As Northwest India's Stepwells Fall Into Ever Worse States of Disuse And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thesis, Dissertation

AN EXPLORATION OF SMALL TOWN SENSIBILTIES by Lucas William Winter A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture in Architecture MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, Montana April 2010 ©COPYRIGHT by Lucas William Winter 2010 All Rights Reserved ii APPROVAL of a thesis submitted by Lucas William Winter This thesis has been read by each member of the thesis committee and has been found to be satisfactory regarding content, English usage, format, citation, bibliographic style, and consistency and is ready for submission to the Division of Graduate Education. Steven Juroszek Approved for the Department of Architecture Faith Rifki Approved for the Division of Graduate Education Dr. Carl A. Fox iii STATEMENT OF PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Montana State University, I agree that the Library shall make it available to borrowers under rules of the Library. If I have indicated my intention to copyright this thesis by including a copyright notice page, copying is allowable only for scholarly purposes, consistent with “fair use” as prescribed in the U.S. Copyright Law. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this thesis in whole or in parts may be granted only by the copyright holder. Lucas William Winter April 2010 iv TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. THESIS STATEMENT AND INRO…...........................................................................1 2. HISTORY…....................................................................................................................4 3. INTERVIEW - WARREN AND ELIZABETH RONNING….....................................14 4. INTERVIEW - BOB BARTHELMESS.…………………...…....................................20 5. INTERVIEW - RUTH BROWN…………………………...…....................................27 6. INTERVIEW - VIRGINIA COFFEE …………………………...................................31 7. CRITICAL REGIONALISM AS RESPONSE TO GLOBALIZATION…………......38 8. -

Steven Holl Architects

MUMBAI CITY MUSEUM NORTH WING DESIGN COMPETITION EXHIBITION Shortlisted Teams’ Summaries Steven Holl Architects Winner ADDITION AS SUBTRACTION: Mumbai City Museum’s new North Wing addition is envisioned as a sculpted subtraction from a simple geometry formed by the site boundaries. The sculpted cuts into the white concrete structure bring diffused natural light into the upper galleries. Deeper subtractive cuts bring in exactly twenty-five lumens of natural light to each gallery. The basically orthogonal galleries are given a sense of flow and spatial overlap from the light cuts. The central cut forms a shaded monsoon water basin which runs into a central pool. In addition to evaporative cooling, the pool provides sixty per cent of the museum’s electricity through photovoltaic cells located below the water’s surface. The white concrete structure has an extension of local rough-cut Indian Agra red stone. The circulation through the galleries is one of spatial energy, while the orthogonal layout of the walls foregrounds the spectacular Mumbai City Museum collections. MUMBAI CITY MUSEUM NORTH WING DESIGN COMPETITION EXHIBITION Shortlisted Teams’ Summaries AL_A Honourable mention Using the power of absence to create connections between the old and the new, a sunken courtyard or aangan, taking inspiration from the deep and meaningful significance of the Indian stepwell, is embedded between the existing Museum building and the new North Wing. The courtyard is a metaphor for the cycle of the seasons, capturing the dramatic contrasts of the climate in the fabric of the museum. It is a metaphor for the cycle of time, where people can rethink their place in the world in a space for contemplation and a place for art and culture. -

INDIA Golden Triangle

EL SOL TRAVEL & TOURS SDN BHD 28805-T KKKP: 0194 Tel: 603 7984 4560 Fax: 603 7984 4561 [email protected] www.elsoltravel.com 6D4N Dec 15–20 INDIA Golden Triangle DELHI, AGRA & JAIPUR plus ABHANERI STEPWELL 5 UNESCO World Heritage: Red Fort, Taj Mahal, Agra Fort, Amber Fort and Jantar Mantar observatory DEC 15 TUE: Delhi arrival – Agra (D) 9.15am Malindo Air departure from KLIA2. Arrival Delhi airport 12.15pm. Transfer to Agra for dinner and check into your hotel. Overnight in Agra. OPTIONAL USD 20 /person: Enjoy live theater performance "Mohabbat the Taj", based on story of Taj Mahal; the love story between Emperor Shahjahan & wife Mumtaj Mahal. DEC 16 WED: Agra – Abhaneri - Jaipur (B/L/D) Visit UNESCO World Heritage Taj Mahal, amongst the most photographed monument in the world. This brilliant white marble building is a mausoleum built by Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan in memory of his 3rd wife, Mumtaz Mahal. Taj Mahal is regarded by many as the finest example of Mughal architecture, a style that combines elements from Islamic, Persian, Ottoman Turkish and Indian architectural styles. Then visit UNESCO World Heritage Agra Fort. Ever since Babur defeated and killed Ibrahim Lodi at Panipat in 1526, Agra became an important center of Mughal Empire. Akbar chose this city on the bank of River Yamuna as his capital and proceeded to build a strong citadel for the purpose. It is said that he destroyed the damaged old fort of Agra for the purpose and raised this grand group of monuments instead in red sandstone. Transfer to Abhaneri to visit the amazing stepwell (or 'baoris') and Harshat Mata Temple. -

DSS Senior Serv-Final-Ocr.Pdf

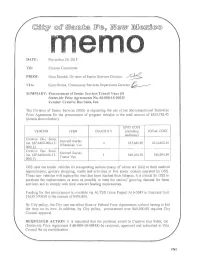

DATE: November 29, 2018 TO: Finance Committee FROM: Gino Rinaldi, Di vision of Senior Services Director ~ VIA: Kyra Ochoa, Community Services Department Director tf::__---- SUI\11\1ARY: Procurement of Senior Services Transit Vans (5) Statewide Price Agreements No. 60-000-15-00015 Vendor: Creative Bus Sales, Inc. The Division of Senior Services (DSS) is requesting the use of the abovementioned Statewide Price Agreement for the procurement of program vehicles in the total amount of $263,758.45 (details shown below). UNIT COST VENDOR ITEM QUANTITY (including TOTAL COST additions) Creative Bus Sales, Starcrafl Starlitc Inc. (SPA#60-000-15- 4 S53,665.89 S214,663.56 Wheelchair \Inn 00015) Creative Bus Sales, Starcraft Starlitc Inc. (SP.'\#60-000-15 - I S49,094.89 S49,094.89 Transit Van 00015) DSS uses the transit \'chicles for transporting seniors (many of whom are frail) to their medical appointments, grocery shopping, meals and activities at five senior centers operated by DSS. These new vehicles will replace the ones that have reached their lifespan. lt is critical for DSS to purchase the replacements as soon as possible to meet the seniors' growing demand for these services, and to comply with their contract fu nding requirements. Funt.ling for this procurement is available via AL TSD Grant Project A 16-5087 in Business Unit 22639.570950 in the amount ofS459.800. By City policy, the City c.:an use either State or Federal Price Agreements without having to bid the item on its own. In addition, by City policy, procurement over $60,000.00 requires City Council approval. -

India's Subterranean Stepwells: Photographs by Victoria Lautman

India’s Subterranean Stepwells: Photographs by Victoria Lautman May 5–October 20, 2019 Contact: Erin Connors, 310-825-4288, [email protected] Los Angeles—The Fowler Museum at UCLA presents India’s Subterranean Stepwells: Photographs by Victoria Lautman, 48 photographs of monumental manmade water storage systems called stepwells, also known as baolis, vavs and kunds in various parts of the country. These magnificent inverted constructions extend down to the water table, ranging from three to 13 stories deep. Villagers, religious pilgrims, and transient traders once descended into the stepwells to find clean water and a cool, quiet reprieve from the heat above. Journalist Victoria Lautman first encountered these subterranean architectural marvels 30 years ago, and has since documented more than 200 sites—some preserved as heritage sites and some restored as functioning community wells and active shrines, while others remain forgotten and derelict. The exhibition will be on view at the Fowler through October 20, 2019. “Palaces, forts, temples, and tombs are on every tourist itinerary and in every guidebook to India,” Lautman said. “The country’s magnificent subterranean stepwells, however, remain largely unknown within and outside the country.” Stepwells were engineered and constructed from around 600 CE. This exhibition focuses on documentation of 16 sites, built between the 9th and 18th centuries. As many as 3,000 stepwells once existed across Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh, where seasonal monsoonal rains in the parched landscape of northwest India necessitated a water storage system. Often commissioned by wealthy female patrons, stepwells were sites of communal congregation and conviviality open to all, providing water for consumption, cleansing, irrigation, and ritual use. -

Transit Security Procedures Guide

FTA-MA-90-7001-94-2 DOT-VNTSC-FTA-94-8 Pw Transit Security U. S. Department of Transportation Procedures Guide Federal Transit Administration U.S. Department of Transportation Research and Special Programs Administration John A. Volpe National Transportation Systems Center December 1994 Cambridge MA 02142 Final Report NOTICE This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. NOTICE The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trade or manufacturers’ names appear herein solely because they are considered essential to the objective of this report. NOTICE This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. NOTICE The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trade or manufacturers’ names appear herein solely because they are considered essential to the objective of this report. HETRIC/ENGLISH CONVERSIOY FACTORS ENGLISH TO RETRIC KETRIC TO ENGLISH LENGTH (APPROXIMATE) LENGTH (APPROXIIIATE) 1 inch (in) = 2.5 centimeters (a) 1 milliwter (set) = 0.W inch (in) 1 foot (ft) = 30 centimeters (an) 1 centimeter (cm) = 0.4 inch (in) 1 yard (yd) = 0.9 meter (m) 1 meter Cm) = 3.3 feet (ft) 1 mile (mi) = 1.6 kitaneters (km) 1 swster (m) = 1.1 yards (yd) 1 kilcanster (km) = 0.6 mile -

13:34:32 Paid Invoice Listing Id: Ap450000.Wow

DATE: 06/05/2017 CITY OF DEKALB PAGE: 1 TIME: 13:34:32 PAID INVOICE LISTING ID: AP450000.WOW FROM 05/01/2017 TO 05/31/2017 VENDOR # INVOICE # INV. DATE CHECK # CHK DATE CHECK AMT INVOICE AMT/ ITEM DESCRIPTION ACCOUNT NUMBER P.O. NUM ITEM AMT ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ACCTAN ACCURATE TANK TECHNOLOGIES 26595 04/18/17 52109 05/23/17 545.00 545.00 01 FUEL TANK INSPECTIONS 0130332008245 00000000 545.00 VENDOR TOTAL: 545.00 AIRCYC AIR CYCLE CORPORATION 0147608-IN 04/06/17 52110 05/23/17 4,960.00 4,960.00 01 BULB EATER, CHUTE, FILTER 0700003008354 00000000 4,960.00 VENDOR TOTAL: 4,960.00 AIRGAS AIRGAS, INC. 9062965692 04/28/17 52111 05/23/17 650.55 91.05 01 MEDICAL O2 0125272008241 00000000 91.05 9943460718 03/31/17 51954 05/09/17 134.29 134.29 01 CYLINDER RENTAL/REFILL 0130332008226 00000000 67.15 02 CYLINDER RENTAL/REFILL 6000002008226 00000000 67.14 9944247823 04/30/17 52111 05/23/17 650.55 559.50 01 MEDICAL O2 0125272008241 00000000 559.50 VENDOR TOTAL: 784.84 ALECHE ALEXANDER CHEMICAL CORP SLS 10057559 03/29/17 51955 05/09/17 1,224.00 1,224.00 01 CHLORINE/FLUORIDE -POTABLE WTR 6000002008250 00170029 1,224.00 VENDOR TOTAL: 1,224.00 ALEFIR ALEXIS FIRE EQUIPMENT CO 0058740-IN 03/31/17 51956 05/09/17 44.91 44.91 01 STEPWELL LAMP 0125272008226 00000000 44.91 0058909-IN 04/18/17 52112 05/23/17 360.92 227.26 01 SOLENOID VALVE 0125272008226 00000000 227.26 0058922-IN 04/18/17 52112 05/23/17 360.92 133.66 01 DRAIN VALVE 0125272008226 00000000 133.66 VENDOR TOTAL: 405.83 ALUAWA LARSEN CREATIVE INC 1213 03/08/17 51957 05/09/17 72.75 72.75 DATE: 06/05/2017 CITY OF DEKALB PAGE: 2 TIME: 13:34:32 PAID INVOICE LISTING ID: AP450000.WOW FROM 05/01/2017 TO 05/31/2017 VENDOR # INVOICE # INV. -

Bawdi: the Eloquent Example of Hydrolic Engineering and Ornamental Architecture

[Pandey *, Vol.4 (Iss.1): January, 2016] ISSN- 2350-0530(O) ISSN- 2394-3629(P) Impact Factor: 2.035 (I2OR) DOI: 10.29121/granthaalayah.v4.i1.2016.2867 Arts BAWDI: THE ELOQUENT EXAMPLE OF HYDROLIC ENGINEERING AND ORNAMENTAL ARCHITECTURE Dr. Anjali Pandey *1 *1 Assistant Professor (Drawing & Painting), Govt. M.L.B. Girls P.G. College, Bhopal, INDIA ABSTRACT “The secular Indian architecture includes town planning, palaces, general houses and forts of various categories. There was a constant growth in forms of this architecture from the period of harappan culture up to the Vijaynagar epoch. The towns were protected by walls (prakara) and the moats parikha. Each town provided places of general public utility, such as temples, stupas, schools, hospitals, markets, gardens and ponds”.1 Keywords: Hydrolic Engeering, Ornamental Architecture, Bawdi, Indian architecture. Cite This Article: Dr. Anjali Pandey, “BAWDI: THE ELOQUENT EXAMPLE OF HYDROLIC ENGINEERING AND ORNAMENTAL ARCHITECTURE” International Journal of Research – Granthaalayah, Vol. 4, No. 1 (2016): 217-222. 1. INTRODUCTION Bawdi are usually known as Stepwell, Stairwells, Baori, Baoli or Vav. It is the manmade pond with significant ornamental architectural structure for water conservation of ancient India. These wells are commonly found at western region of India for irrigation and storage of water mainly to cope with seasonal fluctuations.2 Water Exploitation and management have been of great concern for a developing and developed urban civilization that the Harappans created. The most ancient example of water management is found from proto-historic period, primarily from harappan sites. The hydraulic structures from Mohenjo-Daro (undivided India) are eloquent examples which attain the phenomenon excellence. -

Chand Baori: an Engineering Marvel

Chand Baori: An Engineering Marvel In 1864, the French adventurer Louis Rousselet, while in India, described “[a] vast sheet of water, covered with lotuses in flower, amid which thousands of aquatic birds are sporting at the shores of which bathers washed, surrounded by jungle greenery.” This was not about the shores of some picturesque lake or even one of the famous River Ghats common in India, but an ancient stepwell. When the form, transcends the mundane utilitarian considerations behind it, the result is often recognised as a work of art. This stepwell known as Chand Baori is about a hundred kilometres east of Jaipur in the Dausa district of eastern Rajasthan at a place called Abaneri, a shortened version of its original name of Abha Nagari, or the City of Lights. Though there are no records of the commencement of the construction of the baori, the architectural style and its embellishments place its original structures in the second half of the eighth century AD. These original structures remain a legacy of the technical finesse achieved, more than a thousand years back. Unlike most other step wells Chand Baori was refurbished often, including the addition of an enclosure, verandahs wall and pavilions in the upper layers, incorporating arches, during the Mughal era in the eighteenth century. Built in a square format with each of the sides thirty- five meters in length and reaching down to a depth of nineteen and a half meters, it is one of the oldest, largest and the deepest step wells in India. This engineering marvel, built like an inverted pyramid, was conceived and executed with remarkable mathematical precision. -

Annual Report 2009-2010

Annual Report 2009-2010 CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES GOVERNMENT OF INDIA FARIDABAD CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD Ministry of Water Resources Govt. of India ANNUAL REPORT 2009-10 FARIDABAD ANNUAL REPORT 2009 - 2010 CONTENTS Sl. CHAPTERS Page No. No. Executive Summary I - VI 1. Introduction 1 - 4 2. Ground Water Management Studies 5 - 51 3. Ground Water Exploration 52 - 78 4. Development and Testing of Exploratory Wells 79 5. Taking Over of Wells by States 80 - 81 6. Water Supply Investigations 82 - 83 7. Hydrological and Hydrometereological Studies 84 - 92 8. Ground Water Level Scenario 93 - 99 (Monitoring of Ground Water Observation Wells) 9. Geophysical Studies 100- 122 10. Hydrochemical Studies 123 - 132 11. High Yielding Wells Drilled 133 - 136 12. Hydrology Project 137 13. Studies on Artificial Recharge of Ground Water 138 - 140 14. Mathematical Modeling Studies 141 - 151 15. Central Ground Water Authority 152 16. Ground Water Studies in Drought Prone Areas 153 - 154 17. Ground Water Studies in Tribal Areas 155 18. Estimation of Ground Water Resources 156 - 158 based on GEC-1997 Methodology 19. Technical Examination of Major/Medium Irrigation Schemes 159 Sl. CHAPTERS Page No. No. 20. Remote Sensing Studies 160 - 161 21. Human Resource Development 162 - 163 22. Special Studies 164 - 170 23. Technical Documentation and Publication 171 - 173 24. Visits by secretary, Chairman CGWB , delegations and important meetings 174 - 179 25. Construction/Acquisition of Office Buildings 180 26. Dissemination and Sharing of technical know-how (Participation in Seminars, 181 - 198 Symposia and Workshops) 27. Research and Development Studies/Schemes 199 28. -

Final Copy 2019 05 07 Chen

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from Explore Bristol Research, http://research-information.bristol.ac.uk Author: Chen, Chien-Nien Title: Harmonious Environmental Management of Cultural Heritage and Nature General rights Access to the thesis is subject to the Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International Public License. A copy of this may be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode This license sets out your rights and the restrictions that apply to your access to the thesis so it is important you read this before proceeding. Take down policy Some pages of this thesis may have been removed for copyright restrictions prior to having it been deposited in Explore Bristol Research. However, if you have discovered material within the thesis that you consider to be unlawful e.g. breaches of copyright (either yours or that of a third party) or any other law, including but not limited to those relating to patent, trademark, confidentiality, data protection, obscenity, defamation, libel, then please contact [email protected] and include the following information in your message: •Your contact details •Bibliographic details for the item, including a URL •An outline nature of the complaint Your claim will be investigated and, where appropriate, the item in question will be removed from public view as soon as possible. Harmonious Environmental Management of Cultural Heritage and Nature By Chien-Nien Chen (Otto Chen) BSc, MSc A Dissertation submitted to the University of Bristol in accordance with the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Engineering Department of Civil Engineering Mar 2019 Approximately 74000 words One night a man had a dream. -

Approach Paper Rajasthan State

Approach Paper Rajasthan State 2014-2015 Mr. Dinesh Songara, Dr. Akanksha Goyal, Dr. Pankaj Suthar Guidance: Dr. Nirupam Bajpai (Project Director), Dr. Esha Sheth Model Districts Health Project Columbia Global Centers | South Asia (Mumbai) Earth Institute, Columbia University Express Towers 11th Floor, Nariman Point, Mumbai 400021 globalcenters.columbia.edu/Mumbai Table of Contents List of Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................... 2 Summary of Recommendations .............................................................................................................. 4 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 8 2. Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) - Reforms and Career Path .......................................... 11 3. Strengthening of FRUs .................................................................................................................. 19 4. High risk Pregnancy- identification and tracking .......................................................................... 27 5. Quality Training to build the Capacity of Service Providers.......................................................... 33 6. Sub Center strengthening ............................................................................................................. 34 7. Data Driven Planning in Health ....................................................................................................