Big Bend National Park, Texas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redalyc.Preliminary Report on a Late Cretaceous Vertebrate Fossil

Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana ISSN: 1405-3322 [email protected] Sociedad Geológica Mexicana, A.C. México Rivera-Sylva, Héctor E.; Frey, Eberhard; Palomino-Sánchez, Francisco J.; Guzmán-Gutiérrez, José Rubén; Ortiz-Mendieta, Jorge A. Preliminary Report on a Late Cretaceous Vertebrate Fossil Assemblage in Northwestern Coahuila, Mexico Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana, vol. 61, núm. 2, 2009, pp. 239-244 Sociedad Geológica Mexicana, A.C. Distrito Federal, México Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=94316034014 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Preliminary Report on a Late Cretaceous Vertebrate Fossil Assemblage in Northwestern Coahuila, Mexico 239 BOLETÍN DE LA SOCIEDAD GEOLÓGICA MEXICANA VOLUMEN 61, NÚM. 2, 2009, P. 239-244 D GEOL DA Ó E G I I C C O A S 1904 M 2004 . C EX . ICANA A C i e n A ñ o s Preliminary Report on a Late Cretaceous Vertebrate Fossil Assemblage in Northwestern Coahuila, Mexico Héctor E. Rivera-Sylva1, Eberhard Frey2, Francisco J. Palomino-Sánchez3, José Rubén Guzmán-Gutiérrez4, Jorge A. Ortiz-Mendieta5 1 Departamento de Paleontología, Museo del Desierto. Pról. Pérez Treviño 3745, 25015, Saltillo, Coah., México. 2 Geowissenschaftliche Abteilung,Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde Karlsruhe. Karlsruhe, Alemania. 3 Laboratorio de Petrografía y Paleontología, Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática, Aguascalientes, Ags., México. 4 Centro para la Conservación del Patrimonio Natural y Cultural de México, Aguascalientes, Ags., México. -

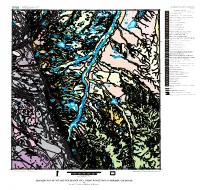

GEOLOGIC MAP of the GREATER DENVER AREA, FRONT RANGE URBAN CORRIDOR, COLORADO by Donald E

U.S DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR MISCELLANEOUS INVESTIGATIONS SERIES I–856–H U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Version 1.1 105°22'30" 105°15' 105°7'30" 105°0' 104°52'30" 104°45' 104°37'30" 40¡0’ 40°0' Qs Qv Ql Qes DESCRIPTION OF MAP UNITS Qco Qp Qlo Kp Qp Kp Kl Kl Qb TKda Ysp Qes Kf Qb Qp Qco Qv Xbc Kp Qb Qes Qp POST-PINEY CREEK AND PINEY CREEK ALLUVIUM (UPPER HOLOCENE) Kl Qes Qes Qco Qlo Qs Qlo Kp Kl Qb Qrf Qls Kf Ql Ysp TKd Qs Qco COLLUVIUM (UPPER HOLOCENE) Xbc Qp Qv Ysp Qp Qb Kl Qv Qes PPf Qp Qco Qco Qrf Kp Qs Qls Qs LANDSLIDE DEPOSITS (HOLOCENE TO MIDDLE? PLEISTOCENE) Qs Qv Kl Qb Qp JPml Kl Qrf Qco Qs Qco Qv Qp Qes WINDBLOWN SAND (LOWER HOLOCENE TO UPPER PLEISTOCENE) Qv Ql TKd Ql Qes Kd Qv Kp Kl Qes Qco River Qco Qp Kf Ql TKda YXp TKda Kl TKda TKd Qs Xbc Qrf Qv Qp Qb Qb BROADWAY ALLUVIUM (UPPER PLEISTOCENE) Qp Qco Qs Qco Qlo Qco Ql Qp Qes Kf Ql Qco Qp Qv Qs Qrf Ql LOESS (UPPER PLEISTOCENE) Qrf Qs Qlo Kf Qs Qco Qco Qp Qes Qp Qco Qp TKd Qb Qco Qlo Qes LOUVIERS ALLUVIUM (UPPER PLEISTOCENE) Xbc Kf Kp Ql Qs Qrf Marshall Qv Qb Ql Kl TKda Qes Qs Kl Lake Qv Qs SLOCUM ALLUVIUM (PLEISTOCENE) Qv Ql Qco JPml Ql Qco PPf Qv Qs Kl Qs Qco Qv Qco Kn Qv Qs Qs Kp Qrf Qb Qb Barr Lake Kcgg Qv VERDOS ALLUVIUM (PLEISTOCENE) Qs Qrf Qco Ql TKda Qlo Qp Qs TKda Qp Ql TKda Xqm Qlo Qrf Qs Qs Qs ROCKY FLATS ALLUVIUM (PLEISTOCENE) Qp Xq Kd Kf Qco Qp Qco Qb Kl Kp Qco Platte Qlo Qb Qrf Qs Qn Qls Qco NUSSBAUM ALLUVIUM (PLEISTOCENE) Kp Qco Qp Xbc TKd Qrf Qrf Qv Qco Tg Qv Qv HIGH-LEVEL GRAVEL DEPOSITS (PLIOCENE TO OLIGOCENE) Xbc Qp PPf Qb TKd Qb Qv TKda JPml Qv Ql Tcr CASTLE ROCK -

A New Microvertebrate Assemblage from the Mussentuchit

A new microvertebrate assemblage from the Mussentuchit Member, Cedar Mountain Formation: insights into the paleobiodiversity and paleobiogeography of early Late Cretaceous ecosystems in western North America Haviv M. Avrahami1,2,3, Terry A. Gates1, Andrew B. Heckert3, Peter J. Makovicky4 and Lindsay E. Zanno1,2 1 Department of Biological Sciences, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, USA 2 North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, Raleigh, NC, USA 3 Department of Geological and Environmental Sciences, Appalachian State University, Boone, NC, USA 4 Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, IL, USA ABSTRACT The vertebrate fauna of the Late Cretaceous Mussentuchit Member of the Cedar Mountain Formation has been studied for nearly three decades, yet the fossil-rich unit continues to produce new information about life in western North America approximately 97 million years ago. Here we report on the composition of the Cliffs of Insanity (COI) microvertebrate locality, a newly sampled site containing perhaps one of the densest concentrations of microvertebrate fossils yet discovered in the Mussentuchit Member. The COI locality preserves osteichthyan, lissamphibian, testudinatan, mesoeucrocodylian, dinosaurian, metatherian, and trace fossil remains and is among the most taxonomically rich microvertebrate localities in the Mussentuchit Submitted 30 May 2018 fi fi Accepted 8 October 2018 Member. To better re ne taxonomic identi cations of isolated theropod dinosaur Published 16 November 2018 teeth, we used quantitative analyses of taxonomically comprehensive databases of Corresponding authors theropod tooth measurements, adding new data on theropod tooth morphodiversity in Haviv M. Avrahami, this poorly understood interval. We further provide the first descriptions of [email protected] tyrannosauroid premaxillary teeth and document the earliest North American record of Lindsay E. -

Forgotten Crocodile from the Kirtland Formation, San Juan Basin, New

posed that the narial cavities of Para- Wima1l- saurolophuswere vocal resonating chambers' Goniopholiskirtlandicus Apparently included with this material shippedto Wiman was a partial skull that lromthe Wiman describedas a new speciesof croc- forgottencrocodile odile, Goniopholis kirtlandicus. Wiman publisheda descriptionof G. kirtlandicusin Basin, 1932in the Bulletin of the GeologicalInstitute KirtlandFormation, San Juan of IJppsala. Notice of this specieshas not appearedin any Americanpublication. Klilin NewMexico (1955)presented a descriptionand illustration of the speciesin French, but essentially repeatedWiman (1932). byDonald L. Wolberg, Vertebrate Paleontologist, NewMexico Bureau of lVlinesand Mineral Resources, Socorro, NIM Localityinformation for Crocodilian bone, armor, and teeth are Goni o p holi s kir t landicus common in Late Cretaceous and Early Ter- The skeletalmaterial referred to Gonio- tiary deposits of the San Juan Basin and pholis kirtlandicus includesmost of the right elsewhere.In the Fruitland and Kirtland For- side of a skull, a squamosalfragment, and a mations of the San Juan Basin, Late Creta- portion of dorsal plate. The referral of the ceous crocodiles were important carnivores of dorsalplate probably represents an interpreta- the reconstructed stream and stream-bank tion of the proximity of the material when community (Wolberg, 1980). In the Kirtland found. Figs. I and 2, taken from Wiman Formation, a mesosuchian crocodile, Gonio- (1932),illustrate this material. pholis kirtlandicus, discovered by Charles H. Wiman(1932, p. 181)recorded the follow- Sternbergin the early 1920'sand not described ing locality data, provided by Sternberg: until 1932 by Carl Wiman, has been all but of Crocodile.Kirtland shalesa 100feet ignored since its description and referral. "Skull below the Ojo Alamo Sandstonein the blue Specimensreferred to other crocodilian genera cley. -

CRETACEOUS-TERTIARY BOUNDARY Ijst the ROCKY MOUNTAIN REGION1

BULLETIN OF THE GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA V o l..¿5, pp. 325-340 September 15, 1914 PROCEEDINGS OF THE PALEONTOLOGICAL SOCIETY CRETACEOUS-TERTIARY BOUNDARY IjST THE ROCKY MOUNTAIN REGION1 BY P. H . KNOWLTON (Presented before the Paleontological Society December 31, 1913) CONTENTS Page Introduction........................................................................................................... 325 Stratigraphic evidence........................................................................................ 325 Paleobotanical evidence...................................................................................... 331 Diastrophic evidence........................................................................................... 334 The European time scale.................................................................................. 335 Vertebrate evidence............................................................................................ 337 Invertebrate evidence.......................................................................................... 339 Conclusions............................................................................................................ 340 I ntroduction The thesis of this paper is as follows: It is proposed to show that the dinosaur-bearing beds known as “Ceratops beds,” “Lance Creek bieds,” Lance formation, “Hell Creek beds,” “Somber beds,” “Lower Fort Union,”- Laramie of many writers, “Upper Laramie,” Arapahoe, Denver, Dawson, and their equivalents, are above a major -

A Phylogenomic Analysis of Turtles ⇑ Nicholas G

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 83 (2015) 250–257 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev A phylogenomic analysis of turtles ⇑ Nicholas G. Crawford a,b,1, James F. Parham c, ,1, Anna B. Sellas a, Brant C. Faircloth d, Travis C. Glenn e, Theodore J. Papenfuss f, James B. Henderson a, Madison H. Hansen a,g, W. Brian Simison a a Center for Comparative Genomics, California Academy of Sciences, 55 Music Concourse Drive, San Francisco, CA 94118, USA b Department of Genetics, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA c John D. Cooper Archaeological and Paleontological Center, Department of Geological Sciences, California State University, Fullerton, CA 92834, USA d Department of Biological Sciences, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA 70803, USA e Department of Environmental Health Science, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA f Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA g Mathematical and Computational Biology Department, Harvey Mudd College, 301 Platt Boulevard, Claremont, CA 9171, USA article info abstract Article history: Molecular analyses of turtle relationships have overturned prevailing morphological hypotheses and Received 11 July 2014 prompted the development of a new taxonomy. Here we provide the first genome-scale analysis of turtle Revised 16 October 2014 phylogeny. We sequenced 2381 ultraconserved element (UCE) loci representing a total of 1,718,154 bp of Accepted 28 October 2014 aligned sequence. Our sampling includes 32 turtle taxa representing all 14 recognized turtle families and Available online 4 November 2014 an additional six outgroups. Maximum likelihood, Bayesian, and species tree methods produce a single resolved phylogeny. -

Membros Da Comissão Julgadora Da Dissertação

UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO FACULDADE DE FILOSOFIA, CIÊNCIAS E LETRAS DE RIBEIRÃO PRETO PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM BIOLOGIA COMPARADA Evolution of the skull shape in extinct and extant turtles Evolução da forma do crânio em tartarugas extintas e viventes Guilherme Hermanson Souza Dissertação apresentada à Faculdade de Filosofia, Ciências e Letras de Ribeirão Preto da Universidade de São Paulo, como parte das exigências para obtenção do título de Mestre em Ciências, obtido no Programa de Pós- Graduação em Biologia Comparada Ribeirão Preto - SP 2021 UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO FACULDADE DE FILOSOFIA, CIÊNCIAS E LETRAS DE RIBEIRÃO PRETO PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM BIOLOGIA COMPARADA Evolution of the skull shape in extinct and extant turtles Evolução da forma do crânio em tartarugas extintas e viventes Guilherme Hermanson Souza Dissertação apresentada à Faculdade de Filosofia, Ciências e Letras de Ribeirão Preto da Universidade de São Paulo, como parte das exigências para obtenção do título de Mestre em Ciências, obtido no Programa de Pós- Graduação em Biologia Comparada. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Max Cardoso Langer Ribeirão Preto - SP 2021 Autorizo a reprodução e divulgação total ou parcial deste trabalho, por qualquer meio convencional ou eletrônico, para fins de estudo e pesquisa, desde que citada a fonte. I authorise the reproduction and total or partial disclosure of this work, via any conventional or electronic medium, for aims of study and research, with the condition that the source is cited. FICHA CATALOGRÁFICA Hermanson, Guilherme Evolution of the skull shape in extinct and extant turtles, 2021. 132 páginas. Dissertação de Mestrado, apresentada à Faculdade de Filosofia, Ciências e Letras de Ribeirão Preto/USP – Área de concentração: Biologia Comparada. -

The Geology of New Mexico As Understood in 1912: an Essay for the Centennial of New Mexico Statehood Part 2 Barry S

Celebrating New Mexico's Centennial The geology of New Mexico as understood in 1912: an essay for the centennial of New Mexico statehood Part 2 Barry S. Kues, Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, New Mexico, [email protected] Introduction he first part of this contribution, presented in the February Here I first discuss contemporary ideas on two fundamental areas 2012 issue of New Mexico Geology, laid the groundwork for an of geologic thought—the accurate dating of rocks and the move- exploration of what geologists knew or surmised about the ment of continents through time—that were at the beginning of Tgeology of New Mexico as the territory transitioned into statehood paradigm shifts around 1912. Then I explore research trends and in 1912. Part 1 included an overview of the demographic, economic, the developing state of knowledge in stratigraphy and paleontol- social, cultural, and technological attributes of New Mexico and its ogy, two disciplines of geology that were essential in understand- people a century ago, and a discussion of important individuals, ing New Mexico’s rock record (some 84% of New Mexico’s surface institutions, and areas and methods of research—the geologic envi- area is covered by sediments or sedimentary rocks) and which were ronment, so to speak—that existed in the new state at that time. advancing rapidly through the first decade of the 20th century. The geologic time scale and age of rocks The geologic time scale familiar to geologists working in New The USGS did not adopt the Paleocene as the earliest epoch of the Mexico in 1912 was not greatly different from that used by modern Cenozoic until 1939. -

Universidad Nacional Del Comahue Centro Regional Universitario Bariloche

Universidad Nacional del Comahue Centro Regional Universitario Bariloche Título de la Tesis Microanatomía y osteohistología del caparazón de los Testudinata del Mesozoico y Cenozoico de Argentina: Aspectos sistemáticos y paleoecológicos implicados Trabajo de Tesis para optar al Título de Doctor en Biología Tesista: Lic. en Ciencias Biológicas Juan Marcos Jannello Director: Dr. Ignacio A. Cerda Co-director: Dr. Marcelo S. de la Fuente 2018 Tesis Doctoral UNCo J. Marcos Jannello 2018 Resumen Las inusuales estructuras óseas observadas entre los vertebrados, como el cuello largo de la jirafa o el cráneo en forma de T del tiburón martillo, han interesado a los científicos desde hace mucho tiempo. Uno de estos casos es el clado Testudinata el cual representa uno de los grupos más fascinantes y enigmáticos conocidos entre de los amniotas. Su inconfundible plan corporal, que ha persistido desde el Triásico tardío hasta la actualidad, se caracteriza por la presencia del caparazón, el cual encierra a las cinturas, tanto pectoral como pélvica, dentro de la caja torácica desarrollada. Esta estructura les ha permitido a las tortugas adaptarse con éxito a diversos ambientes (por ejemplo, terrestres, acuáticos continentales, marinos costeros e incluso marinos pelágicos). Su capacidad para habitar diferentes nichos ecológicos, su importante diversidad taxonómica y su plan corporal particular hacen de los Testudinata un modelo de estudio muy atrayente dentro de los vertebrados. Una disciplina que ha demostrado ser una herramienta muy importante para abordar varios temas relacionados al caparazón de las tortugas, es la paleohistología. Esta disciplina se ha involucrado en temas diversos tales como el origen del caparazón, el origen del desarrollo y mantenimiento de la ornamentación, la paleoecología y la sistemática. -

An Early Bothremydid from the Arlington Archosaur Site of Texas Brent Adrian1*, Heather F

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN An early bothremydid from the Arlington Archosaur Site of Texas Brent Adrian1*, Heather F. Smith1, Christopher R. Noto2 & Aryeh Grossman1 Four turtle taxa are previously documented from the Cenomanian Arlington Archosaur Site (AAS) of the Lewisville Formation (Woodbine Group) in Texas. Herein, we describe a new side-necked turtle (Pleurodira), Pleurochayah appalachius gen. et sp. nov., which is a basal member of the Bothremydidae. Pleurochayah appalachius gen. et sp. nov. shares synapomorphic characters with other bothremydids, including shared traits with Kurmademydini and Cearachelyini, but has a unique combination of skull and shell traits. The new taxon is signifcant because it is the oldest crown pleurodiran turtle from North America and Laurasia, predating bothremynines Algorachelus peregrinus and Paiutemys tibert from Europe and North America respectively. This discovery also documents the oldest evidence of dispersal of crown Pleurodira from Gondwana to Laurasia. Pleurochayah appalachius gen. et sp. nov. is compared to previously described fossil pleurodires, placed in a modifed phylogenetic analysis of pelomedusoid turtles, and discussed in the context of pleurodiran distribution in the mid-Cretaceous. Its unique combination of characters demonstrates marine adaptation and dispersal capability among basal bothremydids. Pleurodira, colloquially known as “side-necked” turtles, form one of two major clades of turtles known from the Early Cretaceous to present 1,2. Pleurodires are Gondwanan in origin, with the oldest unambiguous crown pleurodire dated to the Barremian in the Early Cretaceous2. Pleurodiran fossils typically come from relatively warm regions, and have a more limited distribution than Cryptodira (hidden-neck turtles)3–6. Living pleurodires are restricted to tropical regions once belonging to Gondwana 7,8. -

Geology and Coal Resources of the Upper Cretaceous Fruitland Formation, San Juan Basin, New Mexico and Colorado

Chapter Q National Coal Resource Geology and Coal Resources of the Assessment Upper Cretaceous Fruitland Formation, San Juan Basin, New Mexico and Colorado Click here to return to Disc 1 By James E. Fassett1 Volume Table of Contents Chapter Q of Geologic Assessment of Coal in the Colorado Plateau: Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah Edited by M.A. Kirschbaum, L.N.R. Roberts, and L.R.H. Biewick U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1625–B* 1 U.S. Geological Survey, Denver, Colorado 80225 * This report, although in the USGS Professional Paper series, is available only on CD-ROM and is not available separately U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Contents Abstract........................................................................................................................................................Q1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 2 Purpose and Scope ............................................................................................................................. 2 Location and Extent of Area............................................................................................................... 2 Earlier Investigations .......................................................................................................................... 2 Geography............................................................................................................................................ -

Mesozoic Stratigraphy at Durango, Colorado

160 New Mexico Geological Society, 56th Field Conference Guidebook, Geology of the Chama Basin, 2005, p. 160-169. LUCAS AND HECKERT MESOZOIC STRATIGRAPHY AT DURANGO, COLORADO SPENCER G. LUCAS AND ANDREW B. HECKERT New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, 1801 Mountain Rd. NW, Albuquerque, NM 87104 ABSTRACT.—A nearly 3-km-thick section of Mesozoic sedimentary rocks is exposed at Durango, Colorado. This section con- sists of Upper Triassic, Middle-Upper Jurassic and Cretaceous strata that well record the geological history of southwestern Colorado during much of the Mesozoic. At Durango, Upper Triassic strata of the Chinle Group are ~ 300 m of red beds deposited in mostly fluvial paleoenvironments. Overlying Middle-Upper Jurassic strata of the San Rafael Group are ~ 300 m thick and consist of eolian sandstone, salina limestone and siltstone/sandstone deposited on an arid coastal plain. The Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation is ~ 187 m thick and consists of sandstone and mudstone deposited in fluvial environments. The only Lower Cretaceous strata at Durango are fluvial sandstone and conglomerate of the Burro Canyon Formation. Most of the overlying Upper Cretaceous section (Dakota, Mancos, Mesaverde, Lewis, Fruitland and Kirtland units) represents deposition in and along the western margin of the Western Interior seaway during Cenomanian-Campanian time. Volcaniclastic strata of the overlying McDermott Formation are the youngest Mesozoic strata at Durango. INTRODUCTION Durango, Colorado, sits in the Animas River Valley on the northern flank of the San Juan Basin and in the southern foothills of the San Juan and La Plata Mountains. Beginning at the northern end of the city, and extending to the southern end of town (from north of Animas City Mountain to just south of Smelter Moun- tain), the Animas River cuts in an essentially downdip direction through a homoclinal Mesozoic section of sedimentary rocks about 3 km thick (Figs.