Need for Supply Augmentation and Demand Management to Mitigate Impacts of Climate Change on the Water Sector

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abstract No: 11 Earth and Environmental Sciences

Proceedings of the Postgraduate Institute of Science Research Congress, Sri Lanka: 26th - 28th November 2020 Abstract No: 11 Earth and Environmental Sciences PRIORITIZATION OF WATERSHEDS IN UVA PROVINCE, SRI LANKA, BASED ON SOIL EROSION HAZARD I.D.U.H. Piyathilake1*, R.G.I. Sumudumali1, E.P.N. Udayakumara2, L.V. Ranaweera2, J.M.C.K. Jayawardana2 and S.K. Gunatilake2 1Faculty of Graduate Studies, Sabaragamuwa University of Sri Lanka, Belihuloya, Sri Lanka 2Department of Natural Resources, Sabaragamuwa University of Sri Lanka, Belihuloya, Sri Lanka *[email protected] Uva Province in Sri Lanka is most significant in terms of its hydrological contributions since it consists of ten major river basins including source areas of three tributaries of Mahaweli River. The Province is affected by human-induced soil erosion by water. Hence, identification of soil erosion hazards and prioritizing them based on watersheds are crucial for improving soil conservation and water management plans. This study assessed the mean annual soil loss from the Province and watersheds separately using the Integrated Valuation of Ecosystem Services and Tradeoffs (InVEST) Sediment Delivery Ratio (SDR) model introduced by the Stanford University, USA, using ArcGIS 10.4 environment. To cover the spatial extent of the Uva Province, the raster maps of Digital Elevation Model (DEM), rainfall erosivity factor (R), soil erodibility factor (K), and land use land cover (LULC) maps were prepared using ArcGIS 10.4. A biophysical table was formulated as a .csv (Comma Separated Value) table containing crop management (C) and support practice (P) factors corresponding to each land use classes in the LULC raster. -

Fit.* IRRIGATION and MULTI-PURPOSE DEVELOPMENT

fit.* The Historic Jaya Ganga — built by King Dbatustna in tbi <>tb century AD to carry the waters of the Kala Wewa to the ancient city tanks of Anuradbapura, 57 miles away, while feeding a number of village tanks in its course. This channel is also famous for the gentle gradient of 6 ins. per mile for the first I7 miles and an average of 1 //. per mile throughout its length. Both tbeKalawewa andtbefiya Garga were restored in 1885 — 18 8 8 by the British, but not to their fullest capacities. New under the Mabaweli Diversion project, the Kill Wewa his been augmented and the Jaya Gingi improved to carry 1000 cusecs of water. The history of our country dates back to the 6th century B.C. When the legendary Vijaya landed in L->nka, he is believed to have found an island occupied by certain tribes who had already developed a rudimentary sys tem of irrigation. Tradition has it that Kuveni was spinning cotton on the bund of a small lake which was presumably part of this ancient system. The development of an ancient civilization which was entirely depen dent on an irrigation system that grew in size and complexity through the years is described in our written history. Many examples are available which demonstrate this systematic development of water and land re sources throughout the so-called dry zone of our country over very long periods of time. The development of a water supply and irrigation system around the city of Anuradhapuia may be taken as an example. -

An Assessment of the Water Quality in Major Streams of the Madu Ganga Catchment and Pollution Loads Draining Into the Madu Ganga from Its Own Catchment

An assessment of the water quality in major streams of the Madu Ganga catchment and pollution loads draining into the Madu Ganga from its own catchment A.A.D. Amarathunga* and N. Sureshkumar National Aquatic Resources Research and Development Agency (NARA), Crow Island, Colombo 15, Sri Lanka. Abstract The Madu Ganga Lagoon is located in the Southern Coast, Northwest of the city of Galle within the Galle District. The aim of this study was to evaluate the pollution status of the lagoon and the contribution of the land base pollutants from the catchment of the Madu Ganga. Selected water quality parameters were measured at monthly intervals at twelve sampling locations in the catchment. Certain parameters such as salinity (2.2 + 1.7 ppt), oil & grease (8.5 + 6.5 mg/L), total suspended solids (16.1 ± 12.3 mg/L), and turbidity (20.1 ± 12.5 NTU) are found to be elevated levels when compared with water quality standards. The study revealed that the Lenagala Ela brought a high nutrient load (426.7 kg/day) into Madu Ganga and Arawavilla Ela, Magala Ela and Bogaha Ela also contributed significantly. The highest nutrient loads were found with the onset of the Northeast Monsoon during November to January. The increase in nutrient loads is attributed to the fertilizers added to the soil with the commencement of the major paddy cultivation season. Keywords: Physico-chemical parameters, Madu Ganga, Water pollution, Nutrient load, Suspended sediment ^Corresponding author - Email: deeptha(s>nara.ac.lk, [email protected] Journal of the National Aquatic Resources Research and Development Agency, Vol. -

The Government of the Democratic

THE GOVERNMENT OF THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA FINANCIAL STATEMENTS OF THE GOVERNMENT FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31ST DECEMBER 2019 DEPARTMENT OF STATE ACCOUNTS GENERAL TREASURY COLOMBO-01 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. 1. Note to Readers 1 2. Statement of Responsibility 2 3. Statement of Financial Performance for the Year ended 31st December 2019 3 4. Statement of Financial Position as at 31st December 2019 4 5. Statement of Cash Flow for the Year ended 31st December 2019 5 6. Statement of Changes in Net Assets / Equity for the Year ended 31st December 2019 6 7. Current Year Actual vs Budget 7 8. Significant Accounting Policies 8-12 9. Time of Recording and Measurement for Presenting the Financial Statements of Republic 13-14 Notes 10. Note 1-10 - Notes to the Financial Statements 15-19 11. Note 11 - Foreign Borrowings 20-26 12. Note 12 - Foreign Grants 27-28 13. Note 13 - Domestic Non-Bank Borrowings 29 14. Note 14 - Domestic Debt Repayment 29 15. Note 15 - Recoveries from On-Lending 29 16. Note 16 - Statement of Non-Financial Assets 30-37 17. Note 17 - Advances to Public Officers 38 18. Note 18 - Advances to Government Departments 38 19. Note 19 - Membership Fees Paid 38 20. Note 20 - On-Lending 39-40 21. Note 21 (Note 21.1-21.5) - Capital Contribution/Shareholding in the Commercial Public Corporations/State Owned Companies/Plantation Companies/ Development Bank (8568/8548) 41-46 22. Note 22 - Rent and Work Advance Account 47-51 23. Note 23 - Consolidated Fund 52 24. Note 24 - Foreign Loan Revolving Funds 52 25. -

Water Balance Variability Across Sri Lanka for Assessing Agricultural and Environmental Water Use W.G.M

Agricultural Water Management 58 (2003) 171±192 Water balance variability across Sri Lanka for assessing agricultural and environmental water use W.G.M. Bastiaanssena,*, L. Chandrapalab aInternational Water Management Institute (IWMI), P.O. Box 2075, Colombo, Sri Lanka bDepartment of Meteorology, 383 Bauddaloka Mawatha, Colombo 7, Sri Lanka Abstract This paper describes a new procedure for hydrological data collection and assessment of agricultural and environmental water use using public domain satellite data. The variability of the annual water balance for Sri Lanka is estimated using observed rainfall and remotely sensed actual evaporation rates at a 1 km grid resolution. The Surface Energy Balance Algorithm for Land (SEBAL) has been used to assess the actual evaporation and storage changes in the root zone on a 10- day basis. The water balance was closed with a runoff component and a remainder term. Evaporation and runoff estimates were veri®ed against ground measurements using scintillometry and gauge readings respectively. The annual water balance for each of the 103 river basins of Sri Lanka is presented. The remainder term appeared to be less than 10% of the rainfall, which implies that the water balance is suf®ciently understood for policy and decision making. Access to water balance data is necessary as input into water accounting procedures, which simply describe the water status in hydrological systems (e.g. nation wide, river basin, irrigation scheme). The results show that the irrigation sector uses not more than 7% of the net water in¯ow. The total agricultural water use and the environmental systems usage is 15 and 51%, respectively of the net water in¯ow. -

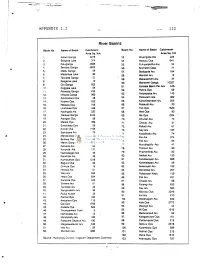

River Basins

APPENDIX I.I 122 River Basins Basin No Name of Basin Catchment Basin No. Name of Basin Catchment Area Sq. Km. Area Sq. Km 1. Kelani Ganga 2278 53. Miyangolla Ela 225 2. Bolgoda Lake 374 54. Maduru Oya 1541 3. Kaluganga 2688 55. Pulliyanpotha Aru 52 4. Bemota Ganga 6622 56. Kirimechi Odai 77 5. Madu Ganga 59 57. Bodigoda Aru 164 6. Madampe Lake 90 58. Mandan Aru 13 7. Telwatte Ganga 51 59. Makarachchi Aru 37 8. Ratgama Lake 10 60. Mahaweli Ganga 10327 9. Gin Ganga 922 61. Kantalai Basin Per Ara 445- 10. Koggala Lake 64 62. Panna Oya 69 11. Polwatta Ganga 233 12. Nilwala Ganga 960 63. Palampotta Aru 143 13. Sinimodara Oya 38 64. Pankulam Ara 382 14. Kirama Oya 223 65. Kanchikamban Aru 205 15. Rekawa Oya 755 66. Palakutti A/u 20 16. Uruhokke Oya 348 67. Yan Oya 1520 17. Kachigala Ara 220 68. Mee Oya 90 18. Walawe Ganga 2442 69. Ma Oya 1024 19. Karagan Oya 58 70. Churian A/u 74 20. Malala Oya 399 71. Chavar Aru 31 21. Embilikala Oya 59 72. Palladi Aru 61 22. Kirindi Oya 1165 73. Nay Ara 187 23. Bambawe Ara 79 74. Kodalikallu Aru 74 24. Mahasilawa Oya 13 75. Per Ara 374 25. Butawa Oya 38 76. Pali Aru 84 26. Menik Ganga 1272 27. Katupila Aru 86 77. Muruthapilly Aru 41 28. Kuranda Ara 131 78. Thoravi! Aru 90 29. Namadagas Ara 46 79. Piramenthal Aru 82 30. Karambe Ara 46 80. Nethali Aru 120 31. -

List of Rivers of Sri Lanka

Sl. No Name Length Source Drainage Location of mouth (Mahaweli River 335 km (208 mi) Kotmale Trincomalee 08°27′34″N 81°13′46″E / 8.45944°N 81.22944°E / 8.45944; 81.22944 (Mahaweli River 1 (Malvathu River 164 km (102 mi) Dambulla Vankalai 08°48′08″N 79°55′40″E / 8.80222°N 79.92778°E / 8.80222; 79.92778 (Malvathu River 2 (Kala Oya 148 km (92 mi) Dambulla Wilpattu 08°17′41″N 79°50′23″E / 8.29472°N 79.83972°E / 8.29472; 79.83972 (Kala Oya 3 (Kelani River 145 km (90 mi) Horton Plains Colombo 06°58′44″N 79°52′12″E / 6.97889°N 79.87000°E / 6.97889; 79.87000 (Kelani River 4 (Yan Oya 142 km (88 mi) Ritigala Pulmoddai 08°55′04″N 81°00′58″E / 8.91778°N 81.01611°E / 8.91778; 81.01611 (Yan Oya 5 (Deduru Oya 142 km (88 mi) Kurunegala Chilaw 07°36′50″N 79°48′12″E / 7.61389°N 79.80333°E / 7.61389; 79.80333 (Deduru Oya 6 (Walawe River 138 km (86 mi) Balangoda Ambalantota 06°06′19″N 81°00′57″E / 6.10528°N 81.01583°E / 6.10528; 81.01583 (Walawe River 7 (Maduru Oya 135 km (84 mi) Maduru Oya Kalkudah 07°56′24″N 81°33′05″E / 7.94000°N 81.55139°E / 7.94000; 81.55139 (Maduru Oya 8 (Maha Oya 134 km (83 mi) Hakurugammana Negombo 07°16′21″N 79°50′34″E / 7.27250°N 79.84278°E / 7.27250; 79.84278 (Maha Oya 9 (Kalu Ganga 129 km (80 mi) Adam's Peak Kalutara 06°34′10″N 79°57′44″E / 6.56944°N 79.96222°E / 6.56944; 79.96222 (Kalu Ganga 10 (Kirindi Oya 117 km (73 mi) Bandarawela Bundala 06°11′39″N 81°17′34″E / 6.19417°N 81.29278°E / 6.19417; 81.29278 (Kirindi Oya 11 (Kumbukkan Oya 116 km (72 mi) Dombagahawela Arugam Bay 06°48′36″N -

Securing the Food Supply and Food Security of the Ruhuna Basin

Securing the Food Supply and Food Security of the Ruhuna Basin K. D. N. Weerasinghe\ Ananda Jayasinghe2 and A. M. H. Abeysinghe3 1. Geographical Informations of the Ruhuha Basins Ruhuna basin situates in southern Sri Lanka totaling 5578 sq krn. It has four major river basins viz: Walawe Ganga, Kirindi Oya, Malala Oya and Menik Ganga. There are 3 Agro-ecological zones in the Ruhuna Basin namely Wet, Wet Intermediate and Dry Intermediate zones. Major River Basins of the Ruhuna basin and their catchments are given in the table 1 and figure 1. Table 1. Major river basins and catchments. Name Catchment's area (Km2) 1. Walawe Ganga 2471 2. Kiridi Oya 1165 3. Menik Ganga 1287 4. Malala Oya 402 5. Other 235 Total 5578 Palitha et aI, 1999) Total area of the Ruhuna Basin is c0vered by catchments of Walawe Ganga, Kirindi Oya, Malala Oya, Manik Ganga and number of small catchments. Detailed map of the river basins in the Hambantota District as documented by J. L. Sabatier (2001), is given in the figure 1. There are 19 river basins in the district and out of which 10 river basins are included in to the Ruhuna basin, except, Seenimodera, Kirama, Rekawa,Urubokke Oya, in the west and Katupila Ara, Kurundu Ara, Nemadegan Ara, Karambe Ara, and Kumbukkan Oya in the east (Figure 1). Further more as pointed out by Arumugam (1969), most of these basins are small and they do not make any effective contribution to the water resources. Malala Oya basin has a catchment of 404 sq. -

Y%S ,Xld M%Cd;Dka;%Sl Iudcjd§ Ckrcfha .Eiü M;%H W;S Úfyi the Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka EXTRAORDINARY

Y%S ,xld m%cd;dka;%sl iudcjd§ ckrcfha .eiÜ m;%h w;s úfYI The Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka EXTRAORDINARY wxl 2072$58 - 2018 uehs ui 25 jeks isl=rdod - 2018'05'25 No. 2072/58 - FRIDAY, MAY 25, 2018 (Published by Authority) PART I : SECTION (I) — GENERAL Government Notifications SRI LANKA Coastal ZONE AND Coastal RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PLAN - 2018 Prepared under Section 12(1) of the Coast Conservation and Coastal Resource Management Act, No. 57 of 1981 THE Public are hereby informed that the Sri Lanka Coastal Zone and Coastal Resource Management Plan - 2018 was approved by the cabinet of Ministers on 25th April 2018 and the Plan is implemented with effect from the date of Gazette Notification. MAITHRIPALA SIRISENA, Minister of Mahaweli Development and Environment. Ministry of Mahaweli Development and Environment, No. 500, T. B. Jayah Mawatha, Colombo 10, 23rd May, 2018. 1A PG 04054 - 507 (05/2018) This Gazette Extraordinary can be downloaded from www.documents.gov.lk 1A 2A I fldgi ( ^I& fPoh - YS% ,xld m%cd;dka;s%l iudcjd§ ckrcfha w;s úfYI .eiÜ m;%h - 2018'05'25 PART I : SEC. (I) - GAZETTE EXTRAORDINARY OF THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA - 25.05.2018 CHAPTER 1 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 THE SCOPE FOR COASTAL ZONE AND COASTAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT 1.1.1. Context and Setting With the increase of population and accelerated economic activities in the coastal region, the requirement of integrated management focused on conserving, developing and sustainable utilization of Sri Lanka’s dynamic and resources rich coastal region has long been recognized. -

12 Manogaran.Pdf

Ethnic Conflict and Reconciliation in Sri Lanka National Capilal District Boundarl3S * Province Boundaries Q 10 20 30 010;1)304050 Sri Lanka • Ethnic Conflict and Reconciliation in Sri Lanka CHELVADURAIMANOGARAN MW~1 UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII PRESS • HONOLULU - © 1987 University ofHawaii Press All Rights Reserved Manufactured in the United States ofAmerica Library ofCongress Cataloging-in-Publication-Data Manogaran, Chelvadurai, 1935- Ethnic conflict and reconciliation in Sri Lanka. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Sri Lanka-Politics and government. 2. Sri Lanka -Ethnic relations. 3. Tamils-Sri Lanka-Politics and government. I. Title. DS489.8.M36 1987 954.9'303 87-16247 ISBN 0-8248-1116-X • The prosperity ofa nation does not descend from the sky. Nor does it emerge from its own accord from the earth. It depends upon the conduct ofthe people that constitute the nation. We must recognize that the country does not mean just the lifeless soil around us. The country consists ofa conglomeration ofpeople and it is what they make ofit. To rectify the world and put it on proper path, we have to first rec tify ourselves and our conduct.... At the present time, when we see all over the country confusion, fear and anxiety, each one in every home must con ., tribute his share ofcool, calm love to suppress the anger and fury. No governmental authority can sup press it as effectively and as quickly as you can by love and brotherliness. SATHYA SAl BABA - • Contents List ofTables IX List ofFigures Xl Preface X111 Introduction 1 CHAPTER I Sinhalese-Tamil -

Statistical Book

Mahaweli Authority of Sri Lanka Socio – Economic Statistics 2018 Mahaweli Authority of Sri Lanka Mahaweli Authority of Sri Lanka was Established Under Act No. 23 of 1979 VISION “The best organization in Sri Lanka, in excellence use of land & water for the innovative Agriculture, renewable energy, conserving environment and raising the living standards of citizens” MISSION “We strive to lead the use of land & water for the innovative Agriculture productivity based on the latest technology supplementing the generation of renewable energy, best environment and tourism for the enrichment of the Sri Lankan community and their living standards” Contents Selected Economic and Social Indicators I- IV 1. Introduction 01-02 2. Background Information 03-05 2.1. Mahaweli Areas belonging to the Mahaweli Authority of Sri Lanka 2.2. Basic Information on Mahaweli Areas 3. Irrigation and Power Generation 06-16 3.1. Current Water Capacity of Irrigation Reservoirs for Agriculture as at 31.12.2018 3.2. Hydropower Generation in Major Reservoirs and Mini Hydropower Stations 4. Land Development 17-20 5. Settlement and Household Information 21-29 6. Economic and Social Infrastructure Facilities 30-37 6.1. Social Infrastructure Facilities (Cumulative) 6.2. Social and Economic Infrastructure Facilities (Cumulative) – 2018 6.3. Distribution of Type of Schools in Mahaweli Areas – 2018 6.4. Economic Infrastructure Facilities (Cumulative) 7. Agriculture and Livestock 38-84 7.1. Agriculture 7.2. Extent and Production of Other Field Crops in Mahaweli Areas 7.3. Livestock and Inland Fish 8. Investment Projects in Mahaweli Areas 85-86 9. SME Loan Facilities in Mahaweli Areas – 2018 87-88 10. -

Eastern Province

Resettlement Due Diligence Report June 2017 SRI: Second Integrated Road Investment Program Eastern Province Prepared by Road Development Authority, Ministry of Higher Education and Highways for the Government of Sri Lanka and the Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 30 May 2017) Currency unit – Sri Lanka Rupee (SLRl} SLR1.00 = $ 0.00655 $1.00 = Rs 152.63 ABBREVIATIONS ADB - Asian Development Bank DSD - Divisional Secretariat Division DS - Divisional Secretariat EP - Eastern Province EPL - Environmental Protection License DDR - Due Diligence Report FGD - Focus Group Discussion GDP - Gross Domestic Production GoSL - Government of Sri Lanka GN - Grama Niladari GND - Grama Niladari Division GRC - Grievance Redress Committee GSMB - Geological Survey and Mines Bureau HH - Household iRoad - Integrated Road Investment Program iRoad 2 - Second Integrated Road Investment Program IR - Involuntary Resettlement MoHEH - Ministry of Higher Education and Highways NWS&DB - National Water Supply and Drainage Board OFC - Other Field Crops PS - Pradeshiya Sabha PPE - Personal Protective Equipment’s RDA - Road Development Authority RF - Resettlement Framework ROW - Right of Way SAPE - Survey and Preliminary Engineering SLR - Sri Lankan Rupees This resettlement due diligence report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area.