Edward East (1602–C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Harrison's Barometric Compensation Keeping It Simple

Harrison’s Barometric Compensation Keeping it Simple: A Description from Practice Jonathan Betts Introduction The last few years have seen considerable excitement, and some controversy, over the astonishingly successful trials of Burgess Clock B at the Observatory. In association with this work, there have been a number of published articles, including one last year in which we at the Observatory narrated the main facts surrounding the trials of Clock B [Ref.1: ‘A Second in 100 Days – The Result’ Rory McEvoy, Horological Journal, September 2015, pp 407-410]. Other published papers have provided theories as to how Harrison’s system might work, giving lots of historical context to those theories, [Ref: 2. ‘The Harrison Hill Test’, M.K.Hobden, HSN 2012-5 et Seq.; 3. ‘Dominion and Dynamic Stability’, M.K. Hobden, HSN 2015-4, pp 9-19; and 4. ‘Investigating the Harrison Pendulum Oscillator’, John Haine & Andrew Millington, HSN2016-3] and in this issue John Haine and Andrew Millington continue their commentary on Harrison’s pendulum oscillator and provide a theoretical model for how the barometric compensation system works. Adjusting a Harrison Clock As is now well known, adjusting a Harrison-type pendulum clock for optimum performance, including introducing compensation for barometric pressure changes, involves carrying out a series of what has been termed ‘hill tests’. In discussing this work among horologists, it is clear that many are of the opinion that the whole business is exceedingly complicated and time consuming. To quote one commentator, adjusting a Harrison clock appears to involve “overwhelming time and effort in fine-tuning”. -

![Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} My Time by Paul Harrison My Time [Harrison, Paul] on Amazon.Com](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0511/read-ebook-pdf-epub-my-time-by-paul-harrison-my-time-harrison-paul-on-amazon-com-1790511.webp)

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} My Time by Paul Harrison My Time [Harrison, Paul] on Amazon.Com

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} My Time by Paul Harrison My Time [Harrison, Paul] on Amazon.com. *FREE* shipping on qualifying offers. My Time Dec 20, 2012 · Paul Harrison tells the story of his year as World Champion, revealing the determination and willpower that is required to remain at the top of stock car racing. From the exhilaration of victory to the pressure of performing under the gold roof, My Time is a unique behind-the- scenes account of this brutal motorsport. Paul Harrison tells the story of his year as World Champion, revealing the determination and willpower that is required to remain at the top of stock car racing. From the exhilaration of victory to the pressure of performing under the gold roof, My Time is a unique behind-the-scenes account of this brutal motorsport. Nov 01, 2012 · My Time. “I just feel that my time has come.”. When Paul Harrison uttered those words before the Formula 1 Stock Car World Final in 2011, he was about to make history. It was the culmination of a life spent trying to match his father’s achievement and wear the gold roof that signifies the World Champion. Paul Harrison tells the story of his year as World Champion, revealing the determination … Thank you for your patience while we retrieve your images. Home | Photo Galleries | Recent | Guestbook | Profile | Contact My Time › Customer reviews ... This is a great diary of Paul Harrison's year as World Champion. It's great to get into the stock car driver's mind and see behind the scenes, it really makes you appreciate the work that goes on to go racing every weekend. -

The Illustrated Longitude

LONGITUDE The True Story of a Lone Genius Who Solved the Greatest Scientific Problem of His Time DAVA SOBEL Contents 1. Imaginary Lines 2. The Sea Before Time 3. Adrift in a Clockwork Universe 4. Time in a Bottle 5. Powder of Sympathy 6. The Prize 7. Cogmaker’s Journal 8. The Grasshopper Goes to Sea 9. Hands on Heaven’s Clock 10. The Diamond Timekeeper 11. Trial by Fire and Water 12. A Tale of Two Portraits 13. The Second Voyage of Captain James Cook 14. The Mass Production of Genius 15. In the Meridian Courtyard Acknowledgments Sources For my mother, Betty Gruber Sobel, a four-star navigator who can sail by the heavens but always drives by way of Canarsie. 1. Imaginary Lines When I’m playful I use the meridians of longitude and parallels of latitude for a seine, drag the Atlantic Ocean for whales. —MARK TWAIN, Life on the Mississippi Once on a Wednesday excursion when I was a little girl, my father bought me a beaded wire ball that I loved. At a touch, I could collapse the toy into a flat coil between my palms, or pop it open to make a hollow sphere. Rounded out, it resembled a tiny Earth, because its hinged wires traced the same pattern of intersecting circles that I had seen on the globe in my schoolroom— the thin black lines of latitude and longitude. The few colored beads slid along the wire paths haphazardly, like ships on the high seas. My father strode up Fifth Avenue to Rockefeller Center with me on his shoulders, and we stopped to stare at the statue of Atlas, carrying Heaven and Earth on his. -

Telling the Time in Norwich

Telling the time in Norwich Includes details of more than 50 viewable clocks and sundials Telling the time in Norwich Contents Introduction 1 Clockmaking in Norwich and Norfolk 3 The Gurney Clock 4 Clocks as memorials 5 Clocks as advertising 5 Ringing out the time 6 Clocks in the city landscape 6 The clocks directory 7 Sundials 24 Clocks and sundials shown on the maps 29 This project has been undertaken by the members of the Norwich Society Civic Environment Committee : Alan ‘Theo’ Theobald, John Trevelyan, Jonathan Hooton, Kate Nash, Michael Cross, Roy Holmes, Sue Pike and Sue Roe. Photographs are by committee members except where otherwise credited. The postcards are from the Norwich Society’s collection. The Society would like to thank Simon Michlmayr (S. Michlmayr & Co) and David Payne (British Sundial Society) for their time in discussing clocks and sundials, for the information they have imparted to us and for permission to use the photograph on page 2. David Payne’s Burlingham Sundial Trail can be accessed at https://sundialtrailsoftheburlinghamwalks.wordpress.com/ The Society has found the following publications and websites of use: • Norfolk and Norwich Clocks and Clockmakers (Clifford and Yvonne Bird, Phillimore 1996) • Norwich Knowledge (Michael Loveday, 2011) • The Medieval Churches of the City of Norwich (Nicholas Groves, Norwich HEART and East Publishing, 2010) • http://sundialsoc.org.uk/ [British Sundial Society] • https://greenwichmeantime.com/ • https://www.rmg.co.uk/discover/explore/greenwich-mean-time-gmt Introduction The Norwich Society’s Civic Environment Committee usually carries out an audit or survey each year. In 2017 we decided to look at public clocks and sundials. -

Simple Pendulum

The (Not So) Simple Pendulum ©2007-2008 Ron Doerfler Dead Reckonings: Lost Art in the Mathematical Sciences http://www.myreckonings.com/wordpress December 29, 2008 Pendulums are the defining feature of pendulum clocks, of course, but today they don’t elicit much thought. Most modern “pendulum” clocks simply drive the pendulum to provide a historical look, but a great deal of ingenuity originally went into their design in order to produce highly accurate clocks. This essay explores horologic design efforts that were so important at one time—not gearwork, winding mechanisms, crutches or escapements (which may appear as later essays), but the surprising inventiveness found in the “simple” pendulum itself. It is commonly known that Galileo (1564-1642) discovered that a swinging weight exhibits isochronism, purportedly by noticing that chandeliers in the Pisa cathedral had identical periods despite the amplitudes of their swings. The advantage here is that the driving force for the pendulum, which is difficult to regulate, could vary without affecting its period. Galileo was a medical student in Pisa at the time and began using it to check patients’ pulse rates. Galileo later established that the period of a pendulum varies as the square root of its length and is independent of the material of the pendulum bob (the mass at the end). One thing that surprised me when I encountered it is that the escapement preceded the pendulum—the verge escapement was used with hanging weights and possibly water clocks from at least the 14th century and probably much earlier. The pendulum provided a means of regulating such an escapement, and in fact Galileo invented the pin-wheel escapement to use in a pendulum clock he designed but never built. -

DAVA SOBEL Contents

LONGITUDE The True Story of a Lone Genius Who Solved the Greatest Scientific Problem of His Time DAVA SOBEL Contents 1. Imaginary Lines 2. The Sea Before Time 3. Adrift in a Clockwork Universe 4. Time in a Bottle 5. Powder of Sympathy 6. The Prize 7. Cogmaker’s Journal 8. The Grasshopper Goes to Sea 9. Hands on Heaven’s Clock 10. The Diamond Timekeeper 11. Trial by Fire and Water 12. A Tale of Two Portraits 13. The Second Voyage of Captain James Cook 14. The Mass Production of Genius 15. In the Meridian Courtyard Acknowledgments Sources For my mother, Betty Gruber Sobel, a four-star navigator who can sail by the heavens but always drives by way of Canarsie. 1. Imaginary Lines When I’m playful I use the meridians of longitude and parallels of latitude for a seine, drag the Atlantic Ocean for whales. —MARK TWAIN, Life on the Mississippi Once on a Wednesday excursion when I was a little girl, my father bought me a beaded wire ball that I loved. At a touch, I could collapse the toy into a flat coil between my palms, or pop it open to make a hollow sphere. Rounded out, it resembled a tiny Earth, because its hinged wires traced the same pattern of intersecting circles that I had seen on the globe in my schoolroom— the thin black lines of latitude and longitude. The few colored beads slid along the wire paths haphazardly, like ships on the high seas. My father strode up Fifth Avenue to Rockefeller Center with me on his shoulders, and we stopped to stare at the statue of Atlas, carrying Heaven and Earth on his. -

Time for Everyone the Origins, Evolution, and Future of Public Time

TIME FOR EVERYONE THE ORIGINS, EVOLUTION, AND FUTURE OF PUBLIC TIME 7–9 NoVEMBER 2013 CONTENTS The 2013 NAWCC Ward Francillon Time Symposium Symposium Organizers 2 Symposium Sponsors 3 Speakers William J. H. Andrewes 4 Chris Bailey 5 TIME FOR Jonathan Betts 6 Jed Z. Buchwald 7 EVERYONE Sean Carroll 8 THE ORIGINS, EVOLUTION, Geoff Chester 9 AND FUTURE OF PUBLIC TIME Jim Cipra 10 Tracy Dennison 11 David Eagleman 12 Mostyn Gale 13 E. C. Krupp 14 Program 15 Chris McKay 20 James Nye 21 Thomas O’Brian 22 William D. Phillips 23 A conference to explore the many facets of time from David Rooney 24 its origins in the natural cycles of astronomy through the history of how we found it, measured it, and now Lynn Rothschild 25 keep it today. Donald Saff 26 and Dava Sobel 27 John C. Taylor 28 MAJESTIC TIME Anthony Turner 29 A special exhibition to commemorate the 300th anniversary of the death of the eminent and ingenious Majestic Time Exhibition 30 clockmaker Thomas Tompion (1639–1713) Reception and Horological Information Exchange 32 7–9 November 2013 Map 33 California Institute of Technology and Hilton Pasadena Cover image: Detail of the dial of Big Ben Pasadena, California SYMPOSIUM ORGANIZERS SYMPOSIUM SPONSORS Executive Committee The kindness and generosity of the following individuals Mostyn Gale, Symposium Chairman and organizations have made this symposium possible Jim Cipra, Chairman, NAWCC Symposium Committee Founders William J. H. Andrewes Anonymous Private Donor Fundraising Publicity & Articles John C. Taylor William J. H. Andrewes Bob Frishman Sponsors Jim Cipra Bob McClelland David P. -

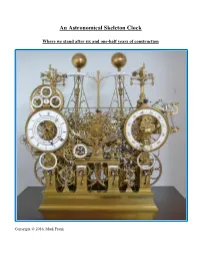

An Astronomical Skeleton Clock

An Astronomical Skeleton Clock Where we stand after six and one-half years of construction Copyright © 2016, Mark Frank Overview In August of 2007 the NAWCC Bulletin published the first article on a complex astronomical skeleton clock commissioned by the author and being built by Buchanan of Chelmsford, Australia.1 At that time a detailed full size wood mockup was completed and that article covered the proposed clock’s mechanical specifications and functions as depicted through the mockup. A follow up article was published in April 2011 marking roughly the halfway point in the construction. At that time the four movement trains with much of the ‘between the plates’ components were completed. These are the time, celestial, basic quarter and hour strike trains. As of July 2015 we are a decade on since the initial design and mockup and six and one-half years into construction. Right after the April 2011 Bulletin article there was a hiatus of two years during which time Buchanan had moved his shop to new quarters and taken on an intricate restoration project of another complex astronomical clock which was also the subject of a three part series in the Bulletin.2 Construction recommenced in the middle of 2013. I estimate completion sometime in 2018. In this third segment I will cover what has been accomplished since the 2011 Bulletin article. The entire left hand side of the dial complication work is complete as well as what is represented by the small dial below the large tellurian ring on the right, the strike selector, (Figure 1, prior page). -

JHA Feb 99.P65

JOURNAL FOR THE HISTORY OF ASTRONOMY VOLUME 30 EDITED BY M. A. HOSKIN SCIENCE HISTORY PUBLICATIONS LTD 1999 Editor: M. A. HOSKIN, Churchill College, Cambridge, England, CB3 0DS (phone: 01223-840284; fax: 01223-565532; e-mail: [email protected]) Associate Editor and Reviews Editor: OWEN GINGERICH, Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA Associate Editor: J. A. BENNETT (Oxford) Associate Editor of Archaeoastronomy Supplement: C. L. N. RUGGLES, School of Archaeological Studies, University of Leicester, Leicester, England, LEl 7RH Advisory Editors: DAVID H. DEVORKIN (National Air and Space Museum, Wash- ington), STEPHEN J. DICK (U.S. Naval Observatory), JERZY DOBRZYCKI (Polish Academy of Sciences), DOUGLAS C. HEGGIE (Edinburgh), DAVID A. KING (Frankfurt), JOHN LANKFORD (Kansas State), G. E. R. LLOYD (Cambridge), RAYMOND MERCIER, J. D. NORTH (Groningen), DAV I D PINGREE (Brown), C. L. N. RUGGLES (Leicester), F. RICHARD STEPHENSON (Durham), NOEL M. SWERDLOW (Chicago), ALBERT VAN HELDEN (Rice) Publisher: SCIENCE HISTORY PUBLICATIONS LTD, 16 Rutherford Road, Cambridge, England, CB2 2HH (phone: 01223-565532; fax: 01223-565532; e-mail: [email protected]; web site: http://members.aol.com/shpltd) Copyright: ©1999 by Science History Publications Ltd COPYING: This journal is registered with the Copyright Clearance Center, 21 Congress Street, Salem, Mass., 01970, USA. Permission to photocopy for internal or personal use or the internal or personal use of specific clients is granted by Science History Publications Ltd for libraries and users registered with C.C.C. subject to payment to C.C.C. of the per-copy fee indicated in the code on the first page of the article. -

Annual Review 2015–16

Royal Museums Greenwich Annual Review 2015–16 National Maritime Museum The Queen’s House Royal Observatory Greenwich Peter Harrison Planetarium Cutty Sark rmg.co.uk III t RMG Annual Review Title here Contents Subtitle here Introduction Royal Museums Greenwich [04] Chairman’s foreword [06] Director’s review [08] The Endeavour Project [10] Our year [12] Paragraph heading Text National Maritime Museum [20] Special exhibitions at NMM: 01. Against Captain’s Orders [22] Bringing the Special exhibitions at NMM: collections to life Samuel Pepys: Plague, Fire, Revolution [24] Royal Observatory Greenwich [26] Peter Harrison Planetarium [28] Cutty Sark [30] The Queen’s House [32] Acquisitions [36] Conservation [38] 02. Managing the collections [40] Caring for our Caird Library and Archive [42] collections Research [44] Marketing and digital outreach [48] Schools and formal learning [50] 03. [ ] Events and programming 54 Connecting with Media reviews [56] our audiences Volunteer programme [58] Funding Royal Museums Greenwich [62] 04. Membership [64] Development and fundraising [66] Making it Retail and commercial enterprises [68] happen Finance [71] Supporters of Royal Museums Greenwich 2015–16 [72] Royal Museums Greenwich 2015–16 [74] Image credits [74] Forthcoming exhibitions and openings [76] IV RMG Annual Review Introduction The Queen’s House Cutty Sark A beautiful royal villa, the Queen’s House was The world’s sole-surviving tea clipper is famous designed by Inigo Jones and completed around 1638 for her record-breaking passages around the for Charles I’s queen, Henrietta Maria. England’s first globe. Built in 1869 to carry tea back from China, truly classical building, the House features the elegant the ship has survived storms, mutiny and fire, Tulip Stairs and the breathtaking Great Hall. -

Articles Published in Antiquarian Horology Volumes 1-29 December 1953 - June 2008

Articles published in Antiquarian Horology Volumes 1-29 December 1953 - June 2008 VOLUME 1 1953 Vol.1/1 Roll of Founder members ............................................................................................................................................ 3 No Real Night by H Alan Lloyd ................................................................................................................................. 4 An Unorthodox Watch by C S Jagger........................................................................................................................ 6 The Tower of Babel by John W Castle ...................................................................................................................... 7 Vol.1/2 A neglected Chapter by T P Camerer Cuss .............................................................................................................. 10 A Viennese Flower-Vase Clock by Dr H von Bertele .............................................................................................. 13 Bejamin Lewis Vulliamy by S Benson Beevers ....................................................................................................... 15 15th & 16th Century Clocks by C B Drover................................................................................................................ 17 Early Oxford Clockmakers by Dr C F C Beeson ...................................................................................................... 19 Vol.1/3 The Huygens Collection by F A B Ward .................................................................................................................. -

1970S Brass Skeleton Clock ‘

1970s Brass Skeleton Clock ‘Concorde’, by Dent of London This clock was designed to commemorate the elegance and beauty of the Concorde supersonic aeroplane, brought into service in the same era. Fred Whitlock produced this model for Dent, based on a design by Martin Burgess and scaled to two thirds of its size. Initially, 25 were made. Then in c.2000 Whitlock made a further 10 from the parts he still had in stock. The clock has a mesmeric action; follow this link to our video. It utilizes a single pivot “grasshopper” escapement – designed by John Harrison in the 1720s – a system with negligible friction yet providing a near-continuous impulse. Less friction enables greater timekeeping accuracy. The massive compound pendulum has a leisurely two-second swing (four-second cycle). A pair of weights at the back are suspended on an endless chain pulley system, and these wind the spring remontoire to power the escapement. This spring is wound every 20 seconds. Every 7 minutes, when the large weight reaches its lowest point, it activates a switch which triggers a second remontoire, electrically rewinding the weight back to the top. The ingenious layout of this design allows for the winding of the escapement rementoire even when the weights are being wound. The plaque on the base states E. DENT & CO., LONDON, ENGLAND. NO JEWELS / NO. 005 (of 35), and bears Whitlock’s signature. The skeleton movement is protected by a brass-framed glass cover, which sits on the wooden base. A mains socket is required for the (two-meter long) power lead for the electrical Huygen’s-type rementoire, which can run on 110V or 240V.