Taking Covered Wagons East a New Innovation Theory for Energy and Other Established Technology Sectors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Overland-Cart-Catalog.Pdf

OVERLANDCARTS.COM MANUFACTURED BY GRANITE INDUSTRIES 2020 CATALOG DUMP THE WHEELBARROW DRIVE AN OVERLAND MANUFACTURED BY GRANITE INDUSTRIES PH: 877-447-2648 | GRANITEIND.COM | ARCHBOLD, OH TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents Need a reason to choose Overland? We’ll give you 10. 8 & 10 cu ft Wheelbarrows ........................ 4-5 10 cu ft Wheelbarrow with Platform .............6 1. Easy to operate – So easy to use, even a child can safely operate the cart. Plus it reduces back and muscle strain. Power Dump Wheelbarrows ........................7 4 Wheel Drive Wheelbarrows ................... 8-9 2. Made in the USA – Quality you can feel. Engineered, manufactured and assembled by Granite Industries in 9 cu ft Wagon ...............................................10 Archbold, OH. 9 cu ft Wagon with Power Dump ................11 3. All electric 24v power – Zero emissions, zero fumes, Residential Carts .................................... 12-13 environmentally friendly, and virtually no noise. Utility Wagon with Metal Hopper ...............14 4. Minimal Maintenance – No oil filters, air filters, or gas to add. Just remember to plug it in. Easy Wagons ...............................................15 5. Long Battery Life – Operate the cart 6-8 hours on a single Platform Cart ................................................16 charge. 3/4 cu yd Trash Cart .....................................17 6. Brute Strength – Load the cart with up to 750 pounds on a Trailer Dolly ..................................................17 level surface. Ride On -

Public Auction

PUBLIC AUCTION Mary Sellon Estate • Location & Auction Site: 9424 Leversee Road • Janesville, Iowa 50647 Sale on July 10th, 2021 • Starts at 9:00 AM Preview All Day on July 9th, 2021 or by appointment. SELLING WITH 2 AUCTION RINGS ALL DAY , SO BRING A FRIEND! LUNCH STAND ON GROUNDS! Mary was an avid collector and antique dealer her entire adult life. She always said she collected the There are collections of toys, banks, bookends, inkwells, doorstops, many items of furniture that were odd and unusual. We started with old horse equipment when nobody else wanted it and branched out used to display other items as well as actual old wood and glass display cases both large and small. into many other things, saddles, bits, spurs, stirrups, rosettes and just about anything that ever touched This will be one of the largest offerings of US Army horse equipment this year. Look the list over and a horse. Just about every collector of antiques will hopefully find something of interest at this sale. inspect the actual offering July 9th, and July 10th before the sale. Hope to see you there! SADDLES HORSE BITS STIRRUPS (S.P.) SPURS 1. U.S. Army Pack Saddle with both 39. Australian saddle 97. U.S. civil War- severe 117. US Calvary bits All Model 136. Professor Beery double 1 P.R. - Smaller iron 19th 1 P.R. - Side saddle S.P. 1 P.R. - Scott’s safety 1 P.R. - Unusual iron spurs 1 P.R. - Brass spurs canvas panniers good condition 40. U.S. 1904- Very good condition bit- No.3- No Lip Bar No 1909 - all stamped US size rein curb bit - iron century S.P. -

Chapter Rd Roadster Division Subchapter Rd-1 General Qualifications

CHAPTER RD ROADSTER DIVISION SUBCHAPTER RD-1 GENERAL QUALIFICATIONS RD101 Eligibility RD102 Type and Conformation RD103 Soundness and Welfare RD104 Gait Requirements SUBCHAPTER RD-2 SHOWING PROCEDURES RD105 General RD106 Appointments Classes RD107 Appointments RD108 Division of Classes SUBCHAPTER RD-3 CLASS SPECIFICATIONS RD109 General RD110 Roadster Horse to Bike RD111 Pairs RD112 Roadster Horse Under Saddle RD113 Roadster Horse to Wagon RD114 Roadster Ponies © USEF 2021 RD - 1 CHAPTER RD ROADSTER DIVISION SUBCHAPTER RD-1 GENERAL QUALIFICATIONS RD101 Eligibility 1. Roadster Horses: In order to compete all horses must be a Standardbred or Standardbred type. Roadster Ponies are not permitted to compete in Roadster Horse classes. a. All horses competing in Federation Licensed Competitions must be properly identified and must obtain a Roadster Horse Identification number from the American Road Horse and Pony Association (ARHPA). An ARHPA Roadster Horse ID number for each horse must be entered on all entry forms for licensed competitions. b. Only one unique ARHPA Roadster Horse ID Number will be issued per horse. This unique ID number must subsequently remain with the horse throughout its career. Anyone knowingly applying for a duplicate ID Number for an individual horse may be subject to disciplinary action. c. The Federation and/or ARHPA as applicable must be notified of any change of ownership and/or competition name of the horse. Owners are requested to notify the Federation and/or ARHPA as applicable of corrections to previously submitted information, e.g., names, addresses, breed registration, pedigree, or markings. d. The ARHPA Roadster Horse ID application is available from the ARHPA or the Federation office, or it can be downloaded from the ARHPA or Federation website or completed in the competition office. -

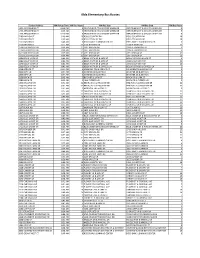

Elda Elementary Bus Routes

Elda Elementary Bus Routes Student Address AM Pickup Time AM Bus Route AM Bus Stop PM Bus Stop PM Bus Route 1399 ARROWHEAD CT 12:18 PM 6 ARROWHEAD CT & WAGON WHEEL DR ARROWHEAD CT & WAGON WHEEL DR 5 1449 ARROWHEAD CT 8:45 AM 5 ARROWHEAD CT & WAGON WHEEL DR ARROWHEAD CT & WAGON WHEEL DR 5 1449 ARROWHEAD CT 12:18 PM 6 ARROWHEAD CT & WAGON WHEEL DR ARROWHEAD CT & WAGON WHEEL DR 5 2189 BANYON CT 8:40 AM 18 ROSS COUNTRY DAY ROSS COUNTRY DAY 18 2204 BANYON CT 8:40 AM 18 ROSS COUNTRY DAY ROSS COUNTRY DAY 18 2207 BANYON CT 8:48 AM 6 ROSS EARLY LEARNING CENTER ROSS EARLY LEARNING CENTER 6 2216 BANYON CT 8:11 AM 23 3738 HERMAN RD 3738 HERMAN RD 23 2206 BEECHWOOD DR 8:39 AM 21 2397 BRENDA DR 2206 BEECHWOOD DR 3 2206 BEECHWOOD DR 8:39 AM 21 2397 BRENDA DR 2206 BEECHWOOD DR 3 2251 BEECHWOOD DR 8:39 AM 21 2397 BRENDA DR 2397 BRENDA DR 21 2251 BEECHWOOD DR 8:39 AM 21 2397 BRENDA DR 2397 BRENDA DR 21 2186 BELLA VISTA DR 8:44 AM 3 BELLA VISTA DR & LARK ST BELLA VISTA DR & LARK ST 3 2186 BELLA VISTA DR 8:44 AM 3 BELLA VISTA DR & LARK ST 2186 BELLA VISTA DR 16 2270 BELLA VISTA DR 8:44 AM 3 BELLA VISTA DR & LARK ST 2270 BELLA VISTA DR 16 2363 BELLA VISTA DR 8:43 AM 3 BELLA VISTA DR & CYPRESS LN BELLA VISTA DR & CYPRESS LN 3 2234 BERGER CT 12:13 PM 6 LEHMANN TRL & BERGER CT LEHMANN TRL & BERGER CT 5 2939 BETH LN 8:44 AM 6 JENNIFER DR & BETH LN JENNIFER DR & BETH LN 6 2939 BETH LN 8:44 AM 6 JENNIFER DR & BETH LN JENNIFER DR & BETH LN 6 2196 BIRCH DR 8:42 AM 3 BIRCH DR & LARK ST BIRCH DR & LARK ST 3 2283 BIRCH DR 8:43 AM 3 4016 CYPRESS LN BIRCH DR & CYPRESS -

History & STEM Fun with the Campbell County Rockpile Museum Wagons, Wagons, Wagons

History & STEM Fun with the Campbell County Rockpile Museum Wagons, Wagons, Wagons Covered wagons on Gillette Avenue - Campbell County Rockpile Museum Photo #2007.015.0036 To learn more about pioneer travels visit these links: https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=4&v=GdbnriTpg_M&feature=emb_logo https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5fJFUYKIVKA https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-XmWtLrfR-Y Most wagons on the Oregon Trail were NOT Conestoga wagons. These were slow, heavy freight wagons. Most Oregon Trail pioneers used ordinary farm wagons fitted with canvas covers. The expansion of the railroad into the American West in the mid to late 1800s led to the end of travel across the nation in wagons. Are a Prairie Schooner and a Conestoga the same wagon? No. The Conestoga wagon was a much heavier wagon and often pulled by teams of up to six horses. Such wagons required reasonably good roads and were simply not practical for moving westward across the plains. The entire wagon was 26 feet long and 11 feet wide. The front wheels were 3 ½ feet high, rear wheels 4 to 4 ½ feet high. The empty wagon weighed 3000 to 3500 lbs. The Prairie schooner was the classic covered wagon that carried settlers westward across the North American plains. It was a lighter wagon designed to travel great distances on rough prairie trails. It stood 10-foot-tall, was 4 ft wide, and was 10 to 12 feet long, When the tongue and yoke were attached it was 23 feet long. The rear wheels were 50 inches in diameter and the front wheels 44 inches in diameter. -

Wagon Trains

Name: edHelper Wagon Trains When we think of the development of the United States, we can't help but think of those who traveled across the country to settle the great lands of the West. What were their travels like? What images come to your mind when you think of this great migration? The wagon train is probably one of those images. What exactly was a wagon train? It was a group of covered wagons, usually around 100 of them. These carried people and their supplies to the West before there was a transcontinental railroad. From 1837 to 1841, many people were in frustrating economic situations. Farmers, businessmen, and fur traders were looking for new opportunities. They hoped for a better climate, good crops, and better conditions. They decided to travel to the West. Missionaries wanted to convert American Indians to Christianity. They decided to head to the West. Why would these groups head out together? First of all, the amount of traveling was incredible. Much of the country they were traveling through was not settled and was difficult to travel. The trip could be confusing because of other trails made by Indians and buffalos. To get there safely, they went together. Second of all, there was a real danger that a wagon would be attacked by Native Americans. In order to have protection, it made sense to travel together. Wagon trains were very organized. People signed up to join one. There was a contract that stated the goals of the group's trip, terms to join, rules, and the details for electing officers. -

Sand Canyon & Rock Creek Trails

Sand Canyon & Rock Creek Trails Canyons of the Ancients National Monument © Kim Gerhardt CANYONS OF THE ANCIENTS NATIONAL MONUMENT Ernest Vallo, Sr. Canyons of the CANYONS Eagle Clan, Pueblo of Acoma: Ancients National OF THE Monument ANCIENTS MAPS & INFORMATION When we come to and the Anasazi a place like Sand Heritage Center Anasazi Heritage Canyon, we pray Center to the ancestral 27501 Highway 184, Hovenweep people. As Indian Dolores, CO 81323 National Monument Canyons people we believe Tel: (970) 882-5600 of the 491 the spirits are Hours: Ancients still here. National Monument 9–5 Summer Mar.- Oct. We ask them Road G for our strength 10–4 Winter Nov.- Feb. and continued https://www.blm.gov/ 160 Mesa Verde survival, and programs/national- 491 National Park thank them conservation-lands/ colorado/canyons-of-the- for sharing their home place. In the Acoma ancients language I say, “Good morning. I’ve brought A public land administered my friends. If we approached in the wrong way, by the Bureau of Land please excuse our ignorance.” Management. 2 Please Stay on Designated Trails Welcome to the Sand Canyon & Rock Creek Trails 3 anyons of the Ancients National Monument was created to protect cultural and Cnatural resources on a landscape scale. It is part of the Bureau of Land Management’s National Landscape Conservation System and includes almost 171,000 acres of public land. The Sand Canyon and Rock Creek Trails are open for hiking, mountain biking, or horseback riding on designated routes only. Most of the Monument is backcountry. Visitors to Canyons of the Ancients are encouraged to start at the Anasazi Heritage Center near Dolores, Mountain Biking Tips David Sanders Colorado, where they can get current information from local rider Dani Gregory: Park Ranger, Canyons of the Ancients: about the Monument and experience the museum’s • Hikers and bikers are supposed to stop for • All it takes is for exhibits, films, and hands-on discovery area. -

Amongamerican Inventions the Conestoga Wagon Must Forever

THE CONESTOGA WAGON OF PENNSYLVANIA Michael J. Herrick: I60NQ American inventions thetne ConestOAaConestoga wa^onwagon must koreverforever be remembered with respect, for it was this wagon that •*Among orpa servicedG&ririn&A ara rapidlyroT^irHir settlingco+tiinrr western frontier.\u25a0Prnn+iAr* TheT'Vua area covering/wir#»i-itncr the state of Pennsylvania and extending to the whole of the Northwest Territory was promising land for free men and farmers. Men over- flowed the old colonies and looked to the West — the Alleghenies. They came here and carved out farms from the forest and prospered. The promise of prosperity brought with it the need for supplies, equipment, markets, transportation. To satisfy these needs, Pennsyl- vania originated the pack-horse trade and the Conestoga horse and wagon. Inthe years to follow this simple beginning, the Conestoga was to become one of the greatest freight vehicles America has ever known. 1 The Dutch farmers, who had moved into the fertile lands of Penn- sylvania, cleared away the forests to settle down on large plots of land and to force their livelihood from the earth. In a few years with frugality, fertile lands, industrious ways, and hard work, these German farmers found relative prosperity. They were soon producing and manufacturing enough to be able to sell at a good market, but where ? Over in Baltimore, Philadelphia and New York were good markets for coal, grain and meat. Yet the farmers had a logistics problem to solve first: how could they transport their goods that far, fast enough ? Certainly every farm had some type of cart or wagon to haul farm products. -

4-H Driving Manual

4-H Driving Manual A Pacific Northwest Extension Publication Oregon State University • Washington State University • University of Idaho PNW 229 Introduction Use this 4-H Driving Manual as you learn Driving is a valuable training option for light how to train your animal, fit the harness properly, horses, draft horses, ponies, donkeys, mules, and drive your animal safely. The manual or miniature horses. For example, when a 4-H outlines one of several accepted ways of training. member grows too large to ride a pony, he or See “For More Information” (page 27) for she can learn to drive it. A full-size young horse other publications that can help you continue to can be driven before it’s physically ready for expand your knowledge. riding, which shortens training time and gives 4-H members can use the 4-H Driving Manual it experience. A mature riding horse’s value to train any equine to drive. For simplicity’s increases if it can also pull a cart. sake, the manual uses the word “horse” to stand For driving, you need a vehicle and harness. for all equines. Vehicles and harnesses are available in several Words that appear in the text in SMALL CAPS are price ranges through tack stores or catalogs. The found in the Glossary. driver, horse, vehicle, and harness together are referred to as the TURNOUT. The 4-H Driving Manual was developed and written by the Pacific Northwest (PNW) 4-H Driving Publication Committee. The team was led by Erika Thiel, 4-H program coordinator, University of Idaho. -

A Carriage Ride Through History

Photo: Captain Tucker/Wikimedia Commons Captain Tucker/Wikimedia Photo: A Carriage Ride Through History By Margaret Evans From pony cart to coronation coach, few vehicles have had such a colourful history as the horse-drawn carriage. Ever since the wheel was first invented the disc and at the ends of the axle had to be have a cart. It you hitched a horse to the front around 3,500 BC in Mesopotamia as a perfectly smooth and round in order for the end, you’d have an animal to pull it, which wooden disc with a hole in the middle for wheel to fit and turn. Otherwise, too much would save doing it yourself. With the some form of axle, creative Sumarian minds friction would cause breakage. domestication of the horse almost 6,000 years were buzzing. They were, after all, already The wheel for transportation actually ago, a marriage between the cart and the planting crops, herding animals, and had a followed the invention of the potter’s wheel. horse was inevitable, eventually pretty impressive social order. But getting But those Bronze Age inventors wasted little transforming a civilization. On the Sumerian the wheel contraption right took a bit of time connecting the dots and figuring out Battle Standard of Ur is the depiction of an creative genius. The holes in the centre of that if you put a box on top of the axle, you’d onager-drawn cart from 2,500 BC. 56 Equine Consumers’ Guide 2016 CANADA’S HORSE INDUSTRY AT YOUR FINGERTIPS Photo: David Crochet/Wikimedia Commons Crochet/Wikimedia David Photo: Photo: Steve F-E-Cameron/Wikimedia Commons F-E-Cameron/Wikimedia Steve Photo: Photo: David Crochet/Wikimedia Commons Crochet/Wikimedia David Photo: The earliest form of a “carriage” (from Old became the defining form of transport. -

The Cowboy's Gear

The Cowboy's Gear Grade Level: 4 - 5 Subject: Social Studies, Information Literacy, Language Arts Duration: 1 hour Description: The purpose of this lesson is to give students an awareness of cowboy life and the clothing and equipment he used. PASS—Oklahoma Priority Academic Student Skills Social Studies 1.1 Demonstrate the ability to utilize research materials, such as encyclopedias, almanacs, atlases, newspapers, photographs, visual images, and computer-based technologies. (Grade 4) Social Studies 5.1 Identify major historical individuals, entrepreneurs, and groups, and describe their major contributions. (Grade 4) Social Studies 1.1 Locate, gather, analyze, and apply information from primary and secondary sources using examples of different perspectives and points of view. (Grade 5) Social Studies 6.3 Relate some of the major influences on westward expansion to the distribution and movement of people, goods, and services. (Grade 5) Language Arts-Writing/Grammar/Usage and Mechanics 3.4.a Create interesting sentences using words that describe, explain, or provide additional details and connections, such as adjectives, adverbs, appositives, participial phrases, prepositional phrases, and conjunctions. (Grade 4 - 5) Information Literacy 1.3 Identify and use a range of information sources. Goals: Students will gain knowledge of a cowboy’s way of life by learning about clothing and equipment. Objectives: • Students will learn how a cowboy’s work and environment affected his choice of clothing and equipment. • Students will write an original story describing cowboy life. Assessment: Students will complete “A Cowboy’s Gear” worksheet and crossword puzzle. Students will write a brief story, including cowboy gear, using the “Four Part Story” worksheet. -

Transportation: Past, Present and Future “From the Curators”

Transportation: Past, Present and Future “From the Curators” Transportationthehenryford.org in America/education Table of Contents PART 1 PART 2 03 Chapter 1 85 Chapter 1 What Is “American” about American Transportation? 20th-Century Migration and Immigration 06 Chapter 2 92 Chapter 2 Government‘s Role in the Development of Immigration Stories American Transportation 99 Chapter 3 10 Chapter 3 The Great Migration Personal, Public and Commercial Transportation 107 Bibliography 17 Chapter 4 Modes of Transportation 17 Horse-Drawn Vehicles PART 3 30 Railroad 36 Aviation 101 Chapter 1 40 Automobiles Pleasure Travel 40 From the User’s Point of View 124 Bibliography 50 The American Automobile Industry, 1805-2010 60 Auto Issues Today Globalization, Powering Cars of the Future, Vehicles and the Environment, and Modern Manufacturing © 2011 The Henry Ford. This content is offered for personal and educa- 74 Chapter 5 tional use through an “Attribution Non-Commercial Share Alike” Creative Transportation Networks Commons. If you have questions or feedback regarding these materials, please contact [email protected]. 81 Bibliography 2 Transportation: Past, Present and Future | “From the Curators” thehenryford.org/education PART 1 Chapter 1 What Is “American” About American Transportation? A society’s transportation system reflects the society’s values, Large cities like Cincinnati and smaller ones like Flint, attitudes, aspirations, resources and physical environment. Michigan, and Mifflinburg, Pennsylvania, turned them out Some of the best examples of uniquely American transporta- by the thousands, often utilizing special-purpose woodwork- tion stories involve: ing machines from the burgeoning American machinery industry. By 1900, buggy makers were turning out over • The American attitude toward individual freedom 500,000 each year, and Sears, Roebuck was selling them for • The American “culture of haste” under $25.