The End of Punk: Joe Carducci Interviewed Kevin Mccaighy , May

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SST Defies Industry, Defines New Music

Page 1 The San Diego Union-Tribune October 1, 1995 Sunday SST Defies Industry, Defines New Music By Daniel de Vise KNIGHT-RIDDER NEWSPAPERS DATELINE: LOS ALAMITOS, CALIF. Ten years ago, when SST Records spun at the creative center of rock music, founder Greg Ginn was living with six other people in a one-room rehearsal studio. SST music was whipping like a sonic cyclone through every college campus in the country. SST bands criss-crossed the nation, luring young people away from arenas and corporate rock like no other force since the dawn of punk. But Greg Ginn had no shower and no car. He lived on a few thousand dollars a year, and relied on public transportation. "The reality is not only different, it's extremely, shockingly different than what people imagine," Ginn said. "We basically had one place where we rehearsed and lived and worked." SST, based in the Los Angeles suburb of Los Alamitos, is the quintessential in- dependent record label. For 17 years it has existed squarely outside the corporate rock industry, releasing music and spoken-word performances by artists who are not much interested in making money. When an SST band grows restless for earnings or for broader success, it simply leaves the label. Founded in 1978 in Hermosa Beach, Calif., SST Records has arguably produced more great rock bands than any other label of its era. Black Flag, fast, loud and socially aware, was probably the world's first hardcore punk band. Sonic Youth, a blend of white noise and pop, is a contender for best alternative-rock band ever. -

Boo-Hooray Catalog #10: Flyers

Catalog 10 Flyers + Boo-hooray May 2021 22 eldridge boo-hooray.com New york ny Boo-Hooray Catalog #10: Flyers Boo-Hooray is proud to present our tenth antiquarian catalog, exploring the ephemeral nature of the flyer. We love marginal scraps of paper that become important artifacts of historical import decades later. In this catalog of flyers, we celebrate phenomenal throwaway pieces of paper in music, art, poetry, film, and activism. Readers will find rare flyers for underground films by Kenneth Anger, Jack Smith, and Andy Warhol; incredible early hip-hop flyers designed by Buddy Esquire and others; and punk artifacts of Crass, the Sex Pistols, the Clash, and the underground Austin scene. Also included are scarce protest flyers and examples of mutual aid in the 20th Century, such as a flyer from Angela Davis speaking in Harlem only months after being found not guilty for the kidnapping and murder of a judge, and a remarkably illustrated flyer from a free nursery in the Lower East Side. For over a decade, Boo-Hooray has been committed to the organization, stabilization, and preservation of cultural narratives through archival placement. Today, we continue and expand our mission through the sale of individual items and smaller collections. We encourage visitors to browse our extensive inventory of rare books, ephemera, archives and collections and look forward to inviting you back to our gallery in Manhattan’s Chinatown. Catalog prepared by Evan Neuhausen, Archivist & Rare Book Cataloger and Daylon Orr, Executive Director & Rare Book Specialist; with Beth Rudig, Director of Archives. Photography by Evan, Beth and Daylon. -

California Noise: Tinkering with Hardcore and Heavy Metal in Southern California Steve Waksman

ABSTRACT Tinkering has long figured prominently in the history of the electric guitar. During the late 1970s and early 1980s, two guitarists based in the burgeoning Southern California hard rock scene adapted technological tinkering to their musical endeavors. Edward Van Halen, lead guitarist for Van Halen, became the most celebrated rock guitar virtuoso of the 1980s, but was just as noted amongst guitar aficionados for his tinkering with the electric guitar, designing his own instruments out of the remains of guitars that he had dismembered in his own workshop. Greg Ginn, guitarist for Black Flag, ran his own amateur radio supply shop before forming the band, and named his noted independent record label, SST, after the solid state transistors that he used in his own tinkering. This paper explores the ways in which music-based tinkering played a part in the construction of virtuosity around the figure of Van Halen, and the definition of artistic ‘independence’ for the more confrontational Black Flag. It further posits that tinkering in popular music cuts across musical genres, and joins music to broader cultural currents around technology, such as technological enthusiasm, the do-it-yourself (DIY) ethos, and the use of technology for the purposes of fortifying masculinity. Keywords do-it-yourself, electric guitar, masculinity, popular music, technology, sound California Noise: Tinkering with Hardcore and Heavy Metal in Southern California Steve Waksman Tinkering has long been a part of the history of the electric guitar. Indeed, much of the work of electric guitar design, from refinements in body shape to alterations in electronics, could be loosely classified as tinkering. -

COMING out on SEPTEMBER 11, 2015 New Releases from KALASHNIKOV COLLECTIVE BUSTER BROWN DARRELL BANKS REDD KROSS the JUKEBOX ROMANTICS

COMING OUT ON SEPTEMBER 11, 2015 new releases from KALASHNIKOV COLLECTIVE BUSTER BROWN DARRELL BANKS REDD KROSS THE JUKEBOX ROMANTICS Exclusively Distributed by KALASHNIKOV COLLECTIVE L’Algebra Morente Del Cielo, LP STREET DATE: September 11, 2015 INFORMATION: Artist Hometown: Milan, Italy Key Markets: Italy, Germany, France, Austria, Belgium, Netherlands, Spain, Portugal, Canada, Russia, USA For Fans of: CRASS, CONTROPOTERE, UK SUBS, LA FRACTION, WORLD/INFERNO FRIENDSHIP SOCIETY, THE CLASH, WRETCHED, RAW POWER, NEGAZIONE, DECLINO L’Algebra Morente Del Cielo (The Dying Algebra of the Sky in English) is the sixth full-length release from KALASHNIKOV COLLECTIVE, a seven- sometimes eight-piece romantic punk group from Milano, Italy. Since their inception in 1996, KALASHNIKOV has been renowned for their frenetic live performances, ARTIST: KALASHNIKOV COLLECTIVE groundbreaking songwriting, and sincere dedication to the DIY spirit of punk. Defying easy classification, TITLE: L’Algebra Morente Del Cielo the band embraces a myriad of musical and cultural influences; imagine an ‘80s crossover punk band doing LABEL: Aborted Society the tango to synthesizers, and you’re somewhat close. Coining the term “Romantic Punk,” KALASHNIKOV CAT#: ABSOC033-1 may have altogether invented a new genre of music, and have fast become one of the most innovative FORMAT: LP and important bands in the punk underground worldwide. New wave, ska, metal, thrash, anarchopunk, GENRE: Punk traditional and classical interludes weave in and out at a breakneck pace, and somehow make perfect BOX LOT: 25 sense in the world of KALASHNIKOV. It is a lyrical protest against an impending dystopian future, and if SRLP: $13.98 the revolution were to throw a dance party, this would be the soundtrack. -

Here Is a Printable

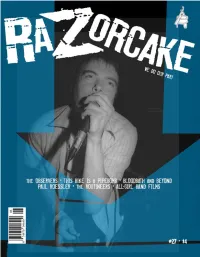

Ryan Leach is a skateboarder who grew up in Los Angeles and Ventura County. Like Belinda Carlisle and Lorna Doom, he graduated from Newbury Park High School. With Mor Fleisher-Leach he runs Spacecase Records. Leach’s interviews are available at Bored Out (http://boredout305.tumblr.com/). Razorcake is a bi-monthly, Los Angeles-based fanzine that provides consistent coverage of do-it-yourself punk culture. We believe in positive, progressive, community-friendly DIY punk, and are the only bona fide 501(c)(3) non-profit music magazine in America. We do our part. An Oral History of The Gun Club originally appeared in Razorcake #29, released in December 2005/January 2006. Original artwork and layout by Todd Taylor. Photos by Edward Colver, Gary Leonard and Romi Mori. Cover photo by Edward Colver. Zine design by Marcos Siref. Printing courtesy of Razorcake Press, Razorcake.org he Gun Club is one of Los Angeles’s greatest bands. Lead singer, guitarist, and figurehead Jeffrey Lee Pierce fits in easily with Tthe genius songwriting of Arthur Lee (Love), Chris Hillman (Byrds), and John Doe and Exene (X). Unfortunately, neither he nor his band achieved the notoriety of his fellow luminary Angelinos. From 1979 to 1996, Jeffrey manned the Gun Club ship through thick and mostly thin. Understandably, the initial Fire of Love and Miami lineup of Ward Dotson (guitar), Rob Ritter (bass), Jeffrey Lee Pierce (vocals/ guitar) and Terry Graham (drums) remains the most beloved; setting the spooky, blues-punk template for future Gun Club releases. At the time of its release, Fire of Love was heralded by East Coast critics as one of the best albums of 1981. -

Read Razorcake Issue #27 As A

t’s never been easy. On average, I put sixty to seventy hours a Yesterday, some of us had helped our friend Chris move, and before we week into Razorcake. Basically, our crew does something that’s moved his stereo, we played the Rhythm Chicken’s new 7”. In the paus- IInot supposed to happen. Our budget is tiny. We operate out of a es between furious Chicken overtures, a guy yelled, “Hooray!” We had small apartment with half of the front room and a bedroom converted adopted our battle call. into a full-time office. We all work our asses off. In the past ten years, That evening, a couple bottles of whiskey later, after great sets by I’ve learned how to fix computers, how to set up networks, how to trou- Giant Haystacks and the Abi Yoyos, after one of our crew projectile bleshoot software. Not because I want to, but because we don’t have the vomited with deft precision and another crewmember suffered a poten- money to hire anybody to do it for us. The stinky underbelly of DIY is tially broken collarbone, This Is My Fist! took to the six-inch stage at finding out that you’ve got to master mundane and difficult things when The Poison Apple in L.A. We yelled and danced so much that stiff peo- you least want to. ple with sourpusses on their faces slunk to the back. We incited under- Co-founder Sean Carswell and I went on a weeklong tour with our aged hipster dancing. -

Bad Rhetoric: Towards a Punk Rock Pedagogy Michael Utley Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 8-2012 Bad Rhetoric: Towards A Punk Rock Pedagogy Michael Utley Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the Rhetoric and Composition Commons Recommended Citation Utley, Michael, "Bad Rhetoric: Towards A Punk Rock Pedagogy" (2012). All Theses. 1465. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/1465 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BAD RHETORIC: TOWARDS A PUNK ROCK PEDAGOGY A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Professional Communication by Michael M. Utley August 2012 Accepted by: Dr. Jan Rune Holmevik, Committee Chair Dr. Cynthia Haynes Dr. Scot Barnett TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction ..........................................................................................................................4 Theory ................................................................................................................................32 The Bad Brains: Rhetoric, Rage & Rastafarianism in Early 1980s Hardcore Punk ..........67 Rise Above: Black Flag and the Foundation of Punk Rock’s DIY Ethos .........................93 Conclusion .......................................................................................................................109 -

Victorgories Packet Packet by Victor Pavao

Victorgories Packet Packet by Victor Pavao 1. In this symphony’s final movement, the horns introduce a disjunct secondary theme beginning “dotted half C, quarter note low G, dotted half high E.” Violins and cellos play thirty-second notes in the A-flat minor, third variation in this symphony’s second movement. Leonard Bernstein’s debut lecture on the CBS program (*) Omnibus was an analysis of this symphony. This symphony’s first movement features an oboe cadenza near the recapitulation. This symphony’s third movement continues into the fourth without pause, and ends with a note-for-note copy of the overture from Cherubini’s Eliza, which includes repeated C major chords. For 10 points, name this symphony whose first movement opens with the “G G G long Eb” fate motif. ANSWER: Ludwig van Beethoven, Symphony No. 5 in C Minor (prompt on “fate”) 2. A character who stays at this location repeatedly mentions her “cup of stars” after hearing a young girl demand one in a country restaurant. Two sisters who lived at this location fought bitterly over some family heirlooms, an argument that resulted in a companion’s suicide. While staying in this location, a character wakes up in the middle of the night to climb a deteriorated iron stairway. Arthur uses a device called a planchette in this place, which was once owned by Hugh (*) Crain. Theodora finds her room and clothes splashed in blood in this building, which is also visited by guests like Luke Sanderson and Eleanor Vance, who were invited to stay by Dr. -

Cartographic Perspectives Information Society 1

Number 53, Winterjournal 2006 of the Northcartographic American Cartographic perspectives Information Society 1 cartographic perspectives Number 53, Winter 2006 in this issue Letter from the Editor INTRODUCTION Art and Mapping: An Introduction 4 Denis Cosgrove Dear Members of NACIS, FEATURED ARTICLES Welcome to CP53, the first issue of Map Art 5 Cartographic Perspectives in 2006. I Denis Wood plan to be brief with my column as there is plenty to read on the fol- Interpreting Map Art with a Perspective Learned from 15 lowing pages. This is an important J.M. Blaut issue on Art and Cartography that Dalia Varanka was spearheaded about a year ago by Denis Wood and John Krygier. Art-Machines, Body-Ovens and Map-Recipes: Entries for a 24 It’s importance lies in the fact that Psychogeographic Dictionary nothing like this has ever been kanarinka published in an academic journal. Ever. To punctuate it’s importance, Jake Barton’s Performance Maps: An Essay 41 let me share a view of one of the John Krygier reviewers of this volume: CARTOGRAPHIC TECHNIQUES …publish these articles. Nothing Cartographic Design on Maine’s Appalachian Trail 51 more, nothing less. Publish them. Michael Hermann and Eugene Carpentier III They are exciting. They are interest- ing: they stimulate thought! …They CARTOGRAPHIC COLLECTIONS are the first essays I’ve read (other Illinois Historical Aerial Photography Digital Archive Keeps 56 than exhibition catalogs) that actu- Growing ally try — and succeed — to come to Arlyn Booth and Tom Huber terms with the intersections of maps and art, that replace the old formula REVIEWS of maps in/as art, art in/as maps by Historical Atlas of Central America 58 Reviewed by Mary L. -

Support Local Music & Arts

Contents OCTOBER 2015 Vol. 18 # 8 THE GOODS 4 Le Beat: Who’s who and what’s happening locally 11 Rock ‘n’ Roll Moment of the month 12 11 Questions: Jan Peters 20 Calendar 32 Monthly Pin-Up: Moongrass 34 Tales from the Road: Minor Plains 35 Stuff Yer Face: Hotpoint Tea & Express SPOTLIGHTS 6 Scotty Sensei: New dimensions 7 Panda Panda Panda: 1, 2, 3, GO 8 Zion I: The resurgence 9 Crushed out: Music and marriage FEATURES 14 Katie Johnson: The face of expression 15 I Found My Friends: The Oral History of Nirvana 16 Mark Pickerel and His Helping Hands: Still screaming 18 Beats Antique: Melding performance, music and art REVIEWS NEXT ISSUE: NOV. 2015 10 Live Shows DEADLINE: Oct. 19 25 Recordings 360.398.1155 • P.O. Box 30373, Bellingham, WA 98228 www.whatsup-magazine.com • [email protected] CO-PUBLISHER/EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Brent Cole CO-PUBLISHER/DESIGN DIRECTOR: Becca Schwarz Cole CONTRIBUTING WRITERS: Tommy Calderon, Jared Curtis, Thea Hart, Adam Walker, Mark Broyles, Jackson Main, Hayden Eller, Charlie Walentiny, Halee Hastad, Keenan Ketzner, Raleigh Davis, Aaron Apple, Aaron Kayser CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS: Tommy Calderon, David Johnson, Sarah Day, Ryan Russell, Aaron Brick AD SALES: Brent Cole, Victor Gotelaere DISTRIBUTION: David Johnson, Brent Cole COVER ARTIST: Katie Johnson WEB GENIUS: Django @ Seatthole SUPPORT: Harrison, Ruby, Autumn, Lulu What’s Up! is a free, independent monthly music magazine covering the Bellingham/Whatcom County scene, and is locally owned and operated by Brent Cole and Becca Schwarz Cole. What’s Up! is a member of Sustainable Connections, and a sister publication of Grow Northwest. -

American Foreign Policy, the Recording Industry, and Punk Rock in the Cold War

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University History Dissertations Department of History Spring 5-10-2017 Music for the International Masses: American Foreign Policy, The Recording Industry, and Punk Rock in the Cold War Mindy Clegg Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_diss Recommended Citation Clegg, Mindy, "Music for the International Masses: American Foreign Policy, The Recording Industry, and Punk Rock in the Cold War." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2017. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_diss/58 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MUSIC FOR THE INTERNATIONAL MASSES: AMERICAN FOREIGN POLICY, THE RECORDING INDUSTRY, AND PUNK ROCK IN THE COLD WAR by MINDY CLEGG Under the Direction of ALEX SAYF CUMMINGS, PhD ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the connections between US foreign policy initiatives, the global expansion of the American recording industry, and the rise of punk in the 1970s and 1980s. The material support of the US government contributed to the globalization of the recording industry and functioned as a facet American-style consumerism. As American culture spread, so did questions about the Cold War and consumerism. As young people began to question the Cold War order they still consumed American mass culture as a way of rebelling against the establishment. But corporations complicit in the Cold War produced this mass culture. Punks embraced cultural rebellion like hippies. -

Wavelength Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO Wavelength Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies 2-1986 Wavelength (February 1986) Connie Atkinson University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength Recommended Citation Wavelength (February 1986) 64 https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength/56 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies at ScholarWorks@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wavelength by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSI COS50 12/31199 BULK RATE EARL KLON6 LIBRARY tnL U. S. POSTAGE UNIV OF N.O. PAID ACQUISITIONS DEPT I N.O., LA 70148 ·VV39 Lt} COL. VIITDANS AT DAVID MON. -THUR. 1o-1 0 FRI. & SAT. 10-11 SUN. NOON-9 885-4200 Movies, Music & More! METAIRIE NEWORLEANS ¢1NEW LOCATIONJ VETmiANS ..,.~ sT. AT ocTAVIA formerly Leisure Landing 1 BL EAST OF CAUSEMY MON.-SAT. 1o-10 • MON.-SAT. 1o-10 SUN. NOON-8 SUN. NOON-9 88t-4028 834-8550 f) I ISSUE NO. 64 • FEBRUARY 1986 w/m not sure. but I'm almost positive. thai all music came from New Orleans.·· Ernie K-Doe. 1979 Features Flambeaux! ...................... 18 Slidell Blues . ......... ............ 20 James Booker . .................... 23 Departments February News . 4 Caribbean . 6 New Bands ....................... 8 U.S. Indies . ...................... 10 Rock ............................ 12 16-track Master Recorder: Movies .......................... 15 Reviews ........ ................ 17 Fostex B-16 February Listings ................. 25 Classifieds ....................... 29 Last Page . ....................... 30 COVER ART BY SKIP BOLEN Two #l hits in October. Member of NetWOfk Next? Puhlhhu. 'aun1an S S.ullt f..ditc•r .