The Other Neng

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Umithesis Lye Feedingghosts.Pdf

UMI Number: 3351397 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ______________________________________________________________ UMI Microform 3351397 Copyright 2009 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. _______________________________________________________________ ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS vi INTRODUCTION The Yuqie yankou – Present and Past, Imagined and Performed 1 The Performed Yuqie yankou Rite 4 The Historical and Contemporary Contexts of the Yuqie yankou 7 The Yuqie yankou at Puti Cloister, Malaysia 11 Controlling the Present, Negotiating the Future 16 Textual and Ethnographical Research 19 Layout of Dissertation and Chapter Synopses 26 CHAPTER ONE Theory and Practice, Impressions and Realities 37 Literature Review: Contemporary Scholarly Treatments of the Yuqie yankou Rite 39 Western Impressions, Asian Realities 61 CHAPTER TWO Material Yuqie yankou – Its Cast, Vocals, Instrumentation -

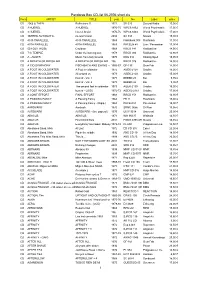

Pandoras Box CD-List 06-2006 Short

Pandoras Box CD-list 06-2006 short.xls Form ARTIST TITLE year No Label price CD 2066 & THEN Reflections !! 1971 SB 025 Second Battle 15,00 € CD 3 HUEREL 3 HUEREL 1970-75 WPC6 8462 World Psychedelic 17,00 € CD 3 HUEREL Huerel Arisivi 1970-75 WPC6 8463 World Psychedelic 17,00 € CD 3SPEED AUTOMATIC no man's land 2004 SA 333 Nasoni 15,00 € CD 49 th PARALLELL 49 th PARALLELL 1969 Flashback 008 Flashback 11,90 € CD 49TH PARALLEL 49TH PARALLEL 1969 PACELN 48 Lion / Pacemaker 17,90 € CD 50 FOOT HOSE Cauldron 1968 RRCD 141 Radioactive 14,90 € CD 7 th TEMPLE Under the burning sun 1978 RRCD 084 Radioactive 14,90 € CD A - AUSTR Music from holy Ground 1970 KSG 014 Kissing Spell 19,95 € CD A BREATH OF FRESH AIR A BREATH OF FRESH AIR 196 RRCD 076 Radioactive 14,90 € CD A CID SYMPHONY FISCHBACH AND EWING - (21966CD) -67 GF-135 Gear Fab 14,90 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER A Foot in coldwater 1972 AGEK-2158 Unidisc 15,00 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER All around us 1973 AGEK-2160 Unidisc 15,00 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER best of - Vol. 1 1973 BEBBD 25 Bei 9,95 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER best of - Vol. 2 1973 BEBBD 26 Bei 9,95 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER The second foot in coldwater 1973 AGEK-2159 Unidisc 15,00 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER best of - (2CD) 1972-73 AGEK2-2161 Unidisc 17,90 € CD A JOINT EFFORT FINAL EFFORT 1968 RRCD 153 Radioactive 14,90 € CD A PASSING FANCY A Passing Fancy 1968 FB 11 Flashback 15,00 € CD A PASSING FANCY A Passing Fancy - (Digip.) 1968 PACE-034 Pacemaker 15,90 € CD AARDVARK Aardvark 1970 SRMC 0056 Si-Wan 19,95 € CD AARDVARK AARDVARK - (lim. -

NEW YORK EDITED PAPER-Dhriti

Fifth Century Common Era Reorienting Chinese Buddhist Monastic Tradition Redefining India-China Buddhist Monastic Relations - A Critical Study Introduction: The following paper shares the findings of an ongoing study. The study is still not complete and therefore does not yet propose a final conclusion. An abstract pattern in relation to the evolution of Buddhist monasticism along a certain trajectory, through centuries of Chinese Buddhist evolutionary history, which the study has been able to identify, has been presented here. This paper makes the proposition that fifth century CE was a distinctive period in the history of Buddhist monasticism in China, that it was a period in Chinese Buddhist history, which, owing to certain complex processes related to the gradual infiltration, permeation, adaptation, and assimilation of Buddhism into the foreign socio-cultural-political milieu of China, as against reactions over its interactions with the state and indigenous Chinese schools of thought, effected a re-orientation of the Chinese Buddhist monastic tradition and eventually redefined India-China Buddhist monastic relations. The study proposes that fifth century Buddhist monastic culture in China was influenced by certain emerging issues of the time, namely popularization of the relic veneration cult, growing interactions between the imperial house and the Buddhist clergy, permeation of Buddhist teachings into immigrant Chinese gentry circles in the south, wide circulation of apologetic and propagandistic literature, rise of messianic figures influenced by Buddhist and Daoist eschatological ideas and most importantly the institutionalization of Buddhist monastic disciplinary codes (vinaya), some of which perhaps paved the trajectory along which monasticism in China evolved through the centuries that followed. -

The Reception and Translation of Classical Chinese Poetry in English

NCUE Journal of Humanities Vol. 6, pp. 47-64 September, 2012 The Reception and Translation of Classical Chinese Poetry in English Chia-hui Liao∗ Abstract Translation and reception are inseparable. Translation helps disseminate foreign literature in the target system. An evident example is Ezra Pound’s translation based on the 8th-century Chinese poet Li Bo’s “The River-Merchant’s Wife,” which has been anthologised in Anglophone literature. Through a diachronic survey of the translation of classical Chinese poetry in English, the current paper places emphasis on the interaction between the translation and the target socio-cultural context. It attempts to stress that translation occurs in a context—a translated work is not autonomous and isolated from the literary, cultural, social, and political activities of the receiving end. Keywords: poetry translation, context, reception, target system, publishing phenomenon ∗ Adjunct Lecturer, Department of English, National Changhua University of Education. Received December 30, 2011; accepted March 21, 2012; last revised May 13, 2012. 47 國立彰化師範大學文學院學報 第六期,頁 47-64 二○一二年九月 中詩英譯與接受現象 廖佳慧∗ 摘要 研究翻譯作品,必得研究其在譯入環境中的接受反應。透過翻譯,外國文學在 目的系統中廣宣流布。龐德的〈河商之妻〉(譯寫自李白的〈長干行〉)即一代表實 例,至今仍被納入英美文學選集中。藉由中詩英譯的歷時調查,本文側重譯作與譯 入文境間的互動,審視前者與後者的社會文化間的關係。本文強調翻譯行為的發生 與接受一方的時代背景相互作用。譯作不會憑空出現,亦不會在目的環境中形成封 閉的狀態,而是與文學、文化、社會與政治等活動彼此交流、影響。 關鍵字:詩詞翻譯、文境、接受反應、目的/譯入系統、出版現象 ∗ 國立彰化師範大學英語系兼任講師。 到稿日期:2011 年 12 月 30 日;確定刊登日期:2012 年 3 月 21 日;最後修訂日期:2012 年 5 月 13 日。 48 The Reception and Translation of Classical Chinese Poetry in English Writing does not happen in a vacuum, it happens in a context and the process of translating texts form one cultural system into another is not a neutral, innocent, transparent activity. -

Article N°70 De Sagesse Ancienne Kut-Humi

Article n°70 de Sagesse Ancienne Kut-Humi David Goulois extrait du site : www.sagesseancienne.com (Tous droits réservés : voir conditions en page d’accueil) Parmi les nombreuses attaques dont HPB a fait l'objet, l'une d'elles consistait à affirmer qu'elle avait inventé l'existence des Maîtres de Sagesse. Or, ces derniers existent bel et bien. Antérieurement, nous avons déjà démontré que le concept de Maîtres existe depuis toujours dans les traditions spirituelles. Non seulement ce concept ne s'oppose pas à ces traditions spirituelles, mais les Maîtres ont entièrement fondé ces dernières. Ainsi, lorsque les esprits matérialistes nient l'existence des Maîtres de Sagesse, des Mahatmas, des Bodhisattvas, des Xian Ren, des Dieux mythiques, des Saints, des Yogis réalisés spirituellement (ou tout autre nom que les religions et philosophies ont bien voulu leur donner), cela prouve au moins trois choses : ces esprits sceptiques ne comprennent pas l'essence des traditions spirituelles, ils ignorent la réalité ésotérique de la vie, et ils démontrent qu'ils ne sont pas en contact avec les Maîtres de Sagesse. La Sagesse Ancienne, la Doctrine Secrète, la Philosophie Eternelle, la Tradition Primordiale, tous ces vocables et bien d'autres encore évoquent l'idée d'une sagesse universelle, commune à tous les peuples et à toutes les époques. Les Maîtres sont à l'origine de la Sagesse Ancienne et en ont toujours assuré la cohésion et la pérennité. Aucun véritable ésotérisme n'est envisageable dès lors qu'on nie l'existence de ces Hommes et de ces Femmes parfaits, car la philosophie ésotérique et l'ascèse qui en découle n'ont fondamentalement qu'un seul but : la réalisation du Soi, avec pour conséquence l'accès à l'immortalité. -

How Could Phenological Records from the Chinese Poems of the Tang and Song Dynasties

https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-2020-122 Preprint. Discussion started: 28 September 2020 c Author(s) 2020. CC BY 4.0 License. How could phenological records from the Chinese poems of the Tang and Song Dynasties (618-1260 AD) be reliable evidence of past climate changes? Yachen Liu1, Xiuqi Fang2, Junhu Dai3, Huanjiong Wang3, Zexing Tao3 5 1School of Biological and Environmental Engineering, Xi’an University, Xi’an, 710065, China 2Faculty of Geographical Science, Key Laboratory of Environment Change and Natural Disaster MOE, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, 100875, China 3Key Laboratory of Land Surface Pattern and Simulation, Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Chinese Academy of Science (CAS), Beijing, 100101, China 10 Correspondence to: Zexing Tao ([email protected]) Abstract. Phenological records in historical documents have been proved to be of unique value for reconstructing past climate changes. As a literary genre, poetry reached its peak period in the Tang and Song Dynasties (618-1260 AD) in China, which could provide abundant phenological records in this period when lacking phenological observations. However, the reliability of phenological records from 15 poems as well as their processing methods remains to be comprehensively summarized and discussed. In this paper, after introducing the certainties and uncertainties of phenological information in poems, the key processing steps and methods for deriving phenological records from poems and using them in past climate change studies were discussed: -

Beyond Buddhist Apology the Political Use of Buddhism by Emperor Wu of the Liang Dynasty

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Ghent University Academic Bibliography Beyond Buddhist Apology The Political Use of Buddhism by Emperor Wu of the Liang Dynasty (r.502-549) Tom De Rauw ii To my daughter Pauline, the most wonderful distraction one could ever wish for and to my grandfather, a cakravartin who ruled his own private universe iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Although the writing of a doctoral dissertation is an individual endeavour in nature, it certainly does not come about from the efforts of one individual alone. The present dissertation owes much of its existence to the help of the many people who have guided my research over the years. My heartfelt thanks, first of all, go to Dr. Ann Heirman, who supervised this thesis. Her patient guidance has been of invaluable help. Thanks also to Dr. Bart Dessein and Dr. Christophe Vielle for their help in steering this thesis in the right direction. I also thank Dr. Chen Jinhua, Dr. Andreas Janousch and Dr. Thomas Jansen for providing me with some of their research and for sharing their insights with me. My fellow students Dr. Mathieu Torck, Leslie De Vries, Mieke Matthyssen, Silke Geffcken, Evelien Vandenhaute, Esther Guggenmos, Gudrun Pinte and all my good friends who have lent me their listening ears, and have given steady support and encouragement. To my wife, who has had to endure an often absent-minded husband during these first years of marriage, I acknowledge a huge debt of gratitude. She was my mentor in all but the academic aspects of this thesis. -

Buddhist Growth in China

Piya Tan SD 40b.1 How Buddhism Became Chinese How Buddhism Became Chinese 1 A reflection on the (Ahita) Thera Sutta (A 5.88) by Piya Tan ©2008 (2nd rev), 2009 (3rd rev) Even famous teachers can have wrong views and mislead others. (A 5.88) The (Ahitāya) Thera Sutta (A 5.88) is a vital warning that grounding in right view is imperative especially when we are presenting or representing the Buddha Dharma. The more people respect us, or listen to us, or turn to us for spiritual help, and the more we have the means of mass-propagating our Buddhist views, the more carefully we have to ascertain rightness and moral consequences of our efforts. The point is that status, learning, seniority, fame, wealth, and resources, advantageous as they may be in Buddhist work, are not sufficient standards for truth. While it is true that whatever we express are merely our own opinions, we must have the moral re- sponsibility at least to ensure that such opinions or facts reflect the true Dharma. Much as we have the freedom to publicize the teachings of a particular teacher or group, we must accept the fact that this may not be the only view of the true Dharma. The final test of what we propagate must be Dharma-based. The true teachings always stand above the teacher.1 After the Buddha‘s time, especially as Buddhism grows beyond India, such standards are not always possible, for various reasons. At first, Buddhism appears to change the culture, but in due course it is the culture that changes Buddhism, often turning it into a system vastly different, even contrary to the Dhar- ma of the Buddha. -

The Record of Linji

(Continued from front fl ap) EAST ASIAN RELIGION SASAKI the record of translation and appeared contain the type of detailed his- and The Linji lu (Record of Linji) has been “This new edition will be the translation of choice for Western Zen commentary by torical, linguistic, and doctrinal annota- KIRCHNER an essential text of Chinese and Japanese tion that was central to Mrs. Sasaki’s plan. communities, college courses, and all who want to know Ruth Fuller Sasaki Zen Buddhism for nearly a thousand years. that the translation they are reading is faithful to the original. A compilation of sermons, statements, and The materials assembled by Mrs. Sasaki Professional scholars of Buddhism will revel in the sheer edited by acts attributed to the great Chinese Zen and her team are fi nally available in the wealth of information packed into footnotes and bibliographical LINJI master Linji Yixuan (d. 866), it serves as Thomas Yu¯ho¯ Kirchner present edition of The Record of Linji. notes. Unique among translations of Buddhist texts, the footnotes to both an authoritative statement of Zen’s Chinese readings have been changed to basic standpoint and a central source of Pinyin and the translation itself has been the Kirchner edition contain numerous explanations of material for Zen koan practice. Scholars revised in line with subsequent research grammatical constructions. Translators of classical Chinese will study the text for its importance in under- by Iriya Yoshitaka and Yanagida Seizan, immediately recognize the Kirchner edition constitutes a standing both Zen thought and East Asian the scholars who advised Mrs. Sasaki. -

Empty Cloud, the Autobiography of the Chinese Zen Master Xu

EMPTY CLOUD The Autobiography of the Chinese Zen Master XU YUN TRANSLATED BY CHARLES LUK Revised and Edited by Richard Hunn The Timeless Mind . Undated picture of Xu-yun. Empty Cloud 2 CONTENTS Contents .......................................................................................... 3 Acknowledgements ......................................................................... 4 Introduction .................................................................................... 5 CHAPTER ONE: Early Years ............................................................ 20 CHAPTER TWO: Pilgrimage to Mount Wu-Tai .............................. 35 CHAPTER THREE: The Journey West ............................................. 51 CHAPTER FOUR: Enlightenment and Atonement ......................... 63 CHAPTER FIVE: Interrupted Seclusion .......................................... 75 CHAPTER SIX: Taking the Tripitaka to Ji Zu Shan .......................... 94 CHAPTER SEVEN: Family News ................................................... 113 CHAPTER EIGHT: The Peacemaker .............................................. 122 CHAPTER NINE: The Jade Buddha ............................................... 130 CHAPTER TEN: Abbot At Yun-Xi and Gu-Shan............................. 146 CHAPTER ELEVEN: Nan-Hua Monastery ..................................... 161 CHAPTER TWELVE: Yun-Men Monastery .................................... 180 CHAPTER THIRTEEN: Two Discourses ......................................... 197 CHAPTER FOURTEEN: At the Yo Fo & Zhen Ru Monasteries -

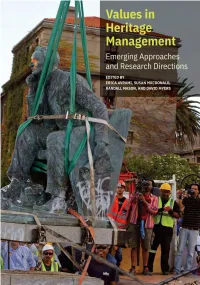

Values in Heritage Management

Values in Heritage Management Values in Heritage Management Emerging Approaches and Research Directions Edited by Erica Avrami, Susan Macdonald, Randall Mason, and David Myers THE GETTY CONSERVATION INSTITUTE, LOS ANGELES The Getty Conservation Institute Timothy P. Whalen, John E. and Louise Bryson Director Jeanne Marie Teutonico, Associate Director, Programs The Getty Conservation Institute (GCI) works internationally to advance conservation practice in the visual arts—broadly interpreted to include objects, collections, architecture, and sites. The Institute serves the conservation community through scientific research, education and training, field projects, and the dissemination of information. In all its endeavors, the GCI creates and delivers knowledge that contributes to the conservation of the world’s cultural heritage. © 2019 J. Paul Getty Trust Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Values in heritage management (2017 : Getty Conservation Institute), author. | Avrami, Erica C., editor. | Getty Conservation Institute, The text of this work is licensed under a Creative issuing body, host institution, organizer. Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- Title: Values in heritage management : emerging NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a approaches and research directions / edited by copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons Erica Avrami, Susan Macdonald, Randall .org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. All images are Mason, and David Myers. reproduced with the permission of the rights Description: Los Angeles, California : The Getty holders acknowledged in captions and are Conservation Institute, [2019] | Includes expressly excluded from the CC BY-NC-ND license bibliographical references. covering the rest of this publication. These images Identifiers: LCCN 2019011992 (print) | LCCN may not be reproduced, copied, transmitted, or 2019013650 (ebook) | ISBN 9781606066201 manipulated without consent from the owners, (epub) | ISBN 9781606066188 (pbk.) who reserve all rights. -

1 Course Description Course Delivery

IDS 2935 (1IKA, 1IK1) SELF AND SOCIETY IN EAST ASIA UF Quest 1/ Identity General Education: Humanities, International, Writing (2000) [Note: A minimum grade of C is required for General Education credit] Spring 2021, M/W/F 5th period (11:45am-12:35pm) MAT 0107 Instructors Teaching Assistant Stephan N. Kory, Assistant Prof. of Chinese Antara, Athmane, PhD Student [email protected] 392-7083 [email protected] Office Hours: W/F 3:00 to 4:00, or by appointment Office Hours: T/R 1.00 to 2.00, or by appointment Matthieu Felt, Assistant Prof. of Japanese [email protected] 273-3778 Office Hours: T/R 3:00 to 4:00, or by appointment Please email for an appointment, even within posted office hours. Course Description This interdisciplinary Quest 1 course prompts students to reconsider the nature of identities, both personal and social, as well as personhood itself, through a rigorous examination of traditional Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese texts. Much like the Bible or the US Constitution in America, these historical works inform mainstream cultural identity and practice in contemporary East Asia, despite their ancient provenance. Direct engagement with these primary sources will allow students to approach identity from a non-liberal perspective that does not revolve around ideas of inherent rights, freedoms, and liberties, and expose them to alternative ideas about the definition of humanity, the construction of society, and the so- called natural order. As a result, students will be able to critically reflect, through comparison, on the processes that create and maintain identities in our contemporary society, in the contemporary Asian present, and in the premodern Asian past.