And Analysis 5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Office of the Director of Higher Secondary Education, Housing

Office of the Director of Higher Secondary Education, Housing Board Buildings, Santhi Nagar, Thiruvananthapuram [email protected] Phone No: 2323198 CG&AC/70558/2017/DHSE Dated: 23/05/2017 CIRCULAR Sub: Scouts and Guides–Training for Scout Masters and Guide Captains of Newly selected schools-third batch scheduled-reg Ref: 1. G.O (M S)14/2014/Gl.Edn date 15.01.2014 2. Ltr No.H-1235/2017/KSBSG dated 11-05-2017 of state secretary Kerala state Bharat Scouts and Guides As per reference cited, Government has accorded sanction to start Scouts and Guides unit in Government and Aided Higher Secondary Schools.Accordingly387Schools were provisionally selected for starting Scouts / Guides, out of which 243 schools for both scouts and guides, 74 schools for scouts units and 70 schools for guides units. Units will be sanctioned to schools only after the successful completion of the Basic Training for Scout Master/Guide Captain by the teacher. The Third batch of training is scheduled to conduct from 29th May to 04th June 2017 at State Training Centre, Kerala State Bharat Scouts and Guides, Palode, Thiruvananthapuram for 81 Guide Captains, at Regional Training Centre Nadavathur Kozhikode for 80 Scout Masters A teacher selected as Scout Master and a lady teacher selected as Guide Captain of the selected schools (list attached) should attend the seven days residential programme. The selected teacher should not be in charge of Career Guidance unit, Souhrida Club, NCC, NSS and SPC. Scout Masters/Guide Captains should be in correct and complete uniform as given below: Shirt : A steel grey shirt with two patch pockets with shoulder straps with half sleeves Pants : Navy Blue Pants with loop at 2 inches Head Dress : Dark blue baret cap with official cap badge.Black Socks and Black Shoes with lace may be worn. -

List of Teachers Posted from the Following Schools to Various Examination Centers As Assistant Superintendents for Higher Secondary Exam March 2015

LIST OF TEACHERS POSTED FROM THE FOLLOWING SCHOOLS TO VARIOUS EXAMINATION CENTERS AS ASSISTANT SUPERINTENDENTS FOR HIGHER SECONDARY EXAM MARCH 2015 08001 - GOVT SMT HSS,CHELAKKARA,THRISSUR 1 DILEEP KUMAR P V 08015-GOVT HSS,CHERUTHURUTHY,THRISSUR 04884231495, 9495222963 2 SWAPNA P 08015-GOVT HSS,CHERUTHURUTHY,THRISSUR , 9846374117 3 SHAHINA.K 08035-GOVT. RSR VHSS, VELUR, THRISSUR 04885241085, 9447751409 4 SEENA M 08041-GOVT HSS,PAZHAYANNOOR,THRISSUR 04884254389, 9447674312 5 SEENA P.R 08046-AKM HSS,POOCHATTY,THRISSUR 04872356188, 9947088692 6 BINDHU C 08062-ST ANTONY S HSS,PUDUKAD,THRISSUR 04842331819, 9961991555 7 SINDHU K 08137-GOVT. MODEL HSS FOR GIRLS, THRISSUR TOWN, , 9037873800 THRISSUR 8 SREEDEVI.S 08015-GOVT HSS,CHERUTHURUTHY,THRISSUR , 9020409594 9 RADHIKA.R 08015-GOVT HSS,CHERUTHURUTHY,THRISSUR 04742552608, 9847122431 10 VINOD P 08015-GOVT HSS,CHERUTHURUTHY,THRISSUR , 9446146634 11 LATHIKADEVI L A 08015-GOVT HSS,CHERUTHURUTHY,THRISSUR 04742482838, 9048923857 12 REJEESH KUMAR.V 08015-GOVT HSS,CHERUTHURUTHY,THRISSUR 04762831245, 9447986101 08002 - GOVT HSS,CHERPU,THRISSUR 1 PREETHY M K 08003-GOVT MODEL GHSS, IRINJALAKKUDA, THRISSUR 04802820505, 9496288495 2 RADHIKA C S 08003-GOVT MODEL GHSS, IRINJALAKKUDA, THRISSUR , 9495853650 3 THRESSIA A.O 08005-GOVT HSS,KODAKARA,THRISSUR 04802726280, 9048784499 4 SMITHA M.K 08046-AKM HSS,POOCHATTY,THRISSUR 04872317979, 8547619054 5 RADHA M.R 08050-ST ANTONY S HSS,AMMADAM,THRISSUR 04872342425, 9497180518 6 JANITHA K 08050-ST ANTONY S HSS,AMMADAM,THRISSUR 04872448686, 9744670871 1 7 SREELEKHA.E.S 08050-ST ANTONY S HSS,AMMADAM,THRISSUR 04872343515, 9446541276 8 APINDAS T T 08095-ST. PAULS CONVENT EHSS KURIACHIRA, THRISSUR, 04872342644, 9446627146 680006 9 M.JAMILA BEEVI 08107-SN GHSS, KANIMANGALAM, THRISSUR, 680027 , 9388553667 10 MANJULA V R 08118-TECHNICAL HSS, VARADIAM, THRISSUR, 680547 04872216227, 9446417919 11 BETSY C V 08138-GOVT. -

Chelakkara Assembly Kerala Factbook

Editor & Director Dr. R.K. Thukral Research Editor Dr. Shafeeq Rahman Compiled, Researched and Published by Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. D-100, 1st Floor, Okhla Industrial Area, Phase-I, New Delhi- 110020. Ph.: 91-11- 43580781, 26810964-65-66 Email : [email protected] Website : www.electionsinindia.com Online Book Store : www.datanetindia-ebooks.com Report No. : AFB/KR-061-0619 ISBN : 978-93-5313-530-0 First Edition : January, 2018 Third Updated Edition : June, 2019 Price : Rs. 11500/- US$ 310 © Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical photocopying, photographing, scanning, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. Please refer to Disclaimer at page no. 128 for the use of this publication. Printed in India No. Particulars Page No. Introduction 1 Assembly Constituency -(Vidhan Sabha) at a Glance | Features of Assembly 1-2 as per Delimitation Commission of India (2008) Location and Political Maps Location Map | Boundaries of Assembly Constituency -(Vidhan Sabha) in 2 District | Boundaries of Assembly Constituency under Parliamentary 3-9 Constituency -(Lok Sabha) | Town & Village-wise Winner Parties- 2019, 2016, 2014, 2011 and 2009 Administrative Setup 3 District | Sub-district | Towns | Villages | Inhabited Villages | Uninhabited 10-11 Villages | Village Panchayat | Intermediate Panchayat Demographics 4 Population | Households | Rural/Urban Population | Towns and Villages -

List of Offices Under the Department of Registration

1 List of Offices under the Department of Registration District in Name& Location of Telephone Sl No which Office Address for Communication Designated Officer Office Number located 0471- O/o Inspector General of Registration, 1 IGR office Trivandrum Administrative officer 2472110/247211 Vanchiyoor, Tvpm 8/2474782 District Registrar Transport Bhavan,Fort P.O District Registrar 2 (GL)Office, Trivandrum 0471-2471868 Thiruvananthapuram-695023 General Thiruvananthapuram District Registrar Transport Bhavan,Fort P.O District Registrar 3 (Audit) Office, Trivandrum 0471-2471869 Thiruvananthapuram-695024 Audit Thiruvananthapuram Amaravila P.O , Thiruvananthapuram 4 Amaravila Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2234399 Pin -695122 Near Post Office, Aryanad P.O., 5 Aryanadu Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0472-2851940 Thiruvananthapuram Kacherry Jn., Attingal P.O. , 6 Attingal Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0470-2623320 Thiruvananthapuram- 695101 Thenpamuttam,BalaramapuramP.O., 7 Balaramapuram Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2403022 Thiruvananthapuram Near Killippalam Bridge, Karamana 8 Chalai Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2345473 P.O. Thiruvananthapuram -695002 Chirayinkil P.O., Thiruvananthapuram - 9 Chirayinkeezhu Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0470-2645060 695304 Kadakkavoor, Thiruvananthapuram - 10 Kadakkavoor Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0470-2658570 695306 11 Kallara Trivandrum Kallara, Thiruvananthapuram -695608 Sub Registrar 0472-2860140 Kanjiramkulam P.O., 12 Kanjiramkulam Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2264143 Thiruvananthapuram- 695524 Kanyakulangara,Vembayam P.O. 13 -

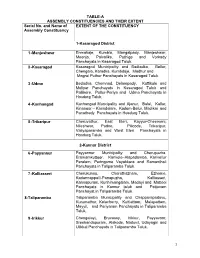

List of Lacs with Local Body Segments (PDF

TABLE-A ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCIES AND THEIR EXTENT Serial No. and Name of EXTENT OF THE CONSTITUENCY Assembly Constituency 1-Kasaragod District 1 -Manjeshwar Enmakaje, Kumbla, Mangalpady, Manjeshwar, Meenja, Paivalike, Puthige and Vorkady Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 2 -Kasaragod Kasaragod Municipality and Badiadka, Bellur, Chengala, Karadka, Kumbdaje, Madhur and Mogral Puthur Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 3 -Udma Bedadka, Chemnad, Delampady, Kuttikole and Muliyar Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk and Pallikere, Pullur-Periya and Udma Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 4 -Kanhangad Kanhangad Muncipality and Ajanur, Balal, Kallar, Kinanoor – Karindalam, Kodom-Belur, Madikai and Panathady Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 5 -Trikaripur Cheruvathur, East Eleri, Kayyur-Cheemeni, Nileshwar, Padne, Pilicode, Trikaripur, Valiyaparamba and West Eleri Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 2-Kannur District 6 -Payyannur Payyannur Municipality and Cherupuzha, Eramamkuttoor, Kankole–Alapadamba, Karivellur Peralam, Peringome Vayakkara and Ramanthali Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 7 -Kalliasseri Cherukunnu, Cheruthazham, Ezhome, Kadannappalli-Panapuzha, Kalliasseri, Kannapuram, Kunhimangalam, Madayi and Mattool Panchayats in Kannur taluk and Pattuvam Panchayat in Taliparamba Taluk. 8-Taliparamba Taliparamba Municipality and Chapparapadavu, Kurumathur, Kolacherry, Kuttiattoor, Malapattam, Mayyil, and Pariyaram Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 9 -Irikkur Chengalayi, Eruvassy, Irikkur, Payyavoor, Sreekandapuram, Alakode, Naduvil, Udayagiri and Ulikkal Panchayats in Taliparamba -

Ground Water Year Book of Kerala (2018-19)

Ground Water Year Book of Kerala (2018-19) TECHNICAL REPORT SERIES GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF JALSHAKTI CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD GROUND WATER YEAR BOOK OF KERALA (2018-2019) KERALA REGION THIRUVANANTHAPURAM SEPTEMBER 2019 Ground Water Year Book of Kerala (2018-19) GROUND WATER YEAR BOOK OF KERALA (2018-2019) Table of Contents 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 1 2. Hydrogeology......................................................................................................................... 4 2.1 Physiography…………………………….. ............................................................................. 4 2.2 Geology…………………………….. .................................................................................... 4 2.3 Occurrence of Groundwater…………. .................................................................................. 5 3. Rainfall distribution in Kerala during 2018-19 .................................................................... 7 3.1 Introduction…………………….. .......................................................................................... 7 3.2 Annual rainfall distribution…………..................................................................................... 7 3.3 Monthly rainfall distribution… .............................................................................................. 7 3.4 Normal rainfall vs. actual rainfall.......................................................................................... -

Dictionary of Martyrs: India's Freedom Struggle

DICTIONARY OF MARTYRS INDIA’S FREEDOM STRUGGLE (1857-1947) Vol. 5 Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu & Kerala ii Dictionary of Martyrs: India’s Freedom Struggle (1857-1947) Vol. 5 DICTIONARY OF MARTYRSMARTYRS INDIA’S FREEDOM STRUGGLE (1857-1947) Vol. 5 Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu & Kerala General Editor Arvind P. Jamkhedkar Chairman, ICHR Executive Editor Rajaneesh Kumar Shukla Member Secretary, ICHR Research Consultant Amit Kumar Gupta Research and Editorial Team Ashfaque Ali Md. Naushad Ali Md. Shakeeb Athar Muhammad Niyas A. Published by MINISTRY OF CULTURE, GOVERNMENT OF IDNIA AND INDIAN COUNCIL OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH iv Dictionary of Martyrs: India’s Freedom Struggle (1857-1947) Vol. 5 MINISTRY OF CULTURE, GOVERNMENT OF INDIA and INDIAN COUNCIL OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH First Edition 2018 Published by MINISTRY OF CULTURE Government of India and INDIAN COUNCIL OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH 35, Ferozeshah Road, New Delhi - 110 001 © ICHR & Ministry of Culture, GoI No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ISBN 978-81-938176-1-2 Printed in India by MANAK PUBLICATIONS PVT. LTD B-7, Saraswati Complex, Subhash Chowk, Laxmi Nagar, New Delhi 110092 INDIA Phone: 22453894, 22042529 [email protected] State Co-ordinators and their Researchers Andhra Pradesh & Telangana Karnataka (Co-ordinator) (Co-ordinator) V. Ramakrishna B. Surendra Rao S.K. Aruni Research Assistants Research Assistants V. Ramakrishna Reddy A.B. Vaggar I. Sudarshan Rao Ravindranath B.Venkataiah Tamil Nadu Kerala (Co-ordinator) (Co-ordinator) N. -

Senior Clerk

Government of Kerala Department: Agriculture Norms Based General Transfer for CLERK Sl. PEN Name Designation Office Office Protection If any No Transfered from Transfered to Post/Cadre Name: CLERK 1 182716 sreejith LD Clerk (15 Yrs Not BANANA NURSERY, STATE SEED FARM, ULLOOR,Thiruvananthapuram Inter Caste married Employee Qualified) PERINGAMALA,Thiruvananthapuram 2 283663 PRAKASAN P K Clerk PRINCIPAL AGRICULTURAL OFFICE Asst.Director of Agricultural office,Mala,Thrissur THRISSUR,Thrissur 3 336931 Bindu K LD Clerk (15 Yrs Not ASST.DIRECTOR OF AGRICULTURE COCONUT NURSERY PALAYAD,Kannur Qualified) PAYYANNUR,Kannur 4 336966 Suresh U K LD Clerk (22 Yrs Not PRINCIPAL AGRICULTURAL OFFICE, ASSISTANT DIRECTOR OF Qualified) KANNUR,Kannur AGRICULTURE.PERAVOOR,Kannur 5 356441 Omana P K LD Clerk (8 Yrs HG Not OFFICE OF THE O/O A D AGRICULTURE, VELLANGALLUR,Thrissur Qualified) ASST.EXE.ENGINEER(AGRI),THRISSUR,Thrissur 6 357023 Lissy Sebastian Clerk STATE SEED FARM, KODASSERY,Thrissur ASSTDIRECTOR OF AGRL ALUVA,Ernakulam 7 357081 Poulose K P Clerk PRINCIPAL AGRICULTURAL OFFICE STATE SEED FARM, KODASSERY,Thrissur THRISSUR,Thrissur 8 357388 Mayamol S R LD Clerk (15 Yrs O/o The Assistant Executive Engineer (Agri) PRINCIPAL AGRICULTURE OFFICE, Qualified) Kureepuzha, Klm,Kollam PATHANAMTHITTA,Pathanamthitta 9 379803 Siji Kumar B Clerk ASST DIRECTOR OF AGRI Principal Agricultural Office, Kasaragod,Kasaragod CHADAYAMANGALAM,Kollam 10 384094 SIVAPRASAD N P Clerk DIST AGRI FARM CHELAKKARA,Thrissur ASSISTANT DIRECTOR OF SC/ST AGRICULTURE,TAVANUR,Malappuram 11 -

Covid-19 Outbreak Control and Prevention State Cell Health & Family

COVID-19 OUTBREAK CONTROL AND PREVENTION STATE CELL HEALTH & FAMILY WELFARE DEPARTMENT GOVT. OF KERALA www.health.kerala.gov.in www.dhs.kerala.gov.in [email protected] Date: 18/08/2021 Time: 02:00 PM The daily COVID-19 bulletin of the Department of Health and Family Welfare, Government of Kerala summarizes the COVID-19 situation in Kerala. The details of hotspots identified are provided in Annexure-1 for quick reference. The bulletin also contains links to various important documents, guidelines, and websites for references. OUR HEALTH OUR RESPONSIBILITY • Maintain a distance of at least two metres with all people all the time. • Always wear clean face mask appropriately everywhere all the time • Perform hand hygiene after touching objects and surfaces all the time. • Perform hand hygiene before and after touching your face. • Observe cough and sneeze hygiene always • Stay Home; avoid direct social interaction and avoid travel • Protect the elderly and the vulnerable- Observe reverse quarantine • Do not neglect even mild symptoms; seek health care “OUR HEALTH OUR RESPONSIBILITY” Page 1 of 22 PART- 1 SUMMARY OF COVID CASES AND DEATH Table 1. Summary of COVID-19 cases till 17/08/2021 New persons New Persons New persons Positive Recovered added to added to Home, in Hospital Deaths cases patients Quarantine/ Institution Isolation Isolation quarantine 3724030 3529465 38377 27881 2409 18870 Table 2. Summary of new COVID-19 cases (last 24 hours) New Persons New persons New persons added to in Hospital Positive Recovered added to Home, Isolation Deaths cases patients Quarantine/ Institution Isolation quarantine 21427 18731 35995 33770 2225 179 Table 3. -

Kerala La, 2021

LIST OF DEPLOYED EXPENDITURE OBSERVERS : GE to KERALA LA, 2021 Sl. No. Observer Observer Name Service Year AC Name Email Contact No. Code 1 R-22553 Mr. Sanjoy Paul IRS 2007 1-MANJESHWAR[Kasaragod],2- [email protected] 8986912289 KASARAGOD[Kasaragod] 2 R-20348 Mr. M. Sathishkumar IRS(C&CE) 2010 3-UDMA[Kasaragod],4- [email protected] 8939726010 KANHANGAD[Kasaragod],5- TRIKARIPUR[Kasaragod] 3 R-28500 Dr. Megha Bhargava IRS 2012 6-PAYYANNUR[Kannur],7- [email protected] 9969232929 KALLIASSERI[Kannur],8- TALIPARAMBA[Kannur] 4 R-28524 Mr. Birendra Kumar IRS 2013 9-IRIKKUR[Kannur],10- [email protected] 7588630063 AZHIKODE[Kannur],11- KANNUR[Kannur],12- DHARMADAM[Kannur] 5 R-20865 Mr. Sudhanshu Shekhar IRS 2010 13-THALASSERY[Kannur],14- [email protected] 9477331024 Gautam KUTHUPARAMBA[Kannur],15- MATTANNUR[Kannur],16- PERAVOOR[Kannur] 6 R-21006 Mr. S.Sundar Rajan, IRS IRS 2007 17- [email protected] 8762300070 MANANTHAVADY[Wayanad],18- SULTHANBATHERY[Wayanad], 19-KALPETTA[Wayanad] 7 R-18700 Mr. Mohd. Salik Parwaiz IRS(C&CE) 2009 20-VADAKARA[Kozhikode],21- [email protected] 9407683088 KUTTIADI[Kozhikode],22- NADAPURAM[Kozhikode],23- QUILANDY[Kozhikode] 8 R-21597 Mr. Shree Ram Vishnoi IRS(C&CE) 2011 24-PERAMBRA[Kozhikode],25- [email protected] 9001958758 BALUSSERI[Kozhikode],26- ELATHUR[Kozhikode],27- KOZHIKODE NORTH[Kozhikode] 9 R-22392 Mr. Vibhor Badoni IRS 2009 28-KOZHIKODE [email protected] 9969238168 SOUTH[Kozhikode],29- BEYPORE[Kozhikode],30- KUNNAMANGALAM[Kozhikode], 31-KODUVALLY[Kozhikode],32- THIRUVAMBADY[Kozhikode] 10 R-23005 Mr. Ashish Kumar IRS(C&CE) 2010 34-ERANAD[Malappuram],35- [email protected] 9523813876 NILAMBUR[Malappuram],36- WANDOOR[Malappuram],37- MANJERI[Malappuram] 11 R-20319 Mr. -

District Wise IT@School Master District School Code School Name Thiruvananthapuram 42006 Govt

District wise IT@School Master District School Code School Name Thiruvananthapuram 42006 Govt. Model HSS For Boys Attingal Thiruvananthapuram 42007 Govt V H S S Alamcode Thiruvananthapuram 42008 Govt H S S For Girls Attingal Thiruvananthapuram 42010 Navabharath E M H S S Attingal Thiruvananthapuram 42011 Govt. H S S Elampa Thiruvananthapuram 42012 Sr.Elizabeth Joel C S I E M H S S Attingal Thiruvananthapuram 42013 S C V B H S Chirayinkeezhu Thiruvananthapuram 42014 S S V G H S S Chirayinkeezhu Thiruvananthapuram 42015 P N M G H S S Koonthalloor Thiruvananthapuram 42021 Govt H S Avanavancheri Thiruvananthapuram 42023 Govt H S S Kavalayoor Thiruvananthapuram 42035 Govt V H S S Njekkad Thiruvananthapuram 42051 Govt H S S Venjaramood Thiruvananthapuram 42070 Janatha H S S Thempammood Thiruvananthapuram 42072 Govt. H S S Azhoor Thiruvananthapuram 42077 S S M E M H S Mudapuram Thiruvananthapuram 42078 Vidhyadhiraja E M H S S Attingal Thiruvananthapuram 42301 L M S L P S Attingal Thiruvananthapuram 42302 Govt. L P S Keezhattingal Thiruvananthapuram 42303 Govt. L P S Andoor Thiruvananthapuram 42304 Govt. L P S Attingal Thiruvananthapuram 42305 Govt. L P S Melattingal Thiruvananthapuram 42306 Govt. L P S Melkadakkavur Thiruvananthapuram 42307 Govt.L P S Elampa Thiruvananthapuram 42308 Govt. L P S Alamcode Thiruvananthapuram 42309 Govt. L P S Madathuvathukkal Thiruvananthapuram 42310 P T M L P S Kumpalathumpara Thiruvananthapuram 42311 Govt. L P S Njekkad Thiruvananthapuram 42312 Govt. L P S Mullaramcode Thiruvananthapuram 42313 Govt. L P S Ottoor Thiruvananthapuram 42314 R M L P S Mananakku Thiruvananthapuram 42315 A M L P S Perumkulam Thiruvananthapuram 42316 Govt. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Thrissur City District from 31.01.2021To06.02.2021

Accused Persons arrested in Thrissur City district from 31.01.2021to06.02.2021 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 ARRESTED - Thrissur Principal SHA MANZIL 06-02-2021 114/2021 U/s SALISH. N.S. SHAHUL 28, M.G.ROAD West District 1 SHAFI KOORKKENCHER at 19:45 22(b)(C) of ISHO OF HAMEED Male THRISSUR (Thrissur Sessions Y.P.O. THRISSUR Hrs NDPS Act POLICE City) Court, Thrissur Pathamkulam 85/2021 U/s House, Kaliyaroad PRAVEEN KJ 06-02-2021 118(e) of KP CHELAKKA 42, Desom, SI OF POLICE BAILED BY 2 Noushad Ali Kaliyaroad at 19:58 Act & 3(1) RA (Thrissur Male Pangarappilly CHELAKKA POLICE Hrs r/w 181 MV City) village, Chelakkara RA PS Act Thrissur Rural 84/2021 U/s Puthukulam House, PRAVEEN KJ 06-02-2021 118(e) of KP CHELAKKA Abdul 48, Kaliyarode Desom, SI OF POLICE BAILED BY 3 Mujeeb Kaliyaroad at 19:48 Act & 3(1) RA (Thrissur Rahman Male Pangarappilly CHELAKKA POLICE Hrs r/w 181 MV City) village, Chelakkara RA PS Act PANAKKAL(H) 06-02-2021 15/2021 U/s Traffic MADHAVA 40, PATTURAIK RAMAKRISH BAILED BY 4 SUDHEESH KOLAZHI at 18:50 279 IPC & 185 (Thrissur N Male KAL NAN POLICE ATHEKKAD Hrs MV ACT City) kalathil Thrissur Volga Hotel 06-02-2021 168/2021 U/s Sreedharan 49, House,Thozhuvano East SINOJ SI OF BAILED BY 5 MANOJ ,P.O Road at 18:25 7 & 8 of KG Nair Male or,Valanchery,,Katti (Thrissur POLICE POLICE