Vernacular Architecture at a Contemporary Dene Hunting Camp1 by Robert R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural Information TIPI Medicine Wheel TIPI Making Instructions Kit

TIPI Making Instructions Kit consist of: Cultural information 4 pony beads It is important to note that just like all traditional teachings, 1 long tie certain beliefs and values differ from region to region. 2 small ties 1 concho, 1 elastic 4 tipi posts TIPI 7 small sticks 1 round wood The floor of the tipi represents the earth on which we 1 bed, 1 note bag live, the walls represent the sky and the poles represent (with paper) the trails that extend from the earth to the spirit world (Dakota teachings). 1. Place tipi posts in holes (if needed use elastic to gather Tipis hold special significance among many different nations posts at top). and Aboriginal cultures across North America. They not only have cultural significance, but also serve practical purposes 2. Stick the double sided tape to the outside of the base (particularly when nations practiced traditional ways of (alternatively use glue or glue gun). living like hunting and gathering). Tipis provide shelter, warmth, and family and community connectedness. They 3. Stick the leather to the board, starting with the side are still used today for ceremonies and other purposes. without the door flap. Continue all the way around There is special meaning behind their creation and set up. (if needed cut the excess material). For spiritual purposes, the tipi’s entrance faces the East 4. Press all the way around a few times, to make sure the and the back faces the West. This is to symbolize the rising leather is well stuck onto the board. and setting of the sun and the cardinal directions. -

Tipi Instructions

Tipi Instructions Hello and thanks for buying one of our Tipi Tents. Here are the instructions for the best way to put it up, take it down and how to store when not in use. We’ve provided a step-by-step picture guide for you to follow along with the written instructions. At the bottom of these instructions we’ve added some advice and tips on how to get years of good service out of your tent by looking after it properly. Enjoy! And don’t hesitate to contact us if you have any questions, good ideas or better ways of doing it. Once you’ve erected your tent, we would love to see your Boutique Camping pictures, so please send them to us at [email protected]. They may even feature on our blog or Facebook page! Putting up a Tipi Tent Some general advice • We advise having 2 people to erect the tent, as it will of course simplify the process. By all means, you can put it up on your own, but of course the more the merrier, easier and quicker! • Find a flat piece of land, with ample space to comfortably put up your tent remembering to include room for the guy ropes • To prevent damaging the groundsheet, remove all sharp objects from the area. Things like stones and roots etc • Be careful when creating tension with the guy ropes, always try to keep the tension even, and never over do it. Be firm but gentle. • Before you peg out the tent, make sure all zips are closed, and check again when you adjust the guy ropes • Peg out the guy ropes in line with the tent seams How to Put Up Your Tipi A1)Open all bags and lay out all parts. -

Re-Creating Indigenous Architectural Knowledge in Arctic Canada and Norawy

Protection of cultural heritage 9 (2020) 10.35784/odk.2085 RE-CREATING INDIGENOUS ARCHITECTURAL KNOWLEDGE IN ARCTIC CANADA AND NORAWY MACKIN Nancy 1 1 dr Nancy Mackin, University of British Columbia and University of Victoria, Canada https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5427-3202 ABSTRACT: Long resident peoples including Gwich’in, Inuvialuit, Copper Inuit, and Sami, Coast Salish and others have learned over countless generations of observation and experimentation to construct place-specific, biomimetic architecture. To learn more about the heritage value of long-resident peoples’ architecture, and to discover how their architecture can selectively inform adaptable architecture of the future. we engaged Inuit and First Nations knowledge-holders and young people in re-creating tradition-based shelters and housing. During the reconstructions, children and Elders alike expressed their enthusiasm and pride in the inventiveness and usefulness of their ancestral architectural wisdom. Several of the structures created during this research are still standing years later and continue to serve as emergency shelters for food harvesters. During extreme weather, the shelters contribute to a potentially widespread network of food harvester dwellings that would facilitate revitalization of traditional foodways. The re-creations indicate that building materials, forms, assembly technologies, and other considerations from the architecture of Indigenous peoples provide a valuable heritage resource for architects of the future. KEY WORDS: Indigenous, Arctic architecture, Inuit architecture, reconstructions, heritage 58 Nancy Mackin 1. Introduction and research questions Tradition-based shelters have always been part of life in the high Arctic, where sudden storms and extreme cold pose serious risks to food harvesters, scientists, and other people out on the land. -

New Mexico New Mexico

NEW MEXICO NEWand MEXICO the PIMERIA ALTA THE COLONIAL PERIOD IN THE AMERICAN SOUTHWEst edited by John G. Douglass and William M. Graves NEW MEXICO AND THE PIMERÍA ALTA NEWand MEXICO thePI MERÍA ALTA THE COLONIAL PERIOD IN THE AMERICAN SOUTHWEst edited by John G. Douglass and William M. Graves UNIVERSITY PRESS OF COLORADO Boulder © 2017 by University Press of Colorado Published by University Press of Colorado 5589 Arapahoe Avenue, Suite 206C Boulder, Colorado 80303 All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of Association of American University Presses. The University Press of Colorado is a cooperative publishing enterprise supported, in part, by Adams State University, Colorado State University, Fort Lewis College, Metropolitan State University of Denver, Regis University, University of Colorado, University of Northern Colorado, Utah State University, and Western State Colorado University. ∞ This paper meets the requirements of the ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). ISBN: 978-1-60732-573-4 (cloth) ISBN: 978-1-60732-574-1 (ebook) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Douglass, John G., 1968– editor. | Graves, William M., editor. Title: New Mexico and the Pimería Alta : the colonial period in the American Southwest / edited by John G. Douglass and William M. Graves. Description: Boulder : University Press of Colorado, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2016044391| ISBN 9781607325734 (cloth) | ISBN 9781607325741 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Spaniards—Pimería Alta (Mexico and Ariz.)—History. | Spaniards—Southwest, New—History. | Indians of North America—First contact with Europeans—Pimería Alta (Mexico and Ariz.)—History. -

Concrete Interstate Tipis of South Dakota (Constructed 1968-79) Meet the Criteria Consideration G Because of Their Exceptional Importance

NPS Form 10-900-a OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior Concrete Interstate TipisPut of South Here Dakota National Park Service Multiple Property Listing Name of Property National Register of Historic Places Multiple, South Dakota Continuation Sheet County and State Section number E Page 1 E. Statement of Historic Contexts NOTE: The terms “tipi,” “tepee,” and “teepee” are used interchangeably in both historical and popular documents. For consistency, the term “tipi” will be used in this document unless an alternate spelling is quoted directly. NOTE: The interstate tipis are not true tipis. They are concrete structures that imitate lodgepoles, or the lodgepoles framing the tipi structure. The lodgepoles interlock in a similar spiral fashion, as would a real tipi. An exact imitation of tipis would also have included smoke flap poles and covering. However, they have historically been referred to as tipis. This document will continue that tradition. List of Safety Rest Areas with Concrete Tipis in South Dakota Rest Area Location Year completed Comments (according to 1988 study) Spearfish: I-90 1977 Eastbound only Wasta: I-90 1968 Eastbound and Westbound Chamberlain: I-90 1976 Eastbound and West Salem: I-90 1968 East and Westbound Valley Springs (MN 1973 Eastbound only Border): I-90 Junction City 1979 Northbound and Southbound (Vermillion): I-29 Glacial Lakes (New 1978 Southbound only Effington): I-29 Introduction Between 1968 and 1979, nine concrete tipis were constructed at safety rest areas in South Dakota. Seven were constructed on Interstate 90 running east to west and two on Interstate 29 running north to south. -

Sustainable Features of Vernacular Architecture: Housing of Eastern Black Sea Region As a Case Study

arts Article Sustainable Features of Vernacular Architecture: Housing of Eastern Black Sea Region as a Case Study Burcu Salgın 1,*, Ömer F. Bayram 1, Atacan Akgün 1 and Kofi Agyekum 2 1 Department of Architecture, Erciyes University, Kayseri 38030, Turkey; [email protected] (Ö.F.B.); [email protected] (A.A.) 2 Department of Building Technology, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi 233, Ghana; agyekum.kofi[email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 22 May 2017; Accepted: 4 August 2017; Published: 17 August 2017 Abstract: The contributions of sustainability to architectural designs are steadily increasing in parallel with developments in technology. Although sustainability seems to be a new concept in today’s architecture, in reality, it is not. This is because, much of sustainable architectural design principles depend on references to vernacular architecture, and there are many examples found in different parts of the world to which architects can refer. When the world seeks for more sustainable buildings, it is acceptable to revisit the past in order to understand sustainable features of vernacular architecture. It is clear that vernacular architecture has a knowledge that matters to be studied and classified from a sustainability point of view. This work aims to demonstrate that vernacular architecture can contribute to improving sustainability in construction. In this sense, the paper evaluates specific vernacular housing in Eastern Black Sea Region in Turkey and their response to nature and ecology. In order to explain this response, field work was carried out and the vernacular architectural accumulation of the region was examined on site. -

The Sámi People and Their Culture the Sámi Or Saami Were Also Called Lapps Or Laplanders by the English

The Sámi people and their culture The Sámi or Saami were also called Lapps or Laplanders by the English. Sámi people consider the English terms derogatory. The Sámi are recognized as the only indigenous people of Europe. They have lived in Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia. Their origins are Finno‐Ugric, a Hungarian and Yugra (Urals) past, inhabiting the Sápmi region. Today, the region encompasses large parts of Norway and Sweden, northern parts of Finland, and the Murmansk Oblast (Kola Peninsula) of Russia. The Sámi people have their own language, culture and customs that differ from others around them. This has caused the Sámi social problems and culture clashes. As we learned from our Sámi culture presentation and a quote from ‐religiousstudiesproject.com the following: “The history between the Sámi and the Norwegian government has left a stain on the Sámi for generations: The Norwegianization policy undertaken by the Norwegian government from the 1850s up until the Second World War resulted in the apparent loss of Sami language and assimilation of the coastal Sami as an ethnically‐distinct people into the northern Norwegian population. Together with the rise of an ethno‐political movement since the 1970s, however, Sami culture has seen a revitalization of language, cultural activities, and ethnic identity (Brattland 2010:31).” Note: Suggested readings, ‐laits.utexas.edu, a 19‐part series by the University of Texas entitled “Sámi Culture.” The other reading is‐ unsr.vtaulicorpuz.org. It is a report by the United Nations on the rights of indigenous people such as the Sámi. Reindeer are the Sámi key element to how they live. -

Tent Inspection

Tent Guide Information referenced from the 2015 Frederick County Fire Prevention Code A Tent is defined as a structure, enclosure or shelter, with or without sidewalls or drops, constructed of fabric or pliable material supported by any manner except by air or the contents that it protects. All Tents: • A permit issued by the Frederick County Fire Marshal’s office shall be required for tents over 900 square feet not being used for recreational camping purposes. (Frederick County fire Prevention Code section 107.2 Permit Required.) • A detailed site and floor plan for tents with occupant load of 50 or more shall be required with each application for approval. The tent floor plan shall indicate details of means of egress, seating capacity, arrangement of seating and location and types of heating and electrical equipment. (Frederick County fire Prevention Code section 3103.6 Construction documents.) • An unobstructed fire break passageway or fire road not less than 12 feet wide and free from guy ropes or other obstructions shall be maintained on all sides of all tents unless otherwise approved by the fire code official. (Frederick County fire Prevention Code section 3103.8.6 Fire break.) • A certificate from an approved laboratory stating that the materials used in tent meet the flame- retardant criteria needed to pass NFPA Test Method 1 or Test Method 2. (Frederick County fire Prevention Code section 3104.2 Flame propagation performance treatment.) • Approved “No Smoking” signs shall be conspicuously posted. (Frederick County fire Prevention Code section 3104.6 Smoking.) • At least one 5lb. multipurpose 2A 10BC portable fire extinguisher shall be hung and tagged within 75 ft of travel distance. -

THE SUN, the MOON and FIRMAMENT in CHUKCHI MYTHOLOGY and on the RELATIONS of CELESTIAL BODIES and SACRIFICE Ülo Siimets

THE SUN, THE MOON AND FIRMAMENT IN CHUKCHI MYTHOLOGY AND ON THE RELATIONS OF CELESTIAL BODIES AND SACRIFICE Ülo Siimets Abstract This article gives a brief overview of the most common Chukchi myths, notions and beliefs related to celestial bodies at the end of the 19th and during the 20th century. The firmament of Chukchi world view is connected with their main source of subsistence – reindeer herding. Chukchis are one of the very few Siberian indigenous people who have preserved their religion. Similarly to many other nations, the peoples of the Far North as well as Chukchis personify the Sun, the Moon and stars. The article also points out the similarities between Chukchi notions and these of other peoples. Till now Chukchi reindeer herders seek the supposed help or influence of a constellation or planet when making important sacrifices (for example, offering sacrifices in a full moon). According to the Chukchi religion the most important celestial character is the Sun. It is spoken of as an individual being (vaúrgún). In addition to the Sun, the Creator, Dawn, Zenith, Midday and the North Star also belong to the ranks of special (superior) beings. The Moon in Chukchi mythology is a man and a being in one person. It is as the ketlja (evil spirit) of the Sun. Chukchi myths about several stars (such as the North Star and Betelgeuse) resemble to a great extent these of other peoples. Keywords: astral mythology, the Moon, sacrifices, reindeer herding, the Sun, celestial bodies, Chukchi religion, constellations. The interdependence of the Earth and celestial as well as weather phenomena has a special meaning for mankind for it is the co-exist- ence of the Sun and Moon, day and night, wind, rainfall and soil that creates life and warmth and provides the daily bread. -

Vernacular Architecture in Michoacán. Constructive Tradition As a Response to the Natural and Cultural Surroundings

Athens Journal of Architecture - Volume 2, Issue 4 – Pages 313-326 Vernacular Architecture in Michoacán. Constructive Tradition as a Response to the Natural and Cultural Surroundings By Eugenia Maria Azevedo-Salomao Luis Alberto Torres-Garibay† Various regions of Mexico (i.e., Michoacán) have a tradition in vernacular architecture with an important wealth heritage. Constructing in this way has a notable ecological quality that has benefits for its inhabitants and the natural and cultural surroundings. This work addresses the habitability of vernacular architecture in Michoacán, making the claim that the tradition of construction methods is anchored to the collective memory and the memory of the lived space. Therefore, memories express themselves as the truth of the past based in the present. In this way, the artisans of Michoacán gathered experience from past generations and distinguished themselves by the rational use of primary materials. With direct observation, surveys to users and literature based researches, selected examples of Michoacán are analyzed. The focus is on permanencies and transformations of the vernacular architecture of the region through the observation of social habits, uses, forms, construction, natural surrounding context and significance to society. The conclusion is reached by questioning why there is a gradual loss of vernacular heritage in the region. It is observed that a necessity for its permanence is required as well as the benefits of the implementation of new techniques that contribute to the regeneration of heritage buildings is emphasized. With sustainability in mind the incorporation of vernacular materials and construction methods together with contemporary solutions is also addressed. Introduction Vernacular architecture is the result of the process of collective creation in a geographical and cultural space. -

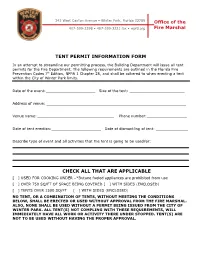

Tent & Events Under a Tent Permit Application

343 West Canton Avenue • Winter Park, Florida 32789 Office of the 407-599-3298 • 407-599-3231 fax • wpfd.org Fire Marshal TENT PERMIT INFORMATION FORM In an attempt to streamline our permitting process, the Building Department will issue all tent permits for the Fire Department. The following requirements are outlined in the Florida Fire Prevention Codes 7th Edition, NFPA 1 Chapter 25, and shall be adhered to when erecting a tent within the City of Winter Park limits. Date of the event: Size of the tent: Address of venue: Venue name: Phone number: _ Date of tent erection: Date of dismantling of tent: Describe type of event and all activities that the tent is going to be used for: CHECK ALL THAT ARE APPLICABLE [ ] USED FOR COOKING UNDER –*Butane fueled appliances are prohibited from use [ ] OVER 750 SQ/FT OF SPACE BEING COVERED [ ] WITH SIDES (ENCLOSED) [ ] TENTS OVER 1500 SQ/FT [ ] WITH SIDES (ENCLOSED) NO TENT, OR A COMBINATION OF TENTS, WITHOUT MEETING THE CONDITIONS BELOW, SHALL BE ERECTED OR USED WITHOUT APPROVAL FROM THE FIRE MARSHAL. ALSO, NONE SHALL BE USED WITHOUT A PERMIT BEING ISSUED FROM THE CITY OF WINTER PARK. ALL TENT(S) NOT COMPLING WITH THESE REQUIREMENTS, WILL IMMEDIATELY HAVE ALL WORK OR ACTIVITY THERE UNDER STOPPED. TENT(S) ARE NOT TO BE USED WITHOUT HAVING THE PROPER APPROVAL. TENTS USED FOR COOKING 1. Permits for all tents used to cook under, shall be submitted no later than five business days prior to the erection of the tents. An inspection at least 90 minutes prior to the cooking operations and subject to all fees per the City of Winter Park may be required. -

Log Cabin Studies: the Rocky Mountain Cabin, Log Cabin Technology and Typology, Log Cabin Bibliography

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU U.S. Government Documents (Utah Regional Forestry Depository) 1984 Log Cabin Studies: The Rocky Mountain Cabin, Log Cabin Technology and Typology, Log Cabin Bibliography United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/govdocs_forest Part of the Architectural Engineering Commons Recommended Citation United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, "Log Cabin Studies: The Rocky Mountain Cabin, Log Cabin Technology and Typology, Log Cabin Bibliography" (1984). Forestry. Paper 4. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/govdocs_forest/4 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Government Documents (Utah Regional Depository) at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Forestry by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 'EB \ L \ga~ United Siaies Department of Agriculture Foresl Serv ic e Intermountain Region • The Rocky Mountain Cabin Ogden, Utah Cull ural Resource • log Cabin Technology and Typology Re~ o rl No 9 LOG CABIN STUDIES By • log Cabin Bibliography Mary Wilson - The Rocky Mountain Cabi n - Log Ca bin Technology and Typology - Log Cabi n Bi b 1i ography CULTURAL RESOURCE REPORT NO. 9 USDA Forest Service Intennountain Region Ogden. Ut ' 19B4 .rr- THE ROCKY IOU NT AIN CA BIN By ' Ia ry l,i 1s on eDITORS NOTES The author is a cultural resource specialist for the Boise National Forest, Idaho . An earlier version of her Rocky Mountain Cabin study was submitted to the university of Idaho as an M.A. thesis . Cover photo : Homestead claim of Dr.