Absolute and Relative Gas Concentration: Understanding Oxygen in Air

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sanitization: Concentration, Temperature, and Exposure Time

Sanitization: Concentration, Temperature, and Exposure Time Did you know? According to the CDC, contaminated equipment is one of the top five risk factors that contribute to foodborne illnesses. Food contact surfaces in your establishment must be cleaned and sanitized. This can be done either by heating an object to a high enough temperature to kill harmful micro-organisms or it can be treated with a chemical sanitizing compound. 1. Heat Sanitization: Allowing a food contact surface to be exposed to high heat for a designated period of time will sanitize the surface. An acceptable method of hot water sanitizing is by utilizing the three compartment sink. The final step of the wash, rinse, and sanitizing procedure is immersion of the object in water with a temperature of at least 170°F for no less than 30 seconds. The most common method of hot water sanitizing takes place in the final rinse cycle of dishwashing machines. Water temperature must be at least 180°F, but not greater than 200°F. At temperatures greater than 200°F, water vaporizes into steam before sanitization can occur. It is important to note that the surface temperature of the object being sanitized must be at 160°F for a long enough time to kill the bacteria. 2. Chemical Sanitization: Sanitizing is also achieved through the use of chemical compounds capable of destroying disease causing bacteria. Common sanitizers are chlorine (bleach), iodine, and quaternary ammonium. Chemical sanitizers have found widespread acceptance in the food service industry. These compounds are regulated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and consequently require labeling with the word “Sanitizer.” The labeling should also include what concentration to use, data on minimum effective uses and warnings of possible health hazards. -

Lecture 3. the Basic Properties of the Natural Atmosphere 1. Composition

Lecture 3. The basic properties of the natural atmosphere Objectives: 1. Composition of air. 2. Pressure. 3. Temperature. 4. Density. 5. Concentration. Mole. Mixing ratio. 6. Gas laws. 7. Dry air and moist air. Readings: Turco: p.11-27, 38-43, 366-367, 490-492; Brimblecombe: p. 1-5 1. Composition of air. The word atmosphere derives from the Greek atmo (vapor) and spherios (sphere). The Earth’s atmosphere is a mixture of gases that we call air. Air usually contains a number of small particles (atmospheric aerosols), clouds of condensed water, and ice cloud. NOTE : The atmosphere is a thin veil of gases; if our planet were the size of an apple, its atmosphere would be thick as the apple peel. Some 80% of the mass of the atmosphere is within 10 km of the surface of the Earth, which has a diameter of about 12,742 km. The Earth’s atmosphere as a mixture of gases is characterized by pressure, temperature, and density which vary with altitude (will be discussed in Lecture 4). The atmosphere below about 100 km is called Homosphere. This part of the atmosphere consists of uniform mixtures of gases as illustrated in Table 3.1. 1 Table 3.1. The composition of air. Gases Fraction of air Constant gases Nitrogen, N2 78.08% Oxygen, O2 20.95% Argon, Ar 0.93% Neon, Ne 0.0018% Helium, He 0.0005% Krypton, Kr 0.00011% Xenon, Xe 0.000009% Variable gases Water vapor, H2O 4.0% (maximum, in the tropics) 0.00001% (minimum, at the South Pole) Carbon dioxide, CO2 0.0365% (increasing ~0.4% per year) Methane, CH4 ~0.00018% (increases due to agriculture) Hydrogen, H2 ~0.00006% Nitrous oxide, N2O ~0.00003% Carbon monoxide, CO ~0.000009% Ozone, O3 ~0.000001% - 0.0004% Fluorocarbon 12, CF2Cl2 ~0.00000005% Other gases 1% Oxygen 21% Nitrogen 78% 2 • Some gases in Table 3.1 are called constant gases because the ratio of the number of molecules for each gas and the total number of molecules of air do not change substantially from time to time or place to place. -

Carbon Monoxide Levels and Risks

Carbon Monoxide Levels and Risks CO Level Action CO Level Action 0.1 ppm Natural atmosphere level or clean air. 70-75 ppm Heart patients experience an increase in chest pain. Significant decrease in 1 ppm An increase of 1 ppm in the maximum dai- oxygen available to the myocardium/ ly one-hour exposure is associated with a heart (HbCO 10%). 0.96 percent increase in the risk of hospi- 100 ppm Headache, tiredness, dizziness, nausea talization from cardiovascular disease within 2 hrs of exposure. At 5 hrs, dam- among people over the age of 65. age to hearts and brains. (Lewey & Drabkin) (Circulation: Journal of the AHA, Sept, 2009) 200 ppm Healthy adults will have headache, nau- 3-7 ppm 6% increase in the rate of admission in sea at this level. hospitals of non-elderly for asthma. (L. Shep- pard et al.,Epidemiology, Jan 1999) NIOSH & OSHA recommend evacua- tion of the workplace at this level. 5-6 ppm Significant risk of low birth weight if exposed during last trimester - in a study 400 ppm Frontal headache within 1-2 hours—life of 125,573 pregnancies (Ritz & Yu, Environ. threatening within 3 hours. Health Perspectives, 1999). 500 ppm Concentration in a garage when a cold 9 ppm EPA and WHO maximum outdoor air lev- car is started in an open garage and el, all ages, (TWA, 8 hrs). Maximum allow- warmed up for 2 minutes. (Greiner, 1997) able indoor level (ASHRAE) 800 ppm Healthy adults will have nausea, dizzi- Lowest CO level producing significant ef- ness and convulsions within 45 fects on cardiac function (ST-segment minutes. -

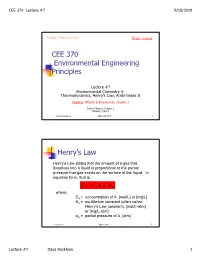

CEE 370 Environmental Engineering Principles Henry's

CEE 370 Lecture #7 9/18/2019 Updated: 18 September 2019 Print version CEE 370 Environmental Engineering Principles Lecture #7 Environmental Chemistry V: Thermodynamics, Henry’s Law, Acids-bases II Reading: Mihelcic & Zimmerman, Chapter 3 Davis & Masten, Chapter 2 Mihelcic, Chapt 3 David Reckhow CEE 370 L#7 1 Henry’s Law Henry's Law states that the amount of a gas that dissolves into a liquid is proportional to the partial pressure that gas exerts on the surface of the liquid. In equation form, that is: C AH = K p A where, CA = concentration of A, [mol/L] or [mg/L] KH = equilibrium constant (often called Henry's Law constant), [mol/L-atm] or [mg/L-atm] pA = partial pressure of A, [atm] David Reckhow CEE 370 L#7 2 Lecture #7 Dave Reckhow 1 CEE 370 Lecture #7 9/18/2019 Henry’s Law Constants Reaction Name Kh, mol/L-atm pKh = -log Kh -2 CO2(g) _ CO2(aq) Carbon 3.41 x 10 1.47 dioxide NH3(g) _ NH3(aq) Ammonia 57.6 -1.76 -1 H2S(g) _ H2S(aq) Hydrogen 1.02 x 10 0.99 sulfide -3 CH4(g) _ CH4(aq) Methane 1.50 x 10 2.82 -3 O2(g) _ O2(aq) Oxygen 1.26 x 10 2.90 David Reckhow CEE 370 L#7 3 Example: Solubility of O2 in Water Background Although the atmosphere we breathe is comprised of approximately 20.9 percent oxygen, oxygen is only slightly soluble in water. In addition, the solubility decreases as the temperature increases. -

Pressure Vs. Volume and Boyle's

Pressure vs. Volume and Boyle’s Law SCIENTIFIC Boyle’s Law Introduction In 1642 Evangelista Torricelli, who had worked as an assistant to Galileo, conducted a famous experiment demonstrating that the weight of air would support a column of mercury about 30 inches high in an inverted tube. Torricelli’s experiment provided the first measurement of the invisible pressure of air. Robert Boyle, a “skeptical chemist” working in England, was inspired by Torricelli’s experiment to measure the pressure of air when it was compressed or expanded. The results of Boyle’s experiments were published in 1662 and became essentially the first gas law—a mathematical equation describing the relationship between the volume and pressure of air. What is Boyle’s law and how can it be demonstrated? Concepts • Gas properties • Pressure • Boyle’s law • Kinetic-molecular theory Background Open end Robert Boyle built a simple apparatus to measure the relationship between the pressure and volume of air. The apparatus ∆h ∆h = 29.9 in. Hg consisted of a J-shaped glass tube that was Sealed end 1 sealed at one end and open to the atmosphere V2 = /2V1 Trapped air (V1) at the other end. A sample of air was trapped in the sealed end by pouring mercury into Mercury the tube (see Figure 1). In the beginning of (Hg) the experiment, the height of the mercury Figure 1. Figure 2. column was equal in the two sides of the tube. The pressure of the air trapped in the sealed end was equal to that of the surrounding air and equivalent to 29.9 inches (760 mm) of mercury. -

Worksheet 6 Solutions MATH 1A Fall 2015

Worksheet 6 Solutions MATH 1A Fall 2015 for 27 October 2015 These problems are taken from a set of science problems for calculus written by Jim Belk, avail- able at math.bard.edu/belk/writing.htm. If you’re looking for more practice on related rates or exponential growth, check it out! His problems are less terminally boring than the textbook’s problems. Exercise 6.1. In chemistry and physics, Boyle’s Law describes the relationship between the pressure and volume of a fixed quantity of gas maintained at a constant temperature. The law states that: PV = a constant where P is the pressure of the gas, and V is the volume. dP dV 1. Take the derivative of Boyle’s law to find an equation relating , , P, and V. dt dt 2. A sample of gas is placed in a cylindrical piston. At the beginning of the experiment, the gas occupies a volume of 250 cm3, and has a pressure of 100 kPa. The piston is slowly compressed, decreasing the volume of the gas at a rate of 50 cm3/min. How quickly will the pressure of the gas initially increase? Solution. For the first question, by taking an implicit derivative (using the product rule on the left hand side) we find dP dV V + P = 0. dt dt For the second question, we simply plug the values provided into the equation we’ve just found, dP (250) + (100)(50) = 0, dt dP and solve to find dt = 20 kPa/min. Exercise 6.2. In chemistry, the pH of a solution is defined by the formula pH = −0.4343 ln(a), where a is the hydrogen ion activity (a measure of the “effective concentration” of hydrogen ions). -

Influence of Hydrophobe Fraction Content on the Rheological Properties of Hydrosoluble Associative Polymers Obtained by Micellar Polymerization

http://www.e-polymers.org e-Polymers 2012, no. 009 ISSN 1618-7229 Influence of hydrophobe fraction content on the rheological properties of hydrosoluble associative polymers obtained by micellar polymerization Enrique J. Jiménez-Regalado,1* Elva B. Hernández-Flores2 1Centro de Investigación en Química Aplicada (CIQA) Blvd. Enrique Reyna #140, 25253, Saltillo, Coahuila, México; e-mail: [email protected] bCentro de Investigación en Química Aplicada (CIQA) Blvd. Enrique Reyna #140, 25253, Saltillo, Coahuila, México; e-mail: [email protected] (Received: 20 November, 2009; published: 22 January, 2012) Abstract: The synthesis, characterization and rheological properties in aqueous solutions of water-soluble associative polymers (AP’s) are reported. Polymer chains consisting of water-soluble polyacrylamides, hydrophobically modified with low amounts of N,N-dihexylacrylamide (1, 2, 3 and 4 mol%) were prepared via free radical micellar polymerization. The properties of these polymers, with respect to the concentration of hydrophobic groups, using steady-flow and oscillatory experiments were compared. An increase of relaxation time (TR) and modulus plateau (G0) was observed in all samples studied. Two different regimes can be clearly distinguished: a first unentangled regime where the viscosity increase rate strongly depends on hydrophobic content and a second entangled regime where the viscosity follows a scaling behavior of the polymer concentration with an exponent close to 4. Introduction Water-soluble polymers are of great interest from the scientific as well as the technological point of view. These polymers have been subjected to extensive research [1]. Water-soluble polymers are present in the composition of different types of industrial formulations as stabilizing, flocculants, absorbent, emulsifiers, thickeners, etc. -

The Small-Molecule BGP-15 Protects Against Heart Failure and Atrial fibrillation in Mice

ARTICLE Received 15 Sep 2014 | Accepted 30 Oct 2014 | Published 9 Dec 2014 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms6705 The small-molecule BGP-15 protects against heart failure and atrial fibrillation in mice Geeta Sapra1,*, Yow Keat Tham1,*, Nelly Cemerlang1, Aya Matsumoto1, Helen Kiriazis1, Bianca C. Bernardo1, Darren C. Henstridge1, Jenny Y.Y. Ooi1, Lynette Pretorius1,2, Esther J.H. Boey1, Lydia Lim1, Junichi Sadoshima3, Peter J. Meikle1, Natalie A. Mellet1, Elizabeth A. Woodcock1, Silvana Marasco4, Tomomi Ueyama5, Xiao-Jun Du1, Mark A. Febbraio1,2 & Julie R. McMullen1,2 Heart failure (HF) and atrial fibrillation (AF) share common risk factors, frequently coexist and are associated with high mortality. Treatment of HF with AF represents a major unmet need. Here we show that a small molecule, BGP-15, improves cardiac function and reduces arrhythmic episodes in two independent mouse models, which progressively develop HF and AF. In these models, BGP-15 treatment is associated with increased phosphorylation of the insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF1R), which is depressed in atrial tissue samples from patients with AF. Cardiac-specific IGF1R transgenic overexpression in mice with HF and AF recapitulates the protection observed with BGP-15. We further demonstrate that BGP-15 and IGF1R can provide protection independent of phosphoinositide 3-kinase-Akt and heat-shock protein 70; signalling mediators often defective in the aged and diseased heart. As BGP-15 is safe and well tolerated in humans, this study uncovers a potential therapeutic approach for HF and AF. 1 Baker IDI Heart and Diabetes Institute, PO Box 6492, Melbourne, Victoria 3004, Australia. 2 Monash University, Melbourne, Victoria 3800, Australia. -

Concentration and Fractionation of Hydrophobic Organic Acid Constituents from Natural Waters by Liquid Chromatography

Concentration and Fractionation of Hydrophobic Organic Acid Constituents from Natural Waters by Liquid Chromatography GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1817-G Concentration and Fractionation of Hydrophobic Organic Acid Constituents from Natural Waters by Liquid Chromatography By E. M. THURMAN and R. L. MALCOLM ORGANIC SUBSTANCES INW^TER GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1817-G UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1979 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR CECIL D. ANDRUS, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY H. William Menard, Director Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Thurman, Earl M. Concentration and fractionation of hydrophobic organic acid constituents from natural waters by liquid chromatography. (Organic substances in water) (Geological Survey water-supply paper 1817-G) Bibliography: p. 15, 16. Supt.ofDocs.no.: I 19.13:1817-G 1. Acids, Organic. 2. Liquid chromatography. 3. Water chemistry. I. Malcolm, R. L., joint author. II. Title. III. Series. IV. Series: United States. Geological Survey. Water-supply paper ; 1817-G. TC801.U2 no. 1817-G [QD305.A2] 553'.7'0973s 79-607114 [628.1'61] For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington, D. C. 20402 Stock Number 024-001-03226-1 CONTENTS Page Abstract _____________________________________---_--___-___Gl Introduction ________-_____________________________________ 1 Acknowledgments _____________________________ 2 Experimental procedures ______________________________________ 2 Resin and column packings _________________________________ -

Kinetics of Plasma Cytokines, Angiopoietin-2, and C-Reactive Protein in Dogs with Gastric Dilatation Volvulus

ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 16 June 2021 doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.652479 Kinetics of Plasma Cytokines, Angiopoietin-2, and C-Reactive Protein in Dogs With Gastric Dilatation Volvulus Anna Brunner 1, Simone Schuller 2, Bianca Hettlich 1, Eliane Marti 3, Anna Lehmann 2, Laureen M. Peters 4 and Katja-Nicole Adamik 5* 1 Division of Small Animal Surgery, Department of Clinical Veterinary Science, Vetsuisse Faculty, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland, 2 Division of Small Animal Internal medicine, Department of Clinical Veterinary Science, Vetsuisse Faculty, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland, 3 Department of Clinical Research and Veterinary Public Health, Vetsuisse Faculty, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland, 4 Clinical Diagnostic Laboratory, Department of Clinical Veterinary Science, Vetsuisse Faculty, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland, 5 Division of Small Animal Emergency and Critical Care, Department of Clinical Veterinary Science, Vetsuisse Faculty, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland Edited by: Maureen Ann McMichael, Background: The degree of systemic inflammation, reperfusion injury and endothelial Auburn University, United States activation are potentially important determinants of clinical outcomes in dogs with gastric Reviewed by: dilatation volvulus (GDV). Rene Doerfelt, Ludwig-Maximilians Universität Objective: To evaluate plasma concentrations and kinetics of inflammatory markers in München, Germany dogs with GDV over a time frame of 48 h, and to compare to healthy dogs. Thomas H. Edwards, United States Army Institute of Design and Setting: Prospective, observational cohort study in client-owned dogs Surgical Research, United States with GDV. *Correspondence: Katja-Nicole Adamik Materials and Methods: Fifteen dogs with GDV and 9 healthy control dogs [email protected] were enrolled. -

Raoult's Law – Partition Law

BAE 820 Physical Principles of Environmental Systems Henry’s Law - Raoult's Law – Partition law Dr. Zifei Liu Biological and Agricultural Engineering Henry's law • At a constant temperature, the amount of a given gas that dissolves in a given type and volume of liquid is directly proportional to the partial pressure of that gas in equilibrium with that liquid. Pi = KHCi • Where Pi is the partial pressure of the gaseous solute above the solution, C is the i William Henry concentration of the dissolved gas and KH (1774-1836) is Henry’s constant with the dimensions of pressure divided by concentration. KH is different for each solute-solvent pair. Biological and Agricultural Engineering 2 Henry's law For a gas mixture, Henry's law helps to predict the amount of each gas which will go into solution. When a gas is in contact with the surface of a liquid, the amount of the gas which will go into solution is proportional to the partial pressure of that gas. An equivalent way of stating the law is that the solubility of a gas in a liquid is directly proportional to the partial pressure of the gas above the liquid. the solubility of gases generally decreases with increasing temperature. A simple rationale for Henry's law is that if the partial pressure of a gas is twice as high, then on the average twice as many molecules will hit the liquid surface in a given time interval, Biological and Agricultural Engineering 3 Air-water equilibrium Dissolution Pg or Cg Air (atm, Pa, mol/L, ppm, …) At equilibrium, Pg KH = Caq Water Caq (mol/L, mole ratio, ppm, …) Volatilization Biological and Agricultural Engineering 4 Various units of the Henry’s constant (gases in water at 25ºC) Form of K =P/C K =C /P K =P/x K =C /C equation H, pc aq H, cp aq H, px H, cc aq gas Units L∙atm/mol mol/(L∙atm) atm dimensionless -3 4 -2 O2 769 1.3×10 4.26×10 3.18×10 -4 4 -2 N2 1639 6.1×10 9.08×10 1.49×10 -2 3 CO2 29 3.4×10 1.63×10 0.832 Since all KH may be referred to as Henry's law constants, we must be quite careful to check the units, and note which version of the equation is being used. -

Effects of Hydrophobic Chain Length on the Micelles of Heptaoxyethylene Hexadecyl C16E7 and Octadecyl C18E7 Ethers

Polymer Journal, Vol. 37, No. 5, pp. 368–375 (2005) Effects of Hydrophobic Chain Length on the Micelles of Heptaoxyethylene Hexadecyl C16E7 and Octadecyl C18E7 Ethers y Yoshiyuki EINAGA, Ai KUSUMOTO, and Akane NODA Department of Chemistry, Nara Women’s University, Kitauoya Nishi-machi, Nara 630-8506, Japan (Received January 4, 2005; Accepted February 1, 2005; Published May 15, 2005) ABSTRACT: Micelles of heptaoxyethylene hexadecyl C16E7 and octadecyl C18E7 ethers in dilute aqueous solu- tions were characterized at finite surfactant concentrations c by static (SLS) and dynamic light scattering (DLS) experi- ments at several temperatures T below the critical points, in order to examine the effects of hydrophobic chain length on size, shape, structure, etc., of the micelles. The SLS results were successfully analyzed by the thermodynamic theory formulated with wormlike spherocylinder model for SLS of micelle solutions, thereby yielding the molar mass Mw of the micelles as a function of c and the cross-sectional diameter d, indicating that the micelles assume a flexible spher- 2 1=2 ocylindrical shape. The radius of gyration hS i and hydrodynamic radius RH of the micelles as functions of Mw were found to be also well described by the corresponding theories for the wormlike spherocylinder or wormlike chain mod- els. The micelles grow in size with increasing T to greater length for longer hydrophobic chain, i.e., alkyl group of the surfactants. They were rather flexible compared to the micelles formed with other polyoxyethylen alkyl ethers. The cross-sectional diameter d and spacings s between adjacent hexaoxyethylene chains on the micellar surface were sim- ilar in the C16E7 and C18E7 micelles.