALE Contents I. Introduction . 2 II. Recommended Companion Document . 3 III. Comprehensive Model Key Control Policy a. Purpose. 4 b. Specification. 5 c. Enforcement . 6 d. Elements of a Key Control Policy . 7 Key Control Authority (KCA). 7 Storage. 7 Key Management Formats . 8 Record Keeping . 10 Policies and Procedures . 10 1. Identifying Keys and Keying 2. Issuing Keys 3. Returning Keys 4. Non-returned key policy 5. Administration of the Master Key System 6. Audits 7. Transfer/Temporary use Forms. 13 Servicing . 15 IV. Condensed Model Key Control Policy . 16 V. Specific Applications: a. Educational K-12. 18 b. Healthcare Facilities . 19 c. Colleges and Universities . 21 d. Office Buildings. 22 VI. Glossary of Terms and Definitions. 23 © ASSA ABLOY SALES & MARKETING GROUP INC. 2005, 2006, 2007. All rights reserved. 3 Introduction This “Key Control Design Guide” is brought to you by ASSA ABLOY, the world’s leading group of manufacturers and suppliers of locking solutions, dedicated to satisfying end-users’ needs for security and safety. Providing key systems and associated hardware is only the beginning. For end-users to successfully enjoy the benefits of the products we furnish, and to extend the life and value of a key system, proper policies must be in place. The policies and procedures suggested in this manual can play an essential part in increasing the safety and security of any facility. This manual should be used as a model or guide only. -

September/October 2010 Issu E 24 – $14.00 TILJ Janfeb10:TILJ 1/20/10 12:38 PM Page 2

The I nde pe nd en t September/October 2010 L Issue 24 – $14.00 o c k s m i t h h h J J J o o o u u u r r r n n n a a a l l l TILJ_JanFeb10:TILJ 1/20/10 12:38 PM Page 2 PETERSON DOES IT AGAIN! Introducing the PCT-7: Peterson Carbide Coring Tool Peterson’s new set of vending lock penetration tools make quick work of vending type lock openings including VAN lock, ABA DUO, ABLOY, BATON, 380 Tubular, 360 Tubular and 340 Tubular. The adaptor guides to a preset cutting dept insuring success every time! www.ThinkPeterson.com Standard Price: $224.95 585-264-1199 585-586-2425 (fax) Special Offer: ONLY $179.95 10am-6pm Eastern Time (Special pricing ends April 1, 2010) WE will open them — But YOU have to put them back together! TILJ_JanFeb10:TILJ 1/20/10 12:38 PM Page 3 TILJ_JanFeb10:TILJ 1/20/10 12:38 PM Page 3 NOTE FROM THE EDITOR'S DESK Greetings from the editor’s desk!!! Note From The Editor’s Desk There is a lot of news in this issue. First I would like to give a great vote of thanks for the efforts of Mike Pecorella as he substituted for Don DennisNote after Don’s From sudden health The issues. (Don Editor’s still struggles at times,Desk but I happily notice continued improvement in him). Season’s greetings from the Editor’s desk! I hope all of our readers had a safe and enjoyable Mike Season’sstepped up greetingsto the plateholiday. -

Disc Tumbler Locks

8994 Layout 12/9/99 9:36 AM Page 1 Cabinet Locks Manufactured to Order MADEMADE ININ U.S.A.U.S.A. A2695 ISO 9001 8994 Layout 12/9/99 9:41 AM Page 2 Designing Locks for Your Needs At National Cabinet Lock, every effort is As an ISO 9001 registered company, Quality directed towards proficiency in engineering, Assurance and SPC programs monitor all designing and production, so we earn cus- phases of production. National Cabinet tomer confidence in the high quality and Lock customers can be confident they are dependable perfomance of our products. purchasing locks they will be proud to use Through innovative product development by to provide security on their own manufac- use of analysis tools such as 3D modeling tured products. and rapid prototyping, National Cabinet Lock continually focuses on collaborating As one of the few remaining cabinet lock with customer engineering departments to manufacturers, who value what “Made in develop products to meet their special USA” has to offer, we have invested in needs. With standard products and cus- automated production facilities in South tomized versions of its core product line, Carolina to manufacture our products. We National Cabinet Lock has met and exceed- are committed to maintaining dependable ed changing customer requirements since service to our customers as we have for 1903. nearly one hundred years since our found- ing. Our use of Finite Element Modeling and Failure Mode and Effects Analysis provides essential and useful insight into the strength and design attributes of the locks that we develop. Mixed-model scheduling procedures and the use of kanban produc- tion principles help provide products quick- er and at lower costs.