Caddo Archeology Journal, Volume

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Further Investigations Into the King George

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2010 Further investigations into the King George Island Mounds site (16LV22) Harry Gene Brignac Jr Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Brignac Jr, Harry Gene, "Further investigations into the King George Island Mounds site (16LV22)" (2010). LSU Master's Theses. 2720. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2720 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FURTHER INVESTIGATIONS INTO THE KING GEORGE ISLAND MOUNDS SITE (16LV22) A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of Geography and Anthropology By Harry Gene Brignac Jr. B.A. Louisiana State University, 2003 May, 2010 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I would like to give thanks to God for surrounding me with the people in my life who have guided and supported me in this and all of my endeavors. I have to express my greatest appreciation to Dr. Rebecca Saunders for her professional guidance during this entire process, and for her inspiration and constant motivation for me to become the best archaeologist I can be. -

Travel Summary

Travel Summary – All Trips and Day Trips Retirement 2016-2020 Trips (28) • Relatives 2016-A (R16A), September 30-October 20, 2016, 21 days, 441 photos • Anza-Borrego Desert 2016-A (A16A), November 13-18, 2016, 6 days, 711 photos • Arizona 2017-A (A17A), March 19-24, 2017, 6 days, 692 photos • Utah 2017-A (U17A), April 8-23, 2017, 16 days, 2214 photos • Tonopah 2017-A (T17A), May 14-19, 2017, 6 days, 820 photos • Nevada 2017-A (N17A), June 25-28, 2017, 4 days, 515 photos • New Mexico 2017-A (M17A), July 13-26, 2017, 14 days, 1834 photos • Great Basin 2017-A (B17A), August 13-21, 2017, 9 days, 974 photos • Kanab 2017-A (K17A), August 27-29, 2017, 3 days, 172 photos • Fort Worth 2017-A (F17A), September 16-29, 2017, 14 days, 977 photos • Relatives 2017-A (R17A), October 7-27, 2017, 21 days, 861 photos • Arizona 2018-A (A18A), February 12-17, 2018, 6 days, 403 photos • Mojave Desert 2018-A (M18A), March 14-19, 2018, 6 days, 682 photos • Utah 2018-A (U18A), April 11-27, 2018, 17 days, 1684 photos • Europe 2018-A (E18A), June 27-July 25, 2018, 29 days, 3800 photos • Kanab 2018-A (K18A), August 6-8, 2018, 3 days, 28 photos • California 2018-A (C18A), September 5-15, 2018, 11 days, 913 photos • Relatives 2018-A (R18A), October 1-19, 2018, 19 days, 698 photos • Arizona 2019-A (A19A), February 18-20, 2019, 3 days, 127 photos • Texas 2019-A (T19A), March 18-April 1, 2019, 15 days, 973 photos • Death Valley 2019-A (D19A), April 4-5, 2019, 2 days, 177 photos • Utah 2019-A (U19A), April 19-May 3, 2019, 15 days, 1482 photos • Europe 2019-A (E19A), July -

Elemental Analysis of Marksville-Style Prehistoric Ceramics from Mississippi and Alabama

Mississippi State University Scholars Junction Theses and Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 5-1-2008 Elemental analysis of Marksville-style prehistoric ceramics from Mississippi and Alabama Keith A. Baca Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsjunction.msstate.edu/td Recommended Citation Baca, Keith A., "Elemental analysis of Marksville-style prehistoric ceramics from Mississippi and Alabama" (2008). Theses and Dissertations. 1858. https://scholarsjunction.msstate.edu/td/1858 This Graduate Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Scholars Junction. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholars Junction. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ELEMENTAL ANALYSIS OF MARKSVILLE-STYLE PREHISTORIC CERAMICS FROM MISSISSIPPI AND ALABAMA By Keith Allen Baca A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Mississippi State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Applied Anthropology in the Department of Sociology, Anthropology, and Social Work Mississippi State, Mississippi May 3, 2008 ELEMENTAL ANALYSIS OF MARKSVILLE-STYLE PREHISTORIC CERAMICS FROM MISSISSIPPI AND ALABAMA By Keith Allen Baca Approved: Janet Rafferty Evan Peacock Graduate Coordinator of Anthropology Associate Professor of Anthropology Professor of Anthropology (Director of Thesis) S. Homes Hogue Gary Myers Professor of Anthropology Interim Dean of College of Arts and Sciences Name: Keith Allen Baca Date of Degree: May 3, 2008 Institution: Mississippi State University Major Field: Applied Anthropology Major Professor: Dr. Janet Rafferty Title of Study: ELEMENTAL ANALYSIS OF MARKSVILLE-STYLE PREHISTORIC CERAMICS FROM MISSISSIPPI AND ALABAMA Pages in Study: 129 Candidate for Degree of Master of Arts Distinctive Marksville-style pottery is characteristic of the Middle Woodland period (200 B.C. -

University of Oklahoma

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE ALTERNATE PATHWAYS TO RITUAL POWER: EVIDENCE FOR CENTRALIZED PRODUCTION AND LONG-DISTANCE EXCHANGE BETWEEN NORTHERN AND SOUTHERN CADDO COMMUNITIES A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By SHAWN PATRICK LAMBERT Norman, Oklahoma 2017 ALTERNATE PATHWAYS TO RITUAL POWER: EVIDENCE FOR CENTRALIZED PRODUCTION AND LONG-DISTANCE EXCHANGE BETWEEN NORTHERN AND SOUTHERN CADDO COMMUNITIES A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY BY ______________________________ Dr. Patrick Livingood, Chair ______________________________ Dr. Asa Randall ______________________________ Dr. Amanda Regnier ______________________________ Dr. Scott Hammerstedt ______________________________ Dr. Diane Warren ______________________________ Dr. Bonnie Pitblado ______________________________ Dr. Michael Winston © Copyright by SHAWN PATRICK LAMBERT 2017 All Rights Reserved. Dedication I dedicate my dissertation to my loving grandfather, Calvin McInnish and wonderful twin sister, Kimberly Dawn Thackston. I miss and love you. Acknowledgements First and foremost, I want to give my sincerest gratitude to Patrick Livingood, my committee chair, who has guided me through seven years of my masters and doctoral work. I could not wish for a better committee chair. I also want to thank Amanda Regnier and Scott Hammerstedt for the tremendous amount of work they put into making me the best possible archaeologist. I would also like to thank Asa Randall. His level of theoretical insight is on another dimensional plane and his Advanced Archaeological Theory class is one of the best I ever took at the University of Oklahoma. I express appreciation to Bonnie Pitblado, not only for being on my committee but emphasizing the importance of stewardship in archaeology. -

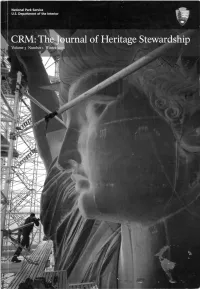

CRM: the Journal of Heritage Stewardship Volume 3 Number I Winter 2006 Editorial Board Contributing Editors

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior CRM: The Journal of Heritage Stewardship Volume 3 Number i Winter 2006 Editorial Board Contributing Editors David G. Anderson, Ph.D. Megan Brown Department of Anthropology, Historic Preservation Grants, University of Tennessee National Park Service Gordon W. Fulton Timothy M. Davis, Ph.D. National Park Service National Historic Sites Park Historic Structures and U.S. Department of the Interior Directorate, Parks Canada Cultural Landscapes, National Park Service Cultural Resources Art Gomez, Ph.D. Intermountain Regional Elaine Jackson-Retondo, Gale A. Norton Office, National Park Service Ph.D. Secretary of the Interior Pacific West Regional Office, Michael Holleran, Ph.D. National Park Service Fran P. Mainella Department of Planning and Director, National Park Design, University of J. Lawrence Lee, Ph.D., P.E. Service Colorado, Denver Heritage Documentation Programs, Janet Snyder Matthews, Elizabeth A. Lyon, Ph.D. National Park Service Ph.D. Independent Scholar; Former Associate Director, State Historic Preservation Barbara J. Little, Ph.D. Cultural Resources Officer, Georgia Archeological Assistance Programs, Frank G. Matero, Ph.D. National Park Service Historic Preservation CRM: The Journal of Program, University of David Louter, Ph.D. Heritage Stewardship Pennsylvania Pacific West Regional Office, National Park Service Winter 2006 Moises Rosas Silva, Ph.D. ISSN 1068-4999 Instutito Nacional de Chad Randl Antropologia e Historia, Heritage Preservation Sue Waldron Mexico Service, Publisher National Park Service Jim W Steely Dennis | Konetzka | Design SWCA Environmental Daniel J. Vivian Group, LLC Consultants, Phoenix, National Register of Historic Design Arizona Places/National Historic Landmarks, Diane Vogt-O'Connor National Park Service National Archives and Staff Records Administration Antoinette J. -

Feasting and Communal Ritual in the Lower Mississippi Valley, Ad 700–1000

FEASTING AND COMMUNAL RITUAL IN THE LOWER MISSISSIPPI VALLEY, AD 700–1000 Megan Crandal Kassabaum A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Anthropology. Chapel Hill 2014 Approved by: Vincas P. Steponaitis C. Margaret Scarry Dale L. Hutchinson Brett H. Riggs Valerie Lambert © 2014 Megan Crandal Kassabaum ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Megan Crandal Kassabaum: Feasting and Communal Ritual in the Lower Mississippi Valley, AD 700–1000 (Under the direction of Vincas P. Steponaitis) This dissertation examines prehistoric activity at the Feltus site (22Je500) in Jefferson County, Mississippi, to elucidate how Coles Creek (AD 700–1200) platform mound sites were used. Data from excavations undertaken by the Feltus Archaeological Project from 2006 to 2012 support the conclusion that Coles Creek people utilized Feltus episodically for some 400 years, with little evidence of permanent habitation. More specifically, the ceramic, floral, and faunal data suggest that Feltus provided a location for periodic ritual events focused around food consumption, post-setting, and mound building. The rapidity with which the middens at Feltus were deposited and the large size of the ceramic vessels implies that the events occurring there brought together large groups of people for massive feasting episodes. The vessel form assemblage is dominated by open bowls and thus suggests an emphasis on food consumption, with less evidence for food preparation and virtually none for food storage. Overall, the ceramic assemblage emphasizes a great deal of continuity in the use of the Feltus landscape from the earliest occupation, during the Hamilton Ridge phase, through the latest, during the Balmoral phase. -

Occupation Sequence at Avery Island. Sherwood Moneer Gagliano Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1967 Occupation Sequence at Avery Island. Sherwood Moneer Gagliano Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Gagliano, Sherwood Moneer, "Occupation Sequence at Avery Island." (1967). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 1248. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/1248 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 67-8779 GAGLIANO, Sherwood Moneer, 1935- OCCUPATION SEQUENCE AT AVERY ISLAND. Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Ph.D., 1967 Anthropology University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan Sherwood Moneer Gagliano 1967 All Rights Reserved OCCUPATION SEQUENCE AT AVERY ISLAND A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Geography and Anthropology by Sherwood Moneer Gagliano B.S., Louisiana State University, 1959 M.A., Louisiana State University, 19&3 January, 1967 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT 'The funds, labor, and other facilities which made this study possible were provided by Avery Island Inc, Many individuals contributed. Drs. James Morgan, and James Coleman, and Messrs. William Smith, Karl LaPleur, Rodney Adams, Stephen Murray, Roger Saucier, Richard Warren, and David Morgan aided in the boring program and excavations. -

O?-A BIBLIOGRAPHY of GLASS TRADE BEADS in NORTH AMERICA

A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF GLASS TRADE BEADS IN NORTH AMERICA Karlis Karklins and Roderick Sprague Originally published in 1980, and long out of print, this bibliography is reproduced here as it continues to be a valuable research tool for the archaeologist, material culture researcher, museologist, and serious collector. Although some of the references are out-of-date, the majority contain information that is still very useful to those seeking comparative archaeological data on trade beads. The bibliography contains 455 annotated entries that deal primarily with glass beads recovered from archaeological contexts in Canada, the United States, and Mexico. A number of works that deal with bead manufacturing techniques, bead classification systems, and other related topics are also included. An index arranged by political unit, temporal range, and other categories adds to the usefulness of the bibliography. INTRODUCTION Since a thorough review of pertinent literature is prerequisite to the meaningful study of a specific artifact category, this bibliography is offered as an aid to those who are carrying out research on glass trade beads found in the continental United States, Canada, and Mexico. The references in this bibliography are primarily those which will be useful in dating bead collections, establishing bead chronologies, and compiling distribution charts of individual bead types. However, references dealing with bead manufacturing techniques, beadwork, bead classification systems, and the historical uses and values of trade beads have also been listed. Some sources dealing with beads from areas outside North America have been included because they have a definite bearing on the study of glass beads in North America. -

Archeology of the Funeral Mound, Ocmulgee National Monument, Georgia

1.2.^5^-3 rK 'rm ' ^ -*m *~ ^-mt\^ -» V-* ^JT T ^T A . ESEARCH SERIES NUMBER THREE Clemson Universii akCHEOLOGY of the FUNERAL MOUND OCMULGEE NATIONAL MONUMENT, GEORGIA TIONAL PARK SERVICE • U. S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR 3ERAL JCATK5N r -v-^tfS i> &, UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Fred A. Seaton, Secretary National Park Service Conrad L. Wirth, Director Ihis publication is one of a series of research studies devoted to specialized topics which have been explored in con- nection with the various areas in the National Park System. It is printed at the Government Printing Office and may be purchased from the Superintendent of Documents, Government Printing Office, Washington 25, D. C. Price $1 (paper cover) ARCHEOLOGY OF THE FUNERAL MOUND OCMULGEE National Monument, Georgia By Charles H. Fairbanks with introduction by Frank M. Settler ARCHEOLOGICAL RESEARCH SERIES NUMBER THREE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U. S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR • WASHINGTON 1956 THE NATIONAL PARK SYSTEM, of which Ocmulgee National Monument is a unit, is dedi- cated to conserving the scenic, scientific, and his- toric heritage of the United States for the benefit and enjoyment of its people. Foreword Ocmulgee National Monument stands as a memorial to a way of life practiced in the Southeast over a span of 10,000 years, beginning with the Paleo-Indian hunters and ending with the modern Creeks of the 19th century. Here modern exhibits in the monument museum will enable you to view the panorama of aboriginal development, and here you can enter the restoration of an actual earth lodge and stand where forgotten ceremonies of a great tribe were held. -

An Intensive Surface Collection and Intrasite Spatial Analysis of the Archaeological Materials from the Coy Mound Site (3LN20), Central Arkansas

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 4-2004 An Intensive Surface Collection and Intrasite Spatial Analysis of the Archaeological Materials from the Coy Mound Site (3LN20), Central Arkansas William Glenn Hill Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Hill, William Glenn, "An Intensive Surface Collection and Intrasite Spatial Analysis of the Archaeological Materials from the Coy Mound Site (3LN20), Central Arkansas" (2004). Master's Theses. 3873. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/3873 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN INTENSIVE SURFACE COLLECTION AND INTRASITE SPATIAL ANALYSIS OF THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL MATERIALS FROM THE COY MOUND SITE (3LN20), CENTRAL ARKANSAS by William Glenn Hill A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degreeof Master of Arts Department of Anthropology WesternMichigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan April 2004 Copyright by William Glenn Hill 2004 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Foremost, my pursuit in archaeology would be less meaningful without the accomplishments of Dr. Randall McGuire, Dr. H. Martin Wobst, and Dr. Michael Nassaney. They have provided a theoretical perspective in archaeology that has integrated and given greater meaning to my own social and archaeological interests. I would especially like to especially thank my thesis advisor, Dr. Michael Nassaney, for the stimulating opportunity to explore research within this theoretical perspective, and my other committee members, Dr. -

Identifying Patterns in Coles Creek Mortuary Data

LOOKING BEYOND THE OBVIOUS: IDENTIFYING PATTERNS IN COLES CREEK MORTUARY DATA Megan C. Kassabaum mound-building and burial practices; (2) investigate whether meaningful patterns exist in the burials from Greenhouse (16AV2), Lake George (22YZ557), and Mount Nebo (16MA18); and (3) offer suggestions as While the lack of grave goods has been the focus of most to how the results of my analyses can be combined with scholarly discussion of Coles Creek burial practices, the future research to more fully understand Coles Creek mortuary analyses presented here focus on recognizing social organization. correspondences among sex, age, and burial position. Using assemblages from three Coles Creek sites (Greenhouse, Lake George, and Mount Nebo), I find that while there is Site Descriptions significant intersite variability among Coles Creek mortuary programs, certain age groups are consistently treated The small number of Coles Creek sites that have been differently from each other and from everyone else. Thus systematically excavated limits the body of information interments were being made with deliberate care and available about mortuary practices. Moreover, al- consideration for those involved and are not nearly as though small numbers of burials have been reported haphazard and disorderly as previously thought. from numerous Coles Creek sites throughout the lower Mississippi Valley, few have provided large enough assemblages to allow for the identification of statistical Two characteristics of prehistoric societies in the patterns. The Greenhouse, Lake George, and Mount southeastern United States are commonly used to Nebo sites were chosen for this analysis principally support arguments for the presence of chiefly political based on the availability of high-quality data from a and social organization. -

University of Oklahoma

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE WISTER AREA FOURCHE MALINE: A CONTESTED LANDSCAPE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By SIMONE BACHMAI ROWE Norman, OKlahoma 2014 WISTER AREA FOURCHE MALINE: A CONTESTED LANDSCAPE A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY BY ______________________________ Dr. Lesley RanKin-Hill, Co-Chair ______________________________ Dr. Don Wyckoff, Co-Chair ______________________________ Dr. Diane Warren ______________________________ Dr. Patrick Livingood ______________________________ Dr. Barbara SafiejKo-Mroczka © Copyright by SIMONE BACHMAI ROWE 2014 All Rights Reserved. This work is dedicated to those who came before, including my mother Nguyen Thi Lac, and my Granny (Mildred Rowe Cotter) and Bob (Robert Cotter). Acknowledgements I have loved being a graduate student. It’s not an exaggeration to say that these have been the happiest years of my life, and I am incredibly grateful to everyone who has been with me on this journey. Most importantly, I would like to thank the Caddo Nation and the Wichita and Affiliated Tribes for allowing me to work with the burials from the Akers site. A great big thank you to my committee members, Drs. Lesley Rankin-Hill, Don Wyckoff, Barbara Safjieko-Mrozcka, Patrick Livingood, and Diane Warren, who have all been incredibly supportive, helpful, and kind. Thank you also to the Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum of Natural History, where most of this work was carried out. I am grateful to many of the professionals there, including Curator of Archaeology Dr. Marc Levine and Collections Manager Susie Armstrong-Fishman, as well as Curator Emeritus Don Wyckoff, and former Collection Managers Liz Leith and Dr.