John R. Searle's Chinese Room Argument

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Artificial Intelligence Is Stupid and Causal Reasoning Won't Fix It

Artificial Intelligence is stupid and causal reasoning wont fix it J. Mark Bishop1 1 TCIDA, Goldsmiths, University of London, London, UK Email: [email protected] Abstract Artificial Neural Networks have reached `Grandmaster' and even `super- human' performance' across a variety of games, from those involving perfect- information, such as Go [Silver et al., 2016]; to those involving imperfect- information, such as `Starcraft' [Vinyals et al., 2019]. Such technological developments from AI-labs have ushered concomitant applications across the world of business, where an `AI' brand-tag is fast becoming ubiquitous. A corollary of such widespread commercial deployment is that when AI gets things wrong - an autonomous vehicle crashes; a chatbot exhibits `racist' behaviour; automated credit-scoring processes `discriminate' on gender etc. - there are often significant financial, legal and brand consequences, and the incident becomes major news. As Judea Pearl sees it, the underlying reason for such mistakes is that \... all the impressive achievements of deep learning amount to just curve fitting". The key, Pearl suggests [Pearl and Mackenzie, 2018], is to replace `reasoning by association' with `causal reasoning' - the ability to infer causes from observed phenomena. It is a point that was echoed by Gary Marcus and Ernest Davis in a recent piece for the New York Times: \we need to stop building computer systems that merely get better and better at detecting statistical patterns in data sets { often using an approach known as \Deep Learning" { and start building computer systems that from the moment of arXiv:2008.07371v1 [cs.CY] 20 Jul 2020 their assembly innately grasp three basic concepts: time, space and causal- ity"[Marcus and Davis, 2019]. -

The Thought Experiments Are Rigged: Mechanistic Understanding Inhibits Mentalistic Understanding

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Philosophy Theses Department of Philosophy Summer 8-13-2013 The Thought Experiments are Rigged: Mechanistic Understanding Inhibits Mentalistic Understanding Toni S. Adleberg Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/philosophy_theses Recommended Citation Adleberg, Toni S., "The Thought Experiments are Rigged: Mechanistic Understanding Inhibits Mentalistic Understanding." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2013. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/philosophy_theses/141 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Philosophy at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE THOUGHT EXPERIMENTS ARE RIGGED: MECHANISTIC UNDERSTANDING INHIBITS MENTALISTIC UNDERSTANDING by TONI ADLEBERG Under the Direction of Eddy Nahmias ABSTRACT Many well-known arguments in the philosophy of mind use thought experiments to elicit intuitions about consciousness. Often, these thought experiments include mechanistic explana- tions of a systems’ behavior. I argue that when we understand a system as a mechanism, we are not likely to understand it as an agent. According to Arico, Fiala, Goldberg, and Nichols’ (2011) AGENCY Model, understanding a system as an agent is necessary for generating the intuition that it is conscious. Thus, if we are presented with a mechanistic description of a system, we will be very unlikely to understand that system as conscious. Many of the thought experiments in the philosophy of mind describe systems mechanistically. I argue that my account of consciousness attributions is preferable to the “Simplicity Intuition” account proposed by David Barnett (2008) because it is more explanatory and more consistent with our intuitions. -

Introduction to Philosophy Fall 2019—Test 3 1. According to Descartes, … A. What I Really Am Is a Body, but I Also Possess

Introduction to Philosophy Fall 2019—Test 3 1. According to Descartes, … a. what I really am is a body, but I also possess a mind. b. minds and bodies can’t causally interact with one another, but God fools us into believing they do. c. cats and dogs have immortal souls, just like us. d. conscious states always have physical causes, but never have physical effects. e. what I really am is a mind, but I also possess a body. 2. Which of the following would Descartes agree with? a. We can conceive of existing without a body. b. We can conceive of existing without a mind. c. We can conceive of existing without either a mind or a body. d. We can’t conceive of mental substance. e. We can’t conceive of material substance. 3. Substance dualism is the view that … a. there are two kinds of minds. b. there are two kinds of “basic stuff” in the world. c. there are two kinds of physical particles. d. there are two kinds of people in the world—those who divide the world into two kinds of people, and those that don’t. e. material substance comes in two forms, matter and energy. 4. We call a property “accidental” (as opposed to “essential”) when ... a. it is the result of a car crash. b. it follows from a thing’s very nature. c. it is a property a thing can’t lose (without ceasing to exist). d. it is a property a thing can lose (without ceasing to exist). -

Preston, John, & Bishop, Mark

Preston, John, & Bishop, Mark (2002), Views into the Chinese Room: New Essays on Searle and Artificial Intelligence (Oxford: Oxford University Press), xvi + 410 pp., ISBN 0-19-825057-6. Reviewed by: William J. Rapaport Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Department of Philosophy, and Center for Cognitive Science, State University of New York at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY 14260-2000; [email protected], http://www.cse.buffalo.edu/ rapaport ∼ This anthology’s 20 new articles and bibliography attest to continued interest in Searle’s (1980) Chinese Room Argument. Preston’s excellent “Introduction” ties the history and nature of cognitive science, computation, AI, and the CRA to relevant chapters. Searle (“Twenty-One Years in the Chinese Room”) says, “purely . syntactical processes of the implemented computer program could not by themselves . guarantee . semantic content . essential to human cognition” (51). “Semantic content” appears to be mind-external entities “attached” (53) to the program’s symbols. But the program’s implementation must accept these entities as input (suitably transduced), so the program in execution, accepting and processing this input, would provide the required content. The transduced input would then be internal representatives of the external content and would be related to the symbols of the formal, syntactic program in ways that play the same roles as the “attachment” relationships between the external contents and the symbols (Rapaport 2000). The “semantic content” could then just be those mind-internal -

Digital Culture: Pragmatic and Philosophical Challenges

DIOGENES Diogenes 211: 23–39 ISSN 0392-1921 Digital Culture: Pragmatic and Philosophical Challenges Marcelo Dascal Over the coming decades, the so-called telematic technologies are destined to grow more and more encompassing in scale and the repercussions they will have on our professional and personal lives will become ever more accentuated. The transforma- tions resulting from the digitization of data have already profoundly modified a great many of the activities of human life and exercise significant influence on the way we design, draw up, store and send documents, as well as on the means used for locating information in libraries, databases and on the net. These changes are transforming the nature of international communication and are modifying the way in which we carry out research, engage in study, keep our accounts, plan our travel, do our shopping, look after our health, organize our leisure time, undertake wars and so on. The time is not far off when miniaturized digital systems will be installed everywhere – in our homes and offices, in the car, in our pockets or even embedded within the bodies of each one of us. They will help us to keep control over every aspect of our lives and will efficiently and effectively carry out multiple tasks which today we have to devote precious time to. As a consequence, our ways of acting and thinking will be transformed. These new winds of change, which are blowing strongly, are giving birth to a new culture to which the name ‘digital culture’ has been given.1 It is timely that a study should be made of the different aspects and consequences of this culture, but that this study should not be just undertaken from the point of view of the simple user who quickly embraces the latest successful inno- vation, in reaction essentially to market forces. -

Zombie Mouse in a Chinese Room

Philosophy and Technology manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) Zombie mouse in a Chinese room Slawomir J. Nasuto · J. Mark Bishop · Etienne B. Roesch · Matthew C. Spencer the date of receipt and acceptance should be inserted later Abstract John Searle's Chinese Room Argument (CRA) purports to demon- strate that syntax is not sucient for semantics, and hence that because com- putation cannot yield understanding, the computational theory of mind, which equates the mind to an information processing system based on formal com- putations, fails. In this paper, we use the CRA, and the debate that emerged from it, to develop a philosophical critique of recent advances in robotics and neuroscience. We describe results from a body of work that contributes to blurring the divide between biological and articial systems: so-called ani- mats, autonomous robots that are controlled by biological neural tissue, and what may be described as remote-controlled rodents, living animals endowed with augmented abilities provided by external controllers. We argue that, even though at rst sight these chimeric systems may seem to escape the CRA, on closer analysis they do not. We conclude by discussing the role of the body- brain dynamics in the processes that give rise to genuine understanding of the world, in line with recent proposals from enactive cognitive science1. Slawomir J. Nasuto Univ. Reading, Reading, UK, E-mail: [email protected] J. Mark Bishop Goldsmiths, Univ. London, UK, E-mail: [email protected] Etienne B. Roesch Univ. Reading, Reading, UK, E-mail: [email protected] Matthew C. -

A Logical Hole in the Chinese Room

Minds & Machines (2009) 19:229–235 DOI 10.1007/s11023-009-9151-9 A Logical Hole in the Chinese Room Michael John Shaffer Received: 27 August 2007 / Accepted: 18 May 2009 / Published online: 12 June 2009 Ó Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2009 Abstract Searle’s Chinese Room Argument (CRA) has been the object of great interest in the philosophy of mind, artificial intelligence and cognitive science since its initial presentation in ‘Minds, Brains and Programs’ in 1980. It is by no means an overstatement to assert that it has been a main focus of attention for philosophers and computer scientists of many stripes. It is then especially interesting to note that relatively little has been said about the detailed logic of the argument, whatever significance Searle intended CRA to have. The problem with the CRA is that it involves a very strong modal claim, the truth of which is both unproved and highly questionable. So it will be argued here that the CRA does not prove what it was intended to prove. Keywords Chinese room Á Computation Á Mind Á Artificial intelligence Searle’s Chinese Room Argument (CRA) has been the object of great interest in the philosophy of mind, artificial intelligence and cognitive science since its initial presentation in ‘Minds, Brains and Programs’ in 1980. It is by no means an overstatement to assert that it has been a main focus of attention for philosophers and computer scientists of many stripes. In fact, one recent book (Preston and Bishop 2002) is exclusively dedicated to the ongoing debate about that argument 20 some years since its introduction. -

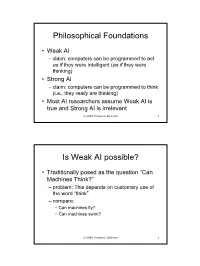

Philosophical Foundations Is Weak AI Possible?

Philosophical Foundations • Weak AI – claim: computers can be programmed to act as if they were intelligent (as if they were thinking) • Strong AI – claim: computers can be programmed to think (i.e., they really are thinking) • Most AI researchers assume Weak AI is true and Strong AI is irrelevant (c) 2003 Thomas G. Dietterich 1 Is Weak AI possible? • Traditionally posed as the question “Can Machines Think?” – problem: This depends on customary use of the word “think” – compare: • Can machines fly? • Can machines swim? (c) 2003 Thomas G. Dietterich 2 1 Flying and Swimming • In English, machines can fly but they do not swim • In Russian, machines can do both (c) 2003 Thomas G. Dietterich 3 Arguments against Weak AI • Turing’s famous paper “Computing Machinery and Intelligence” (1950) – Argument from disability – Argument from mathematics – Argument from informality (c) 2003 Thomas G. Dietterich 4 2 Argument from Disability • A machine will never be able to… – be kind, resourceful, beautiful, friendly, have initiative, have a sense of humor, tell right from wrong, make mistakes, fall in love, enjoy strawberries and cream, make someone fall in love with it, learn from experience, use words properly, be the subject of its own thought, have as much diversity of behavior as man, do something really new. • But nowadays, computers do many things that used to be exclusively human: – play chess, checkers, and other games, inspect parts on assembly lines, check the spelling of documents, steer cars and helicopters, diagnose diseases, and 100’s of other things. Computers have made small but significant discoveries in astronomy, mathematics, chemistry, minerology, biology, computer science, and other fields (c) 2003 Thomas G. -

Dancing with Pixies: Strong Artificial Intelligence and Panpsychism Mark

(6694 words) Dancing with Pixies: Strong Artificial Intelligence and Panpsychism Mark Bishop In 1994 John Searle stated (Searle 1994, pp.11-12) that the Chinese Room Argument (CRA) is an attempt to prove the truth of the premise: 1: Syntax is not sufficient for semantics which, together with the following: 2: Programs are formal, 3: Minds have content led him to the conclusion that ‘programs are not minds’ and hence that computationalism, the idea that the essence of thinking lies in computational processes and that such processes thereby underlie and explain conscious thinking, is false. The argument presented in this paper is not a direct attack or defence of the CRA, but relates to the premise at its heart, that syntax is not sufficient for semantics, via the closely associated propositions that semantics is not intrinsic to syntax and that syntax is not intrinsic to physics.1 However, in contrast to the CRA’s critique of the link between syntax and semantics, this 1 See Searle (1990, 1992) for related discussion. 1 paper will explore the associated link between syntax and physics. The main argument presented here is not significantly original – it is a simple reflection upon that originally given by Hilary Putnam (Putnam 1988) and criticised by David Chalmers and others.2 In what follows, instead of seeking to justify Putnam’s claim that, “every open system implements every Finite State Automaton (FSA)”, and hence that psychological states of the brain cannot be functional states of a computer, I will seek to establish the weaker result that, over a finite time window every open system implements the trace of a particular FSA Q, as it executes program (p) on input (x). -

The Chinese Room: Just Say “No!” to Appear in the Proceedings of the 22Nd Annual Cognitive Science Society Conference, (2000), NJ: LEA

The Chinese Room: Just Say “No!” To appear in the Proceedings of the 22nd Annual Cognitive Science Society Conference, (2000), NJ: LEA Robert M. French Quantitative Psychology and Cognitive Science University of Liège 4000 Liège, Belgium email: [email protected] Abstract presenting Searle’s well-known transformation of the It is time to view John Searle’s Chinese Room thought Turing’s Test. Unlike other critics of the Chinese Room experiment in a new light. The main focus of attention argument, however, I will not take issue with Searle’s has always been on showing what is wrong (or right) argument per se. Rather, I will focus on the argument’s with the argument, with the tacit assumption being that central premise and will argue that the correct approach somehow there could be such a Room. In this article I to the whole argument is simply to refuse to go beyond argue that the debate should not focus on the question “If this premise, for it is, as I hope to show, untenable. a person in the Room answered all the questions in perfect Chinese, while not understanding a word of Chinese, what would the implications of this be for The Chinese Room strong AI?” Rather, the question should be, “Does the Instead of Turing’s Imitation Game in which a very idea of such a Room and a person in the Room who computer in one room and a person in a separate room is able to answer questions in perfect Chinese while not both attempt to convince an interrogator that they are understanding any Chinese make any sense at all?” And I believe that the answer, in parallel with recent human, Searle asks us to begin by imagining a closed arguments that claim that it would be impossible for a room in which there is an English-speaker who knows machine to pass the Turing Test unless it had no Chinese whatsoever. -

Quantum Theory, the Chinese Room Argument and the Symbol Grounding Problem Abstract

Quantum Theory, the Chinese Room Argument and the * Symbol Grounding Problem Ravi Gomatam † [email protected] Abstract: I o ffer an alternative to Searle’s original Chinese Room argument which I call the Sanskrit Room argument (SRA). SRA distinguishes between syntactic TOKEN and semantic SYMBOL manipulations and shows that both are involved in human language understanding. Within classical mechanics, which gives an adequate scientific account of TOKEN manipulation, a symbol remains a subjective construct. I describe how an objective, quantitative theory of semantic symbols could be developed by applying the Schrodinger equation directly to macroscopic objects independent of Born’s rule and hence independent of current statistical quantum mechanics. Such a macroscopic quantum mechanics opens the possibility for developing a new theory of computing wherein the Universal Turing Machine (UTM) performs semantic symbol manipulation and models macroscopic quantum computing. 1. Introduction This paper seeks to relate quantum mechanics to artificial intelligence, human language, and cognition. It is a position paper, reporting some relevant details of a long-term research program currently in progress. In his justly famous Chinese Room Argument (CRA), Searle argued that “we could not give the capacity to understand Chinese or English [that humans evidently have] to a machine where the operation of the machine is solely defined as the instantiation of a computer program.” ([1], p. 422) Searle avoided the need to positively define ‘human understanding’ by relying on an operator (such as himself) who does not understand Chinese in any sense. Skipping the details of this well-known paper, Searle’s main conclusions were as follows: 1. -

Searle's Chinese Room Thought Experiment, the Failure of Meta- and Sub Systemic Understanding, and Some Thoughts About Thought -Experiments

Danish Yearbook of Philosophy, Vol. 42 (2007),75-96 UNGROUNDED SEMANTICS: SEARLE'S CHINESE ROOM THOUGHT EXPERIMENT, THE FAILURE OF META- AND SUB SYSTEMIC UNDERSTANDING, AND SOME THOUGHTS ABOUT THOUGHT -EXPERIMENTS CHRISTIAN BEENFELDT University College, Oxford The Danish National Research Foundation: Center for Subjectivity Research University of Copenhagen 1. Syntax and Semantics in the Chinese Room Argument With the 2002 anthology Views Into the Chinese Room published by Oxford University Press, John Searle's famous Chinese Room Argument was subject to yet another round of debate - some 22 years since its original introduction in an 1980 issue of the Behavioral and Brain Sciences. l From its very first ap pearance the argument clearly touched a nerve - as evidenced by the 27 peer review commentaries that Searle's paper immediately elicited - and in subse quent years, hundreds of articles discussing the argument have been written by philosophers, psychologists, cognitive scientists and Artificial Intelligence re searchers alike, with evaluations of the argument spanning the entire spectrum from the very critical to the highly laudatory.2 Preston goes as far as to charac terize the argument as "contemporary philosophy's best-known argument"3 and Dietrich states that "AI would have no future if Searle is correct."4 Al though both are overselling the point here, there is widespread agreement about the substantial importance of Searle's argument to the issue of machine think ing. As Teng puts it: Searle's ... Chinese room argument has been one of the most celebrated philosophical argu ments in the contemporary philosophy of mind. It is simple and elegant, and is the best known and most-cited philosophical argument against Strong AU 6 Searle's argument runs as follows.