Applying the De Minimis Exception to Digital Sound Sampling in the Wake of Vmg Salsoul, Llc V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Patriot Press March-April 2017

Patriot Press Page Guide News..........................................1 @LibertyPublicat Features......................................2 Entertainment..........................3-5 Center Spread............................6-7 Sports.....................................8-10 Viewpoint...................................11 Back Page..................................12 www.pinterest.com/tyearbook March/April 2017 Volume 23: Issue 5 6300 Independence Avenue, Bealeton, Virginia 22712 Safe Dating Experts Stress “Love Should Be Respectful.” by Savannah Johnson This year Liberty High School ~Staff Reporter ly learn from others and share positive decided to try something new by offer- pieces of those experiences with others,” ing a safe dating workshop. From Jan- Abuse said social worker Rochelle Ferguson. uary 25 until April 5 in the Eagle Room, Acts of violence, threats of violence, Students in this workshop do var- there are sessions held to teach students victim-blaming, intimidation ious activities to help us spot abusive be- about positive and non-positive relation- havior. They read scenarios and with ev- ships. Professional social workers Ro- erything that happens, and they decide if chelle Ferguson and Lauren Dracoules they would leave or stay in that situation. are the ones who are teaching this class. Tension Building Reconciliation The class gets handouts with examples Safe Dates’ primary purpose is to Tensions increase, breakdown of Excuses, apologies, denial of abuse, they can look back on. Also papers that equip individuals at the school who are en- communication survivor is fearful victim-blaming they fill out remind them what they want tering the dating arena and/or advise those and need out of a relationship. Students do who are currently in a relationship. The not just learn how they should be treated, tools students gain from this class will help they also learn how to treat their partners. -

Thou Shalt Not Steal: Grand Upright Music Ltd. V. Warner Bros. Records, Inc. and the Future of Digital Sound Sampling in Popular Music, 45 Hastings L.J

Hastings Law Journal Volume 45 | Issue 2 Article 4 1-1994 Thou hS alt Not Steal: Grand Upright Music Ltd. v. Warner Bros. Records, Inc. and the Future of Digital Sound Sampling in Popular Music Carl A. Falstrom Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Carl A. Falstrom, Thou Shalt Not Steal: Grand Upright Music Ltd. v. Warner Bros. Records, Inc. and the Future of Digital Sound Sampling in Popular Music, 45 Hastings L.J. 359 (1994). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol45/iss2/4 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thou Shalt Not Steal: Grand Upright Music Ltd. v. Warner Bros. Records, Inc. and the Future of Digital Sound Sampling in Popular Music by CARL A. FALSTROM* Introduction Digital sound sampling,1 the borrowing2 of parts of sound record- ings and the subsequent incorporations of those parts into a new re- cording,3 continues to be a source of controversy in the law.4 Part of * J.D. Candidate, 1994; B.A. University of Chicago, 1990. The people whom I wish to thank may be divided into four groups: (1) My family, for reasons that go unstated; (2) My friends and cohorts at WHPK-FM, Chicago, from 1986 to 1990, with whom I had more fun and learned more things about music and life than a person has a right to; (3) Those who edited and shaped this Note, without whom it would have looked a whole lot worse in print; and (4) Especially special persons-Robert Adam Smith, who, among other things, introduced me to rap music and inspired and nurtured my appreciation of it; and Leah Goldberg, who not only put up with a whole ton of stuff for my three years of law school, but who also managed to radiate love, understanding, and support during that trying time. -

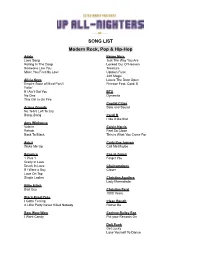

Band Song-List

SONG LIST Modern Rock, Pop & Hip-Hop Adele Bruno Mars Love Song Just The Way You Are Rolling In The Deep Locked Out Of Heaven Someone Like You Treasure Make You Feel My Love Uptown Funk 24K Magic Alicia Keys Leave The Door Open Empire State of Mind Part II Finesse Feat. Cardi B Fallin' If I Ain't Got You BTS No One Dynamite This Girl Is On Fire Capital Cities Ariana Grande Safe and Sound No Tears Left To Cry Bang, Bang Cardi B I like it like that Amy Winhouse Valerie Calvin Harris Rehab Feel So Close Back To Black This is What You Came For Avicii Carly Rae Jepsen Wake Me Up Call Me Maybe Beyonce Cee-lo Green 1 Plus 1 Forget You Crazy In Love Drunk In Love Chainsmokers If I Were a Boy Closer Love On Top Single Ladies Christina Aguilera Lady Marmalade Billie Eilish Bad Guy Christina Perri 1000 Years Black-Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling Clean Bandit A Little Party Never Killed Nobody Rather Be Bow Wow Wow Corinne Bailey Rae I Want Candy Put your Records On Daft Punk Get Lucky Lose Yourself To Dance Justin Timberlake Darius Rucker Suit & Tie Wagon Wheel Can’t Stop The Feeling Cry Me A River David Guetta Love You Like I Love You Titanium Feat. Sia Sexy Back Drake Jay-Z and Alicia Keys Hotline Bling Empire State of Mind One Dance In My Feelings Jess Glynne Hold One We’re Going Home Hold My Hand Too Good Controlla Jessie J Bang, Bang DNCE Domino Cake By The Ocean Kygo Disclosure Higher Love Latch Katy Perry Dua Lipa Chained To the Rhythm Don’t Start Now California Gurls Levitating Firework Teenage Dream Duffy Mercy Lady Gaga Bad Romance Ed Sheeran Just Dance Shape Of You Poker Face Thinking Out loud Perfect Duet Feat. -

Bridgeport Music, Inc. V. Dimension Films, 383 F.3D 390 (6Th Cir

RECOMMENDED FOR FULL-TEXT PUBLICATION Pursuant to Sixth Circuit Rule 206 File Name: 05a0243a.06 UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT _________________ No. 02-6521 X BRIDGEPORT MUSIC, INC.; WESTBOUND RECORDS, - INC., - - Nos. 02-6521; 03-5738 Plaintiffs-Appellants, - SOUTHFIELD MUSIC, INC.; NINE RECORDS, INC., > , Plaintiffs, - - v. - - DIMENSION FILMS; MIRAMAX FILM CORP., - Defendants, - - NO LIMIT FILMS LLC, - Defendant-Appellee. - - No. 03-5738 - BRIDGEPORT MUSIC, INC.; SOUTHFIELD MUSIC, INC.; - - NINE RECORDS, INC., - Plaintiffs-Appellants, - WESTBOUND RECORDS, INC., - Plaintiff, - - v. - - - DIMENSION FILMS, et al., - Defendants, - NO LIMIT FILMS LLC, - Defendant-Appellee. - - N Appeal from the United States District Court for the Middle District of Tennessee at Nashville. No. 01-00412—Thomas A. Higgins, District Judge. Argued: March 28, 2005 Decided and Filed: June 3, 2005 Before: GUY and GILMAN, Circuit Judges; BARZILAY, Judge.* * The Honorable Judith M. Barzilay, Judge, United States Court of International Trade, sitting by designation. 1 Nos. 02-6521; 03-5738 Bridgeport Music et al. v. Dimension Films et al. Page 2 _________________ COUNSEL ARGUED: Richard S. Busch, KING & BALLOW, Nashville, Tennessee, for Appellants. Robert L. Sullivan, LOEB & LOEB, Nashville, Tennessee, for Appellee. ON BRIEF: Richard S. Busch, D’Lesli M. Davis, KING & BALLOW, Nashville, Tennessee, for Appellants. Robert L. Sullivan, John C. Beiter, LOEB & LOEB, Nashville, Tennessee, for Appellee. Marjorie Heins, BRENNAN CENTER FOR JUSTICE AT NYU SCHOOL OF LAW, New York, New York, Paul M. Smith, JENNER & BLOCK, Washington, D.C., Fred von Lohmann, ELECTRONIC FRONTIER FOUNDATION, San Francisco, California, Todd M. Gascon, LAW OFFICE OF TODD GASCON, San Francisco, California, for Amici Curiae. -

BOONE-DISSERTATION.Pdf

Copyright by Christine Emily Boone 2011 The Dissertation Committee for Christine Emily Boone Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Mashups: History, Legality, and Aesthetics Committee: James Buhler, Supervisor Byron Almén Eric Drott Andrew Dell‘Antonio John Weinstock Mashups: History, Legality, and Aesthetics by Christine Emily Boone, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2011 Acknowledgements I want to first acknowledge those people who had a direct influence on the creation of this document. My brother, Philip, introduced me mashups a few years ago, and spawned my interest in the subject. Dr. Eric Drott taught a seminar on analyzing popular music where I was first able to research and write about mashups. And of course, my advisor, Dr. Jim Buhler has given me immeasurable help and guidance as I worked to complete both my degree and my dissertation. Thank you all so much for your help with this project. Although I am the only author of this dissertation, it truly could not have been completed without the help of many more people. First I would like to thank all of my professors, colleagues, and students at the University of Texas for making my time here so productive. I feel incredibly prepared to enter the field as an educator and a scholar thanks to all of you. I also want to thank all of my friends here in Austin and in other cities. -

The De Minimis Requirement As a Safety Valve: Copyright, Creativity, and the Sampling of Sound Recordings

39546-nyu_92-4 Sheet No. 252 Side A 10/12/2017 08:00:42 \\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\92-4\NYU415.txt unknown Seq: 1 11-OCT-17 13:27 THE DE MINIMIS REQUIREMENT AS A SAFETY VALVE: COPYRIGHT, CREATIVITY, AND THE SAMPLING OF SOUND RECORDINGS CHRISTOPHER WELDON* INTRODUCTION ................................................. 1262 R I. SAMPLING AND THE LAW ............................... 1265 R A. Sampling and Its Importance ........................ 1265 R B. Why Sampling Raises Copyright Issues.............. 1268 R C. The De Minimis Requirement ....................... 1271 R D. How the De Minimis Requirement Furthers Creativity ........................................... 1273 R 1. Why Copyright Can Threaten Musical Creativity ....................................... 1273 R 2. The De Minimis Requirement as a Safety Valve . 1278 R II. CIRCUIT SPLIT .......................................... 1280 R A. Bridgeport .......................................... 1280 R B. VMG Salsoul ....................................... 1284 R III. THE DE MINIMIS REQUIREMENT SHOULD APPLY TO THE SAMPLING OF SOUND RECORDINGS ................ 1286 R A. Why Do We Have Copyright? ...................... 1286 R B. Statutory Text and Structure......................... 1288 R 39546-nyu_92-4 Sheet No. 252 Side A 10/12/2017 08:00:42 C. Legislative History .................................. 1291 R D. Policy ............................................... 1294 R 1. Alternatives to Unlicensed Sampling Fall Short . 1294 R a. Recreating the Sound ....................... 1295 R b. Licensing -

Motwon/Disco/Soul/Funk

MOTWON/DISCO/SOUL/FUNK Ain’t No Mountain High Enough - Marvin Gaye Ain’t No Sunshine - Bill Withers Celebration - Kool & The Gang Dock Of The Bay - Otis Redding Easy Like Sunday Morning - The Commodores I Can See Clearly now - Johnny Nash Ladies Night-Kool & The Gang Let’s Get It On - Marvin Gaye Let’s Stay Together - Al Green Mustang Sally - Wilson Picket My Girl - The Temptations Proud Mary-Tina Turner September - Earth, Wind, & Fire Signed Sealed Delivered-Stevie Wonder Superstition - Stevie Wonder What’s Going On - Marvin Gaye 80s Africa - Toto All Night Long - Lionel Richie Call Me Al - Paul Simon Dancing In The Dark - Bruce Springsteen Don’t Stop Believing Journey Drive - The Cars Everybody Wants To Rule The World - Tears For Fears Footloose - Footloose Soundtrack Friday I’m In Love - The Cure Glory Days - Bruce Springsteen Head Over Heals - Tears For Fears How Soon Is Now - The Smiths Hungry Like The Wolf - Duran Duran Jack And Diane - John Cougar Just like Heaven - The Cure Living On A Prayer - Bon Jovi Love Song - The Cure New Sensation - INXS Pour Some Sugar On Me - Def Leppard Rosanna - Toto Sledgehammer - Peter Gabriel Still Haven’t Found What I'm Looking For - U2 Tempted - Squeeze This Charming Man - The Smiths What I Like About You - The Romantics Where The Streets Have No Name - U2 Wrapped Around Your Finger - The Police You Make My Dreams Come True - Hall & Oates CLASSIC ROCK American Girl - Tom Petty Bennie And The Jets - Elton John Black Magic Woman - Santana Born In The USA - Bruce Springsteen Born To Run - Bruce Springsteen -

Music Sampling and Copyright Law

CACPS UNDERGRADUATE THESIS #1, SPRING 1999 MUSIC SAMPLING AND COPYRIGHT LAW by John Lindenbaum April 8, 1999 A Senior Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My parents and grandparents for their support. My advisor Stan Katz for all the help. My research team: Tyler Doggett, Andy Goldman, Tom Pilla, Arthur Purvis, Abe Crystal, Max Abrams, Saran Chari, Will Jeffrion, Mike Wendschuh, Will DeVries, Mike Akins, Carole Lee, Chuck Monroe, Tommy Carr. Clockwork Orange and my carrelmates for not missing me too much. Don Joyce and Bob Boster for their suggestions. The Woodrow Wilson School Undergraduate Office for everything. All the people I’ve made music with: Yamato Spear, Kesu, CNU, Scott, Russian Smack, Marcus, the Setbacks, Scavacados, Web, Duchamp’s Fountain, and of course, Muffcake. David Lefkowitz and Figurehead Management in San Francisco. Edmund White, Tom Keenan, Bill Little, and Glenn Gass for getting me started. My friends, for being my friends. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction.....................................................................................……………………...1 History of Musical Appropriation........................................................…………………6 History of Music Copyright in the United States..................................………………17 Case Studies....................................................................................……………………..32 New Media......................................................................................……………………..50 -

Axis-Parents-Guide-To-Drake.Pdf

Drake “Drake is an interpreter, in other words, of the people he is trying to reach—an artist who can write lyrics that wide swaths of listeners will want to take ownership of and hooks that we will all want to sing to ourselves as we walk down the street. —Leon Neyfakh, “Peak Drake,” The FADER Does Drake have you in your feelings about how much your kids are listening to him? John Lennon famously said the Beatles were bigger than Jesus, but Aubrey Graham, aka Drake aka Drizzy, is now the best-selling solo male artist of all time. He has surpassed Elvis and Eminem, with over $218,000,000 in total record sales. Not only that, he was Billboard’s 2018 Top Artist and Spotify’s most-streamed artist, track, and album of 2018. Described by one writer as having “the Midas touch when it comes to making hits and singles,” it seems as though everything Drake does is successful. He appeals to those who like “harder” rap, but still excites a One Direction level of infatuation in young girls. Other rappers can take shots at his son and his parents [warning: strong language] without doing real damage to his career. He’s able to transform up-and-coming artists into superstars just by featuring them on his albums or being featured on theirs. With all of his influence on both his fans and the culture at large, it’s important to understand who Drake is, what he stands for, and what he’s teaching, both explicitly and implicitly, the people who listen to him. -

Please Note This Is a Sample Song List, Designed to Show the Style and Range of Music the Band Typically Performs

Please note this is a sample song list, designed to show the style and range of music the band typically performs. This is the most comprehensive list available at this time; however, the band is NOT LIMITED to the selections below. Please ask your event producer if you have a specific song request that is not listed. MSR SONG LIST TOP 40 AND DANCE HITS Adele Hello Rolling in the Deep Someone Like You Alicia Keys Underdog Andra Day Rise Up Ariana Grande 7 Rings Breathin Problems Thank You Next Beyonce Crazy in Love Halo Love on Top Single Ladies The Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling Blink 182 All the Small Things Britney Spears Baby One More Time Bruno Mars 24K Magic Finesse Just the Way You Are Locked Out of Heaven That's What I Like Treasure Uptown Funk Cardi B I Like It Bodak Yellow Carly Rae Jepsen Call Me Maybe Calvin Harris This is What You Came For Camila Cabello Havana Cee Lo Green Forget You The Chainsmokers Closer Don’t Let Me Down Chris Brown Look at Me Now Clean Bandit Rather Be Echosmith Cool Kids Cupid Cupid Shuffle Daft Punk Get Lucky David Guetta Titanium Demi Lovato Neon Lights Desiigner Panda DNCE Cake by the Ocean Drake God’s Plan Hold on We're Going Home Hotline Bling One Dance Toosie Slide Ed Sheeran Perfect Shape of You Thinking Out Loud Ellie Goulding Burn Fetty Wap My Way Fifth Harmony Work from Home Flo Rida Low Ginuwine Pony Gnarls Barkley Crazy Gotye Somebody That I Used to Know Halsey Without Me Icona Pop I Love It Iggy Azalea Fancy Imagine Dragons Radioactive Jason Derulo Talk Dirty to Me The Other Side Want -

Drake View Album Download Drake View Album Download

drake view album download Drake view album download. Drake Views Updated Download album, stream full hq songs | Pc mobile versions, download Drake Views Direct album. Drake's fourth album sounds claustrophobic and too long and weirdly monotonous, yet a few great moments are triggered by the occasional tweaks in the mix. On July 31, 2015, the track was recorded by Nineteen85 as the album's lead single "Hotline Bling" was released. 'Hotline Bling' was included as the bonus track on the record, despite the song being released as the official lead single for Views. VIEWS is the name of the record, but its viewpoint is distinctly singular. In a recent, toothless interview, Drake told Zane Lowe, differentiating VIEWS from his previous work, "This album, I'm very proud to say, is just, I feel like I told everyone how I really feel." This may sound like a ludicrous distinction, but it's appropriate, and it suggests why this album sounds more like a claustrophobic mindfuck than a communal catharsis. There's never any doubt that Drake is the star of his own show. Artist: Drake Album: Views (2016) Genre: Hip-Hop. Track list: 01. Keep the Family Close 02. 9 03. U With Me? 04. Feel No Ways 05. Hype 06. Weston Road Flows 07. Redemption 08. With You (feat. PARTYNEXTDOOR) 09. Faithful (feat. love-vendor C & dvsn) 10. Still Here 11. Controlla 12. One Dance (feat. Wizkid & Kyla) 13. Grammys (feat. Future) 14. Childs Play 15. Pop Style 16. Too Good (feat. Rihanna) 17. Summers Over Interlude 18. Fire & Desire 19. -

The Downhill Battle to Copyright Sonic Ideas in Bridgeport Music

Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment & Technology Law Volume 7 Issue 3 Issue 3 - Summer 2005 Article 7 2005 The Downhill Battle to Copyright Sonic Ideas in Bridgeport Music Matthew S. Garnett Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/jetlaw Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Matthew S. Garnett, The Downhill Battle to Copyright Sonic Ideas in Bridgeport Music, 7 Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment and Technology Law 509 (2020) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/jetlaw/vol7/iss3/7 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment & Technology Law by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. [B~yMrndepotic [By Matthew S. Garnett*]I he digital sampling controversy is right?6 "the student author's favorite The Bridgeport Music court responded dead horse."' Over the past de- with an iron gavel: "Get a license or do not cade, more than 100 legal articles, sample." 7 The court interpreted §114(b) of commentaries and student notes the Copyright Act of 1976 ("Copyright Act") have dealt with digital sampling to prohibit any unauthorized sampling where 2 and its relation to copyright law. "the actual sounds [in the original] recording In addition, the various constituencies in are rearranged, remixed, or otherwise altered the music industry, such as artists, compos- in sequence or quality."8 Consequently, the de- ers, producers, and recording executives, have fensive tools of copyright infringement, such "..