The Effect of Salinity on Eastern Oyster Reproduction in the Hudson River Estuary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coastal Assessment Form Addendum

X NY Department of State, U.S. Office of Ocean & Coastal Resource Management The LWRP Update includes projects to improve water quality in Croton Bay. X X The LWRP Update proposes improvements to several Village parks and a Village-wide parks maintenance and improvement plan. Note: This section is designed for site-specific actions rather than area-wide or generic proposals. The answers to the questions reflect the fact the LWRP Update would apply to all actions wtihin the Village's coastal area, and that the Update proposes several implementation projects. These projects, if undertaken, would be subject to individual consistency review. X X Croton‐on‐Hudson Local Waterfront Revitalization Program Update VILLAGE OF CROTON‐ON‐HUDSON, NEW YORK COASTAL ASSESSMENT FORM ADDENDUM Lead Agency Village of Croton‐on‐Hudson Board of Trustees Stanley H. Kellerhouse Municipal Building 1 Van Wyck Street Croton‐on‐Hudson, NY 10520 Contact: Leo A. W. Wiegman, Mayor (914)‐271‐4848 Prepared by BFJ Planning 115 Fifth Avenue New York, NY 10003 Contact: Susan Favate, AICP, Principal (212) 353‐7458 Croton-on-Hudson LWRP Update CAF July 31, 2015 Croton-on-Hudson LWRP Update CAF July 31, 2015 1.0 LOCATION AND DESCRIPTION OF PROPOSED ACTION Pursuant to the New York State Environmental Quality Review Act (SEQR), the proposed action discussed in this Full Environmental Assessment Form (EAF) is the adoption of an update to the 1992 Local Waterfront Revitalization Program (LWRP) of the Village of Croton‐on‐Hudson. In considering adoption of the LWRP Update, the Village of Croton‐on‐Hudson Board of Trustees (BOT) are proposing to modify certain existing policies to reflect changed conditions and priorities since the 1992 LWRP, and to propose specific projects to implement those policies. -

This Article Was Originally Published in a Journal Published by Elsevier

This article was originally published in a journal published by Elsevier, and the attached copy is provided by Elsevier for the author’s benefit and for the benefit of the author’s institution, for non-commercial research and educational use including without limitation use in instruction at your institution, sending it to specific colleagues that you know, and providing a copy to your institution’s administrator. All other uses, reproduction and distribution, including without limitation commercial reprints, selling or licensing copies or access, or posting on open internet sites, your personal or institution’s website or repository, are prohibited. For exceptions, permission may be sought for such use through Elsevier’s permissions site at: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/permissionusematerial Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 71 (2007) 259e277 www.elsevier.com/locate/ecss Regional patterns and local variations of sediment distribution in the Hudson River Estuary F.O. Nitsche a,*, W.B.F. Ryan a, S.M. Carbotte a, R.E. Bell a, A. Slagle a, C. Bertinado a, R. Flood c, T. Kenna a, C. McHugh a,b a Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia Univeristy, Palisades, NY 10964, USA b Queens College, City University New York, Flushing, NY, USA c Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, USA Received 3 November 2005; accepted 27 July 2006 Available online 2 October 2006 Abstract The Hudson River Benthic Mapping Project, funded by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, resulted in a com- prehensive data set consisting of high-resolution multibeam bathymetry, sidescan sonar, and sub-bottom data, as well as over 400 sediment cores and 600 grab samples. -

Volume 26 , Number 2

The hudson RIVeR Valley ReVIew A Journal of Regional Studies HRVR26_2.indd 1 5/4/10 10:45 AM Publisher Thomas s. wermuth, Vice President for academic affairs, Marist College Editors Christopher Pryslopski, Program director, hudson River Valley Institute, Marist College Reed sparling, writer, scenic hudson Editorial Board Art Director Myra young armstead, Professor of history, Richard deon Bard College Business Manager Col. lance Betros, Professor and head, andrew Villani department of history, u.s. Military academy at west Point The Hudson River Valley Review (Issn 1546-3486) is published twice Kim Bridgford, Professor of english, a year by the hudson River Valley Fairfield university Institute at Marist College. Michael Groth, Professor of history, wells College James M. Johnson, Executive Director susan Ingalls lewis, assistant Professor of history, state university of new york at new Paltz Research Assistants sarah olson, superintendent, Roosevelt- Gail Goldsmith Vanderbilt national historic sites elizabeth Vickind Roger Panetta, Professor of history, Hudson River Valley Institute Fordham university Advisory Board h. daniel Peck, Professor of english, Todd Brinckerhoff, Chair Vassar College Peter Bienstock, Vice Chair Robyn l. Rosen, Professor of history, dr. Frank Bumpus Marist College Frank J. doherty david schuyler, Professor of american studies, shirley handel Franklin & Marshall College Marjorie hart Maureen Kangas Thomas s. wermuth, Vice President of academic Barnabas Mchenry affairs, Marist College, Chair alex Reese david woolner, -

New York City, the Lower Hudson River, and Jamaica Bay

3.4 New York City, the Lower Hudson River, and Jamaica Bay Author: Elizabeth M. Strange, Stratus Consulting Inc. Species and habitats in the region encompassing such as beach nourishment, dune construction, New York City, the lower Hudson River, the and vegetation wherever possible. Planners East River, and Jamaica Bay are potentially at expect that the only sizeable areas in the New risk because of sea level rise. Although the York City metropolitan area that are unlikely to region is one of the most heavily urbanized areas be protected are portions of the three Special along the U.S. Atlantic Coast, there are Natural Waterfront Areas (SNWAs) designated nonetheless regionally significant habitats for by the city: Northwest Staten Island/Harbor fish, shellfish, and birds in the area, and a great Heron SNWA; East River–Long Island Sound deal is known about the ecology and habitat SNWA; and Jamaica Bay SNWA. needs of these species. TIDAL WETLANDS Based on existing literature and the knowledge of local scientists, this brief literature review Staten Island. Hoffman Island and Swinburne discusses those species that could be at risk Island are National Park Service properties lying because of further habitat loss resulting from sea off the southeast shore of Staten Island; the level rise and shoreline protection (see Map 3.2). former has important nest habitat for herons, and 252 Although it is possible to make qualitative the latter is heavily nested by cormorants. The statements about the ecological implications if Northwest Staten Island/Harbor Herons SNWA sea level rise causes a total loss of habitat, our is an important nesting and foraging area for 253 ability to say what the impact might be if only a herons, ibises, egrets, gulls, and waterfowl. -

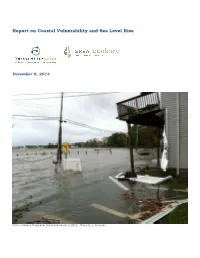

Report on Coastal Vulnerability and Sea Level Rise

Report on Coastal Vulnerability and Sea Level Rise December 8, 2014 Photo of Beach Road after Hurricane Sandy of 2012. Photo by: L. Konopko Report on Coastal Vulnerability and Sea Level Rise ThisThis Report was developed in consultation of the Town of Stony Point NYRCR Planning Committee Gurran Kane, Co-Chair Steven Scurti, Co-Chair Steve Beckerle Robert Burns Rebecca Casscles Wellington Casscles Supervisor Geoff Finn Luanne Konopko Kevin Maher Jim McDonnell Steve Porath Dominick Posillipo Rick Struck in cooperation with and with funding assistance byby:::: The New York Department of Environmental Conservation - Hudson River Estuary Program The New England Interstate Water Pollution Control Commission This information was prepared for the Hudson River Estuary program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, with support from the New York State Environmental Protection Fund, in cooperation with the New England Interstate Water Pollution Control Commission. The viewpoints expressed here do not necessarily represent those of NEIWPCC or NYSDEC, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or causes constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. 2 December 8, 2014 Report on Coastal Vulnerability and Sea Level Rise Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................................ 1 Purpose .................................................................................................................................................................................. -

The History Of

The History of 1 INDEX Introduction........................................................................................Page 3 The Hudson River & the Highlands……………………………………………….….…..Page 14 The Van Cortlandts – 1698 to 1853……………………………………………….….….Page 18 Louisa Sophia Ludlow – 1853 to 1876……………………………………………........Page 57 Louis W.Stevenson – 1876 to 1887………………………………………………..….….Page 91 Emma E. Stevenson – 1887 to 1899…………………………………………………....Page 142 Henry Jackson Morton Jr. – 1899 to 1901……………………………………………....Page 154 Ernest E. Slocum – 1901 to 1903………………………………………………….……Page 166 Greenhalge – 1903 to 1905……………………………………………………………..Page 168 Maud & William Boag – 1905 to 1914…………………………………………………..Page 174 Collin Kemper & Hope Latham – 1914 to 1942…………………………………………...Page 186 The Guiles – 1942 to 1952………………………………………………………….…Page 265 The Matzners – 1952 to 1966………………………………………………….....…..Page 274 The Cummings – 1966 to 1975……………………………………………………..….Page 285 GianninaPradella& Milan Olich – 1975 to 2005……………………………..………….Page 289 Richard Friedberg – 2005 to 2011………………………………………………..……Page 295 Arlene & Brent Perrott – 2011 to Present…………………………………………..…..Page 299 Myths, Legends and Ghosts……………………………………………………….….Page 303 2 INTRODUCTION Oldstone sits above the banks of the Hudson River, its gray, thick stone walls firmly anchored to the soil and rock of the Hudson Highlands. With Peekskill to the south, Bear Mountain Bridge and Westpoint just to the north, it is surrounded by some of the most beautiful and historic sites on the Hudson River. When Oldstone -

Windows on History

EXPLORING THE HUDSON RIVER VALLEY NATIONAL HERITAGE AREA Windows on History A rail journey through the Hudson River Valley, between New York City and Albany, is more than a trip from point A to point B. It’s a voyage through a landscape rich in history and beauty. Just look out the window… Na lley tion Va al r H e e v r i i t R a g n e o A s r d e u a H Na lley tion Va al r H e e v r i i t R a g n e o A s r d e u a H W ELCOME TO THE HUDSON RIVER VALLEY! RAVELING THROUGH THIS HISTORIC REGION, you will discover the people, places, and events that formed our national identity, and led Congress to designate the Hudson River Valley as a National Heritage Area in 1996. The Hudson River has also been designated one of our country’s Great American Rivers. TAs you journey between New York’s Pennsylvania station and the Albany- Rensselaer station, this guide will interpret the sites and features that you see out your train window, including historic sites that span three centuries of our nation’s history. You will also learn about the communities and cultural resources that are located only a short journey from the various This project was made station stops. possible through a partnership between the We invite you to explore the four million acres Hudson River Valley that make up the Hudson Valley and discover its National Heritage Area rich scenic, historic, cultural, and recreational and I Love NY. -

V-1 Reconstructing the Paleoecology Of

RECONSTRUCTING THE PALEOECOLOGY OF HAVERSTRAW TIDAL MARSHLANDS A Final Report of the Tibor T. Polgar Fellowship Program Lucy Gill Polgar Fellow Department of Ecology, Evolution and Environmental Biology Columbia University New York, NY 10027 Project Advisor: Dorothy Peteet Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory Columbia University Palisades, NY 10964 Gill, L. and D. Peteet. 2018. Reconstructing the Paleoecology of Haverstraw Tidal Marshlands. Section V:1-43 pp. In D.J. Yozzo, S.H. Fernald, and H. Andreyko (eds.), Final Reports of the Tibor T. Polgar Fellowship Program, 2015. Hudson River Foundation. V-1 ABSTRACT Climate change, a timely topic, cannot be understood solely by analyzing modern- day ecosystems. Sediment stratigraphy from tidal marshes is an important source of paleoecological data, as these ecosystems experience high rates of deposition and preserve organic material well. Although Hudson River Valley marshes have been extensively researched, work has focused on the four areas protected by the Hudson River National Estuarine Research Reserve (HRNERR). The marshlands of Haverstraw in Rockland County are comparable to the HRNERR sites in their capacity for biodiversity, carbon sequestration, and other important ecological functions. They are, however, understudied. This study uses loss-on-ignition and macrofossil analysis in combination with X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy to construct a high-resolution paleoenvironmental record. Biotic and geochemical zones have been identified and correlated with archaeological and historical data to assess the influence of anthropogenic activity in the area. The organic:inorganic maxima evidenced likely correspond to a pre- industrial period, characterized by burning events associated with increasing populations and concentrated settlement, as well as agricultural practices. -

Indian Point Unit 3 Revision 7 to Updated Final Safety Analysis

IP3 FSAR UPDATE CHAPTER 2 SITE AND ENVIRONMENT 2.1 SUMMARY OF CONCLUSIONS This Chapter sets forth the site and environmental data which together formed the basis for many of the criteria for designing the facility and for evaluating the routine and accidental releases of radioactive liquids and gases to the environment. These data support the conclusion that there will be no undue risk to public health and safety due to plant operation. The strength of this conclusion rests with these data and the determinations (also included in this report) of several independent consultants, each speaking within a particular area of expertise - health physics, demography, geology, seismology, hydrology or meteorology, as the case may be. The task of evaluating the environmental characteristics of the area was facilitated by the fact that more than 12 years of studies and measurements of environmental characteristics were undertaken. For over twenty years, measurements have been made of the effects on the environment of releases from at least one operating nuclear power facility at the Indian Point Site. Conservative projections have been made of the growth of population in the area and these projections have been taken into account in plant design and operation as to control the effects of accidents. Population estimates are presented in subchapter 2.4. The census data for 1990 reveals that the population within a 10-mile radius of the site was approximately 238,043 whereas the 2000 estimated population is 564,200. The land is now zoned principally for residential and state park usage although there is some industrial activity and a little agricultural and grazing activity. -

The Town of Haverstraw Waterfront & the Chair Factory Site

OUR SITE FOR THE SYMPOSIUM The Town of Haverstraw Waterfront & The Chair Factory Site HAVERSTRAW VILLAGE WATERFRONT Commuter Railroad Runs Along Here Village land area is 2 sq. miles with limited room to grow. Village also owns 3 sq. miles of Hudson River. Bounded by the Hudson River on the East & High Tor State Park on the West. To the South is the Ferry Landing & The Harbors Development and North is The Chair Factory Site. VILLAGE FAST FACTS RESIDENTS • 12,000 resiDents Commuter Railroad Runs Along Here • 2/3 sPeak SPanish as a first language • Diverse community with strong family anD community connecYons • The community has an intergeneraYonal make uP. ECONOMICS • Like many of the waterfront communiYes that thriveD in the 1900s it has suffereD with changes in the economy anD resource needs. LOCATION: BounDeD by the HuDson River on the East & High Tor State Park, Part of the Palisades Interstate Park System, on the West. To the North it extenDs to Bowline Park anD on the South to Tilcon Quarry. VILLAGE HISTORY A WATERFRONT COMMUNITY • The locaYon was a strategic Part of the American RevoluYon with lookouts PosteD on toP of High Tor (832 ^. tall). Commuter Railroad Runs Along Here Beacon fires were set when trooPs saw BriYsh shiPs heading uP the HuDson. • In the early 1900s this area was known as the “Brickmaking capital of the worlD” with 42 factories & 148 branDs. Historic Haverstraw Bay anD High Tor Mountain in the Haverstraw had all the necessary backgrounD. Image from the Village of Haverstraw Files. ingreDients: clay DePosits by the HuDson River water; the rich soil that lineD Haverstraw’s waterfront; anD an abunDance of straw. -

The Hudson Our Energy and Mineral Resources and Works to Assure That Their Development Is in the Best Interests of All Our People

As the Nation's principal conservation agency, the Department of the Interior has responsibility for most of our nationally owned River Basins of the public lands and natural resources. This includes fostering the United States: wisest use of our land and water resources, protecting our fish and wildlife, preserving the environmental and cultural values of our national parks and historical places, and providing for the enjoy ment of life through outdoor recreation. The Department assesses The Hudson our energy and mineral resources and works to assure that their development is in the best interests of all our people. The Depart ment also has a major responsibility for American Indian reservation communities and for people who live in Island Territories under U.S. administration. U.S. Department of the Interior/Geological Survey River Basins of the United States: The Hudson This leaflet, one of a series on the river basins of the United States, contains information on the Hudson River Basin, including a brief early history, a description of the physical characteristics, and other statistical data. At present, other river basins included in the series are The Colorado, The Columbia, The Delaware, The Potomac, and The Wabash. Early Exploration and Settlement The Hudson was discovered in 1524 by Giovanni da Verrazano, an Italian sailor. In 1609, Henry Hudson, an English sea captain working for the Dutch East India Company, Mouth miles south of Albany. For 16 miles, it winds was first to explore the river upstream. through a narrow valley with high and rocky The mouth of the Hudson is in the Upper Indians living on the banks called it shores of great beauty that is sometimes New York Bay. -

Restoring Oysters to Urban Waters

RESTORING OYSTERS TO URBAN WATERS Lessons Learned and Future Opportunities in NY/NJ Harbor ABOUT THE NATURE CONSERVANCY The mission of The Nature Conservancy (TNC) is to conserve the lands and waters on which all life depends. TNC’s New York City Program protects and promotes nature and environmental solutions to restore natural systems and enhance the quality of life of all New Yorkers. We are committed to improving the City’s air, land, and water, and we advance strategies that create a healthy, resilient, and sustainable urban environment. ABOUT BILLION OYSTER PROJECT Billion Oyster Project is a nonprofit organization on a mission to restore oyster reefs to New York Harbor through public education initiatives. Founded on the belief that restoration without edu- cation is temporary, and observing that learning outcomes improve when students have the op- portunity to work on real restoration projects, collaborating with public schools is fundamental to Billion Oyster Project’s work. Billion Oyster Project engages The Urban Assembly New York Harbor School and thousands of students across the five boroughs in restoration projects using discarded oyster shells from New York City restaurants. To date, Billion Oyster Project and partners have restored 28 million oysters to New York Harbor. ABOUT THE PARTNERSHIP Billion Oyster Project and The Nature Conservancy have partnered to restore the health of New York Harbor. Billion Oyster Project is working to restore oyster reefs through public education initiatives, partnering with The Nature Conservancy, as a scientific adviser, to measure oyster health, water quality, and biodiversity. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This document received technical input and review from Anna Bartlett, Bryan DeAngelis, Kristin France, Emily Maxwell, and Ellen Weiss of TNC; Liz Burmester and Katie Mosher of Billion Project; Jim Lodge of the Hudson River Foundation; and Phil Silva of Central Park Conservancy.