The Dramatic World of Harold Pinter: Its Basis in Ritual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Making Pictures the Pinter Screenplays

Joanne Klein Making Pictures The Pinter Screenplays MAKING PICTURES The Pinter Screenplays by Joanne Klein Making Pictures: The Pinter Screenplays Ohio State University Press: Columbus Extracts from F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Last Tycoon. Copyright 1941 Charles Scribner's Sons; copyright renewed. Reprinted with the permission of Charles Scribner's Sons. Extracts from John Fowles, The French Lieutenant's Woman. Copyright © 1969 by John Fowles. By permission of Little, Brown and Company. Extracts from Harold Pinter, The French Lieutenant's Woman: A Screenplay. Copyright © 1982 by United Artists Corporation and Copyright © 1982 by J. R. Fowles, Ltd. Extracts from L. P. Hartley, The Go-Between. Copyright © 1954 and 1981 by L. P. Hartley. Reprinted with permission of Stein and Day Publishers. Extracts from Penelope Mortimer, The Pumpkin Eater. © 1963 by Penelope Mortimer. Reprinted by permission of the Harold Matson Company, Inc. Extracts from Nicholas Mosley, Accident. Copyright © 1965 by Nicholas Mosley. Reprinted by permission of Hodder and Stoughton Limited. Copyright © 1985 by the Ohio State University Press All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Klein, Joanne, 1949 Making pictures. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Pinter, Harold, 1930- —Moving-picture plays. I. Title. PR6066.I53Z713 1985 822'.914 85-326 Cloth: ISBN 0-8142-0378-7 Paper: ISBN 0-8142-0400-7 for William I. Oliver Contents Acknowledgments ix Chronology of Pinter's Writing for Stage and Screen xi 1. Media 1 2. The Servant 9 3. The Pumpkin Eater 27 4. The Quiller Memorandum 42 5. Accident 50 6. The Go-Between 77 1. The Proust Screenplay 103 8. -

The Hothouse HAROLD PINTER

CRÉATION The Hothouse HAROLD PINTER 20 21 GRAND THÉÂTRE › STUDIO 2 CRÉATION The Hothouse HAROLD PINTER WEDNESDAY 24, THURSDAY 25, FRIDAY 26, TUESDAY 30 & WEDNESDAY 31 MARCH & THURSDAY 1 & FRIDAY 2, TUESDAY 6, WEDNESDAY 7, FRIDAY 9 & SATURDAY 10 APRIL 2021 › 8PM WEDNESDAY 7 & SATURDAY 10 APRIL 2021 › 3PM SUNDAY 11 APRIL 2021 › 5PM – Running time 2h00 (no interval) – Introduction to the play by Janine Goedert 30 minutes before every performance (EN). – This performance contains stroboscopic lights. 3 GRAND THÉÂTRE › STUDIO 4 With Tubb Pol Belardi Lamb Danny Boland Miss Cutts Céline Camara Lobb Catherine Janke Lush Marie Jung Roote Dennis Kozeluh Gibbs Daron Yates & Georges Maikel (dance) – Directed by Anne Simon Set design Anouk Schiltz Costume design Virginia Ferreira Music & sound design Pol Belardi Lighting design Marc Thein Assistant director Sally Merres Make-up Joël Seiller – Wardrobe Manuela Giacometti Props Marko Mladjenovic – Production Les Théâtres de la Ville de Luxembourg 5 GRAND THÉÂTRE › STUDIO THE HOTHOUSE The Hothouse is a play about unchecked (state)-power and the decisions leaders make – spurious decisions that are potentially dangerous in the name for the preservation of a society. Somewhere in an authoritarian state. Former military Colonel Roote runs an institution where bureaucracy rules and the inmates are reduced to numbers. When one Christmas day, the cantankerous Colonel is confronted by a double crisis with the death of one inmate and the pregnancy of another, he finds himself increasingly cornered and sees the system he obeys so respectfully slip away. The Hothouse is a blackly comic portrait of the insidious corruption of power and demonstrates how far people will go to keep a system alive that is long condemned to fail. -

Think Night: London's Neighbourhoods from 6Pm

THINK NIGHT: LONDON’S NEIGHBOURHOODS FROM 6PM TO 6AM LONDON NIGHT TIME COMMISSION FOREWORD London is a world-class city. As such, of expert witnesses. In another world-first, it merits world-leading thoughts on all we commissioned new research to hear aspects of city life at night. from Londoners themselves about how they use the city between 6pm and 6am: what We are interested in London’s identity they do, what activities they take part in and at night. When we talk about night we crucially what more needs to be done to therefore consider it as broadly as we allow them to live their lives more fully. would the day. We have used a wide lens, looking at the wealth of activities that London is a dynamic and diverse ecosystem happen from 6pm to 6am. at night that goes far beyond commercial transactions. It incorporates the culture, Uniquely, London’s Night Time Commission character and atmosphere of our city. was established to build on London’s Londoners are more active between 6pm and strengths rather than to address a crisis. 6am, and have later bedtimes and a better Our focus goes well beyond the scope of quality of sleep, than anyone else in the other similar bodies that centre only on UK. Two-thirds of us regularly do everyday the night time economy. The Commission activities at night – errands, shopping, set itself a broad, holistic framework: to catching up with friends – and a staggering develop and help realise an ambitious 1.6 million of us usually work at night. -

London at Night: an Evidence Base for a 24-Hour City

London at night: An evidence base for a 24-hour city November 2018 London at night: An evidence base for a 24-hour city copyright Greater London Authority November 2018 Published by Greater London Authority City Hall The Queens Walk London SE1 2AA www.london.gov.uk Tel 020 7983 4922 Minicom 020 7983 4000 ISBN 978-1-84781-710-5 Cover photograph © Shutterstock For more information about this publication, please contact: GLA Economics Tel 020 7983 4922 Email [email protected] GLA Economics provides expert advice and analysis on London’s economy and the economic issues facing the capital. Data and analysis from GLA Economics form a basis for the policy and investment decisions facing the Mayor of London and the GLA group. GLA Economics uses a wide range of information and data sourced from third party suppliers within its analysis and reports. GLA Economics cannot be held responsible for the accuracy or timeliness of this information and data. The GLA will not be liable for any losses suffered or liabilities incurred by a party as a result of that party relying in any way on the information contained in this report. London at night: An evidence base for a 24-hour city Contents Foreword from the Mayor of London .......................................................................................... 2 Foreword from the London Night Time Commission ................................................................... 3 Foreword from the Night Czar .................................................................................................... -

The Cambridge Companion to Harold Pinter Edited by Peter Raby Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521651239 - The Cambridge Companion to Harold Pinter Edited by Peter Raby Frontmatter More information The Cambridge Companion to Harold Pinter The Cambridge Companion to Harold Pinter provides an introduction to one of the world’s leading and most controversial writers, whose output in many genres and roles continues to grow. Harold Pinter has written for the theatre, radio, television and screen, in addition to being a highly successful director and actor. This volume examines the wide range of Pinter’s work (including his recent play Celebration). The first section of essays places his writing within the critical and theatrical context of his time, and its reception worldwide. The Companion moves on to explore issues of performance, with essays by practi- tioners and writers. The third section addresses wider themes, including Pinter as celebrity, the playwright and his critics, and the political dimensions of his work. The volume offers photographs from key productions, a chronology and bibliography. © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521651239 - The Cambridge Companion to Harold Pinter Edited by Peter Raby Frontmatter More information CAMBRIDGE COMPANIONS TO LITERATURE The Cambridge Companion to Greek Tragedy The Cambridge Companion to the French edited by P. E. Easterling Novel: from 1800 to the Present The Cambridge Companion to Old English edited by Timothy Unwin Literature The Cambridge Companion to Modernism edited by Malcolm Godden and Michael edited by Michael Levenson Lapidge The Cambridge Companion to Australian The Cambridge Companion to Medieval Literature Romance edited by Elizabeth Webby edited by Roberta L. Kreuger The Cambridge Companion to American The Cambridge Companion to Medieval Women Playwrights English Theatre edited by Brenda Murphy edited by Richard Beadle The Cambridge Companion to Modern British The Cambridge Companion to English Women Playwrights Renaissance Drama edited by Elaine Aston and Janelle Reinelt edited by A. -

The Hothouse and Dynamic Equilibrium in the Works of Harold Pinter

Ben Ferber The Hothouse and Dynamic Equilibrium in the Works of Harold Pinter I have no doubt that history will recognize Harold Pinter as one of the most influential dramatists of all time, a perennial inspiration for the way we look at modern theater. If other playwrights use characters and plots to put life under a microscope for audiences, Pinter hands them a kaleidoscope and says, “Have at it.” He crafts multifaceted plays that speak to the depth of his reality and teases and threatens his audience with dangerous truths. In No Man’s Land, Pinter has Hirst attack Spooner, who may or may not be his old friend: “This is outrageous! Who are you? What are you doing in my house?”1 Hirst then launches into a monologue beginning: “I might even show you my photograph album. You might even see a face in it which might remind you of your own, of what you once were.”2 Pinter never fully resolves Spooner’s identity, but the mens’ actions towards each other are perfectly clear: with exacting language and wit, Pinter has constructed a magnificent struggle between the two for power and identity. In 1958, early in his career, Pinter wrote The Hothouse, an incredibly funny play based on a traumatic personal experience as a lab rat at London’s Maudsley Hospital, proudly founded as a modern psychiatric institution, rather than an asylum. The story of The Hothouse, set in a mental hospital of some sort, is centered around the death of one patient, “6457,” and the unexplained pregnancy of another, “6459.” Details around both incidents are very murky, but varying amounts of culpability for both seem to fall on the institution’s leader, Roote, and his second-in- command, Gibbs. -

Politics, Oppression and Violence in Harold Pinter's Plays

Politics, Oppression and Violence in Harold Pinter’s Plays through the Lens of Arabic Plays from Egypt and Syria Hekmat Shammout A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS BY RESEARCH Department of Drama and Theatre Arts College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham May 2018 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract This thesis aims to examine how far the political plays of Harold Pinter reflect the Arabic political situation, particularly in Syria and Egypt, by comparing them to several plays that have been written in these two countries after 1967. During the research, the comparative study examined the similarities and differences on a theoretical basis, and how each playwright dramatised the topic of political violence and aggression against oppressed individuals. It also focussed on what dramatic techniques have been used in the plays. The thesis also tries to shed light on how Arab theatre practitioners managed to adapt Pinter’s plays to overcome the cultural-specific elements and the foreignness of the text to bring the play closer to the understanding of the targeted audience. -

The Dramatic World Harol I Pinter

THE DRAMATIC WORLD HAROL I PINTER RITUAL Katherine H. Bnrkman $8.00 THE DRAMATIC WORLD OF HAROLD PINTER By Katherine H. Burkman The drama of Harold Pinter evolves in an atmosphere of mystery in which the surfaces of life are realistically detailed but the pat terns that underlie them remain obscure. De spite the vivid naturalism of his dialogue, his characters often behave more like figures in a dream than like persons with whom one can easily identify. Pinter has on one occasion admitted that, if pressed, he would define his art as realistic but would not describe what he does as realism. Here he points to what his audience has often sensed is distinctive in his style: its mixture of the real and sur real, its exact portrayal of life on the surface, and its powerful evocation of that life that lies beneath the surface. Mrs. Burkman rejects the contention of some Pinter critics that the playwright seeks to mystify and puzzle his audience. To the contrary, she argues, he is exploring experi ence at levels that are mysterious, and is a poetic rather than a problem-solving play wright. The poetic images of the play, more over, Mrs. Burkman contends, are based in ritual; and just as the ancient Greeks at tempted to understand the mysteries of life by drawing upon the most primitive of reli gious rites, so Pinter employs ritual in his drama for his own tragicomic purposes. Mrs. Burkman explores two distinct kinds of ritual that Pinter develops in counter point. His plays abound in those daily habit ual activities that have become formalized as ritual and have tended to become empty of meaning, but these automatic activities are set in contrast with sacrificial rites that are loaded with meaning, and force the charac ters to a painful awareness of life from which their daily routines have served to protect them. -

Tacit Significance, Explicit Irrelevance: the Use of Language and Silence in the Caretaker and the Dumb Waiter

Revista de Lenguas ModeRnas, N° 16, 2012 / 31-48 / ISSN: 1659-1933 Tacit Significance, Explicit Irrelevance: The Use of Language and Silence in The Caretaker and The Dumb Waiter Juan Carlos saravia vargas Escuela de Lenguas Modernas Universidad de Costa Rica Abstract Readers who approach the Theater of the Absurd face complex interpreti- ve problems. The style of Harold Pinter, the laureate British playwright, adds an additional difficulty due to his particular use of language. His plays The Caretaker and The Dumb Waiter show how speech is overs- hadowed by silence, which provides a more direct access to the tortured psyche of characters. Key words: Theater of the Absurd, Harold Pinter, silence, dialog, plays, interpretation, The Caretaker, The Dumb Waiter Resumen El Teatro del absurdo presenta complejos problemas de interpretación a los lectores. El estilo del reconocido dramaturgo inglés Harold Pinter, representado en las obras El guardián y El Montaplatos, añade una difi- cultad adicional por su uso particular del lenguaje, donde la prominencia del discurso oral se ve opacada por el silencio. Es este último recurso dramático el que provee un acceso más directo a la torturada mente de los personajes. Palabras claves: teatro del absurdo, Harold Pinter, silencio, diálogo, obras, interpretación, El Guardián, El Montaplatos Recepción: 1-8-11 Aceptación: 5-12-11 32 Revista de Lenguas ModeRnas, n° 16, 2012 / 31-48 / ISSN: 1659-1933 heater, as a dramatic genre, has always posited an ontological problem for readers: since plays are intended to be staged, and not merely read, Tthe capacity of the reader to envision stage elements and their inter- action with characters might affect the interpretive experience of a dramatic work. -

Dialogical Interplay and the Drama of Harold Pinter Dialogical Interplay and the Drama of Harold Pinter

DIALOGICAL INTERPLAY AND THE DRAMA OF HAROLD PINTER DIALOGICAL INTERPLAY AND THE DRAMA OF HAROLD PINTER By JONATHAN STUART BOULTER, B.A.(Hons) A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University August, 1992 MASTER OF ARTS (1992) McMASTER UNIVERSITY (English) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: Dialogical Interplay and the Drama of Harold Pinter AUTHOR: Jonathan Stuart Boulter, Honours B.A. (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Dr. Anthony Brennan NUMBER OF PAGES: vii, 112 iii ABSTRACT The thesis is an effort to understand the way in which three of Pinter's early plays, The Birthday Party, A Slight Ache, and Tea Party are structured to work precise effects upon audiences. The underlying premise of this work is that Pinter compels his audience to assume an active role in the unfolding drama by manipulating the distance between audience and play. The activity of the audience can be understood to comprise two components. When confronted by the myriad questions posed by the Pinter play the audience begins to pose its own questions and to attempt to fix its own totalizing structures upon the play. I call this primary position of the audience its posture of hermeneutical inquiry. The second phase of the audience's participation in the play begins as the spectator notices that his or her own interpretive process is exactly analogous to that of the major characters in the drama. Any firm distinction in the ontological status of spectator and character is blurred. I have termed this blur "dialogical interplay": Pinter manipulates his audience to direct questions not only at the play, but to pose questions within the play itself. -

{Download PDF} the Dumb Waiter: Play

THE DUMB WAITER: PLAY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Harold Pinter | 40 pages | 31 Jan 2015 | Samuel French Ltd | 9780573042102 | English | London, United Kingdom The Dumb Waiter: Play PDF Book From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Get ready to write your essay on The Dumb Waiter. Ben bursts out loudly again about something he sees in the newspaper, but Gus quickly changes the subject to whether they could go to a football soccer game the next day. They begin to argue, and Gus passionately questions Ben about why their boss, a man named Wilson , wants them to do this job. Ben points his gun at the door, ready to shoot, as Gus enters the room. Our study guide has summaries, insightful analyses, and everything else you need to understand The Dumb Waiter. Ben has to explain to the people above via the dumbwaiter's "speaking tube" that there is no food. Two Person Three Person. Ben criticizes Gus for complaining about their job, which is not yet clear to the audience, saying that he gets plenty of time off. Remember me. To date, this content has been curated from Wikipedia articles and images under Creative Commons licensing, although as Project Webster continues to increase in scope and dimension, more licensed and public domain content is being added. Mostly male cast Includes adult characters. These horrors are dramatized through images of torture and oppression culminating in moments of silence that index the full extent of the destruction unleashed by the forces of power against dissidence. Another interpretation is that the play is a political drama showing how the individual is destroyed by a higher power. -

List-Of-Drama-Sets.Pdf

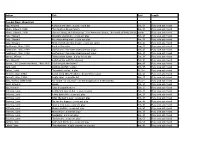

Author Title Cast Length One Act Plays: Mixed Cast Agg, Howard A shot in the dark : a play in one act 3m, 5f Play: one act mixed Albee, Edward, 1928- The death of Bessie Smith 4m, 2f Play: one act mixed Albee, Edward, 1928- The zoo story, and other plays : The American dream; The death of Betty Smith; and,varies The sandboxPlay: one act mixed Auty, Stewart Absolute discretion : a one act play 5m, 9f Play: one act mixed Auty, Stewart An unassuming man : a one act play 4m, 4f Play: one act mixed Auty, Stewart Here endeth the first lesson : a one act satire 4m, 4f Play: one act mixed Ayckbourn, Alan, 1939- A cut in the rates 1m, 2f Play: one act mixed Ayckbourn, Alan, 1939- Confusions : five interlinked one-act plays 3m; 2f Play: one act mixed Ayckbourn, Alan, 1939- Confusions : five interlinked one-act plays 3m, 2f Play: one act mixed Barnes, Wilson Thicker than water : a play in one act 5m, 3f Play: one act mixed Barr, Russell A dish of tea with Dr Johnson 7m; 3f Play: one act mixed Barrie, J. M. (James Matthew), 1860-1937 Shall we join the ladies? 8m, 8f Play: one act mixed Bate, Sam Decline and fall : a play 3m, 5f Play: one act mixed Bellon, Loleh Thursday's ladies : a play 4f; 2m. Play: one act mixed Bennett, Alan, 1934- A visit from Miss Prothero : (from Office suite) 1m, 1f Play: one act mixed Bennett, Alan, 1934- Single spies : a double bill 9m, 2f Play: one act mixed Blair, Wilfrid, 1889-1968 For home - or country? : an extravaganza [in three scenes] 5f; 1m.