Full Text (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Afrofuturism: the World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture

AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISM Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 1 5/22/13 3:53 PM Copyright © 2013 by Ytasha L. Womack All rights reserved First edition Published by Lawrence Hill Books, an imprint of Chicago Review Press, Incorporated 814 North Franklin Street Chicago, Illinois 60610 ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Womack, Ytasha. Afrofuturism : the world of black sci-fi and fantasy culture / Ytasha L. Womack. — First edition. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 (trade paper) 1. Science fiction—Social aspects. 2. African Americans—Race identity. 3. Science fiction films—Influence. 4. Futurologists. 5. African diaspora— Social conditions. I. Title. PN3433.5.W66 2013 809.3’8762093529—dc23 2013025755 Cover art and design: “Ioe Ostara” by John Jennings Cover layout: Jonathan Hahn Interior design: PerfecType, Nashville, TN Interior art: John Jennings and James Marshall (p. 187) Printed in the United States of America 5 4 3 2 1 I dedicate this book to Dr. Johnnie Colemon, the first Afrofuturist to inspire my journey. I dedicate this book to the legions of thinkers and futurists who envision a loving world. CONTENTS Acknowledgments .................................................................. ix Introduction ............................................................................ 1 1 Evolution of a Space Cadet ................................................ 3 2 A Human Fairy Tale Named Black .................................. -

W41 PPB-Web.Pdf

The thrilling adventures of... 41 Pocket Program Book May 26-29, 2017 Concourse Hotel Madison Wisconsin #WC41 facebook.com/wisconwiscon.net @wisconsf3 Name/Room No: If you find a named pocket program book, please return it to the registration desk! New! Schedule & Hours Pamphlet—a smaller, condensed version of this Pocket Program Book. Large Print copies of this book are available at the Registration Desk. TheWisSched app is available on Android and iOS. What works for you? What doesn't? Take the post-con survey at wiscon.net/survey to let us know! Contents EVENTS Welcome to WisCon 41! ...........................................1 Art Show/Tiptree Auction Display .........................4 Tiptree Auction ..........................................................6 Dessert Salon ..............................................................7 SPACES Is This Your First WisCon?.......................................8 Workshop Sessions ....................................................8 Childcare .................................................................. 10 Children's and Teens' Programming ..................... 11 Children's Schedule ................................................ 11 Teens' Schedule ....................................................... 12 INFO Con Suite ................................................................. 12 Dealers’ Room .......................................................... 14 Gaming ..................................................................... 15 Quiet Rooms .......................................................... -

229 INDEX © in This Web Service Cambridge

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-05246-8 - The Cambridge Companion to: American Science Fiction Edited by Eric Carl Link and Gerry Canavan Index More information INDEX Aarseth, Espen, 139 agency panic, 49 Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (fi lm, Agents of SHIELD (television, 2013–), 55 1948), 113 Alas, Babylon (Frank, 1959), 184 Abbott, Carl, 173 Aldiss, Brian, 32 Abrams, J.J., 48 , 119 Alexie, Sherman, 55 Abyss, The (fi lm, Cameron 1989), 113 Alias (television, 2001–06, 48 Acker, Kathy, 103 Alien (fi lm, Scott 1979), 116 , 175 , 198 Ackerman, Forrest J., 21 alien encounters Adam Strange (comic book), 131 abduction by aliens, 36 Adams, Neal, 132 , 133 Afrofuturism and, 60 Adventures of Superman, The (radio alien abduction narratives, 184 broadcast, 1946), 130 alien invasion narratives, 45–50 , 115 , 184 African American science fi ction. assimilation of human bodies, 115 , 184 See also Afrofuturism ; race assimilation/estrangement dialectic African American utopianism, 59 , 88–90 and, 176 black agency in Hollywood SF, 116 global consciousness and, 1 black genius fi gure in, 59 , 60 , 62 , 64 , indigenous futurism and, 177 65 , 67 internal “Aliens R US” motif, 119 blackness as allegorical SF subtext, 120 natural disasters and, 47 blaxploitation fi lms, 117 post-9/11 reformulation of, 45 1970s revolutionary themes, 118 reverse colonization narratives, 45 , 174 nineteenth century SF and, 60 in space operas, 23 sexuality and, 60 Superman as alien, 128 , 129 Afrofuturism. See also African American sympathetic treatment of aliens, 38 , 39 , science fi ction ; race 50 , 60 overview, 58 War of the Worlds and, 1 , 3 , 143 , 172 , 174 African American utopianism, 59 , 88–90 wars with alien races, 3 , 7 , 23 , 39 , 40 Afrodiasporic magic in, 65 Alien Nation (fi lm, Baker 1988), 119 black racial superiority in, 61 Alien Nation (television, 1989–1990), 120 future race war theme, 62 , 64 , 89 , 95n17 Alien Trespass (fi lm, 2009), 46 near-future focus in, 61 Alien vs. -

SLF Portolan Project Interview with Nalo Hopkinson, Andrea Hairston, and Sheree Renée Thomas Los Angeles, California, 2019

SLF Portolan Project Interview with Nalo Hopkinson, Andrea Hairston, and Sheree Renée Thomas Los Angeles, California, 2019 Mary Anne Mohanraj: Hi everybody, this is Mary Anne Mohanraj, and I'm here at the World Fantasy Convention 2019 in Los Angeles. I'm here with Nalo Hopkinson, Andrea Hairston, and Sheree Renée Thomas, really delighted to be interviewing them for the SLF. So, I thought we would start with how I first got to know all of you and your work. I think the first one was Nalo Hopkinson. I met Nalo at WisCon, it would have been, I want to say around 1997-98, when WisCon was making a real effort to do outreach to people of color, and they had actually invited me to come, and I was a starving grad student at the time, and said I couldn't possibly fly from California all the way to Madison. And they had covered my expenses to attend the convention. And I got there, and there were five people of color, at the seven – Andrea Hairston: That was a good year. [laughter] Mary Anne Mohanraj: Yeah, at the 700-something person convention. So they had an issue, which they were trying to address. And Nalo was one of them. Does that match up with your memory? And, I don't know, was that your first WisCon as well, or? Nalo Hopkinson: My first WisCon was right after Clarion, and I did Clarion in ‘95, so it was probably a few years before. Mary Anne Mohanraj: A little before, then. Nalo Hopkinson: I think I knew who you were before then. -

Black Feminism in African American Science Fiction 2015

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Bc. Lenka Drešerová Midnight Queens Dreaming: Black Feminism in African American Science Fiction Master’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: doc. PhDr. Tomáš Pospíšil, Ph. D. 2015 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Author’s signature 2 Acknowledgements: I would like to thank doc. PhDr. Tomáš Pospíšil, Ph.D. for his kind help and supervision of my diploma thesis, my sisters for being my role models and my partner for his support. 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction.................................................................................................................5 I.1. African American Science Fiction................................................................10 I.2. Theoretical Background: Afrofuturism and Black Feminism.......................15 I.3. Octavia E. Butler and Nalo Hopkinson.........................................................20 II. Race: Negotiation, Implication, Exhaustion.............................................................27 II.1. Ancestry: Revisiting the Past........................................................................28 II.2. Race and Societies: Envisioning Safe Places................................................36 II.3. The New Mestiza in African American Science Fiction..............................45 III. Gender: Black Girls Are the Future..........................................................................49 -

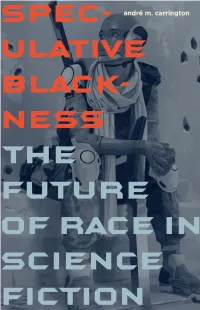

Speculative Blackness This Page Intentionally Left Blank Speculative Blackness

Speculative BlackneSS This page intentionally left blank SPECULATIVE BLACKNESS The Future of Race in Science Fiction andré m. carrington University of Minnesota Press Minneapolis London A version of chapter 4 appeared as “Drawn into Dialogue: Comic Book Culture and the Scene of Controversy in Milestone Media’s Icon,” in The Blacker the Ink, ed. Frances Gateward and John Jennings (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2015). Por- tions of chapter 6 appeared as “Dreaming in Colour: Fan Fiction as Critical Reception,” in Race/Gender/Class/Media, 3d ed., ed. Rebecca Ann Lind (Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson, 2013), 95–101; copyright 2013, printed and electronically reproduced by per- mission of Pearson Education, Inc. Copyright 2016 by the Regents of the University of Minnesota All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy- ing, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Published by the University of Minnesota Press 111 Third Avenue South, Suite 290 Minneapolis, MN 55401- 2520 http://www.upress.umn.edu Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Carrington, André M. Speculative blackness: the future of race in science fiction / andré m. carrington. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8166-7895-2 (hc) ISBN 978-0-8166-7896-9 (pb) 1. American fiction—African American authors—History and criticism. 2. Science fiction, American—History and criticism. 3. Race in literature. 4. African Americans in mass media. 5. African Americans in popular culture I. -

Afro-Future Females

Afro-Future Females Barr_final.indb 1 4/15/2008 2:52:25 AM Barr_final.indb 2 4/15/2008 2:52:25 AM Afro-Future Females Black Writers Chart Science Fiction’s Newest New-Wave Trajectory Edited by MARLEEN S. BARR T H E O H I O S TAT E U N I V E R S I T Y P R E ss / Columbus Barr_final.indb 3 4/15/2008 2:52:25 AM Copyright © 2008 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Afro-future females : black writers chart science fiction’s newest new-wave trajectory / edited by Marleen S. Barr. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN-13: 978–0–8142–1078–9 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Science fiction, American. 2. Science fiction, American—History and criticism. 3. American fiction—African American authors—History and criticism. 4. American fic- tion—Women authors—History and criticism. 5. Women and literature—United States— History—20th century. 6. Women and literature—United States—History—21st century. I. Barr, Marleen S. PS648.S3A69 2008 813.’0876209928708996073—dc22 2007050083 This book is available in the following editions: Cloth (ISBN 978–0–8142–1078–9) CD-ROM (ISBN 978–0–8142–9156–6) Cover design by Janna Thompson Chordas. Text design by Jennifer Shoffey Forsythe. Type set in Adobe Minion. Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48–1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Barr_final.indb 4 4/15/2008 2:52:25 AM Contents PRefAce “All At One Point” Conveys the Point, Period: Or, Black Science Fiction Is Bursting Out All Over ix IntRODUctiOns: “DARK MAtteR” MAtteRS l Imaginative Encounters Hortense J. -

Science Fiction, Feminism, African American Voices, and Octavia E

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette English Faculty Research and Publications English, Department of 3-1-2014 Missing Octavia: A Review of Strange Matings: Science Fiction, Feminism, African American Voices, and Octavia E. Butler Gerry Canavan Marquette University, [email protected] Published version. Science Fiction Studies, Vol. 41, No. 1 (March 2014): 223-225. DOI. © 2014 DePauw University. Used with permission. BOOKS IN REVIEW 223 It is, as they cite Hilary Rose, a “dream laboratory” for feminist science studies. The authors point out how Haraway sees Octavia Butler’s work as disruptive of the totalizing tendencies and boundary policing prevalent in sociobiology. Interestingly, they also see in Haraway’s work the evolution of a set of reading protocols that they compare to Samuel R. Delany’s. Finally, they compare her use of story in understanding nature/culture to Ursula K. Le Guin’s “The Carrier-Bag Theory of Fiction” (1986), nicely setting up the final chapter of the book. “Sowing Worlds: A Seed Bag for Terraforming with Earth Others” is Donna Haraway’s generous contribution to the volume, a tour de force in which she weaves together acacia seeds and ants with Le Guin’s story “The Author of the Acacia Seeds and Other Extracts from the Journal of the Association of Therolinguistics” (1987), essentially rewriting the story to demonstrate symbiosis between nature and culture, story and science, so that, as she concludes, “sympoesis displaces autopoesis and all other self-forming and self-sustaining system fantasies. Sympoesis is a carrier bag for ongoingness, a yoke for becoming with, for staying with the trouble of inheriting the damages and achievements of colonial and postcolonial naturalcultural histories in telling the tale of still possible recuperation” (145- 46). -

Aqueduct Press 2020

AQUEDUCT PRESS 2020 WORK TO STRETCH THE IMAGINATION AND STIMULATE THOUGHT 1 New Releases Unbecoming The WisCon Chronicles, Vol. 12 by Lesley Wheeler’ Boundaries & Bridges (ISBN: 978-1-61976-167-4) edited by Isabel Schechter & Michi Trota What if women gained uncanny power at middle age? (ISBN: 978-1-61976-191-9) In Unbecoming, Cyn’s family is shattering and she is at war with her own body. Then, when her best friend andThis Tiptree/Otherwise collection includes Award-winningessays from first-time authors and glamorous stranger takes her place—Fee Ellis, a Welsh WisCon attendees and former Guests of Honor, fans flies off on a mysterious faculty exchange program, a poet who makes it all look easy. But it may be costly to less well-off, abled and disabled, white and POC, young welcome this charismatic outsider to their little college andeditors, old, cisparents het and and LGBTQ+ child-free, attendees, English affluent speakers and and town. Cyn’s best friend, meanwhile, communicates only Spanish speakers, and hopefully more than just these in ominous fragments. categories can capture. “A middle-aged college professor taps into her magical ability in the midst of personal and professional and thoughts about WisCon. Structural changes in the conventionTheir essays that cover break a wide down range barriers of experiences to attendance with (The Receptionist and Other Tales).… Wheeler’s prose and participation are important, and some of the ischaos gorgeous in this and excellent her characters feminist arefantasy marvelously from Wheeler essays recount the process and struggles of creating detailed.… Readers will be taken with this powerful space and programming for POC attendees, access for and deeply satisfying tale.” (Starred Review) disabled attendees, and affordability for all attendees. -

A Study of African-American Participation in Science Fiction Conventions

DESEGREGATING THE FUTURE: A STUDY OF AFRICAN-AMERICAN PARTICIPATION IN SCIENCE FICTION CONVENTIONS Rebecca Lynn Testerman A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of The requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2012 Committee: Esther A. Clinton, Advisor Ellen E. Berry ii ABSTRACT Esther A. Clinton, Advisor The purpose of this study is to investigate and analyze African-American participation in science fiction fan culture at science fiction conventions. My inquiry will include four main sections involving how and why African-Americans seem to be underrepresented at science fiction conventions in comparison to their proportion of the general population. These include a brief history of science fiction conventions, an exploration of the possible reasons for African- Americans who read science fiction literature or watch the television shows and movies would chose not to participate in science fiction conventions, some examples of positive portrayals of black characters in both science fiction literature and visual media, and the personal observations of my research subjects on their experiences regarding attending science fiction conventions. My research methodology included personal interviews with several African-American science fiction fans and authors, an interview with a white science fiction fan who is very familiar with the history of fan culture. I also draw upon scholarship in the science fiction studies, cultural anthropology and critical race theory. iii This work is dedicated to: my late Mother, Eldora Read Testerman, For getting me my first library card when I was six years old, For reading to me, and for encouraging me to do well in school; And my Father, Raymond Lee Testerman, who let me watch Star Trek, Lost in Space and The Twilight Zone. -

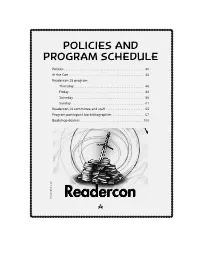

Readercon 28 Program Guide

POLICIES AND PROGRAM SCHEDULE Policies � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 40 At the Con � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 44 Readercon 28 program Thursday � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 46 Friday � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 48 Saturday � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 56 Sunday � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 61 Readercon 28 committee and staff � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 65 Program participant bio-bibliographies � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 67 Bookshop dealers � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 100 Art © Andrew King 40 POLICIES Readercon needs volunteer help this weekend 8 hours earns a free membership for Readercon 29 in 2018! You can even earn credit for watching programming� Stop by the Info Desk to find out how. POLICIES Cell phones must be set to silent or vibrate mode in panel discussion rooms. No smoking in programming areas or the Bookshop, by state law and hotel policy� Only service animals in convention areas. No weapons in convention areas. Young children who are always with an adult are admitted free; others need a membership. See “Children Attending Readercon” on page 43 for more information� Any disruptive or inappropriate behavior may lead to being asked -

Midfanzine #4

TTTAAABBBLLLEEE OOOFFF CCCOOONNNTTTEEENNNTTTSSS Editorial Comments 1 By Anne KG Murphy Tips on Dating Your Hotel 2 By Jer Lance Hotel Liaising for your ConCom: Information Flow 4 By Anne KG Murphy Top Ten Things Your Hotel Can Do For You 7 By Anne KG Murphy Midfan Access #1 Why We Do It & Signage 8 By Jesse the K Welcoming a Diverse Community to Your Con 11 By Anne KG Murphy U-Con’s Smooth Moves 12 By Laura Hamel How to Run a Bone Marrow Registry Drive at Your Con 15 By Val Grimm Midwest Convention Calendar 17 Letters of Comment Request 18 AAARRRTTT CCCRRREEEDDDIIITTTSSS Kurt Erichsen Cover Brad Foster 2 Frank Wu 9 Photos by Anne Murphy & Brian Gray 13, 14 MidFanzine 4: Next Steps Fall, 2009 Available for $3 or the Usual to [email protected]. Anne KG Murphy, 120 S Walnut St, Yellow Springs, OH, 45387. Articles and art submissions welcome. MidFanzine is produced by Midwest Fannish Conventions (Midfan), which is a loosely associated group of like-minded Midwest smofs who want to encourage knowledge-sharing about convention running in the Midwest. It used to be a legal entity, has run a few conventions, and may do both of those things again. All rights remain with contributors. Many thanks to Kim Kofmel and Gary Farber for proofing this issue. Midfan http://www.midfan.org/ [email protected] On Facebook at http://www.facebook.com/group.php?gid=151273580660 On Livejournal at http://community.livejournal.com/midfan/ Discussion List Midfan-talk Yahoo Group, http://groups.yahoo.com/group/midfan-talk/ to sign up, email [email protected] MidFanzine 4: Next Steps 1 Editorial Comments 2005-2008 were years where a number of key Midfan executive members experienced a lot of Life (with a capital L).