BAM - a Journey from Nowhere to Nowhere by Jelle Brandt Corstius

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Results in I and II Cycles of the Internet Music Competition 2014

Results in I and II cycles of the Internet Music Competition 2014 I cycle: Duo, chamber ensemble, piano ensemble, choir, orchestra, percussion II cycle: Piano, bassoon, flute, french horn, clarinet, oboe, saxophone, trombone, trumpet, tube Internet Music Competition which passes completely through the Internet and it is unique event since its inception. In first and second cycles of the contest in 2014, was attended by 914 contestants from 22 countries and 198 cities from 272 schools: I cycle: "Duo" – 56 contestants "Piano Ensemble" – 94 contestants "Chamber Ensemble" – 73 contestants "Choir" – 23 contestants "Orchestra" – 28 contestant "Percussion "– 13 contestants. II cycle: "Piano" – 469 contestants "Bassoon" – 7 contestants "Flute" – 82 contestants "French horn" – 3 contestants "Clarinet" – 17 contestants "Oboe" – 8 contestants "Saxophone" – 27 contestants "Trombone" – 2 contestants "Trumpet" – 9 contestants "Tube" – 3 contestants The jury was attended by 37 musicians from 13 countries, many of whom are eminent teachers, musicians and artists who teach at prestigious music institutions are soloists and play in the top 10 best orchestras and opera houses. The winners of the first cycle in Masters Final Internet Music Competition 2014: "Duo" – Djamshid Saidkarimov, Pak Artyom (Tashkent, Uzbekistan) "Piano Ensemble" – Koval Ilya, Koval Yelissey (Karaganda, Kazakhstan) "Chamber Ensemble" – Creative Quintet (Sanok, Poland) "Choir" – Womens Choir Ave musiсa HGEU (Odessa, Ukraine) "Orchestra" – “Victoria” (Samara, Russia) "Percussion" – -

A Region with Special Needs the Russian Far East in Moscow’S Policy

65 A REGION WITH SPECIAL NEEDS THE RUSSIAN FAR EAST IN MOSCOW’s pOLICY Szymon Kardaś, additional research by: Ewa Fischer NUMBER 65 WARSAW JUNE 2017 A REGION WITH SPECIAL NEEDS THE RUSSIAN FAR EAST IN MOSCOW’S POLICY Szymon Kardaś, additional research by: Ewa Fischer © Copyright by Ośrodek Studiów Wschodnich im. Marka Karpia / Centre for Eastern Studies CONTENT EDITOR Adam Eberhardt, Marek Menkiszak EDITOR Katarzyna Kazimierska CO-OPERATION Halina Kowalczyk, Anna Łabuszewska TRANSLATION Ilona Duchnowicz CO-OPERATION Timothy Harrell GRAPHIC DESIGN PARA-BUCH PHOTOgrAPH ON COVER Mikhail Varentsov, Shutterstock.com DTP GroupMedia MAPS Wojciech Mańkowski PUBLISHER Ośrodek Studiów Wschodnich im. Marka Karpia Centre for Eastern Studies ul. Koszykowa 6a, Warsaw, Poland Phone + 48 /22/ 525 80 00 Fax: + 48 /22/ 525 80 40 osw.waw.pl ISBN 978-83-65827-06-7 Contents THESES /5 INTRODUctiON /7 I. THE SPEciAL CHARActERISticS OF THE RUSSIAN FAR EAST AND THE EVOLUtiON OF THE CONCEPT FOR itS DEVELOPMENT /8 1. General characteristics of the Russian Far East /8 2. The Russian Far East: foreign trade /12 3. The evolution of the Russian Far East development concept /15 3.1. The Soviet period /15 3.2. The 1990s /16 3.3. The rule of Vladimir Putin /16 3.4. The Territories of Advanced Development /20 II. ENERGY AND TRANSPORT: ‘THE FLYWHEELS’ OF THE FAR EAST’S DEVELOPMENT /26 1. The energy sector /26 1.1. The resource potential /26 1.2. The infrastructure /30 2. Transport /33 2.1. Railroad transport /33 2.2. Maritime transport /34 2.3. Road transport /35 2.4. -

Subject of the Russian Federation)

How to use the Atlas The Atlas has two map sections The Main Section shows the location of Russia’s intact forest landscapes. The Thematic Section shows their tree species composition in two different ways. The legend is placed at the beginning of each set of maps. If you are looking for an area near a town or village Go to the Index on page 153 and find the alphabetical list of settlements by English name. The Cyrillic name is also given along with the map page number and coordinates (latitude and longitude) where it can be found. Capitals of regions and districts (raiony) are listed along with many other settlements, but only in the vicinity of intact forest landscapes. The reader should not expect to see a city like Moscow listed. Villages that are insufficiently known or very small are not listed and appear on the map only as nameless dots. If you are looking for an administrative region Go to the Index on page 185 and find the list of administrative regions. The numbers refer to the map on the inside back cover. Having found the region on this map, the reader will know which index map to use to search further. If you are looking for the big picture Go to the overview map on page 35. This map shows all of Russia’s Intact Forest Landscapes, along with the borders and Roman numerals of the five index maps. If you are looking for a certain part of Russia Find the appropriate index map. These show the borders of the detailed maps for different parts of the country. -

The Bratsk-Ilimsk Territorial Production Complex: a Field Study Report

THE BRATSK-ILIMSK TERRITORIAL PRODUCTION COMPLEX: A FIELD STUDY REPORT H. Knop and A. Straszak, Editore RR-78-2 May 1978 Research Reports provide the formal record of research conducted by the International lnstitute for Applied Systems Analysis. They are carefully reviewed before publication and represent, in the Institute's best judgment, competent scientific work. Views or opinions expressed therein, however, do not necessarily reflect those of the National Member Organizations supporting the lnstitute or of the lnstitute itself. International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis A-236 1 Laxenburg, Austria Copyright @ 1978 IIASA AU ' hts reserved. No part of this publication may be repro7 uced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publieher. Preface The Management and Technology Area of IIASA has carried out case studies of large-scale development programs since 1975. The purpose of these studies is to examine successful programs of regional development from an international perspective, with a multidisciplinary team of scientists skilled in the use of systems analysis. The study of the Bratsk-Ilimsk Territorial Production Complex (BITPC) represents an interim effort in our research activities. The first study was of the Tennessee Valley Authority in the United States*, forthcoming is the study of the Shinkansen development program in Japan. The present Report covers six major aspects of the BITPC program: goals, variants, and strategies; planning and organization; model calculations and computer applications; integration of environmental factors; energy supply systems; and water resources. It is hoped that the experience of the Soviet scientists and practitioners and the observations and suggestions of the study team will ~rovidethe IIASA National Member Organizations" with insights into problem solving in the management, planning, and organization of large-scale development programs. -

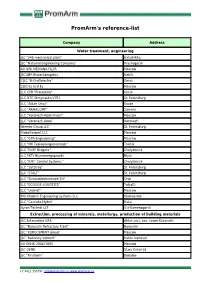

Promarm's Reference-List

PromArm's reference-list Company Address Water treatment, engineering JSC "345 mechanical plant" Balashikha JSC "National Engineering Company" Krasnogorsk AO NPK MEDIANA-FILTR Moscow JSC NPP Biotechprogress Kirishi CJSC "B-Graffelectro" Omsk CJSC Es End Ey Moscow LLC CPB "Protection" Omsk LLC NTC Stroynauka-VITU St. Petersburg LLC "Aidan Stroy" Kazan LLC "ARMACOMP" Samara LLC "Voronezh-Aqua Invest" Moscow LLC "Voronezh-Aqua" Voronezh Hermes Group LLC St. Petersburg Globaltexport LLC Moscow LLC "GPA Engineering" Moscow LLC "MK Teploenergomontazh" Troitsk LLC "NVK" Niagara " Chelyabinsk LLC PKTs Biyskenergoproekt Biysk LLC "RPK" Control Systems " Chelyabinsk LLC "SetStroy" St. Petersburg LLC "STALT" St. Petersburg LLC "Stroisantechservice-1N" Orsk LLC "ECOLINE-LOGISTICS" Tolyatti LLC "Unimet" Moscow PKK Modern Engineering Systems LLC Vladivostok LLC "Cascade-Hydro" Baku Ayron-Technik LLP Ust-Kamenogorsk Extraction, processing of minerals, metallurgy, production of building materials JSC Aldanzoloto GRK Aldan ulus, pos. Lower Kuranakh JSC "Borovichi Refractory Plant" Borovichi JSC "EUROCEMENT group" Moscow JSC "Katavsky cement" Katav-Ivanovsk AO OKHK URALCHEM Moscow JSC OEMK Stary Oskol-15 JSC "Firstborn" Bodaibo +7 8412 350797, [email protected], www.promarm.ru JSC "Aleksandrovsky Mine" Mogochinsky district of Davenda JSC RUSAL Ural Kamensk-Uralsky JSC "SUAL" Kamensk-Uralsky JSC "Khiagda" Bounty district, with. Bagdarin JSC "RUSAL Sayanogorsk" Sayanogorsk CJSC "Karabashmed" Karabash CJSC "Liskinsky gas silicate" Voronezh CJSC "Mansurovsky career management" Istra district, Alekseevka village Mineralintech CJSC Norilsk JSC "Oskolcement" Stary Oskol CJSC RCI Podolsk Refractories Shcherbinka Bonolit OJSC - Construction Solutions Old Kupavna LLC "AGMK" Amursk LLC "Borgazobeton" Boron Volga Cement LLC Nizhny Novgorod LLC "VOLMA-Absalyamovo" Yutazinsky district, with. Absalyamovo LLC "VOLMA-Orenburg" Belyaevsky district, pos. -

A Case Study on the Angara/Yenisey River System in the Siberian Region

land Article Optical Spectral Tools for Diagnosing Water Media Quality: A Case Study on the Angara/Yenisey River System in the Siberian Region Costas A. Varotsos 1,2 , Vladimir F. Krapivin 3, Ferdenant A. Mkrtchyan 3 and Yong Xue 2,4,* 1 Department of Environmental Physics and Meteorology, University of Athens, 15784 Athens, Greece; [email protected] 2 School of Environment Science and Geoinformatics, China University of Mining and Technology, Xuzhou 221116, China 3 Kotelnikov Institute of Radioengineering and Electronics, Fryazino Branch, Russian Academy of Sciences, Fryazino, 141190 Moscow, Russia; [email protected] (V.F.K.); [email protected] (F.A.M.) 4 College of Science and Engineering, University of Derby, Derby DD22 3AW, UK * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: This paper presents the results of spectral optical measurements of hydrochemical char- acteristics in the Angara/Yenisei river system (AYRS) extending from Lake Baikal to the estuary of the Yenisei River. For the first time, such large-scale observations were made as part of a joint American-Russian expedition in July and August of 1995, when concentrations of radionuclides, heavy metals, and oil hydrocarbons were assessed. The results of this study were obtained as part of the Russian hydrochemical expedition in July and August, 2019. For in situ measurements and sampling at 14 sampling sites, three optical spectral instruments and appropriate software were used, including big data processing algorithms and an AYRS simulation model. The results show Citation: Varotsos, C.A.; Krapivin, V.F.; Mkrtchyan, F.A.; Xue, Y. Optical that the water quality in AYRS has improved slightly due to the reasonably reduced anthropogenic Spectral Tools for Diagnosing Water industrial impact. -

Bulletin of the Geological Society of Greece

Bulletin of the Geological Society of Greece Vol. 43, 2010 THE ANTHROPOGENIC CHANGES IN THE GEOLOGICAL ENVIRONMENT IN THE SOUTH OF EAST SIBERIA Kozyreva E.A Institute of the Earth’s Crust Russian Academy of Sciences Siberian Branch, Laboratory of engineering geology and geoecology Khak V.A. Institute of the Earth’s Crust Russian Academy of Sciences Siberian Branch, Laboratory of engineering geology and geoecology https://doi.org/10.12681/bgsg.11294 Copyright © 2017 E.A Kozyreva, V.A. Khak To cite this article: Kozyreva, E., & Khak, V. (2010). THE ANTHROPOGENIC CHANGES IN THE GEOLOGICAL ENVIRONMENT IN THE SOUTH OF EAST SIBERIA. Bulletin of the Geological Society of Greece, 43(3), 1192-1201. doi:https://doi.org/10.12681/bgsg.11294 http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 20/02/2020 21:49:42 | Δελτίο της Ελληνικής Γεωλογικής Εταιρίας, 2010 Bulletin of the Geological Society of Greece, 2010 Πρακτικά 12ου Διεθνούς Συνεδρίου Proceedings of the 12th International Congress Πάτρα, Μάιος 2010 Patras, May, 2010 THE ANTHROPOGENIC CHANGES IN THE GEOLOGICAL ENVIRONMENT IN THE SOUTH OF EAST SIBERIA Kozyreva E.A., Khak V.A. Institute of the Earth’s Crust Russian Academy of Sciences Siberian Branch, Laboratory of engineering ge- ology and geoecology, Lermontov Street 128, 664033 Irkutsk, Russia, [email protected], [email protected] Abstract The investigation results of the geological environment’s condition in an areas marked by high an- thropogenic load are described in this paper. In the southern East Siberia the strategy of key sites monitoring is used for this purpose. The selection of key sites is determined by the specific charac- ter of geological environment, as well as by the intensity and relationships of developing geologi- cal processes. -

Pcbs and Ocps in Human Milk in Eastern Siberia, Russia: Levels, Temporal Trends and Infant Exposure Assessment

Chemosphere 178 (2017) 239e248 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Chemosphere journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/chemosphere PCBs and OCPs in human milk in Eastern Siberia, Russia: Levels, temporal trends and infant exposure assessment * Elena A. Mamontova , Eugenia N. Tarasova, Alexander A. Mamontov Vinogradov Institute of Geochemistry, Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 664033, Favorsky Str., 1A, PO Box 421, Irkutsk, Russia highlights graphical abstract PCBs and OCPs were quantified in 155 human milk samples from Eastern Siberia. Highly exposed to PCB and DDT group have been identified in Eastern Siberia. Fat and meat of freshwater seal could be sources of the POP exposure of humans. Location of food production can in- fluence on POP levels in HM in industrialized areas. OCP levels in human milk show de- creases between 1980 and 2000s. article info abstract Article history: The aim of our study is to investigate the spatial distribution of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), hex- Received 28 September 2016 achlorobenzene (HCB), dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (p,p0-DDT) and its metabolites, a- and g-isomers Received in revised form of hexachlorocyclohexane (HCH) in 155 samples of human milk (HM) from Eastern Siberia (six towns and 21 February 2017 seven villages in Irkutsk Region, one village of the Republic of Buryatia and one town in Zabaikal'sk Accepted 13 March 2017 Region, Russia), and to examine the dietary and social factors influencing the human exposure to the organochlorines. The median and range of the concentration of six indicator PCBs in HM in 14 localities À Handling Editor: Andreas Sjodin in Eastern Siberia (114 (19e655) ng g 1 lipids respectively) are similar to levels in the majority of Eu- ropean countries. -

Publishable Final Activity Report Revision 1

INCO-CT2006-015110 IRIS Final Activity Report INCO-CT2006-015110 www.iris.uni-jena.de Instrument: Specific Support Action Thematic Priority:Environmental Protection Publishable Final Activity Report Revision 1 Period covered: 01. July 2006 - 31. October 2008 Date of Preparation: 31.01.09 Organisation name of lead contractor for this deliverable: Friedrich-Schiller-University Jena (FSU) Project co-funded by the European Commission within the 6th Framework Programme (2002-2006) Dissemination Level PU Public PU PP Restricted to other programme participants (including the Commission Services) RE Restricted to a group specified by the consortium (including the Commission Services) CO Confidential, only for members of the consortium (including the Commission Services) 1 INCO-CT2006-015110 IRIS Final Activity Report Table of Contents Project Execution.............................................................................................................................. 7 1. Project Objectives..................................................................................................................... 7 1.1. The Irkutsk Region ..........................................................................................................7 2. The Consortium........................................................................................................................ 9 3. Work Performance................................................................................................................. 11 3.1. State-of-the-Art..............................................................................................................11 -

RUSSIAN DISTRICTS AWARD LIST" (Last Update 01.07.2012)

"RUSSIAN DISTRICTS AWARD LIST" (Last update 01.07.2012) Republic of Adygeya (AD) UA6Y CITIES AD-01 MAIKOP AD-02 ADYGEJSK AREAS AD-03 GIAGINSKY AREA AD-04 KOSHEHABL'SKY AREA AD-05 KRASNOGVARDEJSKY AREA AD-06 MAJKOPSKY AREA AD-07 TAHTAMUKAJSKY AREA AD-08 TEUCHEZHSKY AREA AD-09 SHOVGENOVSKY AREA Altaysky Kraj (AL) UA9Y BARNAUL AREAS AL-01 ZHELEZNODOROZHNY AL-02 INDUSTRIALNY AL-03 LENINSKY AL-04 OKTJABR`SKY AL-05 CENTRALNY CITIES AL-06 deleted AL-07 deleted AL-08 RUBTSOVSK AL-09 SLAVGOROD AL-10 YAROVOE AREAS AL-11 ALEJSKY AREA AL-12 ALTAYSKY AREA AL-13 BAEVSKY AREA AL-14 BIJSKY AREA AL-15 BLAGOVESHCHENSKY AREA AL-16 BURLINSKY AREA AL-17 BYSTROISTOKSKY AREA AL-18 VOLCHIHINSKY AREA AL-19 EGOR'EVSKY AREA AL-20 EL'TSOVSKY AREA AL-21 ZAV'JALOVSKY AREA AL-22 ZALESOVSKY AREA AL-23 ZARINSKY AREA AL-24 ZMEINOGORSKY AREA AL-25 ZONALNY AREA AL-26 KALMANSKY AREA AL-27 KAMENSKY AREA AL-28 KLJUCHEVSKY AREA AL-29 KOSIHINSKY AREA AL-30 KRASNOGORSKY AREA AL-31 KRASNOSHCHEKOVSKY AREA AL-32 KRUTIHINSKY AREA AL-33 KULUNDINSKY AREA AL-34 KUR'INSKY AREA AL-35 KYTMANOVSKY AREA AL-36 LOKTEVSKY AREA AL-37 MAMONTOVSKY AREA AL-38 MIHAJLOVSKY AREA AL-39 NEMETSKY NATIONAL AREA AL-40 NOVICHIHINSKY AREA AL-41 PAVLOVSKY AREA AL-42 PANKRUSHIHINSKY AREA AL-43 PERVOMAJSKY AREA AL-44 PETROPAVLOVSKY AREA AL-45 POSPELIHINSKY AREA AL-46 REBRIHINSKY AREA AL-47 RODINSKY AREA AL-48 ROMANOVSKY AREA AL-49 RUBTSOVSKY AREA AL-50 SLAVGORODSKY AREA AL-51 SMOLENSKY AREA AL-52 SOVIETSKY AREA AL-53 SOLONESHENSKY AREA AL-54 SOLTONSKY AREA AL-55 SUETSKY AREA AL-56 TABUNSKY AREA AL-57 TAL'MENSKY -

The East Siberia/Pacific Ocean (ESPO) Oil Pipeline: a Strategic Project – an Organisational Failure? N T a R Y M E Wojciech Konończuk C E S C O M

ces Commentary i s s u e 2 | 2 2 . 0 . 2 0 0 8 | c e ntr e f or e A s T e rn s T u d i e s The East Siberia/Pacific Ocean (ESPO) oil pipeline: a strategic project – an organisational failure? N T A R y M e Wojciech Konończuk c e s c O M The East Siberia/Pacific Ocean (ESPO) oil pipeline is currently the most important and expensive investment in the Russian energy sector. Although this Far Eastern pipeline is rarely mentioned in the European media, this t u d i e s is a strategic project for Russia and is far more significant than other s widely publicised energy projects such as the North Stream Pipeline. On one hand, the new oil pipeline is expected to trigger the development a s t e r n of oilfields in East Siberia, which is planned to become a key oil production e centre for Russia in the future, especially in the face of decreasing pro- duction volumes in western Siberia. This grand infrastructural project is thus expected to be a catalyst for development of the entire Far Eastern e n t r e f o r c region. On the other hand, the ESPO is intended to diversify Russian oil and gas exports by increasing Russia’s presence on Asian markets, so that Europe is no longer the monopolistic consumer of Russian energy reso- urces. Moreover, the ESPO construction’s unusually high costs seem to N T A R y suggest that economic reasons are not the only ones which have brought M e about the practical implementation of the project. -

Resolution # 784 of the Government of the Russian Federation Dated July

Resolution # 784 of the Government of the Russian Federation dated July 17, 1998 On the List of Joint-Stock Companies Producing Goods (Products, Services) of Strategic Importance for Safeguarding National Security of the State with Federally-Owned Shares Not to Be Sold Ahead of Schedule (Incorporates changes and additions of August 7, August 14, October 31, November 14, December 18, 1998; February 27, August 30, September 3, September 9, October 16, December 31, 1999; March 16, October 19, 2001; and May 15, 2002) In connection with the Federal Law “On Privatization of State Property and Fundamental Principles of Privatizing Municipal Property in the Russian Federation”, and in accordance with paragraph 1 of Decree # 478 of the President of the Russian Federation dated May 11, 1995 “On Measures to Guarantee the Accommodation of Privatization Revenues in thee Federal Budget” (Sobraniye Zakonodatelstva Rossiyskoy Federatsii, 1995, # 20, page 1776; 1996, # 39, page 4531; 1997, # 5, page 658; # 20, page 2240), the Government of the Russian Federation has resolved: 1. To adopt the List of Joint-Stock Companies Producing Goods (Products, Services) of Strategic Importance for Safeguarding National Security of the State with Federally-Owned Shares Not to Be Sold Ahead of Schedule (attached). In accordance with Decree # 1514 of the President of the Russian Federation dated December 21, 2001, pending the adoption by the President of the Russian Federation in concordance with Article 6 of the Federal Law “On Privatization of State and Municipal Property” of lists of strategic enterprises and strategic joint-stock companies, changes and additions to the list of joint-stock companies adopted by this Resolution shall bee introduced by Resolutions of the Government of the Russian Federation issued on the basis of Decrees of the President of the Russian Federation.