Site Condition Monitoring for Otters (Lutra Lutra) in 2011-12

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lands of Kincaid in Relation to the Highlands of Scotland

Peter Anthony Kincaid The lands of Kincaid in relation to the Highlands of Scotland. The physical boundary between the Lowlands and the Highlands of Scotland is the Highland boundary fault. The Highland boundary fault creates a visible change in the geology of the land. The fault comes ashore from the river Clyde near Helensburgh and continues in a north east direction towards Aberfoyle. It continues north east all the way to near Stonehaven on the coast of the North Sea.1 The islands of Inchmurrin, Creinch, Torrinch, and Inchcailloch in Loch Lomond all form visible parts of the Highland boundary Fault.2 The lands of Kincaid are at best about 15.3 English miles or about 24.6 kilometres from this fault (if one takes a direct line from the intersection of Campsie Road and Milton Road to summits north east of Conic Hill). Without doubt the lands of Kincaid are physically in Lowland Scotland. Some may argue that people may have considered a different boundary with regards to what one considered a Highlander. The evidence does not support this. It is not until the 1716 penal laws established against the Highlanders that this author could locate any official boundary. In what we refer to as the Disarming Act of 1716, the western bounds were established as "within the Shires of Dumbarton on the North-side of the Water of Leven, Stirling on the North-side of the River of Forth."3 At that time, Scots must have understood the Highlands to be north of the River Forth and north of the river Leven. -

Where to Go: Puffin Colonies in Ireland Over 15,000 Puffin Pairs Were Recorded in Ireland at the Time of the Last Census

Where to go: puffin colonies in Ireland Over 15,000 puffin pairs were recorded in Ireland at the time of the last census. We are interested in receiving your photos from ANY colony and the grid references for known puffin locations are given in the table. The largest and most accessible colonies here are Great Skellig and Great Saltee. Start Number Site Access for Pufferazzi Further information Grid of pairs Access possible for Puffarazzi, but Great Skellig V247607 4,000 worldheritageireland.ie/skellig-michael check local access arrangements Puffin Island - Kerry V336674 3,000 Access more difficult Boat trips available but landing not possible 1,522 Access possible for Puffarazzi, but Great Saltee X950970 salteeislands.info check local access arrangements Mayo Islands l550938 1,500 Access more difficult Illanmaster F930427 1,355 Access more difficult Access possible for Puffarazzi, but Cliffs of Moher, SPA R034913 1,075 check local access arrangements Stags of Broadhaven F840480 1,000 Access more difficult Tory Island and Bloody B878455 894 Access more difficult Foreland Kid Island F785435 370 Access more difficult Little Saltee - Wexford X968994 300 Access more difficult Inishvickillane V208917 170 Access more difficult Access possible for Puffarazzi, but Horn Head C005413 150 check local access arrangements Lambay Island O316514 87 Access more difficult Pig Island F880437 85 Access more difficult Inishturk Island L594748 80 Access more difficult Clare Island L652856 25 Access more difficult Beldog Harbour to Kid F785435 21 Access more difficult Island Mayo: North West F483156 7 Access more difficult Islands Ireland’s Eye O285414 4 Access more difficult Howth Head O299389 2 Access more difficult Wicklow Head T344925 1 Access more difficult Where to go: puffin colonies in Inner Hebrides Over 2,000 puffin pairs were recorded in the Inner Hebrides at the time of the last census. -

(Moine) Calc-Silicate Rocks Represent Metamorphosed Tuffs? a Geochemical Re-Appraisal Richard A

Do Neoproterozoic (Moine) calc-silicate rocks represent metamorphosed tuffs? A geochemical re-appraisal Richard A. Batchelor School of Earth & Environmental Sciences, University of St. Andrews, St. Andrews, Fife, Scotland KY16 9AL Running heads: LH: RICHARD A. BATCHELOR RH: DO NEOPROTEROZOIC (MOINE) CALC-SILICATE ROCKS REPRESENT METAMORPHOSED TUFFS? Suggest: CALC-SILICATE ROCKS 1 ABSTRACT: Following the identification of grey quartz–albite–chlorite–calcite–muscovite rocks in Meso- to Neo-proterozoic sequences in Scotland as metamorphosed tuffs of intermediate composition, it has been shown that this lithology will generate calc-silicate rocks at higher metamorphic grades. Both rock types occur as thin beds with sharp contacts with their host, occur as multiple beds in isolated suites, and share chemical compositions suggestive of volcanic sources with tholeiitic andesite affinities. The failure to recognise calc- silicate rocks as tuffs might explain the apparent scarcity of volcanogenic material through c. 220 million years of early Earth history in Scotland. KEYWORDS: Calc-silicates, tuffs, intermediate magmatism, Moine 2 1 Calc-silicate rocks, which are metamorphic rocks composed mostly of plagioclase feldspar, amphibole, 2 garnet, quartz and occasionally epidote, are sporadically distributed throughout the Neoproterozoic 3 Moine Supergroup of Scotland. The Moine Supergroup comprises a thick sequence of sedimentary 4 rocks, deposited in fluviatile (Bonsor & Prave 2008) and shallow marine environments between c. 950 5 Ma and 870 Ma (Mendum et al. 2009), intruded by some minor igneous intrusions, all of which were 6 subjected to regional metamorphism and deformation events (Strachan et al. 2010). The sediments 7 were derived from the denudation of the c.1000 Ma Grenville Orogen and deposited off the eastern 8 margin of Laurentia into a foreland basin. -

Ipas in Scotland • 2

IPAs in Scotland • 2 • 5 • 6 • 3 • 4 • 15 • 10 • 11 • 14 • 16 • 12 • 13 • 9 • 7 • 8 • 17 • 19 • 21 • 26 • 29 • 23 • 25 • 27 31 • • 33 • 18 • 28 • 32 • 24 • 20 • 22 • 30 • 40 • 34 • 39 • 41 • 45 • 35 • 37 • 38 • 44 • 36 • 43 • 42 • 47 • 46 2 Contents Contents • 1 4 Foreword 6 Scotland’s IPAs: facts and figures 12 Protection and management 13 Threats 14 Land use 17 Planning and land use 18 Land management 20 Rebuilding healthy ecosystems 21 Protected areas Code IPA name 22 Better targeting of 1 Shetland 25 Glen Coe and Mamores resources and support 2 Mainland Orkney 26 Ben Nevis and the 24 What’s next for 3 Harris and Lewis Grey Corries Scotland’s IPAs? 4 Ben Mor, Assunt/ 27 Rannoch Moor 26 The last word Ichnadamph 28 Breadalbane Mountains 5 North Coast of Scotland 29 Ben Alder and Cover – Glen Coe 6 Caithness and Sutherland Aonach Beag ©Laurie Campbell Peatlands 30 Crieff Woods 7 Uists 31 Dunkeld-Blairgowrie 8 South West Skye Lochs 9 Strathglass Complex 32 Milton Wood 10 Sgurr Mor 33 Den of Airlie 11 Ben Wyvis 34 Colonsay 12 Black Wood of Rannoch 35 Beinn Bheigier, Islay 13 Moniack Gorge 36 Isle of Arran 14 Rosemarkie to 37 Isle of Cumbrae Shandwick Coast 38 Bankhead Moss, Beith 15 Dornoch Firth and 39 Loch Lomond Woods Morrich More 40 Flanders Moss 16 Culbin Sands and Bar 41 Roslin Glen 17 Cairngorms 42 Clearburn Loch 18 Coll and Tiree 43 Lochs and Mires of the 19 Rum Ale and Ettrick Waters 20 Ardmeanach 44 South East Scotland 21 Eigg Basalt Outcrops 22 Mull Oakwoods 45 River Tweed 23 West Coast of Scotland 46 Carsegowan Moss 24 Isle of Lismore 47 Merrick Kells Citation Author Plantlife (2015) Dr Deborah Long with editorial Scotland’s Important comment from Ben McCarthy. -

Editor's Preface

EDITOR'S PREFACE 'Firthlands' embraces those eastern lowlands clustered around the Dor noch, Cromarty, Beauly and Inner Moray Firths. Firthlands of Ross and Sutherland focuses more particularly on the gentle and fertile country around the Dornoch and Cromarty Firths- from Golspie and Loch Fleet in the north, to Bonar Bridge, Tain and the Easter Ross peninsula, across to Cromarty and the Black Isle, and up-firth to Dingwall and Muir of Ord. Of the twelve contrasting chapters, one provides a broad geological background to the area and highlights landscape features as they have evolved through time- the Great Glen and Helmsdale Faults, glacially deepened and drowned river valleys, raised beaches, wave-formed shingle barriers. And it is the underlying geology that gave rise to the shape of early habitational and communications networks, to the Brora coal-mines and to the spa waters of Strathpeffer, to stone and sand and gravel and peat for extraction, to the nature and balance of agricultural practice, to the oil and gas fields off the coast. Such economic activity is most apparent for relatively recent times, so that six chapters concentrate on the seventeenth to early twentieth cen turies. Some explore trade and family links across to Moray and the Baltic, as well as with other parts of Scotland and beyond; others concentrate on changes in settlement patterns, agriculture and stock-rearing, both in the firthlands and their highland hinterland; yet others are more concerned with a particularly rich architectural heritage.In each case, there is a weave between Highlander and Lowlander, spiced with the ever-increasing exposure of the north to southern influences and pressures. -

Scottish Birds

ISSN 0036-9144 SCOTTISH BIRDS THE JOURNAL OF THE SCOTTISH ORNITHOLOGISTS' CLUB Vol. 10 No. 7 AUTUMN 1979 ORNITHOLIDAYS Member of The Association 1980 of British Travel Agents Holidays organised by Birdwatchers for Birdwatchers INDIA (North) INDIA (Assam) NOVA SCOTIA THE SEYCHELLES AUSTRIAN ALPS TANZANIA PORTUGAL MOROCCO CENTRAL WALES MALAWI ISLES OF SCILLY SRI LANKA ISLE OF MULL VANCOUVER & ROCKIES ISLE OF ISLAY THE GAMBIA THE CAIRNGORMS MAJORCA HEBRIDEAN CRUISES S.W. SPAIN DORSET GREECE SUFFOLK THE CAMARGUE FARNES & BASS ROCK LAKE NEUSIEDL YUGOSLAVIA Particulars sent on receipt of 8p stamp to : LAWRENCE G. HOLLOWAY ORNITHOLlDAYS (Regd) (WESSEX TRAVEL CENTRE) 1/3 VICTORIA DRIVE, BOGNOR REGIS, SUSSEX, England, P021 2PW Telephone 02433 21230 Telegrams : Ornitholidays Bognor Regis. ·000000000000000000000001 COLOUR SLIDES BINOCULAR We are now able to supply REPAIRS slides of most British Birds from our own collection, and from that of the R.S.P.B. CHARLES FRANK LID. Send 25p for sample slide are pleased to offer a special and our lists covering these concession to members of the Scot and birds of Africa-many tish Ornithologists' Club. Servicing fine studies and close-ups. and repairs of all makes of binocu lars will be undertaken at special FOR HIRE prices. Routine cleaning and re We have arranged to hire out aligning costs £5 + £1 post, packing slides of the R.S.P.B. These and insurance. Estimates will be are in sets of 25 at 60p in provided should additional work cluding postage & V.A.T. per be required. night's hire. Birds are group ed according to their natural Send to The Service Manager habitats. -

Surveys of Dogwhelks Nucella Lapillus in the Vicinity of Sullom Voe, Shetland, July 2015

Tí Cara, Point Lane, Cosheston, Pembrokeshire, SA72 4UN, UK Tel office +44 (0) 1646 687946 Mobile 07879 497004 E-mail: [email protected] Surveys of dogwhelks Nucella lapillus in the vicinity of Sullom Voe, Shetland, July 2015 A report for SOTEAG Prepared by: Jon Moore and Matt Gubbins Status: Final th Date of Release: 18 December 2015 Recommended citation: Moore, J.J. and Gubbins, M.J. (2015). Surveys of dogwhelks Nucella lapillus in the vicinity of Sullom Voe, Shetland, July 2015. A report to SOTEAG from Aquatic Survey & Monitoring Ltd., Cosheston, Pembrokeshire and Marine Scotland Science, Aberdeen. 42 pp +iv. Surveys of dogwhelks Nucella lapillus in the vicinity of Sullom Voe, Shetland, July 2015 Page i Acknowledgements Surveyors: Jon Moore, ASML, Cosheston, Pembrokeshire Christine Howson, ASML, Ormiston, East Lothian Dogwhelk imposex analysis: Melanie Harding & Matt Gubbins, Marine Scotland Science, Marine Laboratory, Aberdeen Other assistance and advice: Alex Thomson and colleagues at BP Pollution Response Base, Sella Ness; Tanja Betts, Louise Feehan & Craig Robinson, Marine Scotland Science, Marine Laboratory, Aberdeen Report review: Ginny Moore, Coastal Assessment, Liaison & Monitoring, Cosheston, Pembrokeshire Dr Mike Burrows and other members of the SOTEAG monitoring committee Data access This report and the data herein are the property of the Sullom Voe Association (SVA) Ltd. and its agent the Shetland Oil Terminal Environmental Advisory Group (SOTEAG) and are not to be cited without the written agreement of SOTEAG. SOTEAG/SVA Ltd. will not be held liable for any losses incurred by any third party arising from their use of these data. © SOTEAG/SVA Ltd. 2015 Aquatic Survey & Monitoring Ltd. -

Systematic List for 1994 Tristart Ap Rheiriallt 6 Little Ringed Plover on Islay, 16 May 1983 - the Sole Argyll Record J.C.B

The Eleventh ARGYLL BIRD REPORT with Systematic List for the year 1994 . Edited by J.C.A. Craik Assisted by T. ap Rheinallt Systematic List by T. ap Rheinallt Cover picture by L. J. Craik Published by the Argyll Bird Club (Recognised by the Inland Revenue as a charity) October 1995 (Copyright, Argyll Bird Club) 1 Argyll Bird Club The Argyll Bird Club was formed in 1985 and aims to play an active role in the promotion of ornithology and conservation in Argyll, in the District of Argyll and Bute, and in Strathclyde Region. The club has steadily built up its membership to the present level of around 170. One day-long meeting is held in the spring and another in the autumn. These include talks, scientific papers and field trips. Conferences on selected topics are also organised ociasionaliy. In 1986,the club held its first conference, a successful meeting between foresters and bird conservationists. This was followed, in 1987, by a memorable two-day conference in Oban on fish farming and the environment. The club has close contacts with other conservation groups, both locally and nationally, including the British Trust for Ornithology, the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, the Scottish Ornithologists’Club and the Scottish Wildlife Trust. The club promotes a greater interest in birds by participation in various recording schemes. Members receive four newsletters a year as well as the annual Argyll Bird Report. The report is distributed free to all members (one per family membership) and is the major publication of the club. Much of the annual subscription is used to pay for the report and newsletters. -

Scottish Nature Omnibus Survey August 2019

Scottish Natural Heritage Scottish Nature Omnibus Survey August 2019 The general public’s perceptions of Scotland’s National Nature Reserves Published: December 2019 People and Places Scottish Natural Heritage Great Glen House Leachkin Road Inverness IV3 8NW For further information please contact [email protected] 1. Introduction The Scottish Nature Omnibus (SNO) is a survey of the adult population in Scotland which now runs on a biennial basis. It was first commissioned by SNH in 2009 to measure the extent to which the general public is engaged with SNH and its work. Seventeen separate waves of research have been undertaken since 2009, each one based on interviews with a representative sample of around 1,000 adults living in Scotland; interviews with a booster sample of around 100 adults from ethnic minority groups are also undertaken in each survey wave to enable us to report separately on this audience. The SNO includes a number of questions about the public’s awareness of and visits to National Nature Reserves (see Appendix). This paper summarises the most recent findings from these questions (August 2019), presenting them alongside the findings from previous waves of research. Please note that between 2009 and 2015 the SNO was undertaken using a face to face interview methodology. In 2017, the survey switched to an on-line interview methodology, with respondents sourced from members of the public who had agreed to be part of a survey panel. While the respondent profile and most question wording remained the same, it should be borne in mind when comparing the 2017 and 2019 findings with data from previous years that there may be differences in behaviour between people responding to a face to face survey and those taking part in an online survey that can impact on results. -

NORTH of SCOTLAND COLLEGE of AGRICULTURE School of Agriculture, Aberdeen Agricultural Economics Department (

NORTH OF SCOTLAND COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE School of Agriculture, Aberdeen Agricultural Economics Department ( G1ANNINT NDATTOM OF AC.7 ICIGVILTU LI JUL 12.3 Farm Crop Irrigation in the North of Scotland 1964 and 1965 by J. S. Bon;, M.Sc. June, 1966 Economic Retort No. 117 Price 31- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Agricultural Economics Department of the North of Scotland College of Agriculture wishes to thank those farmers and members of the County Advisory Staff who supplied the records and information on which this report is based. THE NORTH OF SCOTLAND CO D E OF AGRICULTURE AGRICULTURAL ECONavlICS DEPARTMENT FARM CROP IRRIGATION IN THE NORTH OF SCOTLAND 1964. arrl 1965 by J. S. Bone. ivl.Sc, June, 1966. FARM CROP IRRIGATION IN THE NORTH OP. SCOTLAND 1964. AND 1965 CONTENTS Pape INTRCIDUCTION Weather During Survey Period. 1964. and 1965 • The Sa41.e 10 STJRVEY RESULTS 13 Water Sources 13 Equipment 15 Utilisation of Equipment 1964. and. 1965 17 IRRIGATION COSTS AND RETURNS - IN THE NORTH 'OF SCOTLAND 19 &LEARY AND CONCLUSIONS 26 APPENDICES Appendix I - River Purification Board. Areas, North of Scotland. College of Agriculture Mainland. Area. 29 Appendix II - Acreage of HOrticultural Crops at June.,- 1964., North of Scotland. College of Agriculture Area, 30 Appendix III - Total Acreage of Agricultural Crops at June,"1964., North of Scotland. College of Agriculture Area. 31 Appendix IV - Glossary of Terms-Used. 32 BIBLICGRA.PHY 33 • LIST OF TABLES Table Page 1 Frequency of Irrigation Need - Inverness (Dalcross) Area, April-September 4. 2 Frequency of Irrigation Need. - Inverness (Dalcross) Area, April-July 3 Irrigation Sets in the North of Scotland. -

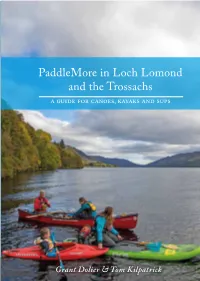

Paddlemore in Loch Lomond and the Trossachs a Guide for Canoes, Kayaks and Sups Paddlemore in Loch Lomond and the Trossachs a Guide for Canoes, Kayaks and Sups

PaddleMore in LochTrossachs PaddleMore Lomond and the PaddleMore in Loch Lomond and the Trossachs a guide for canoes, kayaks and sups PaddleMore in Loch Lomond and the Trossachs a guide for canoes, kayaks and sups Whether you want hardcore white water, multi-day touring Kilpatrick Tom & Dolier Grant trips or a relaxing afternoon exploring sheltered water with your family, you’ll find all that and much more in this book. Loch Lomond & The Trossachs National Park is long estab- lished as a playground for paddlers and attracts visitors from all over the world. Loch Lomond itself has over eighty kilometres of shoreline to explore, but there is so much more to the park. The twenty-two navigable lochs range from the vast sea lochs around Loch Long to small inland Loch Lomond bodies such as Loch Chon. & the Trossachs The rivers vary from relaxed meandering waterways like the Balvaig to the steep white water of the River Falloch and 9 781906 095765 everything in between. Cover – Family fun on Loch Earn | PaddleMore Back cover – Chatting to the locals, River Balvaig | PaddleMore Grant Dolier & Tom Kilpatrick Loch an Daimh Loch Tulla Loch Also available from Pesda Press Bridge of Orchy Lyon Loch Etive Loch Tay Killin 21b Tyndrum River Dochart River Loch 21a Fillan Iubhair Loch Awe 20 LOCH LOMOND & Crianlarich Loch Lochearnhead Dochart THE TROSSACHS 19 Loch NATIONAL PARK Earn Loch 5 River Doine 17 River Falloch Loch 32 Voil Balvaig 23 Ardlui 18 Loch Loch Sloy Lubnaig Loch Loch Katrine Arklet 12 Glen Finglas Garbh 3 10 Reservoir Uisge 22 Callander -

Surveys of Dogwhelks Nucella Lapillus in the Vicinity of Sullom Voe, Shetland, July 2013

Tí Cara, Point Lane, Cosheston, Pembrokeshire, SA72 4UN, UK Tel office +44 (0) 1646 687946 Mobile 07879 497004 E-mail: [email protected] Surveys of dogwhelks Nucella lapillus in the vicinity of Sullom Voe, Shetland, July 2013 A report for SOTEAG Prepared by: Jon Moore and Matt Gubbins Status: Final th Date of Release: 14 February 2014 Recommended citation: Moore, J.J. and Gubbins, M.J. (2014). Surveys of dogwhelks Nucella lapillus in the vicinity of Sullom Voe, Shetland, July 2013. A report to SOTEAG from Aquatic Survey & Monitoring Ltd., Cosheston, Pembrokeshire and Marine Scotland Science, Aberdeen. 42 pp +iv. Surveys of dogwhelks Nucella lapillus in the vicinity of Sullom Voe, Shetland, July 2013 Page i Acknowledgements Surveyors: Jon Moore, ASML, Cosheston, Pembrokeshire Christine Howson, ASML, Ormiston, East Lothian Dogwhelk imposex analysis: Matthew Gubbins, Marine Scotland Science, Marine Laboratory, Aberdeen Other assistance and advice: Alex Thomson and colleagues at BP Pollution Response Base, Sella Ness; Tanja Betts, Louise Feehan and Kelly MacNeish, Marine Scotland Science, Marine Laboratory, Aberdeen Report review: Ginny Moore, Coastal Assessment, Liaison & Monitoring, Cosheston, Pembrokeshire Matthew Gubbins, Marine Scotland Science, Marine Laboratory, Aberdeen Dr Mike Burrows and other members of the SOTEAG monitoring committee Data access This report and the data herein are the property of the Sullom Voe Association (SVA) Ltd. and its agent the Shetland Oil Terminal Environmental Advisory Group (SOTEAG) and are not to be cited without the written agreement of SOTEAG. SOTEAG/SVA Ltd. will not be held liable for any losses incurred by any third party arising from their use of these data.