GEOFF BULL: an INTERVIEW by Eric Myers ______

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wavelength (April 1981)

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO Wavelength Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies 4-1981 Wavelength (April 1981) Connie Atkinson University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength Recommended Citation Wavelength (April 1981) 6 https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength/6 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies at ScholarWorks@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wavelength by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. APRIL 1 981 VOLUME 1 NUMBE'J8. OLE MAN THE RIVER'S LAKE THEATRE APRIL New Orleans Mandeville, La. 6 7 8 9 10 11 T,HE THE THIRD PALACE SUCK'S DIMENSION SOUTH PAW SALOON ROCK N' ROLL Baton Rouge, La. Shreveport. La. New Orleans Lalaye"e, La. 13 14 15 16 17 18 THE OLE MAN SPECTRUM RIVER'S ThibOdaux, La. New Orleans 20 21 22 23 24 25 THE LAST CLUB THIRD HAMMOND PERFORMANCE SAINT DIMENSION SOCIAL CLUB OLE MAN CRt STOPHER'S Baton Rouge, La. Hammond, La. RIVER'S New Orleans New Orleans 27 29 30 1 2 WEST COAST TOUR BEGINS Barry Mendelson presents Features Whalls Success? __________________6 In Concert Jimmy Cliff ____________________., Kid Thomas 12 Deacon John 15 ~ Disc Wars 18 Fri. April 3 Jazz Fest Schedule ---------------~3 6 Pe~er, Paul Departments April "Mary 4 ....-~- ~ 2 Rock 5 Rhylhm & Blues ___________________ 7 Rare Records 8 ~~ 9 ~k~ 1 Las/ Page _ 8 Cover illustration by Rick Spain ......,, Polrick Berry. Edllor, Connie Atkinson. -

Newsletternewsletter March 2015

NEWSLETTERNEWSLETTER MARCH 2015 HOWARD ALDEN DIGITAL RELEASES NOT CURRENTLY AVAILABLE ON CD PCD-7053-DR PCD-7155-DR PCD-7025-DR BILL WATROUS BILL WATROUS DON FRIEDMAN CORONARY TROMBOSSA! ROARING BACK INTO JAZZ DANCING NEW YORK ACD-345-DR BCD-121-DR BCD-102-DR CASSANDRA WILSON ARMAND HUG & HIS JOHNNY WIGGS MOONGLOW NEW ORLEANS DIXIELANDERS PCD-7159-DR ACD-346-DR DANNY STILES & BILL WATROUS CLIFFF “UKELELE IKE” EDWARDS IN TANDEM INTO THE ’80s HOME ON THE RANGE AVAilable ON AMAZON, iTUNES, SPOTIFY... GHB JAZZ FOUNDATION 1206 Decatur Street New Orleans, LA 70116 phone: (504) 525-5000 fax: (504) 525-1776 email: [email protected] website: jazzology.com office manager: Lars Edegran assistant: Jamie Wight office hours: Mon-Fri 11am – 5pm entrance: 61 French Market Place newsletter editor: Paige VanVorst contributors: Jon Pult and Trevor Richards HOW TO ORDER Costs – U.S. and Foreign MEMBERSHIP If you wish to become a member of the Collector’s Record Club, please mail a check in the amount of $5.00 payable to the GHB JAZZ FOUNDATION. You will then receive your membership card by return mail or with your order. As a member of the Collector’s Club you will regularly receive our Jazzology Newsletter. Also you will be able to buy our products at a discounted price – CDs for $13.00, DVDs $24.95 and books $34.95. Membership continues as long as you order one selection per year. NON-MEMBERS For non-members our prices are – CDs $15.98, DVDs $29.95 and books $39.95. MAILING AND POSTAGE CHARGES DOMESTIC There is a flat rate of $3.00 regardless of the number of items ordered. -

![Was Named Rosimore [Spelling?] John Frazier. Jfts Father Had](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0840/was-named-rosimore-spelling-john-frazier-jfts-father-had-940840.webp)

Was Named Rosimore [Spelling?] John Frazier. Jfts Father Had

J05IAH )tCIEn FRAZIER Also present: William ^ussel-l I [of 2]--Digest"-Retyped Ralph Collins December 1^., I960 Recorded at:20l4 Onzaga Street New Orleans Josiah "Cie" Frazier was born February 23, 1904. The Frazlers >, are related to t^e (Emile and Paul) Barnes and the (John, Simon, Lawrence and Eddie) Marreros; ,t^e mother of the Barnes was JFT s I father's sister, and the mother of the Marreros was also the /' sister of JF's father. JF's father played guitar years ago, i n St. Bernard Parish; his occupation was mattress making, the same / as that of Emile Barnes. JFf3 oldest brother, Sam Prazier^ once was a drummer (lives at 1717 Forstall Street); Alec Frazier (died in 1949), another brother, was a piano player, who gave a start to pianist Dave Williams, and to a "cousin" of JF, Mitchel Frazier (youngest brother of JF's father). Dave WilliamsTs mother is a cousin of JF's mother. Williams was in the [Barnes-Marrero] Band of last year, which went to Cincinnati. His [Williams^s] mother*s father was JF^s fathers brother. His [Willlams^s grandfather?] was named Rosimore [spelling?] John Frazier. JFTs father had two brothers-Michel [Mitchel?] Frazier and John Frazier--and tw 0 sisters-Kafherine Frazier and Jeannette Frazier; Je annette was the mother of the Marreros. JF1s father was named Samson Frankli n Frazier; Rosimore John was oldest, Samson Franklin the second and Mlchel was the youngest of the brothers. Mitchel dl^d about ten years ago. A younger brother of JF, Simon Frazier, who li ves in the t 2500 block of Dumalne, also learned piano from Ales Frazi er. -

New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Foundation

New Orleans' Welcome to Jazz country, where Maison Blanche our heartbeat is a down beat and salutes the the sounds of music fill the air . Welcome to Maison Blanche coun• New Orleans Jazz try, where you are the one who calls the tune and fashion is our and Heritage daily fare. Festival 70 maison blanche NEW ORLEANS Schedule WEDNESDAY - APRIL 22 8 p.m. Mississippi River Jazz Cruise on the Steamer President. Pete Fountain and his Orchestra; Clyde Kerr and his Orchestra THURSDAY - APRIL 23 12:00 Noon Eureka Brass Band 12:20 p.m. New Orleans Potpourri—Harry Souchon, M.C. Armand Hug, Raymond Burke, Sherwood Mangiapane, George Finola, Dick Johnson Last Straws 3:00 p.m. The Musical World of French Louisiana- Dick Allen and Revon Reed, M. C.'s Adam Landreneau, Cyprien Landreneau, Savy Augustine, Sady Courville, Jerry Deville, Bois Sec and sons, Ambrose Thibodaux. Clifton Chenier's Band The Creole Jazz Band with Dede Pierce, Homer Eugene, Cie Frazier, Albert Walters, Eddie Dawson, Cornbread Thomas. Creole Fiesta Association singers and dancers. At the same time outside in Beauregard Square—for the same $3 admission price— you'll have the opportunity to explore a variety of muical experiences, folklore exhibits, the art of New Orleans and the great food of South Louisiana. There will be four stages of music: Blues, Cajun, Gospel and Street. The following artists will appear throughout the Festival at various times on the stages: Blues Stage—Fird "Snooks" Eaglin, Clancy "Blues Boy" Lewis, Percy Randolph, Smilin Joe, Roosevelt Sykes, Willie B. Thomas, and others. -

Dr. Michael White: Biography

DR. MICHAEL WHITE: BIOGRAPHY Dr. Michael White is among the most visible and important New Orleans musicians today. He is one of only a few of today’s native New Orleans born artists to continue the authentic traditional jazz style. Dr. White is noted for his classic New Orleans jazz clarinet sound, for leading several popular bands, and for his many efforts to preserve and extend the early jazz tradition. Dr. White is a relative of early generation jazz musicians, including bassist Papa John Joseph, clarinetist Willie Joseph, and saxophonist and clarinetist Earl Fouche. White played in St Augustine High School’s acclaimed Marching 100 and Symphonic bands and had several years of private clarinet lessons from the band’s director, Edwin Hampton. He finished magna cum laude from Xavier University of Louisiana with a degree in foreign language education. He received a masters and a doctorate in Spanish from Tulane University. White began teaching Spanish at Xavier University in 1980 and also African American Music History since 1987. Since 2001 he has held the Charles and Rosa Keller Endowed Chair in the Humanities at Xavier. He is the founding director of Xavier’s Culture of New Orleans Series, which highlights the city’s unique culture in programs that combine scholars, authentic practitioners, and live performances. White is also a jazz historian, producer, lecturer, and consultant. He has developed and performed many jazz history themed programs. He has written and published numerous essays in books, journals, and other publications. For the last several years he has been a guest coach at the Juilliard Music School (Juilliard Jazz). -

A Researcher's View on New Orleans Jazz History

2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 6 Format 6 New Orleans Jazz 7 Brass & String Bands 8 Ragtime 11 Combining Influences 12 Party Atmosphere 12 Dance Music 13 History-Jazz Museum 15 Index of Jazz Museum 17 Instruments First Room 19 Mural - First Room 20 People and Places 21 Cigar maker, Fireman 21 Physician, Blacksmith 21 New Orleans City Map 22 The People Uptown, Downtown, 23 Lakefront, Carrollton 23 The Places: 24 Advertisement 25 Music on the Lake 26 Bandstand at Spanish Fort 26 Smokey Mary 26 Milneburg 27 Spanish Fort Amusement Park 28 Superior Orchestra 28 Rhythm Kings 28 "Sharkey" Bonano 30 Fate Marable's Orchestra 31 Louis Armstrong 31 Buddy Bolden 32 Jack Laine's Band 32 Jelly Roll Morton's Band 33 Music In The Streets 33 Black Influences 35 Congo Square 36 Spirituals 38 Spasm Bands 40 Minstrels 42 Dance Orchestras 49 Dance Halls 50 Dance and Jazz 51 3 Musical Melting Pot-Cotton CentennialExposition 53 Mexican Band 54 Louisiana Day-Exposition 55 Spanish American War 55 Edison Phonograph 57 Jazz Chart Text 58 Jazz Research 60 Jazz Chart (between 56-57) Gottschalk 61 Opera 63 French Opera House 64 Rag 68 Stomps 71 Marching Bands 72 Robichaux, John 77 Laine, "Papa" Jack 80 Storyville 82 Morton, Jelly Roll 86 Bolden, Buddy 88 What is Jazz? 91 Jazz Interpretation 92 Jazz Improvising 93 Syncopation 97 What is Jazz Chart 97 Keeping the Rhythm 99 Banjo 100 Violin 100 Time Keepers 101 String Bass 101 Heartbeat of the Band 102 Voice of Band (trb.,cornet) 104 Filling In Front Line (cl. -

New Orleans' Sweet Emma Barrett and Her Preservation Hall Jazz Band

“New Orleans' Sweet Emma Barrett and her Preservation Hall Jazz Band”--Sweet Emma and her Preservation Hall Jazz Band (1964) Added to the National Registry: 2014 Essay by Sammy Stein (guest post)* Sweet Emma Emma Barrett started playing piano aged seven and by 1910, aged just 12, she was performing regularly in bars and clubs in New Orleans. She had a strident, barrelhouse way of playing and quickly became a popular musician. Her penchant for wearing a red woven cap and garters with Christmas bells attached which jingled their accompaniment to the music, earned her the nickname of “Bell Gal.” She was also dubbed “Sweet” because of her artistic temperament apparently. Before forming her own band, Barrett played with Oscar “Papa” Celestin's Original Tuxedo Orchestra from 1923-1928 and, when that band split into two parts, Emma stayed with William “Bebe” Ridgley in his Tuxedo Jazz Orchestra until the mid 1930s when she began performing with trumpeter Sidney Desvigne, violinist player Armand Piron and bandleader, drummer and violinist John Robichaux. After a break from 1938 until 1947, Emma returned to music, playing at the Happy Landing Club in Pecaniere, which led to a renewed interest in her. In the late 1950s, after working with trumpeter Percy Humphrey and Israel Gordon, Barrett formed a band with Percy and his brother Willie, a clarinet player. In the 1960s, Barrett assembled and toured with New Orleans musicians in an ensemble called Sweet Emma and The Bells. She also recorded a live session at the Laura Lea Guest House on Mardi Gras in 1960 with her band: “Sweet Emma Barrett and her Dixieland Boys: Mardi Gras 1960.” It was not released until 1997 on 504 Records. -

Various New Orleans: the Living Legends Mp3, Flac, Wma

Various New Orleans: The Living Legends mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: New Orleans: The Living Legends Country: US Released: 1961 Style: Dixieland MP3 version RAR size: 1789 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1983 mb WMA version RAR size: 1300 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 742 Other Formats: DTS AU WAV DMF MP4 WMA AC3 Tracklist Hide Credits St. Louis Blues –"Sweet Emma" Barrett Bass – McNeal BreauxClarinet – Willie HumphreyDrums – Josiah A1 5:00 And Her Dixieland Boys Fraiser*Guitar – Emanuel SaylesPiano, Vocals – Emma BarrettTrombone – Jim Robinson Trumpet – Percy Humphrey Take My Hand, Precious Lord Banjo – "Creole George" Guesnon*Bass – Alcide (Slow Drag) –Jim Robinson's New A2 PavageauClarinet – Louis Cottrell*Drums – Alfred 2:54 Orleans Band WilliamsTrombone – Jim Robinson Trumpet – Ernest CagnolattiVocals – Annie Pavageau* I Shall Walk Through The Streets Of The City –Percy Humphrey's Banjo – Emanuel SaylesBass – Louis JamesClarinet – Albert A3 Crescent City 3:18 BurbankDrums – Josiah Fraiser*Trombone – Louis Nelson Joymakers* Trumpet – Percy Humphrey Billie's Gumbo Blues A4 –Billie & De De Pierce 3:24 Cornet – De De PierceDrums – Albert JilesPiano – Billie Pierce Mack The Knife –Kid Thomas And His Banjo – Homer EugeneBass – Joseph ButlerClarinet – Albert A5 4:36 Algiers Stompers BurbankDrums – Samuel Penn*Piano – Joe James Trombone – Louis Nelson Trumpet – Kid Thomas* Yearning –Jim Robinson's New Banjo – "Creole George" Guesnon*Bass – Alcide (Slow Drag) B1 3:52 Orleans Band PavageauClarinet – Louis Cottrell*Drums – -

A Feminist Perspective on New Orleans Jazzwomen

A FEMINIST PERSPECTIVE ON NEW ORLEANS JAZZWOMEN Sherrie Tucker Principal Investigator Submitted by Center for Research University of Kansas 2385 Irving Hill Road Lawrence, KS 66045-7563 September 30, 2004 In Partial Fulfillment of #P5705010381 Submitted to New Orleans Jazz National Historical Park National Park Service 419 Rue Decatur New Orleans, LA 70130 This is a study of women in New Orleans jazz, contracted by the National Park Service, completed between 2001 and 2004. Women have participated in numerous ways, and in a variety of complex cultural contexts, throughout the history of jazz in New Orleans. While we do see traces of women’s participation in extant New Orleans jazz histories, we seldom see women presented as central to jazz culture. Therefore, they tend to appear to occupy minor or supporting roles, if they appear at all. This Research Study uses a feminist perspective to increase our knowledge of women and gender in New Orleans jazz history, roughly between 1880 and 1980, with an emphasis on the earlier years. A Feminist Perspective on New Orleans Jazzwomen: A NOJNHP Research Study by Sherrie Tucker, University of Kansas New Orleans Jazz National Historical Park Research Study A Feminist Perspective on New Orleans Jazz Women Sherrie Tucker, University of Kansas September 30, 2004 Table of Contents Acknowledgments ................................................................................................ iii Introduction ...........................................................................................................1 -

Third Annual New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival

lOLMES HOLMES ORIGINAL STORE 1842 As traditional as New Orleans jazz, Creole cooking or southern hospitality, D. H. Holmes has been part of the beat of New Orleans since 1842. We're New Orleans' own honne-owned department store, right on the edge of the French Quarter. While in New Orleans we invite you to join an old tradition in New Orleans . arrange to meet your friends "under the clock" at Holmes ... to shop ... or to lunch or dine in our famous Creole restau• rant. In our record department you'll find one of the finest selections of true New Orleans Dixieland music on records. Holmes, itself proud to be a New Orleans tradition, salutes the Jazz and Heritage Festival and welcomes its international supporters to the birthplace of Jazz. Third Annual New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival HONORARY PRESIDENT MARDI-GRAS INDIAN CO-ORDINATOR Mayor Moon Landrieu Emile Dollis OFFICERS SECRETARIES Arthur Q. Davis, President Virginia Broussard, Suzanne Broussard Lester E. Kabacoff, Vice-Pres. Winston Lill, Vice-Pres. EVENING SECURITY Clarence J. Jupiter, Vice-Pres., Treasurer Jules Ursin Roy Bartlett 11, Secretary BOARD OF DIRECTORS THE HERITAGE FAIR Archie A. Casbarian, Dr. Frederick Hall, William V. Music Director - Quint Davis Madden, Larry McKinley, George Rhode 111, Charles B. Rousseve, Harry V. Souchon PROGRAM DIRECTOR Karen Helms - Book-keeper Allison Miner PRODUCER PERSONNEL George Wein Mark Duffy ASST. PRODUCER DESIGN Dino Santangelo - Curtis & Davis Architects; AO Davis, Bob Nunez DIRECTOR ' ' CONSTRUCTION Quint Davis Foster Awning; -

Collection of Jazz Articles

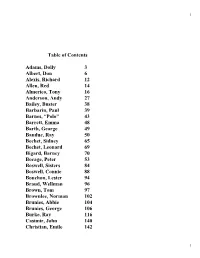

1 Table of Contents Adams, Dolly 3 Albert, Don 6 Alexis, Richard 12 Allen, Red 14 Almerico, Tony 16 Anderson, Andy 27 Bailey, Buster 38 Barbarin, Paul 39 Barnes, “Polo” 43 Barrett, Emma 48 Barth, George 49 Bauduc, Ray 50 Bechet, Sidney 65 Bechet, Leonard 69 Bigard, Barney 70 Bocage, Peter 53 Boswell, Sisters 84 Boswell, Connie 88 Bouchon, Lester 94 Braud, Wellman 96 Brown, Tom 97 Brownlee, Norman 102 Brunies, Abbie 104 Brunies, George 106 Burke, Ray 116 Casimir, John 140 Christian, Emile 142 1 2 Christian, Frank 144 Clark, Red 145 Collins, Lee 146 Charles, Hypolite 148 Cordilla, Charles 155 Cottrell, Louis 160 Cuny, Frank 162 Davis, Peter 164 DeKemel, Sam 168 DeDroit, Paul 171 DeDroit, John 176 Dejan, Harold 183 Dodds, “Baby” 215 Desvigne, Sidney 218 Dutrey, Sam 220 Edwards, Eddie 230 Foster, “Chinee” 233 Foster, “Papa” 234 Four New Orleans Clarinets 237 Arodin, Sidney 239 Fazola, Irving 241 Hall, Edmond 242 Burke, Ray 243 Frazier, “Cie” 245 French, “Papa” 256 Dolly Adams 2 3 Dolly‟s parents were Louis Douroux and Olivia Manetta Douroux. It was a musical family on both sides. Louis Douroux was a trumpet player. His brother Lawrence played trumpet and piano and brother Irving played trumpet and trombone. Placide recalled that Irving was also an arranger and practiced six hours a day. “He was one of the smoothest trombone players that ever lived. He played on the Steamer Capitol with Fats Pichon‟s Band.” Olivia played violin, cornet and piano. Dolly‟s uncle, Manuel Manetta, played and taught just about every instrument known to man. -

![For the [National] Geographic Magazine, Titled "Old Man River", Interview with Father Al Lewis P» 2 Reel I Feb](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1991/for-the-national-geographic-magazine-titled-old-man-river-interview-with-father-al-lewis-p%C2%BB-2-reel-i-feb-4581991.webp)

For the [National] Geographic Magazine, Titled "Old Man River", Interview with Father Al Lewis P» 2 Reel I Feb

Interview with Father Al Lewis Also present: Lars Edegran, Hans Reel I Lychou, Richard B. Alien Feb. 21, 1972 Digest: Marie L. Spencer Check; RBA Father Al states that his full name is Alfred Longfellow Lewis. ^ <T Today he is known as "Father Al", He was born in Terrebonne Parish/ Houma, Louisiana, August 9thj 1903 which date he says he "has just about got straight now," 12:21 FA^came to New Orleans when he was nine months old, living at St. MaryLStreetJ and Prytania [Street]. His family moved several times: to 4424 Clara [Street]^ then to 4530 S. Robertson [Street], While living there, FA,i attended Jessica Ennis's private school, 12:29 located at 2622 Jena Street. FA'jattended New Orleans University, 5318 St. Charles Street for more schooling, leaving there in the 10th grade- Later in Chicago FAliwent to [Al C. Boyd or Alcide Boyd?] school for refresher courses/ staying there about two and one half years. 12:34 Later, after moving back to New Orleans, FAl, worked in a variety of jobs- He made a few scenes for Paramount [Pictures] in Cata- A / / y houla Lake District, twenty-two miles from St, Martinsvxlle. [cf. f nt mapsl* He also played music on a steamer [under?] H.V- Cooley [Captain?], making the run from New Orleans to Camden/ Arkansas on the [steamer?] buachita. TTne band members with FA\.were; Alien -*<f" Gardette [tp?], [Wilbert] Tillman, s, and Benny Alien (p) . Martin Cole played [saxophone?] with them awhile as did [Willie E.] Humphrey (Willie J. Humphrey's daddy).