Coul Links Public Inquiry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ipas in Scotland • 2

IPAs in Scotland • 2 • 5 • 6 • 3 • 4 • 15 • 10 • 11 • 14 • 16 • 12 • 13 • 9 • 7 • 8 • 17 • 19 • 21 • 26 • 29 • 23 • 25 • 27 31 • • 33 • 18 • 28 • 32 • 24 • 20 • 22 • 30 • 40 • 34 • 39 • 41 • 45 • 35 • 37 • 38 • 44 • 36 • 43 • 42 • 47 • 46 2 Contents Contents • 1 4 Foreword 6 Scotland’s IPAs: facts and figures 12 Protection and management 13 Threats 14 Land use 17 Planning and land use 18 Land management 20 Rebuilding healthy ecosystems 21 Protected areas Code IPA name 22 Better targeting of 1 Shetland 25 Glen Coe and Mamores resources and support 2 Mainland Orkney 26 Ben Nevis and the 24 What’s next for 3 Harris and Lewis Grey Corries Scotland’s IPAs? 4 Ben Mor, Assunt/ 27 Rannoch Moor 26 The last word Ichnadamph 28 Breadalbane Mountains 5 North Coast of Scotland 29 Ben Alder and Cover – Glen Coe 6 Caithness and Sutherland Aonach Beag ©Laurie Campbell Peatlands 30 Crieff Woods 7 Uists 31 Dunkeld-Blairgowrie 8 South West Skye Lochs 9 Strathglass Complex 32 Milton Wood 10 Sgurr Mor 33 Den of Airlie 11 Ben Wyvis 34 Colonsay 12 Black Wood of Rannoch 35 Beinn Bheigier, Islay 13 Moniack Gorge 36 Isle of Arran 14 Rosemarkie to 37 Isle of Cumbrae Shandwick Coast 38 Bankhead Moss, Beith 15 Dornoch Firth and 39 Loch Lomond Woods Morrich More 40 Flanders Moss 16 Culbin Sands and Bar 41 Roslin Glen 17 Cairngorms 42 Clearburn Loch 18 Coll and Tiree 43 Lochs and Mires of the 19 Rum Ale and Ettrick Waters 20 Ardmeanach 44 South East Scotland 21 Eigg Basalt Outcrops 22 Mull Oakwoods 45 River Tweed 23 West Coast of Scotland 46 Carsegowan Moss 24 Isle of Lismore 47 Merrick Kells Citation Author Plantlife (2015) Dr Deborah Long with editorial Scotland’s Important comment from Ben McCarthy. -

Editor's Preface

EDITOR'S PREFACE 'Firthlands' embraces those eastern lowlands clustered around the Dor noch, Cromarty, Beauly and Inner Moray Firths. Firthlands of Ross and Sutherland focuses more particularly on the gentle and fertile country around the Dornoch and Cromarty Firths- from Golspie and Loch Fleet in the north, to Bonar Bridge, Tain and the Easter Ross peninsula, across to Cromarty and the Black Isle, and up-firth to Dingwall and Muir of Ord. Of the twelve contrasting chapters, one provides a broad geological background to the area and highlights landscape features as they have evolved through time- the Great Glen and Helmsdale Faults, glacially deepened and drowned river valleys, raised beaches, wave-formed shingle barriers. And it is the underlying geology that gave rise to the shape of early habitational and communications networks, to the Brora coal-mines and to the spa waters of Strathpeffer, to stone and sand and gravel and peat for extraction, to the nature and balance of agricultural practice, to the oil and gas fields off the coast. Such economic activity is most apparent for relatively recent times, so that six chapters concentrate on the seventeenth to early twentieth cen turies. Some explore trade and family links across to Moray and the Baltic, as well as with other parts of Scotland and beyond; others concentrate on changes in settlement patterns, agriculture and stock-rearing, both in the firthlands and their highland hinterland; yet others are more concerned with a particularly rich architectural heritage.In each case, there is a weave between Highlander and Lowlander, spiced with the ever-increasing exposure of the north to southern influences and pressures. -

Scottish Birds

ISSN 0036-9144 SCOTTISH BIRDS THE JOURNAL OF THE SCOTTISH ORNITHOLOGISTS' CLUB Vol. 10 No. 7 AUTUMN 1979 ORNITHOLIDAYS Member of The Association 1980 of British Travel Agents Holidays organised by Birdwatchers for Birdwatchers INDIA (North) INDIA (Assam) NOVA SCOTIA THE SEYCHELLES AUSTRIAN ALPS TANZANIA PORTUGAL MOROCCO CENTRAL WALES MALAWI ISLES OF SCILLY SRI LANKA ISLE OF MULL VANCOUVER & ROCKIES ISLE OF ISLAY THE GAMBIA THE CAIRNGORMS MAJORCA HEBRIDEAN CRUISES S.W. SPAIN DORSET GREECE SUFFOLK THE CAMARGUE FARNES & BASS ROCK LAKE NEUSIEDL YUGOSLAVIA Particulars sent on receipt of 8p stamp to : LAWRENCE G. HOLLOWAY ORNITHOLlDAYS (Regd) (WESSEX TRAVEL CENTRE) 1/3 VICTORIA DRIVE, BOGNOR REGIS, SUSSEX, England, P021 2PW Telephone 02433 21230 Telegrams : Ornitholidays Bognor Regis. ·000000000000000000000001 COLOUR SLIDES BINOCULAR We are now able to supply REPAIRS slides of most British Birds from our own collection, and from that of the R.S.P.B. CHARLES FRANK LID. Send 25p for sample slide are pleased to offer a special and our lists covering these concession to members of the Scot and birds of Africa-many tish Ornithologists' Club. Servicing fine studies and close-ups. and repairs of all makes of binocu lars will be undertaken at special FOR HIRE prices. Routine cleaning and re We have arranged to hire out aligning costs £5 + £1 post, packing slides of the R.S.P.B. These and insurance. Estimates will be are in sets of 25 at 60p in provided should additional work cluding postage & V.A.T. per be required. night's hire. Birds are group ed according to their natural Send to The Service Manager habitats. -

Site Condition Monitoring for Otters (Lutra Lutra) in 2011-12

Scottish Natural Heritage Commissioned Report No. 521 Site condition monitoring for otters (Lutra lutra) in 2011-12 COMMISSIONED REPORT Commissioned Report No. 521 Site condition monitoring for otters (Lutra lutra) in 2011-12 For further information on this report please contact: Rob Raynor Scottish Natural Heritage Great Glen House INVERNESS IV3 8NW Telephone: 01463 725000 E-mail: [email protected] This report should be quoted as: Findlay, M., Alexander, L. & Macleod, C. 2015. Site condition monitoring for otters (Lutra lutra) in 2011-12. Scottish Natural Heritage Commissioned Report No. 521. This report, or any part of it, should not be reproduced without the permission of Scottish Natural Heritage. This permission will not be withheld unreasonably. The views expressed by the author(s) of this report should not be taken as the views and policies of Scottish Natural Heritage. © Scottish Natural Heritage 2015. COMMISSIONED REPORT Summary Site condition monitoring for otters (Lutra lutra) in 2011-12 Commissioned Report No. 521 Project No: 12557 and 13572 Contractor: Findlay Ecology Services Ltd. Year of publication: 2015 Keywords Otter; Lutra lutra; monitoring; Special Area of Conservation. Background 44 Special Areas of Conservation (SACs) for which otter is a qualifying interest were surveyed during 2011 and 2012 to collect evidence to inform an assessment of the condition of each SAC. 73 sites outside the protected areas network were also surveyed. The combined data were used to look for trends in the recorded otter population in Scotland since the first survey of 1977-79. Using new thresholds for levels of occupancy, and other targets agreed with SNH for the current report, the authors assessed 34 SACs as being in favourable condition, and 10 sites were assessed to be in unfavourable condition. -

Scottish Nature Omnibus Survey August 2019

Scottish Natural Heritage Scottish Nature Omnibus Survey August 2019 The general public’s perceptions of Scotland’s National Nature Reserves Published: December 2019 People and Places Scottish Natural Heritage Great Glen House Leachkin Road Inverness IV3 8NW For further information please contact [email protected] 1. Introduction The Scottish Nature Omnibus (SNO) is a survey of the adult population in Scotland which now runs on a biennial basis. It was first commissioned by SNH in 2009 to measure the extent to which the general public is engaged with SNH and its work. Seventeen separate waves of research have been undertaken since 2009, each one based on interviews with a representative sample of around 1,000 adults living in Scotland; interviews with a booster sample of around 100 adults from ethnic minority groups are also undertaken in each survey wave to enable us to report separately on this audience. The SNO includes a number of questions about the public’s awareness of and visits to National Nature Reserves (see Appendix). This paper summarises the most recent findings from these questions (August 2019), presenting them alongside the findings from previous waves of research. Please note that between 2009 and 2015 the SNO was undertaken using a face to face interview methodology. In 2017, the survey switched to an on-line interview methodology, with respondents sourced from members of the public who had agreed to be part of a survey panel. While the respondent profile and most question wording remained the same, it should be borne in mind when comparing the 2017 and 2019 findings with data from previous years that there may be differences in behaviour between people responding to a face to face survey and those taking part in an online survey that can impact on results. -

NORTH of SCOTLAND COLLEGE of AGRICULTURE School of Agriculture, Aberdeen Agricultural Economics Department (

NORTH OF SCOTLAND COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE School of Agriculture, Aberdeen Agricultural Economics Department ( G1ANNINT NDATTOM OF AC.7 ICIGVILTU LI JUL 12.3 Farm Crop Irrigation in the North of Scotland 1964 and 1965 by J. S. Bon;, M.Sc. June, 1966 Economic Retort No. 117 Price 31- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Agricultural Economics Department of the North of Scotland College of Agriculture wishes to thank those farmers and members of the County Advisory Staff who supplied the records and information on which this report is based. THE NORTH OF SCOTLAND CO D E OF AGRICULTURE AGRICULTURAL ECONavlICS DEPARTMENT FARM CROP IRRIGATION IN THE NORTH OF SCOTLAND 1964. arrl 1965 by J. S. Bone. ivl.Sc, June, 1966. FARM CROP IRRIGATION IN THE NORTH OP. SCOTLAND 1964. AND 1965 CONTENTS Pape INTRCIDUCTION Weather During Survey Period. 1964. and 1965 • The Sa41.e 10 STJRVEY RESULTS 13 Water Sources 13 Equipment 15 Utilisation of Equipment 1964. and. 1965 17 IRRIGATION COSTS AND RETURNS - IN THE NORTH 'OF SCOTLAND 19 &LEARY AND CONCLUSIONS 26 APPENDICES Appendix I - River Purification Board. Areas, North of Scotland. College of Agriculture Mainland. Area. 29 Appendix II - Acreage of HOrticultural Crops at June.,- 1964., North of Scotland. College of Agriculture Area, 30 Appendix III - Total Acreage of Agricultural Crops at June,"1964., North of Scotland. College of Agriculture Area. 31 Appendix IV - Glossary of Terms-Used. 32 BIBLICGRA.PHY 33 • LIST OF TABLES Table Page 1 Frequency of Irrigation Need - Inverness (Dalcross) Area, April-September 4. 2 Frequency of Irrigation Need. - Inverness (Dalcross) Area, April-July 3 Irrigation Sets in the North of Scotland. -

The Invertebrate Fauna of Dune and Machair Sites In

INSTITUTE OF TERRESTRIAL ECOLOGY (NATURAL ENVIRONMENT RESEARCH COUNCIL) REPORT TO THE NATURE CONSERVANCY COUNCIL ON THE INVERTEBRATE FAUNA OF DUNE AND MACHAIR SITES IN SCOTLAND Vol I Introduction, Methods and Analysis of Data (63 maps, 21 figures, 15 tables, 10 appendices) NCC/NE RC Contract No. F3/03/62 ITE Project No. 469 Monks Wood Experimental Station Abbots Ripton Huntingdon Cambs September 1979 This report is an official document prepared under contract between the Nature Conservancy Council and the Natural Environment Research Council. It should not be quoted without permission from both the Institute of Terrestrial Ecology and the Nature Conservancy Council. (i) Contents CAPTIONS FOR MAPS, TABLES, FIGURES AND ArPENDICES 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 OBJECTIVES 2 3 METHODOLOGY 2 3.1 Invertebrate groups studied 3 3.2 Description of traps, siting and operating efficiency 4 3.3 Trapping period and number of collections 6 4 THE STATE OF KNOWL:DGE OF THE SCOTTISH SAND DUNE FAUNA AT THE BEGINNING OF THE SURVEY 7 5 SYNOPSIS OF WEATHER CONDITIONS DURING THE SAMPLING PERIODS 9 5.1 Outer Hebrides (1976) 9 5.2 North Coast (1976) 9 5.3 Moray Firth (1977) 10 5.4 East Coast (1976) 10 6. THE FAUNA AND ITS RANGE OF VARIATION 11 6.1 Introduction and methods of analysis 11 6.2 Ordinations of species/abundance data 11 G. Lepidoptera 12 6.4 Coleoptera:Carabidae 13 6.5 Coleoptera:Hydrophilidae to Scolytidae 14 6.6 Araneae 15 7 THE INDICATOR SPECIES ANALYSIS 17 7.1 Introduction 17 7.2 Lepidoptera 18 7.3 Coleoptera:Carabidae 19 7.4 Coleoptera:Hydrophilidae to Scolytidae -

SOILS in EASTER ROSS 1. the Black Isle (Part O F Sheets 83, 84, 93 and 94) 2. Cromarty and Invergordon (Sheet 94) TECHNICAL REPO

SOILS IN EASTER ROSS 1. The Black Isle (part of Sheets 83, 84, 93 and 94) 2. Cromarty and Invergordon (Sheet 94) TECHNICAL REPORT NO. 1 The Macaulay Institute for Soil Research, Crai giebuckler, ABERDEEN AB9 2QJ Scotland Tel: 0224 38611 Preface The two reports covering soils in Easter Ross are edited versions of general accounts, written by J.C.C. Romans, which appeared in the Macaulay Institute for Soil Research Annual Reports Nos. 38 TL first deals .w.fth AL- aiid 40. Lrie area covered by the Biack isle soil map (Parts of Sheets 83, 84, 93 and 94) and the second the area covered by the Cromarty and Invergordon soil map (Sheet 94). A bulletin describing the soils of the Black Isle will be pub1 i shed 1 ater this year. The Macaulay Institute for Soil Research, Aberdeen. July 1984 1. THE BLACK ISLE (part of Sheets 83, 84, 93 and 94) -rL - ne Biack Isle fs a narrow peninsuia in Easter ROSS about 20 miles long lying between the Cromarty Firth and the Moray Firth. Its western boundary is taken to be the road between the Inverness district boundary and Conon Bridge. It has an area of about 280 square kilometres with a width of 7 or 8 miles in the broadest part, narrowing to 4 miles near Rosemarkie, and to less than 2 miles near Cromarty. When viewed from the hills on the north side of the Crornarty Firth the Black Isle stands out long, low and smooth in outline, with a broad central spine rising to over 240 metres at the summit of Mount Eagle. -

The Demo Version

Æbucurnig Dynbær Edinburgh Coldingham c. 638 to Northumbria 8. England and Wales GODODDIN HOLY ISLAND Lindisfarne Tuidi Bebbanburg about 600 Old Melrose Ad Gefring Anglo-Saxon Kingdom NORTH CHANNEL of Northumbria BERNICIA STRATHCLYDE 633 under overlordship Buthcæster Corebricg Gyruum * of Northumbria æt Rægeheafde Mote of Mark Tyne Anglo-Saxon Kingdom Caerluel of Mercia Wear Luce Solway Firth Bay NORTHHYMBRA RICE Other Anglo-Saxon united about 604 Kingdoms Streonæshalch RHEGED Tese Cetreht British kingdoms MANAW Hefresham c 624–33 to Northumbria Rye MYRCNA Tribes DEIRA Ilecliue Eoforwic NORTH IRISH Aire Rippel ELMET Ouse SEA SEA 627 to Northumbria æt Bearwe Humbre c 627 to Northumbria Trent Ouestræfeld LINDESEGE c 624–33 to Northumbria TEGEINGL Gæignesburh Rhuddlan Mærse PEC- c 600 Dublin MÔN HOLY ISLAND Llanfaes Deganwy c 627 to Northumbria SÆTE to Mercia Lindcylene RHOS Saint Legaceaster Bangor Asaph Cair Segeint to Badecarnwiellon GWYNEDD WREOCAN- IRELAND Caernarvon SÆTE Bay DUNODING MIERCNA RICE Rapendun The Wash c 700 to Mercia * Usa NORTHFOLC Byrtun Elmham MEIRIONNYDD MYRCNA Northwic Cardigan Rochecestre Liccidfeld Stanford Walle TOMSÆTE MIDDIL Bay POWYS Medeshamstede Tamoworthig Ligoraceaster EAST ENGLA RICE Sæfern PENCERSÆTE WATLING STREET ENGLA * WALES MAGON- Theodford Llanbadarn Fawr GWERTH-MAELIENYDD Dommoceaster (?) RYNION RICE SÆTE Huntandun SUTHFOLC Hamtun c 656 to Mercia Beodericsworth CEREDIGION Weogornaceaster Bedanford Grantanbrycg BUELLT ELFAEL HECANAS Persore Tovecestre Headleage Rendlæsham Eofeshamm + Hereford c 600 GipeswicSutton Hoo EUIAS Wincelcumb to Mercia EAST PEBIDIOG ERGING Buccingahamm Sture mutha Saint Davids BRYCHEINIOG Gleawanceaster HWICCE Heorotford SEAXNA SAINT GEORGE’SSaint CHANNEL DYFED 577 to Wessex Ægelesburg * Brides GWENT 628 to Mercia Wæclingaceaster Hetfelle RICE Ythancæstir Llanddowror Waltham Bay Cirenceaster Dorchecestre GLYWYSING Caerwent Wealingaford WÆCLINGAS c. -

Lesgrampi an Mo Untains Ord Hill

2 PENTLA ND Dunnet Head FI RT Cape Wrath H Scrabster Duncansby Head Strathy Point John Butt of Lewis / Durness A836 bha Robhanais Melvich o’ Groats Port of Ness / Thurso Port Nis A99 A838 A836 Bettyhill Sinclair’s Bay s A838 L Eriboll Tongue A9 A857 Hope A882 L Kyle of North-west Loch Wick A Tongue Loyal 8 Sutherland 10–13 hour 5 A897 7 Scourie R Naver h Eddrachillis A894 River Thurso A99 oway / Bay abhagh Eye Peninsula / Altnaharra L Naver Lybster A866 An Rubha A836 Kinbrace A837 Dunbeath A838 Enard A9 Bay Lochinver NORTHMINCH Inchnadamph 6-7 hours Assynt- Loch Shin 3 hours Coigach Ledmore Helmsdale Lairg A835 A837 Oykel A839 Bridge A839 A9 Brora R FIRTH R Oykel Shin A837 A836 Golspie Ullapool ay / Bonar Bridge igh A832 L Broom A949 Dornoch MORAY S R Carron E Dornoch A836 Dornoch Firth Fionn Firth L Loch Tain A835 SLEEPIESHILL Gairloch Loch Maree A9 Lossiemouth Alness A832 Loch Invergordon Spey Bay Cullen Kinnaird Head Trotternish Fannich A942 Firth Buckie Banff Fraserburgh Uig A862 Cromarty Elgin ch Kinlochewe A832 Black A96 Portsoy Rona Wester Ross Dingwall A98 ort y Wt A832 a Cromarty A90 s Nairn A834 A9 A941 A98 a A981 A87 A855 Achnasheen Fortrose a Forres d A896 R A96 n A835 Aberchirder Spey f Keith u o Shieldaig Muir of Ord o A950 Rothes R A95 d 50 S A890A89 A940 A97 Mintlaw A95 Turriff n r A952 Peterhead u ly e ORD HILL au Charlestown vegan o e R Nairn A947 A939 n B S of Aberlour n I HIGHLAHIGHLHIGHLANDHIGH R A862 Inverness A920 A982 Portree Loch A948 A863 Loch Monar R Farrar A96 Lochcarron Carron A82 A9 Huntly A90 Raasay A833 -

Mapping Farmland Wader Distributions and Population Change to Identify Wader Priority Areas for Conservation and Management Action

Mapping farmland wader distributions and population change to identify wader priority areas for conservation and management action Scott Newey1*, Debbie Fielding1, and Mark Wilson2 1. The James Hutton Institute, Aberdeen, AB15 8QH 2. The British Trust for Ornithology Scotland, Stirling, FK9 4NF * [email protected] Introduction Many birds have declined across Scotland and the UK as a whole (Balmer et al. 2013, Eaton et al. 2015, Foster et al. 2013, Harris et al. 2017). These include five species of farmland wader; oystercatcher, lapwing, curlew, redshank and snipe. All of these have all been listed as either red or amber species on the UK list of birds of conservation concern (Harris et al. 2017, Eaton et al. 2015). Between 1995 and 2016 both lapwing and curlew declined by more than 40% in the UK (Harris et al. 2017). The UK harbours an estimated 19-27% of the curlew’s global breeding population, and the curlew is arguably the most pressing bird conservation challenge in the UK (Brown et al. 2015). However, the causes of wader declines likely include habitat loss, alteration and homogenisation (associated strongly with agricultural intensification), and predation by generalist predators (Brown et al. 2015, van der Wal & Palmer 2008, Ainsworth et al. 2016). There has been a concerted effort to reverse wader declines through habitat management, wader sensitive farming practices and predator control, all of which are likely to benefit waders at the local scale. However, the extent and severity of wader population declines means that large scale, landscape level, collaborative actions are needed if these trends are to be halted or reversed across much of these species’ current (and former) ranges. -

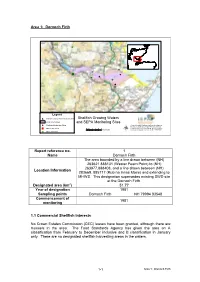

Area 1: Dornoch Firth Shellfish Growing Waters and SEPA Monitoring Sites Report Reference No. 1 Name Dornoch Firth Location

Area 1: Dornoch Firth ^_ ^_ ^_ ^_ ^_ ^_^_ ! ^_ # ^_ # ^_ ^_ Legend # Shellfish Growing Waters Monitoring Sites Shellfish Growing Waters Shellfish Growing Waters and SEPA Monitoring Sites ! Shellfish Production Sites (c) 2004 Scottish Environment Protection Agency. Includes material based upon Ordnance Survey " Marine Fish Farms 00.51 2 3 4 5 mapping with permission of H.M. Stationery Office. Kilometers (c) Crown Copyright. Licence number 100020538. ^_ Major Discharges µ Report reference no. 1 Name Dornoch Firth The area bounded by a line drawn between (NH) 263621 888131 (Wester Fearn Point) to (NH) 263977,888408, and a line drawn between (NH) Location Information 283669, 885717 (Rub na Innse Moire) and extending to MHWS. This designation supersedes existing SWD site at the Dornoch Firth. Designated area (km2) 51.77 Year of designation 1981 Sampling points Dornoch Firth NH 79994 83548 Commencement of 1981 monitoring 1.1 Commercial Shellfish Interests No Crown Estates Commission (CEC) leases have been granted, although there are mussels in the area. The Food Standards Agency has given the area an A classification from February to December inclusive and B classification in January only. There are no designated shellfish harvesting areas in the waters. 1- 1 Area 1: Dornoch Firth 1.2 Bathymetric Information This shellfish water encompasses almost the entire area of the Dornoch Firth. The area is some 22 km long by a maximum of 5.5 km wide. The maximum charted depth (at LAT) is <10 m. Approximately half of the area is <0 m chart depth, ie intertidal area exposed at low tide.