The Chaco Experience Landscape and Ideology at the Center Place

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Primary Architecture of the Chacoan Culture

9 The Primary Architecture of the Chacoan Culture A Cosmological Expression Anna Sofaer TUDIES BY THE SOLSTICE PROJECT indicate that the solar-and-lunar regional pattern that is symmetri- Smajor buildings of the ancient Chacoan culture cally ordered about Chaco Canyon’s central com- of New Mexico contain solar and lunar cosmology plex of large ceremonial buildings (Sofaer, Sinclair, in three separate articulations: their orientations, and Williams 1987). These findings suggest a cos- internal geometry, and geographic interrelation- mological purpose motivating and directing the ships were developed in relationship to the cycles construction and the orientation, internal geome- of the sun and moon. try, and interrelationships of the primary Chacoan From approximately 900 to 1130, the Chacoan architecture. society, a prehistoric Pueblo culture, constructed This essay presents a synthesis of the results of numerous multistoried buildings and extensive several studies by the Solstice Project between 1984 roads throughout the eighty thousand square kilo- and 1997 and hypotheses about the conceptual meters of the arid San Juan Basin of northwestern and symbolic meaning of the Chacoan astronomi- New Mexico (Cordell 1984; Lekson et al. 1988; cal achievements. For certain details of Solstice Pro- Marshall et al. 1979; Vivian 1990) (Figure 9.1). ject studies, the reader is referred to several earlier Evidence suggests that expressions of the Chacoan published papers.1 culture extended over a region two to four times the size of the San Juan Basin (Fowler and Stein Background 1992; Lekson et al. 1988). Chaco Canyon, where most of the largest buildings were constructed, was The Chacoan buildings were of a huge scale and the center of the culture (Figures 9.2 and 9.3). -

Ancient Maize from Chacoan Great Houses: Where Was It Grown?

Ancient maize from Chacoan great houses: Where was it grown? Larry Benson*†, Linda Cordell‡, Kirk Vincent*, Howard Taylor*, John Stein§, G. Lang Farmer¶, and Kiyoto Futaʈ *U.S. Geological Survey, Boulder, CO 80303; ‡University Museum and ¶Department of Geological Sciences, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309; §Navajo Nation Historic Preservation Department, Chaco Protection Sites Program, P.O. Box 2469, Window Rock, AZ 86515; and ʈU.S. Geological Survey, MS 963, Denver Federal Center, Denver, CO 80225 Edited by Jeremy A. Sabloff, University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia, PA, and approved August 26, 2003 (received for review August 8, 2003) In this article, we compare chemical (87Sr͞86Sr and elemental) analyses of archaeological maize from dated contexts within Pueblo Bonito, Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, to potential agricul- tural sites on the periphery of the San Juan Basin. The oldest maize analyzed from Pueblo Bonito probably was grown in an area located 80 km to the west at the base of the Chuska Mountains. The youngest maize came from the San Juan or Animas river flood- plains 90 km to the north. This article demonstrates that maize, a dietary staple of southwestern Native Americans, was transported over considerable distances in pre-Columbian times, a finding fundamental to understanding the organization of pre-Columbian southwestern societies. In addition, this article provides support for the hypothesis that major construction events in Chaco Canyon were made possible because maize was brought in to support extra-local labor forces. etween the 9th and 12th centuries anno Domini (A.D.), BChaco Canyon, located near the middle of the high-desert San Juan Basin of north-central New Mexico (Fig. -

A Navajo Myth from the Chaco Canyon Gretchen Chapin

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of New Mexico New Mexico Anthropologist Volume 4 | Issue 4 Article 4 12-1-1940 A Navajo Myth From the Chaco Canyon Gretchen Chapin Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nm_anthropologist Recommended Citation Chapin, Gretchen. "A Navajo Myth From the Chaco Canyon." New Mexico Anthropologist 4, 4 (1940): 63-67. https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nm_anthropologist/vol4/iss4/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Anthropology at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Anthropologist by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NEW MEXICO ANTHROPOLOGIST 63 from the Dominican monastery until 1575. The Real y Pontificia Universidad de Mexico lasted without much interruption until the period of the French Intervention. Then it was closed for many years; became the Universidad Nacional de Mexico in 1910; and in 1929 was chartered as the Universidad Nacional Aut6noma de Mexico.. The University of Lima became the Universidad Mayor de San Marcos de Lima in 1574, and has continued ever since, with major interruptions only during the War for Independence and again just a few years ago. In final summary one can say that, of the New World institutions of higher learning, the College of Santa Cruz was first founded and opened; the University of Michoacin has had the longest history; the University of Lima probably has been open the most years, has been at her present site longest, and has retained present form of name longest; and the University of Mexico has had the greatest number of students, graduates, and faculty members and was the first to actually open of the formally constituted universities. -

Interpretation and Visitor Experience at Chaco Culture National Historic Park Maren Else Svare

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Anthropology ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 7-1-2015 Speaking in Circles: Interpretation and Visitor Experience at Chaco Culture National Historic Park Maren Else Svare Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/anth_etds Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Svare, Maren Else. "Speaking in Circles: Interpretation and Visitor Experience at Chaco Culture National Historic Park." (2015). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/anth_etds/69 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maren Else Svare Candidate Anthropology Department This thesis is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Thesis Committee: Dr. Ronda Brulotte, Chairperson Dr. Erin Debenport Dr. Loa Traxler i SPEAKING IN CIRCLES: INTERPRETATION AND VISITOR EXPERIENCE AT CHACO CULTURE NATIONAL HISTORIC PARK by MAREN ELSE SVARE BACHELOR OF ANTHROPOLOGY THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Anthropology The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico May, 2015 ii Acknowledgments This thesis could have been completed without the wisdom, support, and diligence of my committee. Thank you to my committee chair, Dr. Ronda Brulotte, for consistently and patiently guiding me to rethink and rework. Dr. Erin Debenport supplied both good humor and good advice, keeping my expectations realistic and my writing on track. I am grateful to Dr. -

Chaco Culture

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Chaco Culture Chaco Culture N.H.P. Chaco Canyon Place Names In 1849, Lieutenant James Simpson, a member of the Washington Expedition, surveyed many areas throughout the Southwest. He described and reported on many ancestral Puebloan and Navajo archaeological sites now associated with Chaco Culture NHP. Simpson used the names given to him by Carravahal, a local guide, for many of the sites. These are the names that we use today. However, the Pueblo Peoples of NM, the Hopi of AZ, and the Navajo, have their own names for many of these places. Some of these names have been omitted due to their sacred and non-public nature. Many of the names listed here are Navajo since the Navajo have lived in the canyon most recently and continue to live in the area. These names often reveal how the Chacoan sites have been incorporated into the culture, history, and oral histories of the Navajo people. There are also different names for the people who lived here 1,000 years ago. The people who lived in Chaco were probably diverse groups of people. “Anasazi” is a Navajo word which translates to “ancient ones” or “ancient enemies.” Today, we refer to this group as the “Ancestral Puebloans” because many of the descendents of Chaco are the Puebloan people. However there are many groups that speak their own languages and have their own names for the ancient people here. “Ancestral Puebloans” is a general term that accounts for this. Chaco-A map drawn in 1776 by Spanish cartographer, Bernardo de Pacheco identifies this area as “Chaca” which is a Spanish colonial word commonly used to mean “a large expanse of open and unexplored land, desert, plain, or prairie.” The term “Chaca” is believed to be the origin of both the word Chacra in reference to Chacra Mesa and Chaco. -

The Chaco Phenomenon

The Chaco CROW CANYON Phenomenon ARCHAEOLOGICAL CENTER September 24–30, 2017 ITINERARY SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 24 Arrive in Durango, Colorado, by 4 p.m. Meet the group for dinner and program orientation. Our scholar, Erin Baxter, Ph.D., provides an overview of the movements of Chaco culture, as well as the latest research. Overnight, Durango. D MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 25 Drive south to Chaco Culture National Historical Park, in the high desert of what is now northern New Mexico. From about A.D. 900 to 1150, Chaco Canyon was the center of a vast regional system that integrated much of the Pueblo world. Our Chaco Canyon exploration begins with the great houses of “downtown” Chaco. At Chetro Ketl and Pueblo Bonito, we examine the architectural features that define great houses and discuss current theories about their function in the community. With the transformation of Pueblo Bonito into the largest of all great houses, some believe Chaco Canyon became the center of the ancestral Pueblo world. We meander along the cliffs on the north side of the canyon, searching for rock art. Overnight, camping under the stars, Chaco Canyon. B L D TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 26 This morning we explore the great houses, great kivas, and small house sites of Tsin Kletsin in Chaco Canyon (2.5 mile round-trip hike, 450-foot Chetro Ketl elevation change). We also visit Casa Rinconada and associated small house sites. Though small house sites are contemporaneous with great houses, the architecture differs markedly, and we discuss the meaning of these differences. After some time at the visitor center, we take the short hike to Una Vida and nearby rock art. -

The Archaeology of Chaco Canyon

The Archaeology of Chaco Canyon Chaco Matters An Introduction Stephen H. Lekson Chaco Canyon, in northwestern New Mexico, was a great Pueblo center of the eleventh and twelfth centuries A.D. (figures 1.1 and 1.2; refer to plate 2). Its ruins represent a decisive time and place in the his- tory of “Anasazi,” or Ancestral Pueblo peoples. Events at Chaco trans- formed the Pueblo world, with philosophical and practical implications for Pueblo descendents and for the rest of us. Modern views of Chaco vary: “a beautiful, serene place where everything was provided by the spirit helpers” (S. Ortiz 1994:72), “a dazzling show of wealth and power in a treeless desert” (Fernandez-Armesto 2001:61), “a self-inflicted eco- logical disaster” (Diamond 1992:332). Chaco, today, is a national park. Despite difficult access (20 miles of dirt roads), more than seventy-five thousand people visit every year. Chaco is featured in compendiums of must-see sights, from AAA tour books, to archaeology field guides such as America’s Ancient Treasures (Folsom and Folsom 1993), to the Encyclopedia of Mysterious Places (Ingpen and Wilkinson 1990). In and beyond the Southwest, Chaco’s fame manifests in more substantial, material ways. In Albuquerque, New Mexico, the structure of the Pueblo Indian Cultural COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL 3 Stephen H. Lekson Figure 1.1 The Chaco region. Center mimics precisely Pueblo Bonito, the most famous Chaco ruin. They sell Chaco (trademark!) sandals in Paonia, Colorado, and brew Chaco Canyon Ale (also trademark!) in Lincoln, Nebraska. The beer bottle features the Sun Dagger solstice marker, with three beams of light striking a spiral petroglyph, presumably indicating that it is five o’clock somewhere. -

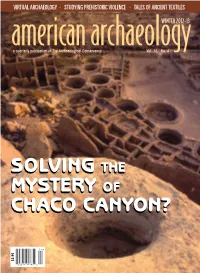

Solving the Mystery of Chaco Canyon?

VIRTUALBANNER ARCHAEOLOGY BANNER • BANNER STUDYING • BANNER PREHISTORIC BANNER VIOLENCE BANNER • T •ALE BANNERS OF A NCIENT BANNER TEXTILE S american archaeologyWINTER 2012-13 a quarterly publication of The Archaeological Conservancy Vol. 16 No. 4 SOLVINGSOLVING THETHE MYMYSSTERYTERY OFOF CHACHACCOO CANYONCANYON?? $3.95 $3.95 WINTER 2012-13 americana quarterly publication of The Archaeological archaeology Conservancy Vol. 16 No. 4 COVER FEATURE 26 CHACO, THROUGH A DIFFERENT LENS BY MIKE TONER Southwest scholar Steve Lekson has taken an unconventional approach to solving the mystery of Chaco Canyon. 12 VIRTUALLY RECREATING THE PAST BY JULIAN SMITH Virtual archaeology has remarkable potential, but it also has some issues to resolve. 19 A ROAD TO THE PAST BY ALISON MCCOOK A dig resulting from a highway project is yielding insights into Delaware’s colonial history. 33 THE TALES OF ANCIENT TEXTILES BY PAULA NEELY Fabric artifacts are providing a relatively new line of evidence for archaeologists. 39 UNDERSTANDING PREHISTORIC VIOLENCE BY DAN FERBER Bioarchaeologists have gone beyond studying the manifestations of ancient violence to examining CHAZ EVANS the conditions that caused it. 26 45 new acquisition A TRAIL TO PREHISTORY The Conservancy saves a trailhead leading to an important Sinagua settlement. 46 new acquisition NORTHERNMOST CHACO CANYON OUTLIER TO BE PRESERVED Carhart Pueblo holds clues to the broader Chaco regional system. 48 point acquisition A GLIMPSE OF A MAJOR TRANSITION D LEVY R Herd Village could reveal information about the change from the Basketmaker III to the Pueblo I phase. RICHA 12 2 Lay of the Land 50 Field Notes 52 RevieWS 54 Expeditions 3 Letters 5 Events COVER: Pueblo Bonito is one of the great houses at Chaco Canyon. -

A History Southeastern Archaeological Conference Its Seventy-Fifth Annual Meeting, 2018

A History m of the M Southeastern Archaeological Conference m in celebration of M Its Seventy-Fifth Annual Meeting, 2018 Dedicated to Stephen Williams: SEAC Stalwart Charles H. McNutt 1928–2017 Copyright © 2018 by SEAC Printed by Borgo Publishing for the Southeastern Archaeological Conference Copy editing and layout by Kathy Cummins ii Contents Introduction .............................................................................................1 Ancestors ..................................................................................................5 Setting the Agenda:The National Research Council Conferences ....................................................................15 FERACWATVAWPA ............................................................................21 Founding Fathers ...................................................................................25 Let’s Confer !! .........................................................................................35 The Second Meeting ..............................................................................53 Blest Be the Tie That Binds ..................................................................57 The Other Pre-War Conferences .........................................................59 The Post-War Revival ............................................................................65 Vale Haag ................................................................................................73 The CHSA-SEAC Years (1960–1979)..................................................77 -

Ocmulgee National Monument the Earth Lodge Historic Structure Report

Ocmulgee National Monument The Earth Lodge Historic Structure Report August 2005 Historic Architecture, Cultural Resources Division Southeast Regional Office National Park Service The historic structure report presented here exists in two formats. A traditional, printed version is available for study at the park, the Southeastern Regional Office of the NPS (SERO), and at a variety of other repositories. For more widespread access, the historic structure report also exists in a web- based format through ParkNet, the website of the National Park Service. Please visit www.nps.gov for more information. Cultural Resources Southeast Region National Park Service 100 Alabama St. SW Atlanta, GA 30303 (404) 562-3117 2004 Historic Structure Report The Earth Lodge Ocmulgee National Monument Macon, Georgia LCS#: 001186 Cover image: Earth Lodge, c. 1940. (OCMU Coll.) Table of Contents Foreword . xv Project Team xvii Management Summary Historical Data . 1 Architectural Data . 1 Pre-Columbian Features. 1 Reconstructed Features . 2 Interpretation . 3 Summary of Recommendations. 3 Pre-Columbian Features. 3 Reconstructed Features . 4 Visitor Experience. 4 Interpretation . 4 Administrative Data . 4 Locational Data. 4 Related Studies . 5 Cultural Resource Data. 5 Historical Background and Context Ocmulgee Old Fields. 8 Ocmulgee National Monument. 11 Chronology of Development and Use Earth Lodges . 15 Original Construction and Loss . 19 Discovery . 20 Reconstruction . 24 Planning . 25 Construction . 28 Ventilation . 36 Walkway . 36 Compromise . 36 Preservation . 37 Ventilation . 38 Clay Features. 39 Walkway . 43 Research and Interpretation . 43 Fire Protection . 44 Lighting. 44 Entrance . 44 Termites. 46 National Park Service v Sod . .47 Climate Control . .48 Kidd and Associates Study . .49 Mold and Cracks Redux. -

The House of Our Ancestors: New Research on the Prehistory of Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, A.D. 800•Fi1200

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Anthropology Faculty Publications Anthropology, Department of 2015 The ouH se of Our Ancestors: New Research on the Prehistory of Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, A.D. 800–1200 Carrie Heitman University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/anthropologyfacpub Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Indigenous Studies Commons, Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Heitman, Carrie, "The ousH e of Our Ancestors: New Research on the Prehistory of Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, A.D. 800–1200" (2015). Anthropology Faculty Publications. 127. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/anthropologyfacpub/127 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Anthropology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in Chaco Revisited New Research on the Prehistory of Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, ed. Carrie C. Heitman and Stephen Plog. The University of Arizona Press, Tucson, 2015. Pp. 215–248. Copyright 2015 The Arizona Board of Regents. digitalcommons.unl.edu The House of Our Ancestors: New Research on the Prehistory of Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, A.D. 800–1200 Carrie C. Heitman, University of Nebraska–Lincoln In a paper honoring the career of archaeologist Gwinn -

Charles Lindbergh's Contribution to Aerial Archaeology

THE FATES OF ANCIENT REMAINS • SUMMER TRAVEL • SPANISH-INDIGENOUS RELIGIOUS HARMONY american archaeologySUMMER 2017 a quarterly publication of The Archaeological Conservancy Vol. 21 No. 2 Charles Lindbergh’s Contribution To Aerial Archaeology $3.95 US/$5.95 CAN summer 2017 americana quarterly publication of The Archaeological archaeology Conservancy Vol. 21 No. 2 COVER FEATURE 18 CHARLES LINDBERGH’S LITTLE-KNOWN PASSION BY TAMARA JAGER STEWART The famous aviator made important contributions to aerial archaeology. 12 COMITY IN THE CAVES BY JULIAN SMITH Sixteenth-century inscriptions found in caves on Mona Island in the Caribbean suggest that the Spanish respected the natives’ religious expressions. 26 A TOUR OF CIVIL WAR BATTLEFIELDS BY PAULA NEELY ON S These sites serve as a reminder of this crucial moment in America’s history. E SAM C LI A 35 CURING THE CURATION PROBLEM BY TOM KOPPEL The Sustainable Archaeology project in Ontario, Canada, endeavors to preserve and share the province’s cultural heritage. JAGO COOPER AND 12 41 THE FATES OF VERY ANCIENT REMAINS BY MIKE TONER Only a few sets of human remains over 8,000 years old have been discovered in America. What becomes of these remains can vary dramatically from one case to the next. 47 THE POINT-6 PROGRAM BEGINS 48 new acquisition THAT PLACE CALLED HOME OR Dahinda Meda protected Terrarium’s remarkable C E cultural resources for decades. Now the Y S Y Conservancy will continue his work. DD 26 BU 2 LAY OF THE LAND 3 LETTERS 50 FiELD NOTES 52 REVIEWS 54 EXPEDITIONS 5 EVENTS 7 IN THE NEWS COVER: In 1929, Charles and Anne Lindbergh photographed Pueblo • Humans In California 130,000 Years Ago? del Arroyo, a great house in Chaco Canyon.