Mentha Piperita

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Separations-06-00017-V2.Pdf

separations Article Perfluoroalkyl Substance Assessment in Turin Metropolitan Area and Correlation with Potential Sources of Pollution According to the Water Safety Plan Risk Management Approach Rita Binetti 1,*, Paola Calza 2, Giovanni Costantino 1, Stefania Morgillo 1 and Dimitra Papagiannaki 1,* 1 Società Metropolitana Acque Torino S.p.A.—Centro Ricerche, Corso Unità d’Italia 235/3, 10127 Torino, Italy; [email protected] (G.C.); [email protected] (S.M.) 2 Università di Torino, Dipartimento di Chimica, Via Pietro Giuria 5, 10125 Torino, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondences: [email protected] (R.B.); [email protected] (D.P.); Tel.: +39-3275642411 (D.P.) Received: 14 December 2018; Accepted: 28 February 2019; Published: 19 March 2019 Abstract: Per and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) are a huge class of Contaminants of Emerging Concern, well-known to be persistent, bioaccumulative and toxic. They have been detected in different environmental matrices, in wildlife and even in humans, with drinking water being considered as the main exposure route. Therefore, the present study focused on the estimation of PFAS in the Metropolitan Area of Turin, where SMAT (Società Metropolitana Acque Torino S.p.A.) is in charge of the management of the water cycle and the development of a tool for supporting “smart” water quality monitoring programs to address emerging pollutants’ assessments using multivariate spatial and statistical analysis tools. A new “green” analytical method was developed and validated in order to determine 16 different PFAS in drinking water with a direct injection to the Ultra High Performance Liquid Chromatography tandem Mass Spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS) system and without any pretreatment step. -

Trofeo Esordienti Provinciale Girone "A" Comitato Regionale

Comitato Regionale Piemontese - Settore Minibasket & Scuola [email protected] ; [email protected] Trofeo Esordienti Provinciale Girone "A" Trofeo Casa Trasferta Data e Giorno Risultato Eso M. Prov MINIBASKET CIRIE' C.M. RIVER BORGARO 39 - 27 412 Eso M. Prov USAC MINIBASKET ETEILA BASKET 18 - 19 413 Eso M. Prov A.S.D. SEA BASKET SETTIMO ASD LETTERA 22 IVREA 0 414 Eso M. Prov C.M. RIVER BORGARO POL. SARRE/CHESALLET 16 - 66 415 Eso M. Prov ETEILA BASKET MINIBASKET CIRIE' 56 - 10 416 Eso M. Prov ASD LETTERA 22 IVREA USAC MINIBASKET 0 417 Eso M. Prov ETEILA BASKET C.M. RIVER BORGARO 54 - 12 418 Eso M. Prov A.S.D. SEA BASKET SETTIMO POL. SARRE/CHESALLET 26 - 44 419 Eso M. Prov MINIBASKET CIRIE' ASD LETTERA 22 IVREA 31 - 26 420 Eso M. Prov C.M. RIVER BORGARO A.S.D. SEA BASKET SETTIMO 0 421 Eso M. Prov ASD LETTERA 22 IVREA ETEILA BASKET 33 - 36 422 Eso M. Prov POL. SARRE/CHESALLET USAC MINIBASKET 39 - 22 423 Eso M. Prov ASD LETTERA 22 IVREA C.M. RIVER BORGARO 54 - 15 424 Eso M. Prov USAC MINIBASKET A.S.D. SEA BASKET SETTIMO 13 - 45 425 Eso M. Prov MINIBASKET CIRIE' POL. SARRE/CHESALLET 13 - 45 426 Eso M. Prov C.M. RIVER BORGARO USAC MINIBASKET 0 427 Eso M. Prov A.S.D. SEA BASKET SETTIMO MINIBASKET CIRIE' 65 - 25 428 Eso M. Prov POL. SARRE/CHESALLET ETEILA BASKET 36 - 24 429 Eso M. Prov MINIBASKET CIRIE' USAC MINIBASKET 27 - 26 430 Eso M. -

One Territory, Infinite Emotions

www.turismotorino.org ONE TERRITORY, TORINO • Piazza Castello/Via Garibaldi INFINITE • Piazza Carlo Felice • International Airport (interactive totem) Contact centre +39.011.535181 [email protected] EMOTIONS. BARDONECCHIA Piazza De Gasperi 1 +39.0122.99032 [email protected] CESANA TORINESE Piazza Vittorio Amedeo 3 +39.0122.89202 [email protected] CLAVIÈRE Via Nazionale 30 +39.0122.878856 [email protected] IVREA Piazza Ottinetti +39.0125.618131 [email protected] PINEROLO Viale Giolitti 7/9 +39.0121.795589 [email protected] PRAGELATO Piazza Lantelme 2 +39.0122.741728 [email protected] SAuze d’OULX Viale Genevris 7 +39.0122.858009 [email protected] SESTRIERE Via Louset +39.0122.755444 [email protected] SUSA Corso Inghilterra 39 +39.0122.622447 [email protected] A CITY YOU City Sightseeing Torino is a valuable ally in your time spent WOULDN’T EXPECT in Torino. By means of this “panoramic” double-decker bus you will be able to discover the city’s many souls, travelling on two lines: “Torino City Centre” and If you decide to stay in Torino “Unexpected Torino”. You can’t get more or the surrounding areas for your convenient than that… holiday, our Hotel & Co. service lets www.turismotorino.org/en/citysightseeing you reserve your stay at any time directly online. Book now! ot www.turismotorino.org/en/book .turism orino.o ww rg/ w en Lively and elegant, always in movement, nonetheless Torino is incredibly a city set in the heart of verdant areas: gently resting on the hillside and enclosed by the winding course of the River Po, it owes much of its charm to its enchanting location at the foot of the western Alps, watched over by snowy peaks. -

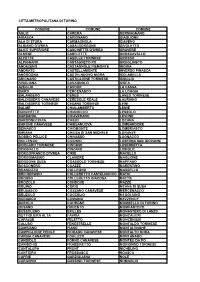

Città Metropolitana Di Torino Comune Comune Comune

CITTÀ METROPOLITANA DI TORINO COMUNE COMUNE COMUNE AGLIÈ CAREMA GERMAGNANO AIRASCA CARIGNANO GIAGLIONE ALA DI STURA CARMAGNOLA GIAVENO ALBIANO D'IVREA CASALBORGONE GIVOLETTO ALICE SUPERIORE CASCINETTE D'IVREA GRAVERE ALMESE CASELETTE GROSCAVALLO ALPETTE CASELLE TORINESE GROSSO ALPIGNANO CASTAGNETO PO GRUGLIASCO ANDEZENO CASTAGNOLE PIEMONTE INGRIA ANDRATE CASTELLAMONTE INVERSO PINASCA ANGROGNA CASTELNUOVO NIGRA ISOLABELLA ARIGNANO CASTIGLIONE TORINESE ISSIGLIO AVIGLIANA CAVAGNOLO IVREA AZEGLIO CAVOUR LA CASSA BAIRO CERCENASCO LA LOGGIA BALANGERO CERES LANZO TORINESE BALDISSERO CANAVESE CERESOLE REALE LAURIANO BALDISSERO TORINESE CESANA TORINESE LEINÌ BALME CHIALAMBERTO LEMIE BANCHETTE CHIANOCCO LESSOLO BARBANIA CHIAVERANO LEVONE BARDONECCHIA CHIERI LOCANA BARONE CANAVESE CHIESANUOVA LOMBARDORE BEINASCO CHIOMONTE LOMBRIASCO BIBIANA CHIUSA DI SAN MICHELE LORANZÈ BOBBIO PELLICE CHIVASSO LUGNACCO BOLLENGO CICONIO LUSERNA SAN GIOVANNI BORGARO TORINESE CINTANO LUSERNETTA BORGIALLO CINZANO LUSIGLIÈ BORGOFRANCO D'IVREA CIRIÈ MACELLO BORGOMASINO CLAVIERE MAGLIONE BORGONE SUSA COASSOLO TORINESE MAPPANO BOSCONERO COAZZE MARENTINO BRANDIZZO COLLEGNO MASSELLO BRICHERASIO COLLERETTO CASTELNUOVO MATHI BROSSO COLLERETTO GIACOSA MATTIE BROZOLO CONDOVE MAZZÈ BRUINO CORIO MEANA DI SUSA BRUSASCO COSSANO CANAVESE MERCENASCO BRUZOLO CUCEGLIO MEUGLIANO BURIASCO CUMIANA MEZZENILE BUROLO CUORGNÈ MOMBELLO DI TORINO BUSANO DRUENTO MOMPANTERO BUSSOLENO EXILLES MONASTERO DI LANZO BUTTIGLIERA ALTA FAVRIA MONCALIERI CAFASSE FELETTO MONCENISIO CALUSO FENESTRELLE MONTALDO -

Orario Pancalieri 01 01 2015

Linea 260/1 Pancalieri Torino e diramazioni orari in vigore dal 01 gennaio 2015 n° corsa 202 204 206 208 210 212 214 216 218 220 222 224 226 228 230 232 234 236 238 240 Vedi nota 1 1 2 2 1 Giorni Festivi ■ ■ ■ Al Sabato ♦ ♦ ♦ ♣ ♦ ♦ ♦ ■ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ■ Lunedì venerdì ♦ ♦ ▲ ▲ ♦ ▲♣ ▲ ♦ ♦ ♦ ■ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ■ ▲ ♦ Pancalieri 4:50 5:40 6:20 6:35 6:50 7:05 7:20 7:50 8:50 10:50 11:50 12:45 13:20 13:50 14:50 15:50 16:50 17:50 18:50 20:50 Virle 4:55 5:45 6:25 6:40 6:55 7:10 7:25 7:55 8:55 10:55 11:55 12:50 13:25 13:55 14:55 15:55 16:55 17:55 18:55 20:55 Castagnole 5:01 5:51 6:31 6:46 7:01 7:16 7:31 8:01 9:01 11:01 12:01 12:56 13:30 14:01 15:01 16:01 17:01 18:01 19:01 21:01 None 5:10 6:00 6:40 6:55 7:10 7:25 7:40 8:10 9:10 11:10 12:10 13:05 13:39 14:10 15:10 16:10 17:10 18:10 19:10 21:10 None stab.Indesit 5:14 6:04 6:44 6:59 7:14 7:29 7:44 8:14 9:14 11:14 12:14 13:09 13:45 14:14 15:14 16:14 17:14 18:14 19:14 21:14 Gli orari indicati si riferiscono al transito in centro Candiolo Soff.Bert. -

Uffici Locali Dell'agenzia Delle Entrate E Competenza

TORINO Le funzioni operative dell'Agenzia delle Entrate sono svolte dalle: Direzione Provinciale I di TORINO articolata in un Ufficio Controlli, un Ufficio Legale e negli uffici territoriali di MONCALIERI , PINEROLO , TORINO - Atti pubblici, successioni e rimborsi Iva , TORINO 1 , TORINO 3 Direzione Provinciale II di TORINO articolata in un Ufficio Controlli, un Ufficio Legale e negli uffici territoriali di CHIVASSO , CIRIE' , CUORGNE' , IVREA , RIVOLI , SUSA , TORINO - Atti pubblici, successioni e rimborsi Iva , TORINO 2 , TORINO 4 La visualizzazione della mappa dell'ufficio richiede il supporto del linguaggio Javascript. Direzione Provinciale I di TORINO Comune: TORINO Indirizzo: CORSO BOLZANO, 30 CAP: 10121 Telefono: 01119469111 Fax: 01119469272 E-mail: [email protected] PEC: [email protected] Codice Ufficio: T7D Competenza territoriale: Circoscrizioni di Torino: 1, 2, 3, 8, 9, 10. Comuni: Airasca, Andezeno, Angrogna, Arignano, Baldissero Torinese, Bibiana, Bobbio Pellice, Bricherasio, Buriasco, Cambiano, Campiglione Fenile, Cantalupa, Carignano, Carmagnola, Castagnole Piemonte, Cavour, Cercenasco, Chieri, Cumiana, Fenestrelle, Frossasco, Garzigliana, Inverso Pinasca, Isolabella, La Loggia, Lombriasco, Luserna San Giovanni, Lusernetta, Macello, Marentino, Massello, Mombello di Torino, Moncalieri, Montaldo Torinese, Moriondo Torinese, Nichelino, None, Osasco, Osasio, Pancalieri, Pavarolo, Pecetto Torinese, Perosa Argentina, Perrero, Pinasca, Pinerolo, Pino Torinese, Piobesi Torinese, Piscina, Poirino, Pomaretto, -

Linea 299V Saluzzo - Villafranca Piemonte Tpl Extraurbano Linea 299T Villafranca Piemonte - Torino Citta' Metropolitana Di Torino

LINEA 299V SALUZZO - VILLAFRANCA PIEMONTE TPL EXTRAURBANO LINEA 299T VILLAFRANCA PIEMONTE - TORINO CITTA' METROPOLITANA DI TORINO IN VIGORE DAL 13 SETTEMBRE 2021 299V SALUZZO > VILLAFRANCA PIEMONTE CORSA 1 19 37 55 73 85 97 109 121 139 151 163 169 181 193 205 217 229 DOMENICA E FESTIVI INFRASETTIMANALI ■ ■ ■ ■ SABATO ❏ -2A ❏ -2A ■ ❏ -2A ❏ -2A ■ ❏ -2A ❏ -2A ■ ❏ -2A ❏ -2A ❏ -2A ■ ❏ -2A ❏ -2A DA LUNEDÌ A VENERDÌ ❏ -2A ❏ -2A ■ ❏ -4A ❏ -2A ❏ -4A ❏ -2A ■ ❏ -2A ❏ -2A ■ x ❏ -2A ❏ -2A ❏ -2A ■ ❏ -2A ❏ -2A N. fer NOTA 1 6 6 6160 SALUZZO / Stazione FS 13.55 1 SALUZZO / Autostazione 05.40 06.15 06.55 07.25 07.55 08.25 09.25 11.25 12.35 13.05 14.03 14.00 15.05 16.25 17.25 18.25 20.15 6163 SALUZZO / S. Agostino 13.06 14.04 14.01 16.26 17.26 6062 CARDE' / Corso Vittorio Emanuele II 04.25 05.50 06.25 07.05 07.35 08.05 08.35 09.35 11.35 12.45 13.18 14.16 14.13 15.15 16.38 17.38 18.35 20.25 6064 VILLAFRANCA / Scuole (arrivo) 04.33 05.59 06.34 07.14 07.44 08.14 08.44 09.44 11.45 12.54 13.27 14.24 14.22 15.24 16.47 17.47 18.44 20.33 299T VILLAFRANCA PIEMONTE > TORINO CORSA 7 9 13 260103 25 31 43 49 61 67 79 91 103 115 127 133 145 157 163 175 187 199 211 223 235 229 DOMENICA E FESTIVI INFRASETTIMANALI ■ ■ ■ ■ SABATO ❏ -2A ❏ -2A ❏ -2A ■ ❏ -2A ❏ -2A ■ ❏ -4A ❏ -2A ■ ❏ -2A ❏ -2A ❏ -2A ■ ❏ -2A ❏ -2A DA LUNEDÌ A VENERDÌ ❏ -2A ❏ -4A ❏ -4A ❏ -2A ❏ -2A ❏ -4A ■ ❏ -4A ❏ -4A ❏ -2A ❏ -2A ❏ -4A ❏ -2A ■ ❏ -4A ❏ -4A ❏ -2A ■ x ❏ -2A ❏ -2A ❏ -2A ■ ❏ -2A ❏ -2A ❏ -2A N. -

Elenco Dei Comuni Inseriti Nelle Zone Omogenee Della Citta

ELENCO DEI COMUNI INSERITI NELLE ZONE OMOGENEE DELLA CITTA’ METROPOLITANA DI TORINO (hp://www.ciametropolitana.torino.it/cms/territorio-urbanistica/ pianificazione-strategica/zone-omogenee) Zona 1 “TORINO” (N. Comuni 1: Torino) Zona 2 “AMT OVEST” (N. Comuni 14: Alpignano, Buigliera Alta, Collegno, Druento, Grugliasco, Piane a, Reano, Rivoli, Rosta, San Gillio, Sangano, Trana, Venaria, Villarbasse) Zona 3 “AMT SUD” (N. Comuni 18: Beinasco, Bruino, Candiolo, Carignano, Castagnole P.te, La Loggia, Moncalieri, Nichelino, None, Orbassano, Pancalieri, Piossasco, Piobesi Torinese, Rivalta di Torino, Trofarello, Vinovo, Virle Piemonte,Volvera) Zona 4 “AMT NORD” (N. Comuni 7: Borgaro Torinese, Caselle Torinese, Lein., San Benigno C.se, San Mauro Torinese, Seimo Torinese, Volpiano) Zona 5 “PINEROLESE” (N. Comuni 45: Airasca, Angrogna, Bibiana, Bobbio Pellice, Bricherasio, Buriasco, Campiglione 0enile, Cantalupa, Cavour, Cercenasco, Cumiana, 0enestrelle, 0rossasco, Gar igliana, 1nverso Pinasca, Luserna S. Giovanni, Lusernea, Macello, Massello, Osasco, Perosa Argentina, Perrero, Pinasca, Pinerolo, Piscina, Pomareo, Porte, Pragelato, Prali, Pramollo, Prarostino, Roleo, Ror2, Roure, Sal a di Pinerolo, San Germano C.se, San Pietro Val Lemina, San Secondo di P., Scalenghe, Torre Pellice, 3sseau4, Vigone, Villafranca Piemonte, Villar Pellice, Villar Perosa) Zona 6 “VALLI SUSA E SANGONE” (N. Comuni 40: Almese, Avigliana, Bardonecchia, Borgone Susa, Bru olo, Bussoleno, Caprie, Caselee, Cesana T.se, Chianocco, Chiomonte, Chiusa di San Michele, Claviere, Coa e, Condove, E4illes, Giaglione, Giaveno, Gravere, Maie, Meana di Susa, Mompantero, Moncenisio, Novalesa, Oul4, Rubiana, Salbertrand, San Didero, San Giorio di Susa, Sant7Ambrogio di Torino, Sant7Antonino di Susa, Sau e di Cesana, Sau e d7Oul4, Sestriere, Susa, Vaie, Valgioie, Venaus, Villar Dora, Villarfocchiardo) Zona 7 “CIRIACESE - VALLI DI LANZO” (N. -

Il Vademecum Per Il Pescatore

Versione aggiornata al 30/06/2021 (ulteriori aggiornamenti saranno pubblicati appena disponibili) SOMMARIO SOMMARIO............................................................................................2 FONTI NORMATIVE.................................................................................3 CLASSIFICAZIONE DELLE ACQUE.............................................................4 PRINCIPALI MODALITÀ VIETATE IN TUTTE LE ACQUE SUPERFICIALI.............5 ACQUE SALMONICOLE............................................................................6 DIRITTI DEMANIALI ESCLUSIVI DI PESCA (D.D.E.P.)................................8 ALTRE ACQUE SOGGETTE A PARTICOLARI DIRITTI O CONCESSIONI...........11 ACQUE DATE IN CONCESSIONE PER PESCA TURISTICA E NO-KILL............12 CONSEGUIMENTO E RINNOVO DELLA LICENZA DI PESCA..........................13 ORARI................................................................................................16 POSTO DI PESCA E DISTANZA DEGLI ATTREZZI.......................................16 ATTREZZI E MODALITÀ DI PESCA...........................................................16 SPECIE, PERIODI CHIUSURA, MISURE MINIME, LIMITI GIORNALIERI DI CATTURA PER LA PESCA DELLA FAUNA ITTICA NELLA CITTÀ METROPOLITANA DI TORINO..................................................................17 SPECIE DI FAUNA ACQUATICA PER LE QUALI VIGE IL DIVIETO DI PESCA....23 SPECIE DI FAUNA ITTICA CHE POSSONO ESSERE PESCATE, NELLE ACQUE CIPRINICOLE, SENZA LIMITAZIONI DI PERIODI, MISURE O QUANTITATIVO (ALLEGATO “C” DPGR -

Dipartimenti Di Prevenzione Delle ASL Della Regione Piemonte Ambito Territoriale (Comuni)

Dipartimenti di prevenzione delle ASL della Regione Piemonte Ambito territoriale (comuni) 1 ASL Ambito territoriale ASL Città di Torino Torino Almese, Avigliana, Bardonecchia, Beinasco, Borgone Susa, Bruino, Bruzolo, Bussoleno, Buttigliera Alta, Caprie, Caselette, Cesana Torinese, Chianocco, Chiomonte, Chiusa di San Michele, Claviere, Coazze, Collegno, Condove, Exilles, Giaglione, Giaveno, Gravere, Grugliasco, Mattie, Meana di Susa, Mompantero, Moncenisio, Novalesa, Orbassano, Oulx, Piossasco, Reano, Rivalta di Torino, Rivoli, Rosta, Rubiana, Salbertrand, San Didero, San Giorio di Susa, Sangano, Sant’ambrogio di Torino, Sant’Antonino di Susa, Sauze di Cesana, Sauze d’Oulx, Susa, Trana, Vaie, Valgioie, Venaus, Villar Dora, Villar Focchiardo, Villarbasse, Volvera, Alpignano, Druento, ASL TO3 Givoletto, La Cassa, Pianezza, San Gillio, Val della Torre, Venaria Reale, Airasca, Angrogna, Bibiana, Bobbio Pellice, Bricherasio, Buriasco, Campiglione Fenile, Cantalupa, Cavour, Cercenasco, Cumiana, Fenestrelle, Frossasco, Garzigliana, Inverso Pinasca, Luserna San Giovanni, Lusernetta, Macello, Massello, Osasco, Perosa Argentina, Perrero, Pinasca, Pinerolo, Piscina, Pomaretto, Porte, Pragelato, Prali, Pramollo, Prarostino, Roletto, Rorà, Roure, Salza di Pinerolo, San Germano Chisone, San Pietro Val Lemina, San Secondo di Pinerolo, Scalenghe, Sestriere, Torre Pellice, Usseaux, Vigone, Villafranca Piemonte, Villar Pellice, Villar Perosa, Virle Piemonte. Ala di Stura, Balangero, Balme, Barbania, Borgaro Torinese, Cafasse, Cantoira, Caselle Torinese, -

Cumiana Percorsi E Orari Autobus As 2018/2019

SCUOLA MEDIA "DON BOSCO" CUMIANA PERCORSI E ORARI AUTOBUS A.S. 2018/2019 Linea 1 Top class 08 7:15 ORBASSANO 16 VIA GOZZANO, STRADA TORINO, VIA DI NANNI, VIA CIRCONVALAZIONE INTERNA, VIA FREJUS , STRADA PIOSSASCO. 7:25 PRABERNASCA (piramid) 8 VIA GIAVENO 7:30 BRUINO 4 VIA ORBASSANO, VIA TORINO, VIA PIOSSASCO 7:40 PIOSSASCO 18 VIA SUSA, VIA TORINO, VIA PINEROLO 46 Linea 2 EUROCLASS 48 7:05 CANDIOLO 4 VIA CARDUCCI, VIA PIO V 7:15 NONE VIA TORINO, VIA CASTAGNOLE, 7:20 CASTAGNOLE P.TE 10 VIA TORINO, VIA VERDI, PIAZZA VITT. EMANUELE II, VIA ROMA, VIA MARCONI, CIRCONVALAZIONE 7:30 NONE 14 VIA P. ANGELICO,VIA FAUNASCO, VIA SCALENGHE, VIA VOLVERA, VIA SANTAROSA 7:45 AIRASCA 5 VIA ROMA 7:50 BIVIO BOTTEGHE 2 7:55 PISCINA 2 VIA UMBERTO I, VIA AIRASCA Linea 3 EUROCLASS 52 7:25 VOLVERA 38 VIA AIRASCA, PIAZZA CAVOUR, VIA XXIV MAGGIO, VIA PIAVE, VIA ORBASSANO 7:35 GERBOLE 8 STRADA ORBASSANO 7:50 CUMIANA 12 PIAZZA MARTIRI III APRILE, VIA BOSELLI, STRADA PROVINCIALE 146 58 Linea 4 Top class 09 7:20 RIVA DI PINEROLO VIA MAESTRA RIVA, CORSO TORINO 7:25 PINEROLO 11 CORSO TORINO, PIAZZA GARIBALDI ( STAZ. FF.SS.), VIA MARTIRI DEL XXI, STR. ORBASSANO 7:35 ROLETTO 4 VIA ROMA, VIA FROSSASCO 7:40 CANTALUPA 7 VIA ROMA 7:45 FROSSASCO 4 VIA PRINCIPE AMEDEO 26 Linea 5 Ducato 7:20 CERCENASCO 7 VIA PAVESE, VIA REGINA MARGHERITA, VIA ROMA, VIA XX SETTEMBRE. 7:25 SCALENGHE 1 Linea 6 Scudo 7:30 VIGONE 6 VIA PANCALIERI, VIA VITTORIO VENETO, VIA MONS. -

Piemonte Torino

DISPONIBILITÀ comunali di SPAZI per AFFISSIONI PROVINCIA COMUNE ABITANTI POSTER 6X3 100X140 70X100 TORINO Agliè 2'591 --- 10 10 TORINO Airasca 3'808 --- 10 10 TORINO Ala di Stura 465 --- 5 5 TORINO Albiano d'Ivrea 1'778 --- 10 10 TORINO Alice Superiore 713 --- 5 5 TORINO Almese 6'378 --- 15 15 TORINO Alpette 271 --- 5 5 TORINO Alpignano 17'097 1 30 30 TORINO Andezeno 2'010 --- 10 10 TORINO Andrate 521 --- 5 5 TORINO Angrogna 882 --- 5 5 TORINO Arignano 1'057 --- 10 10 TORINO Avigliana 12'367 1 30 30 TORINO Azeglio 1'375 --- 10 10 TORINO Bairo 819 --- 5 5 TORINO Balangero 3'178 --- 10 10 TORINO Baldissero Canavese 551 --- 5 5 TORINO Baldissero Torinese 3'825 --- 10 10 TORINO Balme 97 --- 5 5 TORINO Banchette 3'355 --- 10 10 TORINO Barbania 1'632 --- 10 10 TORINO Bardonecchia 3'273 --- 10 10 TORINO Barone Canavese 597 --- 5 5 TORINO Beinasco 18'185 1 30 30 TORINO Bibiana 3'399 --- 10 10 TORINO Bobbio Pellice 566 --- 5 5 TORINO Bollengo 2'088 --- 10 10 TORINO Borgaro Torinese 13'502 1 30 30 TORINO Borgiallo 556 --- 5 5 TORINO Borgofranco d'Ivrea 3'780 --- 10 10 TORINO Borgomasino 845 --- 5 5 TORINO Borgone Susa 2'372 --- 10 10 TORINO Bosconero 3'101 --- 10 10 TORINO Brandizzo 8'297 --- 15 15 TORINO Bricherasio 4'454 --- 10 10 TORINO Brosso 472 --- 5 5 TORINO Brozolo 481 --- 5 5 TORINO Bruino 8'520 --- 15 15 TORINO Brusasco 1'760 --- 10 10 TORINO Bruzolo 1'540 --- 10 10 TORINO Buriasco 1'411 --- 10 10 TORINO Burolo 1'267 --- 10 10 TORINO Busano 1'571 --- 10 10 TORINO Bussoleno 6'521 --- 15 15 TORINO Buttigliera Alta 6'458 --- 15 15 TORINO Cafasse 3'585 --- 10 10 TORINO Caluso 7'679 --- 15 15 Due Valli Pubblicità S.r.l.