Next Year in Jerusalem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jewish Subcultures Online: Outreach, Dating, and Marginalized Communities ______

JEWISH SUBCULTURES ONLINE: OUTREACH, DATING, AND MARGINALIZED COMMUNITIES ____________________________________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Fullerton ____________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in American Studies ____________________________________ By Rachel Sara Schiff Thesis Committee Approval: Professor Leila Zenderland, Chair Professor Terri Snyder, Department of American Studies Professor Carrie Lane, Department of American Studies Spring, 2016 ABSTRACT This thesis explores how Jewish individuals use and create communities online to enrich their Jewish identity. The Internet provides Jews who do not fit within their brick and mortar communities an outlet that gives them voice, power, and sometimes anonymity. They use these websites to balance their Jewish identities and other personal identities that may or may not fit within their local Jewish community. This research was conducted through analyzing a broad range of websites. The first chapter, the introduction, describes the Jewish American population as a whole as well as the history of the Internet. The second chapter, entitled “The Black Hats of the Internet,” discusses how the Orthodox community has used the Internet to create a modern approach to outreach. It focuses in particular on the extensive web materials created by Chabad and Aish Hatorah, which offer surprisingly modern twists on traditional texts. The third chapter is about Jewish online dating. It uses JDate and other secular websites to analyze how Jewish singles are using the Internet. This chapter also suggests that the use of the Internet may have an impact on reducing interfaith marriage. The fourth chapter examines marginalized communities, focusing on the following: Jewrotica; the Jewish LGBT community including those who are “OLGBT” (Orthodox LGBT); Punk Jews; and feminist Jews. -

Jointorah Education Revolution

the JOIN TORAH EDUCATION REVOLUTION Afikei Torah • Ahavas Torah • Ahava V'achva • Aish HaTorah of Cleveland • Aish HaTorah of Denver • Aish HaTorah of Detroit • Aish HaTorah of Jerusalem • Aish HaTorah of Mexico • Aish HaTorah of NY • Aish HaTorah of Philadelphia • Aish HaTorah of St Louis • Aish HaTorah of Thornhill • Ateres Yerushalayim • Atlanta Scholars Kollel • AZ Russian Programs • Bais Yaakov of Boston • Bais Yaakov of LA • Bar Ilan University • Batya Girls / Torah Links • Bay Shore Jewish Center Be'er Miriam • Belmont Synagogue • Beth Din • Beth Jacob • Beth Jacob Congregation • Beth Tfiloh Upper School Library • Bnei Shalom Borehamwood & • Elstree Synagogue • Boston's Jewish Community Day School • Brandywine Hills Minyan • Calabasas Shul • Camp Bnos Agudah • Chabad at the Beaches • Chabad Chabad of Montreal • Chai Center of West Bay • Chaye Congregation Ahavat Israel Chabad Impact of Torah Live Congregation Beth Jacob of Irvine • Congregation Light of Israel Congregation Derech (Ohr Samayach) Organizations that have used Etz Chaim Center for Jewish Studies Hampstead Garden Suburb Synagogue • Torah Live materials Jewish Community Day Jewish FED of Greater Atlanta / Congregation Ariel • Jewish 600 Keneseth Beth King David Linksfield Primary and High schools • King 500 Mabat • Mathilda Marks Kennedy Jewish Primary School • Me’or 400 Menorah Shul • Meor Midreshet Rachel v'Chaya 206 MTA • Naima Neve Yerushalayim • 106 Ohab Zedek • Ohr Pninim Seminary • 77 Rabbi Reisman Yarchei Kalla • Rabbi 46 Shapell's College • St. John's Wood Synagogue • The 14 Tiferes High Machon Shlomo 1 Me’or HaTorah Meor • Me'or Midreshet Rachel v'Chaya College • Naima Neve Yerushalayim • Ohab Zedek • Ohr Pninim Seminary • Rabbi Reisman Yarchei Kalla • Rabbi 2011 2014 2016 2010 2015 2013 2012 2008 2009 Shapell's College St. -

T S Form, 990-PF Return of Private Foundation

t s Form, 990-PF Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Department of the Treasury Treated as a Private Foundation Internal Revenue service Note. The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state report! 2006 For calendar year 2006, or tax year beginning , and ending G Check all that a Initial return 0 Final return Amended return Name of identification Use the IRS foundation Employer number label. Otherwise , HE DENNIS BERMAN FAMILY FOUNDATION INC 31-1684732 print Number and street (or P O box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite Telephone number or type . 5410 EDSON LANE 220 301-816-1555 See Specific City or town, and ZIP code C If exemption application is pending , check here l_l Instructions . state, ► OCKVILLE , MD 20852-3195 D 1. Foreign organizations, check here Foreign organizations meeting 2. the 85% test, ► H Check type of organization MX Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation check here and attach computation = Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt chartable trust 0 Other taxable private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method 0 Cash Accrual under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here (from Part ll, col (c), line 16) 0 Other (specify) F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination $ 5 010 7 3 9 . (Part 1, column (d) must be on cash basis) under section 507 (b)( 1 ► )( B ) , check here ► ad 1 Analysis of Revenue and Expenses ( a) Revenue and ( b) Net investment (c) Adjusted net ( d) Disbursements (The total of amounts in columns (b), (c), and (d) may not for chartable purposes necessary equal the amounts in column (a)) expenses per books income income (cash basis only) 1 Contributions , gifts, grants , etc , received 850,000 . -

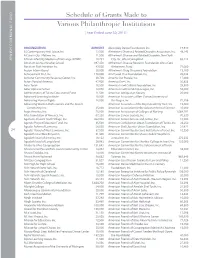

Schedule of Grants Made to Various Philanthropic Institutions

2011 ANNUAL REPORT 2011 ANNUAL Schedule of Grants Made to Grants Various Philanthropic Institutions American Folk Art Museum 127,350 American Friends of the College of American Friends of Agudat Shetile Zetim, Inc. 10,401 Management, Inc. 10,000 [ Year ended June 30, 2011 ] American Friends of Aish Hatorah - American Friends of the Hebrew University, Inc. 77,883 Western Region, Inc. 10,500 American Friends of the Israel Free Loan American Friends of Alyn Hospital, Inc. 39,046 Association, Inc. 55,860 ORGANIZATION AMOUNT All 4 Israel, Inc. 16,800 American Friends of Aram Soba 23,932 American Friends of the Israel Museum 1,053,000 13 Plus Chai, Inc. 82,950 Allen-Stevenson School 25,000 American Friends of Ateret Cohanem, Inc. 16,260 American Friends of the Israel Philharmonic 52nd Street Project, Inc. 125,000 Alley Pond Environmental Center, Inc. 50,000 American Friends of Batsheva Dance Company, Inc. 20,000 Orchestra, Inc. 320,850 A.B.C., Inc. of New Canaan 10,650 Alliance for Cancer Gene Therapy, Inc. 44,950 The American Friends of Beit Issie Shapiro, Inc. 70,910 American Friends of the Jordan River A.J. Muste Memorial Institute 15,000 Alliance for Children Foundation, Inc. 11,778 American Friends of Beit Morasha 42,360 Village Foundation 16,000 JEWISH COMMUNAL FUND JEWISH COMMUNAL Aaron Davis Hall, Inc. d/b/a Harlem Stage 125,000 Alliance for School Choice, Inc. 25,000 American Friends of Beit Orot, Inc. 44,920 American Friends of the Old City Cheder in Abingdon Theatre Company 30,000 Alliance for the Arts, Inc. -

Vertientes Del Judaismo #3

CLASES DE JUDAISMO VERTIENTES DEL JUDAISMO #3 Por: Eliyahu BaYonah Director Shalom Haverim Org New York Vertientes del Judaismo • LA ORTODOXIA MODERNA • La Ortodoxia moderna comprende un espectro bastante amplio de movimientos, cada extracción toma varias filosofías aunque relacionados distintamente, que en alguna combinación han proporcionado la base para todas las variaciones del movimiento de hoy en día. • En general, la ortodoxia moderna sostiene que la ley judía es normativa y vinculante, y concede al mismo tiempo un valor positivo para la interacción con la sociedad contemporánea. Vertientes del Judaismo • LA ORTODOXIA MODERNA • En este punto de vista, el judaísmo ortodoxo puede "ser enriquecido" por su intersección con la modernidad. • Además, "la sociedad moderna crea oportunidades para ser ciudadanos productivos que participan en la obra divina de la transformación del mundo en beneficio de la humanidad". • Al mismo tiempo, con el fin de preservar la integridad de la Halajá, cualquier área de “fuerte inconsistencia y conflicto" entre la Torá y la cultura moderna debe ser evitada. La ortodoxia moderna, además, asigna un papel central al "Pueblo de Israel " Vertientes del Judaismo • LA ORTODOXIA MODERNA • La ortodoxia moderna, como una corriente del judaísmo ortodoxo representado por instituciones como el Consejo Nacional para la Juventud Israel, en Estados Unidos, es pro-sionista y por lo tanto da un estatus nacional, así como religioso, de mucha importancia en el Estado de Israel, y sus afiliados que son, por lo general, sionistas en la orientación. • También practica la implicación con Judíos no ortodoxos que se extiende más allá de "extensión (kiruv)" a las relaciones institucionales y la cooperación continua, visto como Torá Umaddá. -

JCF-2018-Annual-Report.Pdf

JEWISH COMMUNAL FUND 2018 ANNUAL REPORT Since 2000, Jewish Communal Fund’s generous Fundholders have made nearly $5 Billion in grants to charities in all sectors, including: + GRANTS 300,000 to Jewish organizations in the United States, totaling nearly $2 Billion + GRANTS 100,000 to Israeli and international charities, totaling $664 Million + GRANTS 200,000 to general charities in the United States, totaling $2.4 Billion CONTENTS 1 Letter from President and CEO 2 JCF Reinvests in the Jewish Community 3 JCF Adds Social Impact Investments in Every Asset Class 4 Investments 5–23 Financial Statements 24–37 Grants 38–55 Funds 56 Trustees/Staff 2018 ANNUAL REPORT ANNUAL 2018 very year, we are humbled by the enormous generosity of JCF’s Fundholders. FY 2018 was no exception—our Fundholders recommended a staggering 58,000 grants totaling $435 million to charities in every sector. It is our privilege to facilitate your grant- Emaking, and we are pleased to report a record-breaking year of growth and service to the Jewish community. By choosing JCF to facilitate your charitable giving, you further enable us to make an annual $2 million unrestricted grant to UJA-Federation of New York, to support local Jewish programs and initiatives. In addition, JCF’s endowment, the Special Gifts Fund, continues to change lives for the better, granting out more than $17 million since 1999. Your grants and ours combine to create a double bottom line. Grants from the Special Gifts Fund are the way that our JCF network collectively expresses its support for the larger Jewish community, and this sets JCF apart from all other donor advised funds. -

Schedule of Grants Made to Various

Schedule of Grants Made to Various Philanthropic Institutions [ Year Ended June 30, 2015 ] ORGANIZATION AMOUNT Alvin Ailey Dance Foundation, Inc. 19,930 3S Contemporary Arts Space, Inc. 12,500 Alzheimer’s Disease & Related Disorders Association, Inc. 46,245 A Cure in Our Lifetime, Inc. 11,500 Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders, New York A Torah Infertility Medium of Exchange (ATIME) 20,731 City, Inc. d/b/a CaringKind 65,215 Abraham Joshua Heschel School 397,450 Alzheimer’s Disease Research Foundation d/b/a Cure JEWISH COMMUNAL FUND JEWISH COMMUNAL Abraham Path Initiative, Inc. 42,500 Alzheimer’s Fund 71,000 Accion International 30,000 Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation 15,100 Achievement First, Inc. 170,000 Am Yisroel Chai Foundation, Inc. 25,036 Achiezer Community Resource Center, Inc. 20,728 Ameinu Our People, Inc. 17,000 Actors Fund of America 47,900 America Gives, Inc. 30,856 Adas Torah 16,500 America-Israel Cultural Foundation, Inc. 25,500 Adler Aphasia Center 14,050 America-Israel Friendship League, Inc. 55,000 Administrators of Tulane Educational Fund 11,500 American Antiquarian Society 25,000 Advanced Learning Institute 10,000 American Associates of Ben-Gurion University of Advancing Human Rights 18,000 the Negev, Inc. 71,386 Advancing Women Professionals and the Jewish American Associates of the Royal Academy Trust, Inc. 15,000 Community, Inc. 25,000 American Association for the Advancement of Science 35,000 Aegis America, Inc. 75,000 American Association of Colleges of Nursing 1,064,797 Afya Foundation of America, Inc. 67,250 American Cancer Society, Inc. -

2020 Grants Book

REPORT OF GRANTS AWARDED 2019-2020 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 2 What We Do — And How We Do It 2 Where Our Dollars Go 3 Fiscal Year 2020 Grants by Agency: Full Listing 4 Named Endowments and Spending Funds 40 2020 Leadership List 46 4 INTRODUCTION A YEAR LIKE NO OTHER In a typical year, this grants book would be an important record of our shared investments in our community. The year 2020 has been anything but typical. While this report still documents our collective grant making, reflecting our commitment to the highest degree of programmatic integrity and true fiscal transparency, it is also a testament to the heroic efforts that have kept critical services and mission-driven programs going despite a global pandemic. For so many individuals, day-to-day life is a regular series of obstacles and uncertainties. Multiply that by millions of people impacted by Covid-19, and you have some sense of what has been required to assure that we are remaining true to UJA-Federation’s mission to care, connect, and inspire. So, while this is a report of our annual accomplishment, it is also a tribute to the unwavering determination of professionals and volunteers within UJA, at agencies and in neighborhoods, on front lines and on screens, who have simply refused to allow a novel virus to alter decades-old commitments in New York, in Israel, and around the world. This fortitude required stunning acts of generosity. We continue to honor the system created by UJA’s founders that not only has stood the test of time but continues to shape the future of our collective story. -

The Baal Teshuva Movement

TAMUZ, 57 40 I JUNE, 19$0 VOLUME XIV, NUMBER 9 $1.25 ' ' The Baal Teshuva Movement Aish Hatorah • Bostoner Rebbe: Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Horowitz• CHABAD • Dvar Yerushalayim • Rabbi Shlomo · Freifeld • Gerrer Rebbe • Rabbi Baruch ·.. Horowitz • Jewish Education Progra . • Kosel Maarovi • Moreshet Avot/ El HaMekorot • NCSY • Neve Yerushalayim •Ohr Somayach . • P'eylim •Rabbi Nota Schiller• Sh' or Yashuv •Rabbi Meir Shuster • Horav Elazar Shach • Rabbi Mendel Weinbach •Rabbi Noach Weinberg ... and much much more. THE JEWISH BSERVER In this issue ... THE BAAL TESHUVA MOVEMENT Prologue . 1 4 Chassidic Insights: Understanding Others Through Ourselves, Rabbi Levi Yitzchok Horowitz. 5 A Time to Reach Out: "Those Days Have Come," Rabbi Baruch Horovitz 8 The First Step: The Teshuva Solicitors, Rabbi Hillel Goldberg 10 Teaching the Men: Studying Gemora-The Means and the Ends of the Teshuva Process, Rabbi Nola Schiller . 13 Teaching the Women: How to Handle a Hungry Heart, Hanoch Teller 16 THE JEWISH OBSERVER (ISSN Watching the Airplanes, Abraham ben Shmuel . 19 0(121-6615) is published monthly, Kiruv in Israel: except Ju!y and August. by the Bringing Them to our Planet, Ezriel Hildesheimer 20 Agudath Israel of America, 5 Beekman Street, New York, N.Y The Homecoming Ordeal: 10038. Second class postage paid Helping the Baal Teshuva in America, at New York, N.Y. Subscription Rabbi Mendel Weinbach . 25 $9.00 per year; two years. $17.50; three years, $25.00; outside of the The American Scene: United States, $10.00 per year. A Famine in the Land, Avrohom Y. HaCohen 27 Single copy, $1.25 Printed in the U.S.A. -

How to Prevent an Intermarriage

How To Prevent an Intermarriage A guide for preventing broken hearts How To Prevent an Intermarriage A guide for preventing broken hearts Rabbi Kalman Packouz © 2004 by Rabbi Kalman Packouz First edition, 1976; Second edition, 1982 Third revised and expanded edition, 2004 Aish HaTorah P.O.B. 14149 Jerusalem, Israel Tel. 9722-628-5666 To contact Rabbi Packouz: 3150 Sheridan Avenue Miami Beach, Fl. 33140 Telephone: (305) 535-2474 Fax: (305) 531-9334 E-mail: [email protected] For a free internet subscription to Rabbi Packouz's Shabbat Shalom Weekly -- Insights into life, personal growth and Torah which is read each week by over 200,000 people – either subscribe from www.shabbatshalom.org or at aish.com/torahportion/shalomweekly Go to www.preventintermarriage.com for more information and free downloads Permission is granted to photocopy whatever sections of this book you may need to communicate with someone you love the benefits of marrying someone Jewish and/or the problems facing an intermarriage. ISBN: 0-87306-371-6 Typeset by: Rosalie Lerch Intermarriage is a recognized threat to the survival of the Jewish people. There is a sore need to meet this threat. After reading How to Stop an Intermarriage twenty years ago before it was published, I wrote, "I am very much encouraged. As the first book in its field, it is more than a beginning. It is excellently done, with cogent arguments, effective suggestions, and positive approaches. It will definitely be an invaluable aid for those who want to know what they can do at this time of crisis." Now the book has proven itself as an effective tool which has helped thousands of parents in their time of need. -

The Great American Jewish Awakening : Jonathan Sarna · · ------·------"--·-----··-~·---·-·-·--~

/ -·' , -4 OCTOBER, 1982 VOLUME XXVIn, No. 8 The Great American Jewish Awakening : Jonathan Sarna · · ------·------"--·-----··-~·---·-·-·--~--. -----..---··---· ~--~---- ESSAY 0 The Great American Jewish Awakening JONATHAN D. SARNA bservers of the American jewish scene agree that· In the major Jewish religious movements, the same an important change has taken place in the last transformation can be seen. A new series of pamphlet~ O 10 years. There is talk of a "Jewish revival,'' "a by Daniel B. Syme, "highlighting the why and how of reawakening of American Jewish life," and a "revitaliza Jewish living in the home" reflects developments· that tion ofJewish tradition." Orthodox Judaism claims to be have taken place in Reform Jewish circles. The guide1 gaining strength,. its ranks swelled by; according to one aim specifically at encouraging ritual observance; the) estimate, "tens. of thousands" of baale teshuva,Jew~ who are a far cry from old Union of American Hebrew adopt the lifestyle of the faithful. At least one Jewish Congregation pamphlets devoted to such ponderous journalist predicts that we are living in an "apocalyptic topics as "The Faith and Message of the Prophets;· time." "jewish Ethics," and "The Universal Lord." In Reforrr· Hyperbole notwithstanding, American judaism Judaism· today one encounters Jews who pray· with really has undergone a transformation. Many remain heads covered and shoulders draped in a talis, Jews whv unaffected; some recoil in horror. Still, across the spec observe dietary laws, and Jews who stricdy observe the trum of Jewish life new interest in tradition and ritual Sabbath. Classical Reform, with its disdain for tradition manifests itself. To take just an example, the General and neglect of ritual, claims fewer and fewer adherents. -

CCAR RESPONSA Solicitation of Synagogue Members by Other Jewish Organizations She'elah Teshuvah

CCAR RESPONSA 5763.1 Solicitation of Synagogue Members by Other Jewish Organizations She'elah In many communities, organizations such as Chabad, Aish HaTorah and others either directly or indirectly solicit members of existing congregations for programs, activities, worship and financial support. Are these practices ethical according to Jewish tradition? Does such solicitation or even ministering to members of existing congregations transgress the prohibition of hasagat gevul? (Rabbi Ned Soltz, Fullerton, CA) Teshuvah Our canons of professional practice, as embodied in the CCAR’s Code of Ethics for Rabbis, expressly forbid us from rendering “pastoral attentions to members of other congregations, havurot, and other religious institutions” if such attentions would harm collegial or institutional relationships. A rabbi, moreover, “should neither solicit nor sanction efforts to solicit members of another congregation.”[1] It is clear, therefore, that by our own takanah, or authoritative legislative enactment, it would be wrong for rabbis and synagogues to engage in the practices described in our she’elah. The problem, of course, is that the Code of Ethics is binding only upon members of the CCAR; it does not apply to other rabbis or to organizations such as Chabad and Aish HaTorah. Hence, our sho’el asks whether such solicitation is prohibited by traditional Jewish law and ethics, that is, by standards that are independent of our own rabbinical community and that other religious Jews would find persuasive and compelling. In particular, our she’elah points to the principle of hasagat gevul, a term drawn from the Torah’s prohibition against removing the boundary markers that separate one’s property from that of one’s neighbor (Deuteronomy 19:14 and 27:17).