Theosophy and Science

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Theosophy and the Origins of the Indian National Congress

THEOSOPHY AND THE ORIGINS OF THE INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS By Mark Bevir Department of Political Science University of California, Berkeley Berkeley CA 94720 USA [E-mail: [email protected]] ABSTRACT A study of the role of theosophy in the formation of the Indian National Congress enhances our understanding of the relationship between neo-Hinduism and political nationalism. Theosophy, and neo-Hinduism more generally, provided western-educated Hindus with a discourse within which to develop their political aspirations in a way that met western notions of legitimacy. It gave them confidence in themselves, experience of organisation, and clear intellectual commitments, and it brought them together with liberal Britons within an all-India framework. It provided the background against which A. O. Hume worked with younger nationalists to found the Congress. KEYWORDS: Blavatsky, Hinduism, A. O. Hume, India, nationalism, theosophy. 2 REFERENCES CITED Archives of the Theosophical Society, Theosophical Society, Adyar, Madras. Banerjea, Surendranath. 1925. A Nation in the Making: Being the Reminiscences of Fifty Years of Public Life . London: H. Milford. Bharati, A. 1970. "The Hindu Renaissance and Its Apologetic Patterns". In Journal of Asian Studies 29: 267-88. Blavatsky, H.P. 1888. The Secret Doctrine: The Synthesis of Science, Religion and Philosophy . 2 Vols. London: Theosophical Publishing House. ------ 1972. Isis Unveiled: A Master-Key to the Mysteries of Ancient and Modern Science and Theology . 2 Vols. Wheaton, Ill.: Theosophical Publishing House. ------ 1977. Collected Writings . 11 Vols. Ed. by Boris de Zirkoff. Wheaton, Ill.: Theosophical Publishing House. Campbell, B. 1980. Ancient Wisdom Revived: A History of the Theosophical Movement . Berkeley: University of California Press. -

Echoes of the Orient: the Writings of William Quan Judge

ECHOES ORIENTof the VOLUME I The Writings of William Quan Judge Echoes are heard in every age of and their fellow creatures — man and a timeless path that leads to divine beast — out of the thoughtless jog trot wisdom and to knowledge of our pur- of selfish everyday life.” To this end pose in the universal design. Today’s and until he died, Judge wrote about resurgent awareness of our physical the Way spoken of by the sages of old, and spiritual inter dependence on this its signposts and pitfalls, and its rel- grand evolutionary journey affirms evance to the practical affairs of daily those pioneering keynotes set forth in life. HPB called his journal “pure Bud- the writings of H. P. Blavatsky. Her dhi” (awakened insight). task was to re-present the broad This first volume of Echoes of the panorama of the “anciently universal Orient comprises about 170 articles Wisdom-Religion,” to show its under- from The Path magazine, chronologi- lying expression in the world’s myths, cally arranged and supplemented by legends, and spiritual traditions, and his popular “Occult Tales.” A glance to show its scientific basis — with at the contents pages will show the the overarching goal of furthering the wide range of subjects covered. Also cause of universal brotherhood. included are a well-documented 50- Some people, however, have page biography, numerous illustra- found her books diffi cult and ask for tions, photographs, and facsimiles, as something simpler. In the writings of well as a bibliography and index. William Q. Judge, one of the Theosophical Society’s co-founders with HPB and a close personal colleague, many have found a certain William Quan Judge (1851-1896) was human element which, though not born in Dublin, Ireland, and emigrated lacking in HPB’s works, is here more with his family to America in 1864. -

Theosophy and the Arts

Theosophy and the Arts Ralph Herman Abraham January 17, 2017 Abstract The cosmology of Ancient India, as transcribed by the Theosophists, con- tains innovations that greatly influenced modern Western culture. Here we bring these novel embellishments to the foreground, and explain their influ- ence on the arts. 1. Introduction Following the death of Madame Blavatsky in 1891, Annie Besant ascended to the leadership of the Theosophical Society. The literature of the post-Blavatsky period began with the very influential Thought-Forms by Besant and C. W. Leadbeater, of 1901. The cosmological model of Theosophy is similar to the classical Sanskrit of 6th century BCE. The pancha kosa, in particular, is the model for these authors. The classical pancha kosa (five sheaths or levels) are, from bottom up: physical, vital, mental, intellectual, and bliss. The related idea of the akashic record was promoted by Alfred Sinnett in his book Esoteric Buddhism of 1884. 2. The Esoteric Planes and Bodies The Sanskrit model was adapted and embellished by the early theosophists. 2-1. Sinnett Alfred Percy Sinnett (1840 { 1921) moved to India in 1879, where he was the editor of an English daily. Sinnett returned to England in 1884, where his book, Esoteric 1 Buddhism, was published that year. This was the first text on Theosophy, and was based on his correspondence with masters in India. 2-2. Blavatsky Helena Petrovna Blavatsky (1831 { 1891) { also known as HPB { was a Russian occultist and world traveller, While reputedly in India in the 1850s, she came under the influence of the ancient teachings of Hindu and Buddhist masters. -

The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon the Theosophical Seal a Study for the Student and Non-Student

The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon The Theosophical Seal A Study for the Student and Non-Student by Arthur M. Coon This book is dedicated to all searchers for wisdom Published in the 1800's Page 1 The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon INTRODUCTION PREFACE BOOK -1- A DIVINE LANGUAGE ALPHA AND OMEGA UNITY BECOMES DUALITY THREE: THE SACRED NUMBER THE SQUARE AND THE NUMBER FOUR THE CROSS BOOK 2-THE TAU THE PHILOSOPHIC CROSS THE MYSTIC CROSS VICTORY THE PATH BOOK -3- THE SWASTIKA ANTIQUITY THE WHIRLING CROSS CREATIVE FIRE BOOK -4- THE SERPENT MYTH AND SACRED SCRIPTURE SYMBOL OF EVIL SATAN, LUCIFER AND THE DEVIL SYMBOL OF THE DIVINE HEALER SYMBOL OF WISDOM THE SERPENT SWALLOWING ITS TAIL BOOK 5 - THE INTERLACED TRIANGLES THE PATTERN THE NUMBER THREE THE MYSTERY OF THE TRIANGLE THE HINDU TRIMURTI Page 2 The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon THE THREEFOLD UNIVERSE THE HOLY TRINITY THE WORK OF THE TRINITY THE DIVINE IMAGE " AS ABOVE, SO BELOW " KING SOLOMON'S SEAL SIXES AND SEVENS BOOK 6 - THE SACRED WORD THE SACRED WORD ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Page 3 The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon INTRODUCTION I am happy to introduce this present volume, the contents of which originally appeared as a series of articles in The American Theosophist magazine. Mr. Arthur Coon's careful analysis of the Theosophical Seal is highly recommend to the many readers who will find here a rich store of information concerning the meaning of the various components of the seal Symbology is one of the ancient keys unlocking the mysteries of man and Nature. -

Morya, One of the "Masters of the Ancient Wisdom" Spoken of in Modern Theosophy and in the Ascended Master Teachings I

Morya, one of the "Masters of the Ancient Wisdom" spoken of in modern Theosophy and in the Ascended Master Teachings is considered one of the "Ascended Masters." He is also known as the "Chohan of the First Ray". Morya first became known to the modern world when H. P. Blavatsky declared that he and Kkuthumi were her guides in establishing the Theosophical Society. Seven Rays Blavatsky wrote that Masters Morya and Koot Hoomi belonged to a group of highly developed humans known as the Great White Brotherhood. Although Master Morya's personality has been depicted in some detail by various theosophical authors, critics point out that there is little evidence that Blavatsky's Masters, including Morya, ever existed. There being a dearth of material evidence to prove anything with certainty, this article focuses on presenting the narratives about Morya given by various believers in his existence, beginning from the time of his alleged contacts with 19th-century theosophists. Morya Khan is known in many New Age religions as the Ascended Master of the Blue Ray or First Ray. He is well known as the 'Master M' who worked with the Kuthumi in the late nineteenth century to establish the Theosophical Society and to spread the knowledge of higher truths to a wider circle among mankind. After his alleged ascension in the late 1800s, he continued working for this same purpose. He is believed to have ascended in 1898. http://www.crystalinks.com/morya.html אל מוריה الموريا Ελ Μόρυα 天使のエル·モリヤ http://blogs.yahoo.co.jp/chain_of_flowers723/56856858.html Morya (Theosophy) For other uses, see Morya. -

Theosophy Intro.Pdf

THEOSOPHY AN INTRODUCTORY STUDY COURSE FOURTH EDITION by John Algeo Department of Education THE THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY IN AMERICA P. O. Box 270, Wheaton, IL 60189-0270 Copyright © 1996, 2003, 2007 by the Theosophical Society in America Based on the Introductory Study Course in Theosophy by Emogene S. Simons, copyright © 1935, 1938 by the Theosophical Society in America, revised by Virginia Hanson, copyright © 1967, 1969 by the Theosophical Society in America. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without written permission except for quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. THE THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY IN AMERICA For additional information, contact: Department of Information The Theosophical Society in America P. O. Box 270 Wheaton, IL 60189-0270 E-mail: [email protected] Web : www.theosophical.org 2 CONTENTS Introduction 4 1. What Is Theosophy? 7 2. The Ancient Wisdom in the Modern World 17 3. Universal Brotherhood 23 4. Human Beings and Our Bodies 30 5. Life after Death 38 6. Reincarnation 45 7. Karma 56 8. The Power of Thought 64 9. The Question of Evil 70 10. The Plan and Purpose of Life 77 11. The Rise and Fall of Civilizations 92 12. The Ancient Wisdom in Daily Life 99 Bibliography 104 FIGURES 1. The Human Constitution 29 2. Reincarnation 44 3. Evolution of the Soul 76 4. The Three Life Waves 81 5. The Seven Rays 91 6. The Lute of the Seven Planes 98 3 INTRODUCTION WE LIVE IN AN AGE OF AFFLUENCE and physical comfort. We drive bulky SUVs, talk incessantly over our cell phones, amuse ourselves with DVDs, eat at restaurants more often than at home, and expect all the amenities of life as our birthright. -

The Theosophist

THE THEOSOPHIST VOL. 131 NO. 1 OCTOBER 2009 CONTENTS On the Watch-Tower 3 Radha Burnier Theosophy for a New Generation of Inquirers 7 Colin Price An Emerging World View 12 Shirley J. Nicholson What is Theosophy? 15 H. P. Blavatsky Theosophy for a New Generation of Enquirers 23 Surendra Narayan The Eternal Values of the Divine Wisdom 28 Bhupendra R. Vora The Theosophist: Past is Prologue 32 John Algeo Fragments of the Ageless Wisdom 37 The Theosophical Society for a New Generation of Enquirers 38 Dara Tatray Back to Blavatsky will Fossilize Theosophy Forwards with Blavatsky will Vitalize Theosophy 43 Edi D. Bilimoria Statement by Members Assembled in Brasilia, July 2009 51 International Directory 54 Editor: Mrs Radha Burnier NOTE: Articles for publication in The Theosophist should be sent to the Editorial Office. Cover: H. P. Blavatsky. Montage including cover of The Theosophist, 1882 Adyar Archives Official organ of the President, founded by H. P. Blavatsky, 1879. The Theosophical Society is responsible only for official notices appearing in this magazine. THE THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY Founded 17 November 1875 President: Mrs Radha Burnier Vice-President: Mrs Linda Oliveira Secretary: Mrs Kusum Satapathy Treasurer: Miss Keshwar Dastur Headquarters: ADYAR, CHENNAI (MADRAS) 600 020, INDIA Emails: Below Secretary: [email protected] Treasury: [email protected] Fax: (+91-44) 2446-3464 Adyar Library and Research Centre: [email protected] Theosophical Publishing House: [email protected] & [email protected] Fax: (+91-44) 2490-1399 Editorial Office: [email protected] Website: http://www.ts-adyar.org The Theosophical Society is composed of students, belonging to any religion in the world or to none, who are united by their approval of the Societys Objects, by their wish to remove religious antagonisms and to draw together men of goodwill, whatsoever their religious opinions, and by their desire to study religious truths and to share the results of their studies with others. -

De Zirkoff on the Dream That Never Dies V

Boris de Zirkoff The dream that never dies! De Zirkoff on the dream that never dies v. 19.10, www.philaletheians.co.uk, 17 February 2019 Page 1 of 5 THEOSOPHY AND THEOSOPHISTS SERIES THE DREAM THAT NEVER DIES A united mankind, a rebirth of esoteric wisdom, a world at peace. “The Dream That Never Dies!” was spoken by Boris Mikhailovich de Zirkoff (1902-1981) at the Cen- tenary World Congress of the Theosophical Society, New York, November 17th, 1975; it was first pub- lished in The Theosophist, January 1976, and subsequently included in W. Emmett Small. (Comp. & Ed.) The Dream That Never Dies: Boris de Zirkoff speaks out on Theosophy. San Diego: Point Loma Publications, Inc., 1983 — a compilation of fifty articles from the independent Theosophical Journal Theosophia, edited by de Zirkoff from its inception, in May 1944, until his death on the 4th March, 1981; pp. 30-33. Frontispiece by Richard Hoedl. LL OF US HERE, ASSEMBLED IN THIS HALL in ties of brotherhood, are a par- tial embodiment of a noble dream — a dream of ancient days, a dream living A in the hearts of men from ages past, a dream implanted in man’s mind by his original Guides and divine Instructors — the dream of a united mankind, of a rebirth of esoteric wisdom, and of a world at peace! From immemorial past, as far as tradition can tell, the noblest men and women of all times have dreamt that dream. From time to time, movements have arisen to bring about the realization of that dream, at least on some small scale. -

8. May-June 09 AQUARIAN THEOSOPHIST SUPPLEMENT V2

TThhee AAqquuaarriiaann TThheeoossoopphhiisstt SUPPLEMENT Volume IX # 8, June 17 (incl. May 17) 2009 Blog http://aquariantheosophist.wordpress.com Free by email from the Editors : [email protected] Archive: http://www.teosofia.com/AT.html OLD DIARY LEAVES – FULL VERSION “““OLD“OLD DIARY LEAVESLEAVES” ””” (FULL VERSION OF THE PLAY) A play in 4 Acts by Alan Hughes The formation of the Theosophical Society lasting about 50 minutes A NOTE ABOUT THE PLAY Dramatis Personae in order of appearance I spoke to Alan Hughes about this play just Narr. – the Narrator, and melodramatic “deus after its world premiere (!!?). He has extracted ex machina” for this play. and dramatised this story from “Old Diary HPB – Helena Petrovna Blavatsky – A Russian Leaves” by HS Olcott, which is one of the main noblewoman, domineering, perhaps historical sources about the foundation of the speaking English with a French accent. Society. HSO – Henry Steele Olcott – A lawyer and Colonel from the American Civil War. Alan chose a simple 4 act structure featuring:- WQJ – William Quan Judge – An Irish lawyer. Honto – an American Indian squaw – a first an introduction of the 3 main materialised spirit. characters, Felt – George Felt – an architect and engineer, then the first main meeting between HPB who gave the first talk “The Lost Canon and HSO, of Proportion of the Egyptians". Other materialised spirits may also appear, as then the talk by G Felt which was the first required. time the formation of a society was mentioned, The Audience – ideally of a melodramatic disposition and willing to join in! then, finally, the last scene before the departure of HPB and HSO to Europe and then India. -

Dreamworld Tibet: Western Illusions

Dreamworld Tibet: Western Illusions Martin Brauen (Trumbull, CT, USA: Weatherhill, 2004) First published as Traumwelt Tibet: Westliche Trugbilder (Berne: Verlag Paul Haupt, 2000) Part 2 In Search of 'Shambha-la' and the Aryan Lamas: The Tibet images of the theosophists, occultists, Nazis and neo-Nazis A. The Theosophists and some of their followers pp. 24-37 (excerpt; illustrations left out; pagination in square brackets; footnotes and relevant bibliography at end of document) === [24] An Aryan brotherhood For centuries we have had in Thibet a moral, pure hearted, simple people, unblest with civilization, hence—untainted by its vices. For ages has been Thibet the last corner of the globe not so entirely corrupted as to preclude the mingling together of the two atmospheres—the physical and the spiritual. 1 These lines were ascribed to Koot Hoomi, who was said to have belonged to a secret brotherhood in Tibet. Like other supposed 'brothers' in Tibet, he was most closely linked with Helena Petrovna Blavatsky (1831-1891), the founder of Theosophy. The first meeting of HPB (we shall frequently use this abbreviation for Helena Petrovna Blavatsky below) with her 'Master' goes back to the year 1851, but as so often in Blavatsky's biography, there exist various accounts, sometimes contradictory, of this first meeting. Her Master, [Illustration: Drawing of Master Koot Hoomi Lal Singh] 17 . Master Koot Hoomi Lal Singh, who was said to have been Pythagoras in a previous incarnation and to have lived in Shigatse during Helena Blavatsky 's lifetime. Many of the mysterious letters that Helena Blavatsky and other Theosophists received by miraculous means are supposed to originate from him. -

The Library of Rudolf Steiner: the Books in English Paull, John

www.ssoar.info The Library of Rudolf Steiner: The Books in English Paull, John Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Paull, J. (2018). The Library of Rudolf Steiner: The Books in English. Journal of Social and Development Sciences, 9(3), 21-46. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-59648-1 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY Lizenz (Namensnennung) zur This document is made available under a CC BY Licence Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden (Attribution). For more Information see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.de Journal of Social and Development Sciences (ISSN 2221-1152) Vol. 9, No. 3, pp. 21-46, September 2018 The Library of Rudolf Steiner: The Books in English John Paull School of Technology, Environments and Design, University of Tasmania, Hobart, Australia [email protected], [email protected] Abstract: The New Age philosopher, Rudolf Steiner (1861-1925), was the most prolific and arguably the most influential philosopher of his era. He assembled a substantial library, of approximately 9,000 items, which has been preserved intact since his death. Most of Rudolf Steiner’s books are in German, his native language however there are books in other languages, including English, French, Italian, Swedish, Sanskrit and Latin. There are more books in English than in any other foreign language. Steiner esteemed English as “a universal world language”. The present paper identifies 327 books in English in Rudolf Steiner’s personal library. -

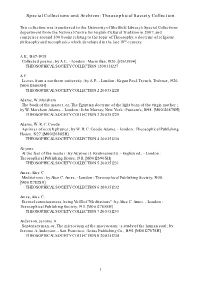

Theosophical Society Collection.Doc

Special Collections and Archives: Theosophical Society Collection This collection was transferred to the University of Sheffield Library’s Special Collections department from the National Centre for English Cultural Tradition in 2007, and comprises around 500 books relating to the topic of Theosophy, a doctrine of religious philosophy and metaphysics which developed in the late 19th century. A. E., 1867-1935 Collected poems ; by A. E.. - London : Macmillan, 1920. [v2613994] THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY COLLECTION 1 200351227 A. F. Leaves from a northern university ; by A. F.. - London : Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner, 1926. [M0012686SH] THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY COLLECTION 2 200351228 Adams, W. Marsham The book of the master, or, The Egyptian doctrine of the light born of the virgin mother ; by W. Marsham Adams. - London : John Murray; New York : Putnam's, 1898. [M0012687SH] THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY COLLECTION 3 200351229 Adams, W. R. C. Coode A primer of occult physics ; by W. R. C. Coode Adams. - London : Theosophical Publishing House, 1927. [M0012688SH] THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY COLLECTION 4 200351230 Alcyone At the feet of the master ; by Alcyone (J. Krishnamurti). - English ed.. - London : Theosophical Publishing House, 1911. [M0012690SH] THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY COLLECTION 5 200351231 Ames, Alice C. Meditations ; by Alice C. Ames. - London : Theosophical Publishing Society, 1908. [M0012782SH] THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY COLLECTION 6 200351232 Ames, Alice C. Eternal consciousness, being Vol.II of "Meditations" ; by Alice C. Ames. - London : Theosophical Publishing