Download Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Asian Paleocene-Early Eocene Chronology and Biotic Events

©Geol. Bundesanstalt, Wien; download unter www.geologie.ac.at Berichte Geol. B.-A., 85 (ISSN 1017-8880) – CBEP 2011, Salzburg, June 5th – 8th Asian Paleocene-Early Eocene Chronology and biotic events Suyin Ting1, Yongsheng Tong2, William C. Clyde3, Paul L.Koch4, Jin Meng5, Yuanqing Wang2, Gabriel J. Bowen6, Qian Li2, Snell E. Kathryn4 1 LSU Museum of Natural Science, Baton Rouge, LA 70803, USA 2 Institute of Vert. Paleont. & Paleoanth., CAS., Beijing 100044, China 3 University of New Hampshire, Durham, NH 03824, USA 4 University of California Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA 95064, USA 5 American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY 10024, USA 6 Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN 47907, USA Biostratigraphic, chemostratigraphic, and magnetostratigraphic studies of the Paleocene and early Eocene strata in the Nanxiong Basin of Guangdong, Chijiang Basin of Jiangxi, Qianshan Basin of Anhui, Hengyang Basin of Hunan, and Erlian Basin of Inner Mongolia, China, in last ten years provide the first well-resolved geochronological constrains on stratigraphic framework for the early Paleogene of Asia. Asian Paleocene and early Eocene strata are subdivided into four biochronological units based on the fossil mammals (Land Mammal Ages). From oldest to youngest, they are the Shanghuan, the Nongshanian, the Gashatan, and the Bumbanian Asian Land Mammal Ages (ALMA). Recent paleomagnetic data from the Nanxiong Basin indicate that the base of the Shanghuan lies about 2/3 the way up Chron C29r. Nanxiong data and recent paleomagnetic and isotopic results from the Chijiang Basin show that the Shanghuan-Nongshanian ALMA boundary lies between the upper part of Chron C27n and the lower part of Chron C26r, close to the Chron C27n-C26r reversal. -

A/L Hcan %Mlsdum

A/LSoxfitateshcan %Mlsdum PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY CENTRAL PARK WEST AT 79TH STREET, NEW YORK 24, N.Y. NUMBER 1957 AUGUST 5, 1959 Fossil Mammals from the Type Area of the Puerco and Nacimiento Strata, Paleocene of New Mexico BY GEORGE GAYLORD SIMPSON ANTECEDENTS The first American Paleocene mammals and the first anywhere from the early to middle Paleocene were found in the San Juan Basin of New Mexico. Somewhat more complete sequences and larger faunas are now known from elsewhere, but the San Juan Basin strata and faunas are classical and are still the standard of comparison for the most clearly established lower (Puercan), middle (Torrejonian), and upper (Tiffanian) stages and ages. The first geologist to distinguish clearly what are now known to be Paleocene beds in the San Juan Basin was Cope in 1S74. He named them "Puercan marls" (Cope, 1875) on the basis of beds along the upper Rio Puerco, and especially of a section west of the Rio Puerco southwest of the then settlement of Nacimiento and of the present town of Cuba, on the southern side of Cuba Mesa. Cope reported no fossils other than petrified wood, but in 1880 and later his collector, David Baldwin, found rather abundant mammals, described by Cope (1881 and later) in beds 50 miles and more to the west and northwest of the type locality but referred to the same formation. In the 1890's Wortman collected for the American Museum in the Puerco of Cope, and, on the basis of this work, Matthew (1897) recognized the presence of two quite distinct faunas of different ages. -

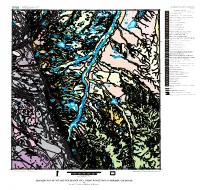

GEOLOGIC MAP of the GREATER DENVER AREA, FRONT RANGE URBAN CORRIDOR, COLORADO by Donald E

U.S DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR MISCELLANEOUS INVESTIGATIONS SERIES I–856–H U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Version 1.1 105°22'30" 105°15' 105°7'30" 105°0' 104°52'30" 104°45' 104°37'30" 40¡0’ 40°0' Qs Qv Ql Qes DESCRIPTION OF MAP UNITS Qco Qp Qlo Kp Qp Kp Kl Kl Qb TKda Ysp Qes Kf Qb Qp Qco Qv Xbc Kp Qb Qes Qp POST-PINEY CREEK AND PINEY CREEK ALLUVIUM (UPPER HOLOCENE) Kl Qes Qes Qco Qlo Qs Qlo Kp Kl Qb Qrf Qls Kf Ql Ysp TKd Qs Qco COLLUVIUM (UPPER HOLOCENE) Xbc Qp Qv Ysp Qp Qb Kl Qv Qes PPf Qp Qco Qco Qrf Kp Qs Qls Qs LANDSLIDE DEPOSITS (HOLOCENE TO MIDDLE? PLEISTOCENE) Qs Qv Kl Qb Qp JPml Kl Qrf Qco Qs Qco Qv Qp Qes WINDBLOWN SAND (LOWER HOLOCENE TO UPPER PLEISTOCENE) Qv Ql TKd Ql Qes Kd Qv Kp Kl Qes Qco River Qco Qp Kf Ql TKda YXp TKda Kl TKda TKd Qs Xbc Qrf Qv Qp Qb Qb BROADWAY ALLUVIUM (UPPER PLEISTOCENE) Qp Qco Qs Qco Qlo Qco Ql Qp Qes Kf Ql Qco Qp Qv Qs Qrf Ql LOESS (UPPER PLEISTOCENE) Qrf Qs Qlo Kf Qs Qco Qco Qp Qes Qp Qco Qp TKd Qb Qco Qlo Qes LOUVIERS ALLUVIUM (UPPER PLEISTOCENE) Xbc Kf Kp Ql Qs Qrf Marshall Qv Qb Ql Kl TKda Qes Qs Kl Lake Qv Qs SLOCUM ALLUVIUM (PLEISTOCENE) Qv Ql Qco JPml Ql Qco PPf Qv Qs Kl Qs Qco Qv Qco Kn Qv Qs Qs Kp Qrf Qb Qb Barr Lake Kcgg Qv VERDOS ALLUVIUM (PLEISTOCENE) Qs Qrf Qco Ql TKda Qlo Qp Qs TKda Qp Ql TKda Xqm Qlo Qrf Qs Qs Qs ROCKY FLATS ALLUVIUM (PLEISTOCENE) Qp Xq Kd Kf Qco Qp Qco Qb Kl Kp Qco Platte Qlo Qb Qrf Qs Qn Qls Qco NUSSBAUM ALLUVIUM (PLEISTOCENE) Kp Qco Qp Xbc TKd Qrf Qrf Qv Qco Tg Qv Qv HIGH-LEVEL GRAVEL DEPOSITS (PLIOCENE TO OLIGOCENE) Xbc Qp PPf Qb TKd Qb Qv TKda JPml Qv Ql Tcr CASTLE ROCK -

Geology and Mineral Resources of Sierra Nacimiento and Vicinity, New

iv Contents ABSTRACT 7 TERTIARY-QUATERNARY 47 INTRODUCTION 7 QUATERNARY 48 LOCATION 7 Bandelier Tuff 48 PHYSIOGRAPHY 9 Surficial deposits 48 PREVIOUS WORK 9 PALEOTECTONIC SETTING 48 ROCKS AND FORMATIONS 9 REGIONAL TECTONIC SETTING 49 PRECAMBRIAN 9 STRUCTURE 49 Northern Nacimiento area 9 NACIMIENTO UPLIFT 49 Southern Nacimiento area 15 Nacimiento fault 51 CAMBRIAN-ORDOVICIAN (?) 20 Pajarito fault 52 MISSISSIPPIAN 20 Synthetic reverse faults 52 Arroyo Peñasco Formation 20 Eastward-trending faults 53 Log Springs Formation 21 Trail Creek fault 53 PENNSYLVANIAN 21 Antithetic reverse faults 53 Osha Canyon Formation 23 Normal faults 53 Sandia Formation 23 Folds 54 Madera Formation 23 SAN JUAN BASIN 55 Paleotectonic interpretation 25 En echelon folds 55 PERMIAN 25 Northeast-trending faults 55 Abo Formation 25 Synclinal bend 56 Yeso Formation 27 Northerly trending normal faults 56 Glorieta Sandstone 30 Antithetic reverse faults 56 Bernal Formation 30 GALLINA-ARCHULETA ARCH 56 TRIASSIC 30 CHAMA BASIN 57 Chinle Formation 30 RIΟ GRANDE RIFT 57 JURASSIC 34 JEMEZ VOLCANIC FIELD 59 Entrada Sandstone 34 TECTONIC EVOLUTION 60 Todilto Formation 34 MINERAL AND ENERGY RESOURCES 63 Morrison Formation 34 COPPER 63 Depositional environments 37 Mineralization 63 CRETACEOUS 37 Origin 67 Dakota Formation 37 AGGREGATE 69 Mancos Shale 39 TRAVERTINE 70 Mesaverde Group 40 GYPSUM 70 Lewis Shale 41 COAL 70 Pictured Cliffs Sandstone 41 ΗUMΑTE 70 Fruitland Formation and Kirtland Shale URANIUM 70 undivided 42 GEOTHERMAL ENERGY 72 TERTIARY 42 OIL AND GAS 72 Ojo Alamo Sandstone -

Download File

Chronology and Faunal Evolution of the Middle Eocene Bridgerian North American Land Mammal “Age”: Achieving High Precision Geochronology Kaori Tsukui Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2016 © 2015 Kaori Tsukui All rights reserved ABSTRACT Chronology and Faunal Evolution of the Middle Eocene Bridgerian North American Land Mammal “Age”: Achieving High Precision Geochronology Kaori Tsukui The age of the Bridgerian/Uintan boundary has been regarded as one of the most important outstanding problems in North American Land Mammal “Age” (NALMA) biochronology. The Bridger Basin in southwestern Wyoming preserves one of the best stratigraphic records of the faunal boundary as well as the preceding Bridgerian NALMA. In this dissertation, I first developed a chronological framework for the Eocene Bridger Formation including the age of the boundary, based on a combination of magnetostratigraphy and U-Pb ID-TIMS geochronology. Within the temporal framework, I attempted at making a regional correlation of the boundary-bearing strata within the western U.S., and also assessed the body size evolution of three representative taxa from the Bridger Basin within the context of Early Eocene Climatic Optimum. Integrating radioisotopic, magnetostratigraphic and astronomical data from the early to middle Eocene, I reviewed various calibration models for the Geological Time Scale and intercalibration of 40Ar/39Ar data among laboratories and against U-Pb data, toward the community goal of achieving a high precision and well integrated Geological Time Scale. In Chapter 2, I present a magnetostratigraphy and U-Pb zircon geochronology of the Bridger Formation from the Bridger Basin in southwestern Wyoming. -

Forgotten Crocodile from the Kirtland Formation, San Juan Basin, New

posed that the narial cavities of Para- Wima1l- saurolophuswere vocal resonating chambers' Goniopholiskirtlandicus Apparently included with this material shippedto Wiman was a partial skull that lromthe Wiman describedas a new speciesof croc- forgottencrocodile odile, Goniopholis kirtlandicus. Wiman publisheda descriptionof G. kirtlandicusin Basin, 1932in the Bulletin of the GeologicalInstitute KirtlandFormation, San Juan of IJppsala. Notice of this specieshas not appearedin any Americanpublication. Klilin NewMexico (1955)presented a descriptionand illustration of the speciesin French, but essentially repeatedWiman (1932). byDonald L. Wolberg, Vertebrate Paleontologist, NewMexico Bureau of lVlinesand Mineral Resources, Socorro, NIM Localityinformation for Crocodilian bone, armor, and teeth are Goni o p holi s kir t landicus common in Late Cretaceous and Early Ter- The skeletalmaterial referred to Gonio- tiary deposits of the San Juan Basin and pholis kirtlandicus includesmost of the right elsewhere.In the Fruitland and Kirtland For- side of a skull, a squamosalfragment, and a mations of the San Juan Basin, Late Creta- portion of dorsal plate. The referral of the ceous crocodiles were important carnivores of dorsalplate probably represents an interpreta- the reconstructed stream and stream-bank tion of the proximity of the material when community (Wolberg, 1980). In the Kirtland found. Figs. I and 2, taken from Wiman Formation, a mesosuchian crocodile, Gonio- (1932),illustrate this material. pholis kirtlandicus, discovered by Charles H. Wiman(1932, p. 181)recorded the follow- Sternbergin the early 1920'sand not described ing locality data, provided by Sternberg: until 1932 by Carl Wiman, has been all but of Crocodile.Kirtland shalesa 100feet ignored since its description and referral. "Skull below the Ojo Alamo Sandstonein the blue Specimensreferred to other crocodilian genera cley. -

CRETACEOUS-TERTIARY BOUNDARY Ijst the ROCKY MOUNTAIN REGION1

BULLETIN OF THE GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA V o l..¿5, pp. 325-340 September 15, 1914 PROCEEDINGS OF THE PALEONTOLOGICAL SOCIETY CRETACEOUS-TERTIARY BOUNDARY IjST THE ROCKY MOUNTAIN REGION1 BY P. H . KNOWLTON (Presented before the Paleontological Society December 31, 1913) CONTENTS Page Introduction........................................................................................................... 325 Stratigraphic evidence........................................................................................ 325 Paleobotanical evidence...................................................................................... 331 Diastrophic evidence........................................................................................... 334 The European time scale.................................................................................. 335 Vertebrate evidence............................................................................................ 337 Invertebrate evidence.......................................................................................... 339 Conclusions............................................................................................................ 340 I ntroduction The thesis of this paper is as follows: It is proposed to show that the dinosaur-bearing beds known as “Ceratops beds,” “Lance Creek bieds,” Lance formation, “Hell Creek beds,” “Somber beds,” “Lower Fort Union,”- Laramie of many writers, “Upper Laramie,” Arapahoe, Denver, Dawson, and their equivalents, are above a major -

Basin-Margin Depositional Environments of the Fort Union and Wasatch Formations in the Buffalo-Lake De Smet Area, Johnson County, Wyoming

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Basin-Margin Depositional Environments of the Fort Union and Wasatch Formations in the Buffalo-Lake De Smet area, Johnson County, Wyoming By Stanley L. Obernyer Open-File Report 79-712 1979 Contents Page Abstract 1 Introduction 5 Methods of investigation 8 Previ ous work - 9 General geol ogy 10 Acknowledgments 16 Descriptive stratigraphy of the Fort Union and Wasatch Formations 18 Fort Union Formation- 18 Lower member 20 Conglomerate member 21 Wasatch Formation 30 Kingsbury Conglomerate Member 32 Moncrief Member 38 Coal-bearing strata Wasatch Formation 45 Conglomeratic sandstone sequence 46 The Lake De Smet coal bed 53 Very fine to medium-grained sandstone sequence 69 Fossil marker beds 78 Environments of Deposition 79 General 79 Alluvial fan environment 82 Braided stream environments 86 Alluvial valley environments 89 Tectonics and Sedimentation 92 Conglomerates and tectonics- 92 Coals and tectonics 98 Conclusions 108 References 111 11 ILLUSTRATIONS Plates Plate 1. Bedrock geologic map of the Buffalo-Lake De Smet area, Johnson County, Wyoming In pocket 2. Geologic cross sections along the Bighorn Mountain Front, Buffalo-Lake De Smet area, Johnson County, Wyoming In pocket FIGURES Page Figure 1. Location map sh wing the major structural units surround ing the Powder River Basin, Wyoming and Montana 7 2. Composite geologic section of the rocks exposed in in the Buffalo-Lake De Smet area- 11 3. Generalized geologic map of the Powder River Basin 12 4. Isopach map of the Fort Union and Wasatch Formations, Powder River Basin, from Curry (1971) 14 5. Generalized stratigraphic column of the conglomerate sequences 19 6. -

Stratigraphy of the Upper Cretaceous Fox Hills Sandstone and Adjacent

Stratigraphy of the Upper Cretaceous Fox Hills Sandstone and AdJa(-erit Parts of the Lewis Sliale and Lance Formation, East Flank of the Rock Springs Uplift, Southwest lo U.S. OEOLOGI AL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1532 Stratigraphy of the Upper Cretaceous Fox Hills Sandstone and Adjacent Parts of the Lewis Shale and Lance Formation, East Flank of the Rock Springs Uplift, Southwest Wyoming By HENRYW. ROEHLER U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1532 Description of three of/lapping barrier shorelines along the western margins of the interior seaway of North America UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1993 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L. Peck, Director Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Roehler, Henry W. Stratigraphy of the Upper Cretaceous Fox Hills sandstone and adjacent parts of the Lewis shale and Lance formation, east flank of the Rock Springs Uplift, southwest Wyoming / by Henry W. Roehler. p. cm. (U.S. Geological Survey professional paper ; 1532) Includes bibliographical references. Supt.ofDocs.no.: I19.16:P1532 1. Geology, Stratigraphic Cretaceous. 2. Geology Wyoming. 3. Fox Hills Formation. I. Geological Survey (U.S.). II. Title. III. Series. QE688.R64 1993 551.7T09787 dc20 92-36645 CIP For sale by USGS Map Distribution Box 25286, Building 810 Denver Federal Center Denver, CO 80225 CONTENTS Page Page Abstract......................................................................................... 1 Stratigraphy Continued Introduction................................................................................... 1 Formations exposed on the east flank of the Rock Springs Description and accessibility of the study area ................ -

The Geology of New Mexico As Understood in 1912: an Essay for the Centennial of New Mexico Statehood Part 2 Barry S

Celebrating New Mexico's Centennial The geology of New Mexico as understood in 1912: an essay for the centennial of New Mexico statehood Part 2 Barry S. Kues, Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, New Mexico, [email protected] Introduction he first part of this contribution, presented in the February Here I first discuss contemporary ideas on two fundamental areas 2012 issue of New Mexico Geology, laid the groundwork for an of geologic thought—the accurate dating of rocks and the move- exploration of what geologists knew or surmised about the ment of continents through time—that were at the beginning of Tgeology of New Mexico as the territory transitioned into statehood paradigm shifts around 1912. Then I explore research trends and in 1912. Part 1 included an overview of the demographic, economic, the developing state of knowledge in stratigraphy and paleontol- social, cultural, and technological attributes of New Mexico and its ogy, two disciplines of geology that were essential in understand- people a century ago, and a discussion of important individuals, ing New Mexico’s rock record (some 84% of New Mexico’s surface institutions, and areas and methods of research—the geologic envi- area is covered by sediments or sedimentary rocks) and which were ronment, so to speak—that existed in the new state at that time. advancing rapidly through the first decade of the 20th century. The geologic time scale and age of rocks The geologic time scale familiar to geologists working in New The USGS did not adopt the Paleocene as the earliest epoch of the Mexico in 1912 was not greatly different from that used by modern Cenozoic until 1939. -

Analysis and Correlation of Growth

ANALYSIS AND CORRELATION OF GROWTH STRATA OF THE CRETACEOUS TO PALEOCENE LOWER DAWSON FORMATION: INSIGHT INTO THE TECTONO-STRATIGRAPHIC EVOLUTION OF THE COLORADO FRONT RANGE by Korey Tae Harvey A thesis submitted to the Faculty and Board of Trustees of the Colorado School of Mines in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science (Geology). Golden, Colorado Date __________________________ Signed: ________________________ Korey Harvey Signed: ________________________ Dr. Jennifer Aschoff Thesis Advisor Golden, Colorado Date ___________________________ Signed: _________________________ Dr. Paul Santi Professor and Head Department of Geology and Geological Engineering ii ABSTRACT Despite numerous studies of Laramide-style (i.e., basement-cored) structures, their 4-dimensional structural evolution and relationship to adjacent sedimentary basins are not well understood. Analysis and correlation of growth strata along the eastern Colorado Front Range (CFR) help decipher the along-strike linkage of thrust structures and their affect on sediment dispersal. Growth strata, and the syntectonic unconformities within them, record the relative roles of uplift and deposition through time; when mapped along-strike, they provide insight into the location and geometry of structures through time. This paper presents an integrated structural- stratigraphic analysis and correlation of three growth-strata assemblages within the fluvial and fluvial megafan deposits of the lowermost Cretaceous to Paleocene Dawson Formation on the eastern CFR between Colorado Springs, CO and Sedalia, CO. Structural attitudes from 12 stratigraphic profiles at the three locales record dip discordances that highlight syntectonic unconformities within the growth strata packages. Eight traditional-type syntectonic unconformities were correlated along-strike of the eastern CFR distinguish six phases of uplift in the central portion of the CFR. -

Stratigraphic Correlation Chart for Western Colorado and Northwestern New Mexico

New Mexico Geological Society Guidebook, 32nd Field Conference, Western Slope Colorado, 1981 75 STRATIGRAPHIC CORRELATION CHART FOR WESTERN COLORADO AND NORTHWESTERN NEW MEXICO M. E. MacLACHLAN U.S. Geological Survey Denver, Colorado 80225 INTRODUCTION De Chelly Sandstone (or De Chelly Sandstone Member of the The stratigraphic nomenclature applied in various parts of west- Cutler Formation) of the west side of the basin is thought to ern Colorado, northwestern New Mexico, and a small part of east- correlate with the Glorieta Sandstone of the south side of the central Utah is summarized in the accompanying chart (fig. 1). The basin. locations of the areas, indicated by letters, are shown on the index map (fig. 2). Sources of information used in compiling the chart are Cols. B.-C. shown by numbers in brackets beneath the headings for the col- Age determinations on the Hinsdale Formation in parts of the umns. The numbers are keyed to references in an accompanying volcanic field range from 4.7 to 23.4 m.y. on basalts and 4.8 to list. Ages where known are shown by numbers in parentheses in 22.4 m.y. on rhyolites (Lipman, 1975, p. 6, p. 90-100). millions of years after the rock name or in parentheses on the line The early intermediate-composition volcanics and related rocks separating two chronostratigraphic units. include several named units of limited areal extent, but of simi- No Quaternary rocks nor small igneous bodies, such as dikes, lar age and petrology—the West Elk Breccia at Powderhorn; the have been included on this chart.