Hendra in the News: Public Policy Meets Public Morality at a Time of Zoonotic Uncertainty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hendra Virus – a One Health Success Story

Under the Microscope Hendra virus – a One Health success story Hume Field Queensland Centre for Emerging Brad McCall Infectious Diseases 39 Kessels Road, Coopers Plains Brisbane Southside Public Health Unit, Brisbane, Qld 4108, Australia PO Box 333, Archerfield Tel +61 7 3276 6054 Qld 4108, Australia Fax +61 7 3216 6591 Tel +61 7 3000 9148 Email [email protected] Fax +61 7 3000 9130 Zoonoses account for 60% of emerging diseases spp.) as the natural reservoir of the virus in 1996 provided threatening humans. Wildlife are the origin of an the complex wildlife-livestock-human continuum illustrated increasing proportion of zoonoses over recent decades to by Daszak et al., 20005, and thus invited a cross-disciplinary a point where they now account for 75% of all zoonoses1. approach. A succession of equine incidents (some single cases, Concurrently and/or consequentially, there has been some involving horse to horse transmission) has occurred since an increasing recognition of the inter-connectedness 1994, several involving horse to human transmissions6 (Figure 1). of wildlife, livestock and human health, and increasing In 2012, the response to diagnosis of an equine case invokes momentum of an ecosystem-level approach (most a coordinated multi-agency threat abatement team approach. commonly termed One Health) to complex emerging Animal health authorities report a positive diagnosis to public disease scenarios2. This paper describes the evolution health, wildlife and workplace health and safety authorities. and application of such an approach to periodic Hendra There is cross-agency coordination not only at the policy and virus incidents in horses and humans in Australia. -

Hendra Virus and Australian Wildlife Fact Sheet

Hendra virus and Australian wildlife Fact sheet Introductory statement Hendra virus (HeV) causes a potentially fatal disease of horses and humans. HeV emerged in 1994 and cases to date have been limited to Queensland (Qld) and New South Wales (NSW), where annual incidents are now reported. Flying-foxes are the natural reservoir of the virus. Horses are infected directly from flying-foxes or via their urine, body fluids or excretions. All human cases have resulted from direct contact with infected horses. Evidence of infection has been seen in two dogs that were in contact with infected horses. HeV has attracted international interest as one of a group of diseases of humans and domestic animals that has emerged from bats since the 1990s. HeV does not cause evident clinical disease in flying-foxes and direct transmission to humans from bats has not been demonstrated. Ongoing work is required to understand the ecology and factors driving emergence of this disease. Aetiology HeV is a RNA virus belonging to the family Paramyxoviridae, genus Henipavirus. Natural hosts There are four species of flying-fox on mainland Australia: Pteropus alecto black flying-fox Pteropus conspicillatus spectacled flying-fox Pteropus scapulatus little red flying-fox Pteropus poliocephalus grey-headed flying-fox While serologic evidence of HeV infection has been found in all four species (Field 2005), more recent research suggests that two species, the black flying-fox and spectacled flying-fox, are the primary reservoir hosts (Field et al. 2011; Smith et al. 2014; Edson et al. 2015; Goldspink et al. 2015). The impact of HeV infection on flying-fox populations is presumed to be minimal. -

High Stakes of the Hendra Virus | the Australian Page 1 of 5

High stakes of the Hendra virus | The Australian Page 1 of 5 http://www.theaustralian.com.au/news/features/high-stakes/story-e6frg8h6-1226597475505Go MAR APR MAY Close 46 captures 23 Help 16 Mar13 - 23 Apr13 2012 2013 2014 THE AUSTRALIAN High stakes of the Hendra virus JAMIE WALKER THE AUSTRALIAN MARCH 16, 2013 12:00AM Beohm: "I look fine on the outside but I am broken on the inside." Picture: Julian Kingma Source: Supplied THE gum trees were blooming when Natalie Beohm fell ill, their flowers creamy and feather-like in the breeze that whispered off Queensland's Moreton Bay. It was July 2008 and the young woman had the job she had always wanted at the Redlands Veterinary Clinic, looking after horses and working with people who were more like family than colleagues. Looking back, it seems like another life. Her life before Hendra virus. "I'm still tired all the time," Beohm is saying, nearly five long years later. She has ventured to Melbourne to find herself, such as she can, after contracting a disease that has baffled and horrified scientists and doctors in equal measure. "I still get pain all down my right side. I get night tremors. I can't hear out of my right ear," she explains, the weariness heavy in her voice. "I could keep going on about what this thing has done to me, but what's the point? I just have to live with it." Beohm, 25, is one of only three known survivors of Hendra virus. Her friend and mentor, Ben Cunneen, a 33-year-old equine vet who was also struck down, died the day after she was released from hospital. -

How Can We Manage Hendra Virus in Australia?

MARCH 2019 How can we manage Hendra virus in Australia? Authors: Chris Degeling, Gwendolyn Gilbert, Edward Annand, Melanie Taylor, Michael Walsh, Michael Ward, Andrew Wilson, and Jane Johnson Associate Editors: Elitsa Panayotova and Rachel Watson Abstract Bats are very important for the environment, but they can virus management, since the underlying cause of Hendra transmit several dangerous viruses, including not only the virus emergence seems to be habitat loss. To find out what dreaded Ebola but also Hendra virus. Hendra virus affects Australian citizens think about it, we asked three community both horses and people and can be lethal. The measures juries whether they think such a strategy is appropriate. Even Australia (where the virus is present) has so far taken include though they all agree the government should implement horse vaccination and safer practice promotion among ecological approaches to manage Hendra, the juries prioritize horse owners. Additional ecological approaches such as increasing resources for the current measures: horse bat habitat protection and creation could enhance Hendra vaccination and safer practices among horse owners. Introduction All of these measures are still not enough to manage HeV. There are several myths surrounding bats, such as that they will They don’t take into account the underlying cause for the attack you or even want to drink your blood! Many people also emergence of HeV: bats’ habitat loss. People clear forests see them as pests, but in fact they are very helpful creatures. for agriculture, which forces bats to move closer to our food The bats known as flying foxes in Australia eat nectar and pollen sources. -

October 2009

Official Newsletter ofWildcare Australia. WILDSpring 2009 Issue 54 NEWS Swimming with humpbacks. Flying Foxes and Hendra Virus. This newsletter is proudly sponsored by Brett Raguse, MP Federal Member for Forde. COVER PHOTO: GABI 2 PHOTO // LAURA REEDER WILDNEWS Karen Scott President’sHI EVERYONE, FIRSTLY, THANK YOU TO EVERYONE WHO Your Report. contribution is very much appreciated. BRAVED THE TRAffIC IN LATE JUNE TO ATTEND THE WILD- This coming year is going to be a good one and we are CARE ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING AT BEERWAH. It was already off to a great start. We have a new fundraising great to have the AGM north of Brisbane for a change, to committee just getting started with some great ideas and enable people who previously have been unable to attend enthusiasm. We are also in the process of setting up a because of distance and animal commitments, the oppor- Community Education Team who will be responsible for tunity to participate and catch up with friends. We will delivering talks to schools and community groups. If definitely make sure that we rotate the AGM in future. you are still trying to find your ‘niche’ in Wildcare, maybe Secondly, thank you to Tracy Paroz, who is continuing in one of these sub-committees is for you. the role of secretary, and welcome to committee mem- Let’s hope that the coming spring season is not too bers Tonya Howard, Laura Reeder and Amy Whitman, hectic although things seem to have started early this our new extended Management Committee. They have year with baby birds already coming into care. -

Hendra Virus Infection a Threat to Horses and Humans Geoffrey Playford

Hendra virus infection A threat to horses and humans Geoffrey Playford Infection Management Services | Princess Alexandra Hospital Department of Microbiology | Pathology Queensland [email protected] Overview • Virology, pathogenesis • Epidemiology • Clinical disease in humans • Histopathological, neuro -histopathological insights • Prevention of human infection, public health responses • Recent developments in therapeutics Recently described paramyxoviruses associated with bats • Hendra virus (Australia, 1994) • Menangle virus (Australia, 1997) • Nipah virus (Malaysia, 1998) • Tioman virus (Malaysia, 1999) Pteropus poliocephalus World distribution of flying foxes (genus Pteropus ) From: Field et al., CTMI 2007;315:133-59 Background Hendra virus • Family Paramyxoviridae – Subfamily Paramyxovirinae • Genus Henipavirus • First recognised 1994 from outbreak at Hendra horse stables in Brisbane • Initially designated: – Acute equine respiratory syndrome – Equine morbillivirus From: Eaton et al., Nature Rev Microbiol 2006;4:23-35 Hendra virus structure and genome • Large genome: 18,234 nucleotides (~15% longer than most other paramyxoviruses) • Typical paramyxovirus genome structure From: Eaton et al ., Nature Rev Microbiol 2006;4:23-35 F Attachment, fusion, cell entry G Ephrin-B2 • Explains: – Broad host range Host cell – Systemic nature of infection • G glycoprotein – Binds to Ephrin -B2 – Highly conserved and ubiquitously-distributed surface glycoprotein – Present in small arterial endothelial cells & neurones – Ligand for Eph class of receptor tyrosine kinases • F glycoprotein: – Precursor (F 0) cleaved into biologically active F 1 & F 2 by lysosomal cysteine protease Cathepsin L after endocytosis – Conformational change into trimer-of-hairpins structure Bonaparte MI, et al . (2005). PNAS 102: 10652-57. Bishop KA, et al . (2007) J Virol 81: 5893-5901. Negrete OA, et al . (2005) Nature 436: 401-405. -

Flying-Foxes in the Coolum Beach Area Management Options Report April 2016

Flying-foxes in the Coolum Beach Area Management Options Report April 2016 Sunshine Coast Council ecology / vegetation / wildlife / aquatic ecology / GIS Executive summary There are three species of colonial flying-foxes known to occur within the Sunshine Coast Council area: the grey-headed flying-fox (Pteropus poliocephalus), black flying-fox (P. alecto), and little red flying-fox (P. scapulatus). There are currently three known roost sites in Coolum, which include Palmer Coolum (then Coolum Hyatt), Cassia Wildlife Corridor and Elizabeth Street (Tradewinds Avenue). All three flying-fox species have been known to roost at the latter two sites, which has led to community concern and complaints for a number of years. Council is committed to addressing community concerns regarding flying-foxes roosting in urban areas, as well as conserving these important native species and complying with environmental legislation. To assist with this and provide a flying-fox management framework, Council has developed an adaptive Regional Flying-fox Management Plan. The Cassia Wildlife Corridor roost site is a narrow strip of Council-managed vegetation with high potential for community/flying-fox conflict, for which all management options are to be considered. Due to the roost’s extremely close proximity to a large number of residents, and the inability to manage it in-situ, Council endorsed a non-lethal dispersal program in 2013. Flying foxes have not returned to this site, however an additional roost established nearby at Elizabeth Street Drain in 2014. The Elizabeth Street Drain roost established in September 2014, two months after dispersal activities were completed at the nearby Cassia Wildlife Corridor. -

Horses, Humans and Hendra Virus

Under the Microscope Horses, humans and Hendra virus may reflect the most impacted organ system, which in turn, may reflect route of infection, viral dose, or virus strain (although the recent AAHL studies did not attach great significance to the latter). Spillover of Hendra virus from bats to horses is a rare event, given a horse population in Australia estimated in excess of Hume Field 200,000 and the substantial geographic overlap of the occurrence of flying foxes and horses. The lack of an effective treatment Biosecurity Queensland Queensland Primary Industries modality either for horses or humans, plus the absence of a and Fisheries protective vaccine for either, limits risk management to exposure Email [email protected] minimisation, early detection and effective case biosecurity. Animal health authorities in Australia foster increased awareness, alertness and preparedness in the horse-owning and veterinary Hendra virus again demonstrated its zoonotic capacity communities and encourage husbandry practices to minimise with the infection of two veterinary clinic staff (one the risk of exposure of horses to flying foxes. Infection in the fatally) in an outbreak in a Brisbane equine referral latter causes no evident disease and, based on serologic studies, veterinary practice in 2008. Bats are recognised as the is widespread, both taxonomically and geographically. The natural host of the virus. apparent recent emergence of Hendra virus (and a number of other novel agents) from flying foxes has been attributed to Hendra virus, a large, pleomorphic, enveloped, ribonucleic cumulative negative ecological impacts that have precipitated acid (RNA) virus, was initially considered a morbillivirus, but changes in population dynamics and infection dynamics. -

I Tried to Send This Last Night and It Was Sent Back. It Seems I May Have Made One Small Error with the Address

To: Committee, Queensland Government Administration (SEN) Subject: FW: Submission - Inquiry - Qld Government Date: Wednesday, 19 November 2014 11:18:14 PM Attachments: dot points - HeV issues.docx Case History (Peachester 2007).docx very last submission PRIVATE AND CONFIDENTIAL.docx I tried to send this last night and it was sent back. It seems I may have made one small error with the address. My apologies. I spoke with one of your representatives today who suggested I try again. Susan Richardson From: Sue Richardson Sent: Tuesday, 18 November 2014 10:05 PM To: '[email protected].' Subject: Submission - Inquiry - Qld Government Dear Sir/Madam I had no idea any such thing was happening, regarding complaints about the Qld Government. I have only just arrived home and opened an email stating that submissions must be in by the close of business today. Obviously I have missed this by hours. I feel crushed. Please bear with me as I will explain. Please read further. I am begging you to allow me a later date and here is why. My computer recently crashed and I lost all data – all of that which I would have submitted is in hard copy in boxes. I have some documents held in my computer which I have asked an interested party to return to me via USB. I have fought so long and hard and got nowhere – to the point where I have now lost my family, nearly lost my home, and in short – a grave injustice has been done to the people of Queensland, the wildlife of Queensland and I firmly believe that people have died as a result. -

Nipah Virus: Past Outbreaks and Future Containment

viruses Review Nipah Virus: Past Outbreaks and Future Containment Vinod Soman Pillai y, Gayathri Krishna y and Mohanan Valiya Veettil * Virology Laboratory, Department of Biotechnology, Cochin University of Science and Technology, Cochin 682022, Kerala, India; [email protected] (V.S.P.); [email protected] (G.K.) * Correspondence: [email protected] These authors contributed equally to this work. y Received: 13 March 2020; Accepted: 8 April 2020; Published: 20 April 2020 Abstract: Viral outbreaks of varying frequencies and severities have caused panic and havoc across the globe throughout history. Influenza, small pox, measles, and yellow fever reverberated for centuries, causing huge burden for economies. The twenty-first century witnessed the most pathogenic and contagious virus outbreaks of zoonotic origin including severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV), Ebola virus, Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) and Nipah virus. Nipah is considered one of the world’s deadliest viruses with the heaviest mortality rates in some instances. It is known to cause encephalitis, with cases of acute respiratory distress turning fatal. Various factors contribute to the onset and spread of the virus. All through the infected zone, various strategies to tackle and enhance the surveillance and awareness with greater emphasis on personal hygiene has been formulated. This review discusses the recent outbreaks of Nipah virus in Malaysia, Bangladesh and India, the routes of transmission, prevention and control measures employed along with possible reasons behind the outbreaks, and the precautionary measures to be ensured by private–public undertakings to contain and ensure a lower incidence in the future. Keywords: emerging virus; Nipah; outbreak; transmission; prevention; control 1. -

Compendium of Findings from the National Hendra Virus Research Program COMPENDIUM of FINDINGS from the 2 NATIONAL HENDRA VIRUS RESEARCH PROGRAM

Department of Agriculture and Water Resources Department of Environment Department of Industry, Innovation and Science National Health and Medical Research Council Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation Compendium of findings from the National Hendra Virus Research Program COMPENDIUM OF FINDINGS FROM THE 2 NATIONAL HENDRA VIRUS RESEARCH PROGRAM © 2016 Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation. All rights reserved. ISBN 978-1-74254-847-0 ISSN 1440-6845 Compendium of findings from the National Hendra Virus Research Program Publication No. 16/001 The information contained in this publication is intended for general use to assist public knowledge and discussion and to help improve the development of sustainable regions. You must not rely on any information contained in this publication without taking specialist advice relevant to your particular circumstances. While reasonable care has been taken in preparing this publication to ensure that information is true and correct, the Commonwealth of Australia gives no assurance as to the accuracy of any information in this publication. The Commonwealth of Australia, the Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation (RIRDC), the authors or contributors expressly disclaim, to the maximum extent permitted by law, all responsibility and liability to any person, arising directly or indirectly from any act or omission, or for any consequences of any such act or omission, made in reliance on the contents of this publication, whether or not caused by any negligence on the part of the Commonwealth of Australia, RIRDC, the authors or contributors. The Commonwealth of Australia does not necessarily endorse the views in this publication. This publication is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all other rights are reserved. -

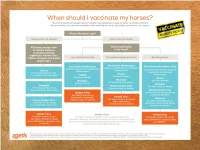

Vaccination Protocols Are Followed and All Horses Are Vaccinated Against the Hendra Virus

1 Hendra virus Equivac HeV 2 HENDRA FROM 1994–2014 Macksville, NSW Lowood, Qld Macksville, NSW Gold Coast, Qld Kempsey, NSW Kempsey, NSW In 2014 : Bundaberg, Qld Beenleigh, Qld Murwillumbah, NSW Calliope, QLD 3 BAT DISTRIBUTION – 2000 TO 2013 ADAPTED FROM RICHARDS, HALL AND PARISH (2012)6 . Fruit bats (flying foxes) are the natural hosts of Hendra virus . Fruit bats range over a large portion of the Australian mainland. Infected fruit bats do not exhibit signs of illness from the Hendra virus3 4 SIGNS OF HENDRA VIRUS IN HORSES (FOLLOWING INCUBATION PERIOD OF 5-16 DAYS) Common symptoms may include any one or combination of the following • Acute onset of illness • Increased body temperature • Increased heart rate • Discomfort/weight shifting between legs • Rapid deterioration with respiratory and neurological signs Other clinical observations Respiratory signs Neurological signs • Congestion & fluid on the lungs • Wobbly gait • Difficulty breathing • Altered consciousness • Nasal discharge- initially clear then frothy • Head tilting white/blood stained • Muscle twitching • Weakness, loss of coordination, collapse • Urinary incontinence Other clinical observations may be noted If you have observed any of these symptoms or you are concerned about your horse, consult your veterinarian immediately 5 SIGNS OF HENDRA VIRUS IN HUMANS Clinical signs and symptoms Influenza-like symptoms Neurological signs Fever Encephalitis with headache Cough Fever Sore throat Drowsiness Other clinical observations may be noted . Horse to human transmission can