Nuclear Weapons Testing in the Age of Atmospheric Anxiety, 1945-1963

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2012 04 Newsletter

United States Atmospheric & Underwater Atomic Weapon Activities National Association of Atomic Veterans, Inc. 1945 “TRINITY“ “Assisting America’s Atomic Veterans Since 1979” ALAMOGORDO, N. M. Website: www.naav.com E-mail: [email protected] 1945 “LITTLE BOY“ HIROSHIMA, JAPAN R. J. RITTER - Editor April, 2012 1945 “FAT MAN“ NAGASAKI, JAPAN 1946 “CROSSROADS“ BIKINI ISLAND 1948 “SANDSTONE“ ENEWETAK ATOLL 1951 “RANGER“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1951 “GREENHOUSE“ ENEWETAK ATOLL 1951 “BUSTER – JANGLE“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1952 “TUMBLER - SNAPPER“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1952 “IVY“ ENEWETAK ATOLL 1953 “UPSHOT - KNOTHOLE“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1954 “CASTLE“ BIKINI ISLAND 1955 “TEAPOT“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1955 “WIGWAM“ OFFSHORE SAN DIEGO 1955 “PROJECT 56“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1956 “REDWING“ ENEWETAK & BIKINI 1957 “PLUMBOB“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1958 “HARDTACK-I“ ENEWETAK & BIKINI 1958 “NEWSREEL“ JOHNSTON ISLAND 1958 “ARGUS“ SOUTH ATLANTIC 1958 “HARDTACK-II“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1961 “NOUGAT“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1962 “DOMINIC-I“ CHRISTMAS ISLAND JOHNSTON ISLAND 1965 “FLINTLOCK“ AMCHITKA, ALASKA 1969 “MANDREL“ AMCHITKA, ALASKA 1971 “GROMMET“ AMCHITKA, ALASKA 1974 “POST TEST EVENTS“ ENEWETAK CLEANUP ------------ “ IF YOU WERE THERE, YOU ARE AN ATOMIC VETERAN “ The Newsletter for America’s Atomic Veterans COMMANDER’S COMMENTS knowing the seriousness of the situation, did not register any Outreach Update: First, let me extend our discomfort, or dissatisfaction on her part. As a matter of fact, it thanks to the membership and friends of NAAV was kind of nice to have some of those callers express their for supporting our “outreach” efforts over the thanks for her kind attention and assistance. We will continue past several years. It is that firm dedication to to insure that all inquires, along these lines, are fully and our Mission-Statement that has driven our adequately addressed. -

Grappling with the Bomb: Britain's Pacific H-Bomb Tests

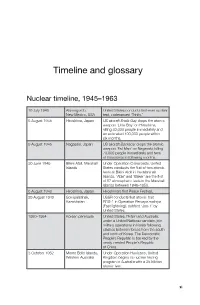

Timeline and glossary Nuclear timeline, 1945–1963 16 July 1945 Alamogordo, United States conducts first-ever nuclear New Mexico, USA test, codenamed ‘Trinity .’ 6 August 1945 Hiroshima, Japan US aircraft Enola Gay drops the atomic weapon ‘Little Boy’ on Hiroshima, killing 80,000 people immediately and an estimated 100,000 people within six months . 9 August 1945 Nagasaki, Japan US aircraft Bockscar drops the atomic weapon ‘Fat Man’ on Nagasaki, killing 70,000 people immediately and tens of thousands in following months . 30 June 1946 Bikini Atoll, Marshall Under Operation Crossroads, United Islands States conducts the first of two atomic tests at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands. ‘Able’ and ‘Baker’ are the first of 67 atmospheric tests in the Marshall Islands between 1946–1958 . 6 August 1948 Hiroshima, Japan Hiroshima’s first Peace Festival. 29 August 1949 Semipalatinsk, USSR conducts first atomic test Kazakhstan RDS-1 in Operation Pervaya molniya (Fast lightning), dubbed ‘Joe-1’ by United States . 1950–1954 Korean peninsula United States, Britain and Australia, under a United Nations mandate, join military operations in Korea following clashes between forces from the south and north of Korea. The Democratic People’s Republic is backed by the newly created People’s Republic of China . 3 October 1952 Monte Bello Islands, Under Operation Hurricane, United Western Australia Kingdom begins its nuclear testing program in Australia with a 25 kiloton atomic test . xi GRAPPLING WITH THE BOMB 1 November 1952 Bikini Atoll, Marshall United States conducts its first Islands hydrogen bomb test, codenamed ‘Mike’ (10 .4 megatons) as part of Operation Ivy . -

Trinity and Beyond: the Atomic Bomb Movie

Trinity and Beyond: The Atomic Bomb Movie 1. Why did scientists detonate 100 tons of TNT be- 9. How many died in Hiroshima? 20. How heavy was the housing that contained the fore they tested their bombs? Mike test bomb? 10. How many buildings were destroyed? 2. Who was put in charge of the Manhattan Project? 21. During the 1953 Nevada desert tests, why did the smaller yield bomb cause more damage than the 11. How many died in Nagasaki? larger yield bomb? 3. Was the scientist Edward Teller at first in favor of the bomb project? 12. How many were injured? 22. What were the scientists studying when they ex- ploded bombs in the ocean off of San Diego? 4. Did he ever regret working on the bombs? 13. What percent of the buildings were destroyed? 23. On later Pacific Island tests, why were floating 5. When the first test bomb exploded at the Trinity barges needed to carry the bombs? site in New Mexico, what were the values associated 14. During Operation Crossroads, which caused with each of the following? more damage; the airdrop, or the underwater explo- sion? 24. How high up was the Teak test shot detonated? a) temperature: b) pressure: 15. What was the purpose of Operation Sandstone? 25. What happened in the atmosphere as a result? c) distance at which a person would go temporarily blind: d) number of times greater than the explosion of 100 16. In what year did Russia first test an atomic 26. How far away were these effects felt, and how tons of TNT: bomb? long did they last? 6. -

Journal 21 – Seminar – Malaya, Korea & Kuwait

ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY JOURNAL 21 2 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society. First published in the UK in 2000 Copyright 200: Royal Air Force Historical Society All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. ISSN 1361-4231 Printed by Fotodirect Ltd Enterprise Estate, Crowhurst Road Brighton, East Sussex BN1 8AF Tel 01273 563111 3 ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY President Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Michael Beetham GCB CBE DFC AFC Vice-President Air Marshal Sir Frederick Sowrey KCB CBE AFC Committee Chairman Air Vice-Marshal N B Baldwin CB CBE Vice-Chairman Group Captain J D Heron OBE General Secretary Wing Commander C G Jefford MBE BA Membership Secretary Dr Jack Dunham PhD CPsychol AMRAeS Treasurer Desmond Goch Esq FCAA Members *J S Cox BA MA *Dr M A Fopp MA FMA FIMgt *Group Captain P J Greville RAF Air Commodore H A Probert MBE MA Editor, Publications Derek H Wood Esq AFRAeS Publications Manager Roy Walker Esq ACIB *Ex Officio 4 CONTENTS Malaya, Korea and Kuwait seminar Malaya 5 Korea 59 Kuwait 90 MRAF Lord Tedder by Dr V Orange 145 Book Reviews 161 5 RAF OPERATIONS 1948-1961 MALAYA – KOREA – KUWAIT WELCOMING ADDRESS BY SOCIETY CHAIRMAN Air Vice-Marshal Nigel Baldwin It is a pleasure to welcome all of you today. -

Satellite Meteorology in the Cold War Era: Scientific Coalitions and International Leadership 1946-1964

SATELLITE METEOROLOGY IN THE COLD WAR ERA: SCIENTIFIC COALITIONS AND INTERNATIONAL LEADERSHIP 1946-1964 A Dissertation Presented to The Academic Faculty By Angelina Long Callahan In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in History and Sociology of Technology and Science Georgia Institute of Technology December 2013 Copyright © Angelina Long Callahan 2013 SATELLITE METEOROLOGY IN THE COLD WAR ERA: SCIENTIFIC COALITIONS AND INTERNATIONAL LEADERSHIP 1946-1964 Approved by: Dr. John Krige, Advisor Dr. Leo Slater School of History, Technology & History Office Society Code 1001.15 Georgia Institute of Technology Naval Research Laboratory Dr. James Fleming Dr. Steven Usselman School of History, Technology & School of History, Technology & Society Society Colby College Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Kenneth Knoespel Date Approved: School of History, Technology & 6 November 2013 Society Georgia Institute of Technology ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I submit this dissertation mindful that I’ve much left to do and much left to learn. Thus, lacking more elegant phrasing, I dedicate this to anyone who has set aside their own work to educate me. All of you listed below are extremely talented and because of that, managing substantial workloads. In spite of that, you have each been generous with your insight over the years and I am grateful for every meeting, email, and gesture of support you have shown. First, I want to thank my dissertation committee. I am extremely proud to claim each of you as a mentor. Please know how grateful I am for your patience and constructive criticism with this work in progress as it evolved milestone by milestone. -

Space Rock, the Popular Music Inspired by the Stars Above Us

SPACE ROCK, THE POPULAR MUSIC INSPIRED BY THE STARS ABOVE US JARKKO MATIAS MERISALO 79222N ASTRONOMICAL VIEW OF THE WORLD PART B S-92.3299AALTO UNIVERSITY 0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of contents ................................................................................................................. 1 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................... 2 2. What is space rock and how it was born? ..................................................................... 3 3. The Golden era ............................................................................................................. 5 3.1. Significant artists and songs to remember ................................................................ 5 3.2. Masks and Glitter – Spacemen and rock characters ................................................. 7 4. Modern times .............................................................................................................. 10 5. Conclusions ................................................................................................................. 12 6. References .................................................................................................................. 13 7. Appendices ................................................................................................................. 14 1. INTRODUCTION When the Soviets managed to launch “Sputnik 1”, the first man-made object to the Earth’s orbit in November 1957, -

Tomoe Otsuki

Volume 13 | Issue 32 | Number 2 | Article ID 4356 | Aug 10, 2015 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus The Politics of Reconstruction and Reconciliation in U.S-Japan Relations—Dismantling the Atomic Bomb Ruins of Nagasaki’s Urakami Cathedral Tomoe Otsuki Abstract: This paper explores the politics surrounding the dismantling of the ruins of Nagasaki’s Urakami Cathedral. It shows how U.S-Japan relations in the mid-1950s shaped the 1958 decision by the Catholic community of Urakami to dismantle and subsequently to reconstruct the ruins. The paper also assesses the significance of the struggle over the ruins of the Urakami Cathedral for understanding the respective responses to atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It further casts new light on the wartime role of the Catholic Church and of Nagai Takashi. Keywords: Nagasaki, Atomic Bomb, Urakami Cathedral, the People-to-People program, Lucky Dragon # 5 incident, Japanese antinuclear movement, the peaceful use of nuclear energy, sister city relation between Nagasaki and St. Paul, U.S.-Japan Security Alliance. The two photographs below depict the remnants of the Urakami Cathedral following the atomic bombing of Nagasaki. Both were taken in 1953 by Takahara Itaru, a former Mainichi Shimbun photographer as well as a Remnants of the Southern Wall and statues of the Nagasaki hibakusha. Most of the children saints of Urakami Cathedral playing beside the ruins were born after the Photo courtesy of Takahara Itaru atomic bombing and grew up in Urakami’s atomic field. Takahara’s photographs capture the remnants of the cathedral in shaping the Children play in remnants of belfry of Urakami postwar landscape and lives of people in and Cathedral 1 around Urakami. -

Smithsonian and the Enola

An Air Force Association Special Report The Smithsonian and the Enola Gay The Air Force Association The Air Force Association (AFA) is an independent, nonprofit civilian organiza- tion promoting public understanding of aerospace power and the pivotal role it plays in the security of the nation. AFA publishes Air Force Magazine, sponsors national symposia, and disseminates infor- mation through outreach programs of its affiliate, the Aerospace Education Founda- tion. Learn more about AFA by visiting us on the Web at www.afa.org. The Aerospace Education Foundation The Aerospace Education Foundation (AEF) is dedicated to ensuring America’s aerospace excellence through education, scholarships, grants, awards, and public awareness programs. The Foundation also publishes a series of studies and forums on aerospace and national security. The Eaker Institute is the public policy and research arm of AEF. AEF works through a network of thou- sands of Air Force Association members and more than 200 chapters to distrib- ute educational material to schools and concerned citizens. An example of this includes “Visions of Exploration,” an AEF/USA Today multi-disciplinary sci- ence, math, and social studies program. To find out how you can support aerospace excellence visit us on the Web at www. aef.org. © 2004 The Air Force Association Published 2004 by Aerospace Education Foundation 1501 Lee Highway Arlington VA 22209-1198 Tel: (703) 247-5839 Produced by the staff of Air Force Magazine Fax: (703) 247-5853 Design by Guy Aceto, Art Director An Air Force Association Special Report The Smithsonian and the Enola Gay By John T. Correll April 2004 Front cover: The huge B-29 bomber Enola Gay, which dropped an atomic bomb on Japan, is one of the world’s most famous airplanes. -

Computer Models, Climate Data, and the Politics of Global Warming (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2010)

Complete bibliography of all items cited in A Vast Machine: Computer Models, Climate Data, and the Politics of Global Warming (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2010) Paul N. Edwards Caveat: this bibliography contains occasional typographical errors and incomplete citations. Abbate, Janet. Inventing the Internet. Inside Technology. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1999. Abbe, Cleveland. “The Weather Map on the Polar Projection.” Monthly Weather Review 42, no. 1 (1914): 36-38. Abelson, P. H. “Scientific Communication.” Science 209, no. 4452 (1980): 60-62. Aber, John D. “Terrestrial Ecosystems.” In Climate System Modeling, edited by Kevin E. Trenberth, 173- 200. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992. Ad Hoc Study Group on Carbon Dioxide and Climate. “Carbon Dioxide and Climate: A Scientific Assessment.” (1979): Air Force Data Control Unit. Machine Methods of Weather Statistics. New Orleans: Air Weather Service, 1948. Air Force Data Control Unit. Machine Methods of Weather Statistics. New Orleans: Air Weather Service, 1949. Alaka, MA, and RC Elvander. “Optimum Interpolation From Observations of Mixed Quality.” Monthly Weather Review 100, no. 8 (1972): 612-24. Edwards, A Vast Machine Bibliography 1 Alder, Ken. The Measure of All Things: The Seven-Year Odyssey and Hidden Error That Transformed the World. New York: Free Press, 2002. Allen, MR, and DJ Frame. “Call Off the Quest.” Science 318, no. 5850 (2007): 582. Alvarez, LW, W Alvarez, F Asaro, and HV Michel. “Extraterrestrial Cause for the Cretaceous-Tertiary Extinction.” Science 208, no. 4448 (1980): 1095-108. American Meteorological Society. 2000. Glossary of Meteorology. http://amsglossary.allenpress.com/glossary/ Anderson, E. C., and W. F. Libby. “World-Wide Distribution of Natural Radiocarbon.” Physical Review 81, no. -

Telstar – a Philatelic History the Communication Revolution Began with This Satellite Series

Telstar – A Philatelic History The Communication Revolution Began with this Satellite Series Don Hillger SU5200, Garry Toth, and Sig Bette SU-1063 This Telstar article appeared in the October 2012 issue of American Philatelic Society’s “American Philatelist” magazine, and is reprinted with the permission of Editor Barbara Boal Telstar-1 made history for our interested Space Unit members. over fifty years ago on July 11, 1962, one day after its launch, when it transmitted the first television signals across the Atlantic Ocean,1 between the United States of America and France. Al- though not the first active communications satellite,2 it became a popular and recognizable name in the new world of artificial satellites. Telstar even spawned a musical composition titled “Telstar,” performed by The Tornados, an instrumental band A second set of common design stamps of the early 1960s. Their recording was was issued to commemorate the same the first single by a British band to event, but the event is noted as the “first reach number one in the United States, television transmission between Europe later becaming a number one hit in the and America,” versus “first television United Kingdom as well. Written and transmission by satellite” on the previous produced by Joel Meek, the spacey issue. On all of these stamps the cities of sounds of the recording were produced Andover (Maine) and Pleumeur-Bodou by a clavioline, a keyboard instrument (France) are identified, with Telstar shown with distinctive electronic sounds. The in orbit, relaying signals between the song was also recorded by other bands, two locations. -

Great Instrumental

I grew up during the heyday of pop instrumental music in the 1950s and the 1960s (there were 30 instrumental hits in the Top 40 in 1961), and I would listen to the radio faithfully for the 30 seconds before the hourly news when they would play instrumentals (however the first 45’s I bought were vocals: Bimbo by Jim Reeves in 1954, The Ballad of Davy Crockett with the flip side Farewell by Fess Parker in 1955, and Sixteen Tons by Tennessee Ernie Ford in 1956). I also listened to my Dad’s 78s, and my favorite song of those was Raymond Scott’s Powerhouse from 1937 (which was often heard in Warner Bros. cartoons). and to records that my friends had, and that their parents had - artists such as: (This is not meant to be a complete or definitive list of the music of these artists, or a definitive list of instrumental artists – rather it is just a list of many of the instrumental songs I heard and loved when I was growing up - therefore this list just goes up to the early 1970s): Floyd Cramer (Last Date and On the Rebound and Let’s Go and Hot Pepper and Flip Flop & Bob and The First Hurt and Fancy Pants and Shrum and All Keyed Up and San Antonio Rose and [These Are] The Young Years and What’d I Say and Java and How High the Moon), The Ventures (Walk Don't Run and Walk Don’t Run ‘64 and Perfidia and Ram-Bunk-Shush and Diamond Head and The Cruel Sea and Hawaii Five-O and Oh Pretty Woman and Go and Pedal Pusher and Tall Cool One and Slaughter on Tenth Avenue), Booker T. -

Rewards and Penalties of Monitoring the Earth

rg o me 23 (c)1998 by Annual Reviews. u September 11, 1998P1: H 13:40 Annual Reviews AR064-00 AR64-FrontisP-II Annu. Rev. Energy. Environ. 1998.23:25-82. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews. Reprinted, with permission, from the Annual Review of Energy and the Environment, Vol Reprinted, with permission, from the Annual Review of Energy and Environment, P1: PSA/spd P2: PSA/plb QC: PSA/KKK/tkj T1: PSA September 29, 1998 10:3 Annual Reviews AR064-02 Annu. Rev. Energy Environ. 1998. 23:25–82 Copyright c 1998 by Annual Reviews. All rights reserved rg o REWARDS AND PENALTIES OF MONITORING THE EARTH Charles D. Keeling me 23 (c)1998 by Annual Reviews. u Scripps Institution of Oceanography, La Jolla, California 92093-0220 KEY WORDS: monitoring carbon dioxide, global warming ABSTRACT When I began my professional career, the pursuit of science was in a transition from a pursuit by individuals motivated by personal curiosity to a worldwide enterprise with powerful strategic and materialistic purposes. The studies of the Earth’s environment that I have engaged in for over forty years, and describe in this essay, could not have been realized by the old kind of science. Associated with the new kind of science, however, was a loss of ease to pursue, unfettered, one’s personal approaches to scientific discovery. Human society, embracing science for its tangible benefits, inevitably has grown dependent on scientific discoveries. It now seeks direct deliverable results, often on a timetable, as compensation for public sponsorship. Perhaps my experience in studying the Earth, initially with few restrictions and later with increasingly sophisticated interaction with government sponsors and various planning committees, will provide a perspective on this great transition from science being primarily an intellectual pastime of private persons to its present status as a major contributor to the quality of human life and the prosperity of nations.