Early Season Softwood Cuttings Effective for Vegetative Propagation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

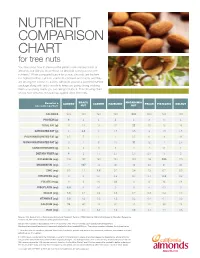

Nutrient Comparison Chart

NUTRIENT COMPARISON CHART for tree nuts You may know how to measure the perfect one-ounce portion of almonds, but did you know those 23 almonds come packed with nutrients? When compared ounce for ounce, almonds are the tree nut highest in fiber, calcium, vitamin E, riboflavin and niacin, and they are among the lowest in calories. Almonds provide a powerful nutrient package along with tasty crunch to keep you going strong, making them a satisfying snack you can feel good about. The following chart shows how almonds measure up against other tree nuts. BRAZIL MACADAMIA Based on a ALMOND CASHEW HAZELNUT PECAN PISTACHIO WALNUT one-ounce portion1 NUT NUT CALORIES 1602 190 160 180 200 200 160 190 PROTEIN (g) 6 4 4 4 2 3 6 4 TOTAL FAT (g) 14 19 13 17 22 20 13 19 SATURATED FAT (g) 1 4.5 3 1.5 3.5 2 1.5 1.5 POLYUNSATURATED FAT (g) 3.5 7 2 2 0.5 6 4 13 MONOUNSATURATED FAT (g) 9 7 8 13 17 12 7 2.5 CARBOHYDRATES (g) 6 3 9 5 4 4 8 4 DIETARY FIBER (g) 4 2 1.5 2.5 2.5 2.5 3 2 POTASSIUM (mg) 208 187 160 193 103 116 285 125 MAGNESIUM (mg) 77 107 74 46 33 34 31 45 ZINC (mg) 0.9 1.2 1.6 0.7 0.4 1.3 0.7 0.9 VITAMIN B6 (mg) 0 0 0.1 0.2 0.1 0.1 0.3 0.2 FOLATE (mcg) 12 6 20 32 3 6 14 28 RIBOFLAVIN (mg) 0.3 0 0.1 0 0 0 0.1 0 NIACIN (mg) 1.0 0.1 0.4 0.5 0.7 0.3 0.4 0.3 VITAMIN E (mg) 7.3 1.6 0.3 4.3 0.2 0.4 0.7 0.2 CALCIUM (mg) 76 45 13 32 20 20 30 28 IRON (mg) 1.1 0.7 1.7 1.3 0.8 0.7 1.1 0.8 Source: U.S. -

Health Benefits of Pistachio Consumption in Pre-Diabetic Subjects

HEALTH BENEFITS OF PISTACHIO CONSUMPTION IN PRE-DIABETIC SUBJECTS Pablo Hernández Alonso ADVERTIMENT. L'accés als continguts d'aquesta tesi doctoral i la seva utilització ha de respectar els drets de la persona autora. Pot ser utilitzada per a consulta o estudi personal, així com en activitats o materials d'investigació i docència en els termes establerts a l'art. 32 del Text Refós de la Llei de Propietat Intel·lectual (RDL 1/1996). Per altres utilitzacions es requereix l'autorització prèvia i expressa de la persona autora. En qualsevol cas, en la utilització dels seus continguts caldrà indicar de forma clara el nom i cognoms de la persona autora i el títol de la tesi doctoral. No s'autoritza la seva reproducció o altres formes d'explotació efectuades amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva comunicació pública des d'un lloc aliè al servei TDX. Tampoc s'autoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant als continguts de la tesi com als seus resums i índexs. ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis doctoral y su utilización debe respetar los derechos de la persona autora. Puede ser utilizada para consulta o estudio personal, así como en actividades o materiales de investigación y docencia en los términos establecidos en el art. 32 del Texto Refundido de la Ley de Propiedad Intelectual (RDL 1/1996). Para otros usos se requiere la autorización previa y expresa de la persona autora. En cualquier caso, en la utilización de sus contenidos se deberá indicar de forma clara el nombre y apellidos de la persona autora y el título de la tesis doctoral. -

Conservation and Management of Butternut Trees

Purdue University Purdue extension FNR-421-W & Natural Re ry sou Forestry and Natural Resources st rc re e o s F Conservation and Management of Butternut Trees Lenny Farlee1,3, Keith Woeste1, Michael Ostry2, James McKenna1 and Sally Weeks3 1 USDA Forest Service Hardwood Tree Improvement and Regeneration Center, Purdue University, 715 W. State Street, West Lafayette, IN, 47907 PURDUE UNIVERSITY 2 USDA Forest Service Northern Research Station, 1561 Lindig Ave. St. Paul, MN 55108 3 Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, Purdue University, 715 W. State Street, West Lafayette, IN, 47907 Introduction Butternut (Juglans cinerea), also known as white wal- nut, is a native hardwood related to black walnut (Juglans nigra) and other members of the walnut family. Butternut is a medium-sized tree with alternate, pinnately com- pound leaves, that bears large, sharply ridged, cylindrical nuts inside sticky green hulls that earned it the nickname lemon-nut (Rink, 1990). The nuts, a preferred food of squirrels and other wildlife, were collected and eaten by Native Americans (Waugh, 1916; Hamel and Chiltoskey, 1975) and early settlers, who also valued butternut for its workable, medium brown-colored heartwood (Kel- logg, 1919), and as a source of medicine (Johnson, 1884; Lawrence, 1998), dyes (Hamel and Chiltoskey, 1975), and sap sugar. Butternut’s native range extends over the entire north- eastern quarter of the United States, including many states immediately west of the Mississippi River. Butter- nut is more cold-tolerant than black walnut, and it grows as far north as the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, New Brunswick, southern Quebec, and Ontario (Fig.1). -

Conservation Assessment for Butternut Or White Walnut (Juglans Cinerea) L. USDA Forest Service, Eastern Region

Conservation Assessment for Butternut or White walnut (Juglans cinerea) L. USDA Forest Service, Eastern Region 2003 Jan Schultz Hiawatha National Forest Forest Plant Ecologist (906) 228-8491 This Conservation Assessment was prepared to compile the published and unpublished information on Juglans cinerea L. (butternut). This is an administrative review of existing information only and does not represent a management decision or direction by the U. S. Forest Service. Though the best scientific information available was gathered and reported in preparation of this document, then subsequently reviewed by subject experts, it is expected that new information will arise. In the spirit of continuous learning and adaptive management, if the reader has information that will assist in conserving the subject taxon, please contact the Eastern Region of the Forest Service Threatened and Endangered Species Program at 310 Wisconsin Avenue, Milwaukee, Wisconsin 53203. Conservation Assessment for Butternut or White walnut (Juglans cinerea) L. 2 Table Of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .....................................................................................5 INTRODUCTION / OBJECTIVES.......................................................................7 BIOLOGICAL AND GEOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION..............................8 Species Description and Life History..........................................................................................8 SPECIES CHARACTERISTICS...........................................................................9 -

Juglans Nigra Juglandaceae L

Juglans nigra L. Juglandaceae LOCAL NAMES English (walnut,American walnut,eastern black walnut,black walnut); French (noyer noir); German (schwarze Walnuß); Portuguese (nogueira- preta); Spanish (nogal negro,nogal Americano) BOTANIC DESCRIPTION Black walnut is a deciduous tree that grows to a height of 46 m but ordinarily grows to around 25 m and up to 102 cm dbh. Black walnut develops a long, smooth trunk and a small rounded crown. In the open, the trunk forks low with a few ascending and spreading coarse branches. (Robert H. Mohlenbrock. USDA NRCS. The root system usually consists of a deep taproot and several wide- 1995. Northeast wetland flora: Field office spreading lateral roots. guide to plant species) Leaves alternate, pinnately compound, 30-70 cm long, up to 23 leaflets, leaflets are up to 13 cm long, serrated, dark green with a yellow fall colour in autumn and emits a pleasant sweet though resinous smell when crushed or bruised. Flowers monoecious, male flowers catkins, small scaley, cone-like buds; female flowers up to 8-flowered spikes. Fruit a drupe-like nut surrounded by a fleshy, indehiscent exocarp. The nut has a rough, furrowed, hard shell that protects the edible seed. Fruits Bark (Robert H. Mohlenbrock. USDA NRCS. 1995. Northeast wetland flora: Field office produced in clusters of 2-3 and borne on the terminals of the current guide to plant species) season's growth. The seed is sweet, oily and high in protein. The bitter tasting bark on young trees is dark and scaly becoming darker with rounded intersecting ridges on maturity. BIOLOGY Flowers begin to appear mid-April in the south and progressively later until early June in the northern part of the natural range. -

Comparative Proteomic Analysis of Walnut (Juglans Regia L.) Pellicle Tissues Reveals the Regulation of Nut Quality Attributes

life Article Comparative Proteomic Analysis of Walnut (Juglans regia L.) Pellicle Tissues Reveals the Regulation of Nut Quality Attributes Paulo A. Zaini 1, Noah G. Feinberg 1, Filipa S. Grilo 2 , Houston J. Saxe 1 , Michelle R. Salemi 3, Brett S. Phinney 3 , Carlos H. Crisosto 1 and Abhaya M. Dandekar 1,* 1 Department of Plant Sciences, University of California, Davis, CA 95616, USA; [email protected] (P.A.Z.); [email protected] (N.G.F.); [email protected] (H.J.S.); [email protected] (C.H.C.) 2 Department of Food Sciences and Technology, University of California, Davis, CA 95616, USA; [email protected] 3 Proteomics Core Facility, University of California, Davis, CA 95616, USA; [email protected] (M.R.S.); [email protected] (B.S.P.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 2 November 2020; Accepted: 25 November 2020; Published: 27 November 2020 Abstract: Walnuts (Juglans regia L.) are a valuable dietary source of polyphenols and lipids, with increasing worldwide consumption. California is a major producer, with ‘Chandler’ and ‘Tulare’ among the cultivars more widely grown. ‘Chandler’ produces kernels with extra light color at a higher frequency than other cultivars, gaining preference by growers and consumers. Here we performed a deep comparative proteome analysis of kernel pellicle tissue from these two valued genotypes at three harvest maturities, detecting a total of 4937 J. regia proteins. Late and early maturity stages were compared for each cultivar, revealing many developmental responses common or specific for each cultivar. Top protein biomarkers for each developmental stage were also selected based on larger fold-change differences and lower variance among replicates, including proteins for biosynthesis of lipids and phenols, defense-related proteins and desiccation stress-related proteins. -

Juglans Spp., Juglone and Allelopathy

AllelopathyJournatT(l) l-55 (2000) O Inrernationa,^,,r,':'r::;:';::::,:rt;SS Juglansspp., juglone and allelopathy R.J.WILLIS Schoolof Botany.L.iniversity of Melbourre,Parkville, Victoria 3052, ALrstr.alia (Receivedin revisedform : February 26.1999) CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2. HistoricalBackground 3. The Effectsof walnutson otherplants 3.i. Juglansnigra 3.1.1.Effects on cropplants 3. I .2. Eft'ectson co-plantedtrees 3. 1 .3 . Effectson naturalvegetation 3.2. Juglansregia 3.2.1. Effectson otherplalrts 3.2.2.Effects on phytoplankton 1.3. Othel walnuts : Juglans'cinerea, J. ntttlor.J. mandshw-icu 4. Juglone 5. Variability in the effect of walnut 5.1. Intraspecificand Interspecific variation 5.2. Seasonalvariation 5.3 Variation in the effect of Juglansnigra on other.plants 5.4. Soil effects 6. Discussion Ke1'rvords: Allelopathy,crops, history, Juglan.s spp., juglone. phytoplankton,walnut, soil, TTCCS 1. INTRODUCTION The"rvalnuts" are referable to Juglans,a genusof 20-25species with a naturaldistribution acrossthe Northern Hemisphere and extending into SouthAmerica. Juglans is a memberof thefamily Juglandaceae which contains6 or 7 additionalgenera including Cruv,a, Cryptocctrva and a total of about 60 species. Walnuts are corrunerciallyimportant as the sourceof the ediblewalnut, the highly prizedtimber and as a specimentrees. Eating walnutsare usually obtarnedfrom -/. regia (the colrunonor Persianwalnut, erroneousll'known as the English walnut)- a nativeof SEEurope and Asia, which haslong been cultivated, but arealso sometin.res availablelocally from other speciessuch as J. nigra (back walnut) - a native of eastern North America andJ. ntajor, J. calfornica andJ. hindsii, native to the u,esternu.S. ILillis Grafting of supcrior fnrit-bearing scions of J. regia onlo rootstocksof hlrdier spccics. -

Curriculum Vitae Name

CURRICULUM VITAE NAME Kirk Broders ADDRESS PHONE Bioagricultural Sciences and Pest Management (970) 491-0850 College of Agricultural Sciences EDUCATION 2008 Ph D, The Ohio State University 2004 BS, University of Nebraska-Lincoln ACADEMIC POSITIONS 2017-2018 - Assistant Professor (College of Agricultural Sciences) 2016-2017 - Assistant Professor (College of Agricultural Sciences) 2015-2016 (College of Agricultural Sciences) OTHER POSITIONS August 2015 - Present Assistant Professor, BSPM, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, United States. 2011 - 2015 Assistant Professor, University of New Hampshire, United States. 2009 - 2010 Post-doctoral Research Fellow, University of Guelph, United States. PUBLISHED WORKS Refereed Journal Articles Broders, K. D., Munck, I., Wyka, S., Iriarte, G., Beaudoin, E. (2015). Characterization of Fungal Pathogens Associated with White Pine Needle Damage (WPND) in Northeastern North America. Forests, 6(11), 4088-4104., Peer Reviewed/Refereed Munck, I. A., Livingston, W., Lombard, K., Luther, T., Ostrofsky, W. D., Weimer, J., Wyka, S., Broders, K. D. (2015). Extent and Severity of Caliciopsis Canker in New England, USA: An Emerging Disease of Eastern White Pine (Pinus strobus L.). Forests, 6(11), 4360-4373., Peer Reviewed/Refereed Boraks, A. W., Broders, K. D. (in press). Population genetics of butternut (Juglans cinerea) in the northeastern United States. Conservation Genetics., Peer Reviewed/Refereed Laflamme, G., Broders, K. D., Côté, C., Munck, I., Iriarte, G., Innes, L. (2015). Priority of Lophophacidium over Canavirgella: taxonomic status of Lophophacidium dooksii and Canavirgella banfieldii, causal agents of a white pine needle disease. Mycologia, 107(4), 745-753., Peer Reviewed/Refereed Broders, K. D., Boraks, A., Barbison, L., Brown, J. R., Boland, G. -

Health and Nutrition Research

Health and Nutrition Research Pistachios can help individuals maintain good health, support an active lifestyle and reduce the risk of nutrition-related diseases. Research studies suggest that pistachios have numerous health benefits, including being a source of health-boosting antioxidants and other important nutrients, lowering the risk of heart disease, supporting weight management and a healthy diet, creating a lower-than-expected blood-sugar level and helping with insulin sensitivity. Subjects who ate more than three servings of nuts (such as pistachios) per week had a 39% lower mortality risk. The PREDIMED Study. Guasch-Ferré, et al. BMC medicine 2013Jul16; 11:164 AmericanPistachios.org Pistachios and Mortality Many large population studies have found an inverse association between nut intake and total mortality. Recently published in the British Journal of Nutrition, nut intake was associated with a lower risk of all-cause mortality in a large prospective study of 19,386 participants. As compared with subjects who did not eat nuts, those who consumed nuts more than 8 times per month showed a 47% lower risk of dying from any cause.1 Similar results have been found in studies from populations around the world.2 An analysis of studies for all-cause, cancer and cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality, with a total of 354,933 participants, nut consumption was associated with significant protection. One-serving of nuts per day resulted in 27% lower risk from dying from any cause including CVD and cancer.3 In another systematic review and analysis of large, well-designed prospective population studies in Europe and North America showed that nut consumption is inversely associated with all-cause mortality, total CVD mortality, coronary heart disease mortality and sudden cardia death. -

To See a List of Possible Ice Cream Choices

After Dinner Mint Almond Almond Crisp (w peanuts and rice cereal) Almond Delight Almond Linzertorte (w raspberry jam) Almond Poppy Seed Ambrosia (Banana Ice Cream w coconut, orange and almonds) Anise Apple Brown Betty (w ginger snaps) Apple Butter Apple Cheddar Apple Cherry Apple Cinnamon Coffee Cake Apple Pie Apple Raisin Walnut Apple Strawberry Apple Thyme Applesauce Apricot Apricot Almond Apricot Jam Apricot Orange Asia Spice (Green Tea ice cream w szechuan peppercorns) Autumn (Nutmeg ice cream w prunes, dates & figs) Avocado Aztec "Hot" Chocolate (Chocolate w chile powder) Baked Apple Balsamic Caramel (w balsamic vinegar) Banana Banana Candy Bar Banana Carob Chip Banana Chocolate Chip Banana Coconut Banana Cookie Banana Cream Pie Banana Fudge Banana Fudge Chunk Banana Malt Banana Marshmellow Banana Nut Banana Orange Banana Peanut Butter Banana Philadelphia Style ( w/o eggs) Banana Strawberry Banana Tart Banana w Caramelized White Chocolate Freckles Bangkok Peanut Beet w Mascarpone, Orange Zest & Poppy Seeds Basil Page 1 Beet w Mascarpone, Orange Zest & Poppy Seeds Berry Crisp Birthday Cake Biscuit Tortoni Bittersweet Chocolate-Laced Vanilla Black Coffee Black Currant Tea Black Pepper Black Pine (Pine Nut ice cream w black licorice candy) Black Walnut Blackberry Blackberry Jam Blackstrap Praline (w blackstrap molasses) Blueberry Blueberry Jam Blueberry Lemon Sour Cream Brown Bread Brown Butter Almond Brittle Bubble Gum Burnt Almond Burnt Sugar Burnt Sugar Pie Burnt Walnut Butter Cake, Gooey Butter Fruitcake Butter Pecan Butter w Honey -

Identification of Butternuts and Butternut Hybrids

Purdue University Purdue extension FNR-420-W & Natural Re ry sou Forestry and Natural Resources st rc re e o s F Identification of Butternuts and Butternut Hybrids Lenny Farlee1,3, Keith Woeste1, Michael Ostry2, James McKenna1 and Sally Weeks3 1 USDA Forest Service Hardwood Tree Improvement and Regeneration Center, Purdue University, 715 W. State Street, West Lafayette, IN, 47907 PURDUE UNIVERSITY 2 USDA Forest Service Northern Research Station, 1561 Lindig Ave. St. Paul, MN 55108 3 Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, Purdue University, 715 W. State Street, West Lafayette, IN, 47907 Introduction Butternut (Juglans cinerea), also known as white walnut, is a native hardwood related to black walnut (Juglans nigra) and other members of the walnut family. Butternut is a medium-sized tree with alternate, pinnately compound leaves that bears large, sharply ridged and corrugated, elongated, cylindrical nuts born inside sticky green hulls that earned it the nickname lemon-nut (Rink, 1990). The nuts are a preferred food of squirrels and other wildlife. Butternuts were collected and eaten by Native Americans (Waugh, 1916; Hamel and Chiltoskey, 1975) and early settlers, who also valued butternut for its workable, medium brown-colored wood (Kellogg, 1919), and as a source of medicine (Johnson, 1884), dyes (Hamel and Chiltoskey, 1975), and sap sugar. Butternut’s native range extends over the entire north- eastern quarter of the United States, including many states immediately west of the Mississippi River, and into Canada. Butternut is more cold-tolerant than black walnut, and it grows as far north as the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, New Brunswick, southern Quebec, and Figure 1. -

Raw and Roasted Pistachio Nuts (Pistacia Vera L.) Are ‘Good’ Sources of Protein Based on Their Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score As Determined in Pigs

Research Article Received: 12 September 2019 Revised: 13 April 2020 Accepted article published: 23 April 2020 Published online in Wiley Online Library: 19 May 2020 (wileyonlinelibrary.com) DOI 10.1002/jsfa.10429 Raw and roasted pistachio nuts (Pistacia vera L.) are ‘good’ sources of protein based on their digestible indispensable amino acid score as determined in pigs Hannah M Bailey and Hans H Stein* Abstract BACKGROUND: Pistachio nuts may be consumed as raw nuts or as roasted nuts. However, there is limited information about the protein quality of the nuts, and amino acid (AA) digestibility and protein quality have not been reported. Therefore, the objec- tive of this research was to test the hypothesis that raw and roasted pistachio nuts have a digestible indispensable AA score (DIAAS) and a protein digestibility corrected AA score (PDCAAS) greater than 75, thereby qualifying them as a good source of protein. RESULTS: The standardized ileal digestibility (SID) of all indispensable AAs, except arginine and phenylalanine, was less in roasted pistachio nuts than in raw pistachio nuts (P < 0.05). Raw pistachio nuts had a PDCAAS of 73, and roasted pistachio nuts had a PDCAAS of 81, calculated for children 2–5 years, and the limiting AA in the PDCAAS calculation was threonine. The DIAAS values calculated for children older than 3 years, adolescents, and adults was 86 and 83 for raw and roasted pistachio nuts respectively. The limiting AA in both raw and roasted pistachio nuts that determined the DIAAS for this age group was lysine. CONCLUSION: The results of this research illustrate that raw and roasted pistachio nuts can be considered a good quality pro- tein source with DIAAS greater than 75; however, processing conditions associated with roasting may decrease the digestibility of AAs in pistachio nuts.