"Find Direction Out" : in the Archives of Hamlet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of Stanislavsky and the Moscow Art Theatre's 1923 And

CULTURAL EXCHANGE: THE ROLE OF STANISLAVSKY AND THE MOSCOW ART THEATRE’S 1923 AND1924 AMERICAN TOURS Cassandra M. Brooks, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2014 APPROVED: Olga Velikanova, Major Professor Richard Golden, Committee Member Guy Chet, Committee Member Richard B. McCaslin, Chair of the Department of History Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Brooks, Cassandra M. Cultural Exchange: The Role of Stanislavsky and the Moscow Art Theatre’s 1923 and 1924 American Tours. Master of Arts (History), August 2014, 105 pp., bibliography, 43 titles. The following is a historical analysis on the Moscow Art Theatre’s (MAT) tours to the United States in 1923 and 1924, and the developments and changes that occurred in Russian and American theatre cultures as a result of those visits. Konstantin Stanislavsky, the MAT’s co-founder and director, developed the System as a new tool used to help train actors—it provided techniques employed to develop their craft and get into character. This would drastically change modern acting in Russia, the United States and throughout the world. The MAT’s first (January 2, 1923 – June 7, 1923) and second (November 23, 1923 – May 24, 1924) tours provided a vehicle for the transmission of the System. In addition, the tour itself impacted the culture of the countries involved. Thus far, the implications of the 1923 and 1924 tours have been ignored by the historians, and have mostly been briefly discussed by the theatre professionals. This thesis fills the gap in historical knowledge. -

A Conversation About Costume with Edward Gordon Craig, Léon Bakst, and Pablo Picasso Annie Holt Independent Scholar

Mime Journal Volume 26 Action, Scene, and Voice: 21st-Century Article 8 Dialogues with Edward Gordon Craig 2-28-2017 Speaking Looks: A Conversation About Costume With Edward Gordon Craig, Léon Bakst, And Pablo Picasso Annie Holt independent scholar Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/mimejournal Part of the Dance Commons, Other Theatre and Performance Studies Commons, and the Theatre History Commons Recommended Citation Holt, Annie (2017) "Speaking Looks: A Conversation About Costume With Edward Gordon Craig, Léon Bakst, And Pablo Picasso," Mime Journal: Vol. 26, Article 8. DOI: 10.5642/mimejournal.20172601.08 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/mimejournal/vol26/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mime Journal by an authorized editor of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ACTION, SCENE, AND VOICE: 21ST-CENTURY DIALOGUES WITH EDWARD GORDON CRAIG 46 scholarship.claremont.edu/mimejournal • Mime Journal February 2017. pp. 46–60. ISSN 2327–5650 online Speaking Looks: A Conversation about Costume with Edward Gordon Craig, Léon Bakst, and Pablo Picasso Annie Holt Edward Gordon Craig perceived a vast difference between his design work and the design of the famous Ballets Russeshe called the Ballets Russes designs “unimportant” and “trash.”1 Many early theater historians followed Craig’s lead in framing them as opposing schools of scenography, focusing on their differences in dimensionality. The Ballets Russes designers, made up almost exclusively of painters, are often considered “the gorgeous sunset of scene-painting” in the two-dimensional baroque tradition, typified by the painted canvas backdrop, whereas Craig’s “artist of the theatre” innovatively used three- dimensional objects such as architectural columns or stairs (Laver, “Continental Designers,” 20). -

Gordon Craig's Production of "Hamlet" at the Moscow Art Theatre Author(S): Kaoru Osanai and Andrew T

Gordon Craig's Production of "Hamlet" at the Moscow Art Theatre Author(s): Kaoru Osanai and Andrew T. Tsubaki Reviewed work(s): Source: Educational Theatre Journal, Vol. 20, No. 4 (Dec., 1968), pp. 586-593 Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3205002 . Accessed: 01/02/2013 18:58 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Johns Hopkins University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Educational Theatre Journal. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded on Fri, 1 Feb 2013 18:58:37 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions THEATRE KAORU OSANAI ARRHIVES Gordon Craig's Production of Hamlet at the Moscowz Art Theatre Translated with an Introduction by ANDREW T. TSUBAKI The Hamlet production at the Moscow Art Theatre staged by Edward Gordon Craig and Konstantin Sergeivich Stanislavsky was without doubt one of the major works Craig left to us, and moreover was an important production in the history of modern theatre. Despite its significance, no substantial description of the production is available in English. A memoir prepared by Kaoru Osanai (i881-1928) fills this vital gap, providing helpful details which are much needed. -

THE THEATRE the Russian Theatre Represents Various Forms of the Western Theatre with Something of Its Own Besides

CHAPTER VIII THE THEATRE THE Russian theatre represents various forms of the Western theatre with something of its own besides. The conventional theatre and the progressive theatre, crude The Theatre. melodrama and the finest symbolism are all here. There is dull aping of Western fashions, and there is also an extraordinary acute sense of the theatre as a problem. The problem is stated and faced with characteristic Russian frankness and thoroughness. The remotest possibilities of dramatic art are taken into con- sideration, including the possibility that the theatre in its present form may have outlived its time and Should be superseded. Western plays and players quickly find their way to Russia and, indeed, translated plays constitute the bull< of the Russian theatrical rkpertoire. All kinds of Western innovations are eagerly discussed and readily adopted, and at the same time in various odd corners in the capitals stale and obsolete theatrical forms stubbornly hold their own. Both the best and the worst sides of the theatre are to be found in Russia. The dullness and shallowness of theatrical routine are most obviously and oppressingly dull and shallow. But over against this is the openness of mind, the keenness of intelligence, the energy and persistence in inquiry and experiment that place the Russian theatre in the vanguard of the modern theatrical movement. And the progressive spirit is steadily gaining ground ; theatrical conventionalism is losing its self-confidence, is beginning to doubt of itself. There are no fixed new standards, except that things must be done as well and intelligently as possible, and the old standards are drifting into oblivion. -

From Fact to Farce

FROM FACT TO FARCE THE REALITY BEHIND BULGAKOV’S BLACK SNOW A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Erin K Kahoa December, 2015 FROM FACT TO FARCE THE REALITY BEHIND BULGAKOV’S BLACK SNOW Erin K Kahoa Thesis Approved: Accepted: _______________________________ _______________________________ Advisor School Director Mr. James Slowiak Dr. John Thomas Dukes _______________________________ _______________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the College Mr. Adel Migid Dr. Chand Midha _______________________________ _______________________________ Committee Member Dean of the Graduate School Mr. Durand Pope Dr. Chand Midha _______________________________ Date ii DEDICATION To Kate, who knew who Bulgakov was before I got the chance to hurl my knowledge at her. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work would not exist without my Advisor, James Slowiak, members of my committee, Durand Pope and Dr. Don “Doc” Williams, my faculty reader, Adel Migid, and those I tirelessly harangued for edits and revisions: Dr. Steven Hardy, Linda L Kahoa, Becky McKnight and Emily Sutherlin. Also, a special thank you to Mikhail Bulgakov for being so dang interesting. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I. PURPOSE AND METHODS OF RESEARCH ...............................................................1 II. THE HISTORY OF THE MOSCOW ART THEATRE .................................................4 III. THE LIFE OF BULGAKOV .......................................................................................20 -

Creating the Title Role in Moliere's the Misanthrope

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses Spring 5-13-2016 How to be a Misanthrope: Creating the Title Role in Moliere’s The Misanthrope David Cleveland Brown University of New Orleans, New Orleans, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Part of the Acting Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, Other Theatre and Performance Studies Commons, and the Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Brown, David Cleveland, "How to be a Misanthrope: Creating the Title Role in Moliere’s The Misanthrope" (2016). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 2128. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/2128 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. How to be a Misanthrope: Creating the Title Role in Moliere’s The Misanthrope A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Film and Theatre Performance by David Brown B.A. -

Three Sisters Anton Chekhov Pdf

Three sisters anton chekhov pdf Continue For the musical written by Oscar Hammerstein II and Jerome Kern, see Three Sisters (musical). Trish is redirecting here. For the Czech punk rock band, see Tři forests. For opera by Péter Eötvös, see Tri forestry (opera). Three SistersCover of first edition, published in 1901 by Adolf MarksWritten by Anton TchekhovCharactersProzorov family: Olga romanized: Tri forestry) is a work by the Russian writer and ,'لри сeстрل :Sergeyevna Prozorova Maria Sergeyevna Kulygina Irina Sergeyevna Prozorova Andrei Sergeyevich Prozorov Date premiered 1901 (1901), MoscowOxin language RussianGenreDramaSettingA provincial Russian garrison city Chekhov in a 1905 illustration. Three Sisters (Russian playwright Anton Tchekhov. It was written in 1900 and first presented in 1901 at the Moscow Art Theatre. The work is sometimes included in Chekhov's short list of outstanding works, along with Cherry Orchard, The Seagull and Uncle Vanya. [1] Characters Prozorovs Olga Sergeyevna Prozorova (Olga) - The larger of the three sisters, is the matriarchal figure of the Prozorov family, although at the beginning of the work she is only 28 years old. Olga is a high school teacher, where she often fills in as principal whenever the principal is absent. Olga is a spinster and at one point tells Irina that she would marry any man, even an old man if he had asked her. Olga is very maternal even in the elderly servants, holding the elderly nurse/detainee Anfisa, long after she has ceased to be useful. When Olga reluctantly takes on the role of director permanently, she takes anfisa with her to escape the clutches of heartless Natasha. -

Notes and References

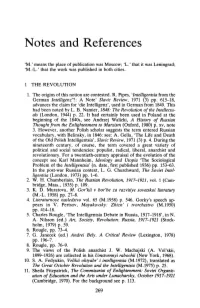

Notes and References 'M.' means the place of publication was Moscow; 'L.' that it was Leningrad; 'M.-L.' that the work was published in both cities. 1 THE REVOLUTION 1. The origins of this notion are contested. R. Pipes, 'Intelligentsia from the German Intelligenz'?: A Note' Slavic Review, 1971 (3) pp. 615-18, advances the claim for 'die Intelligenz', used in German from 1849. This had been noted by L. B. Namier, 1848: The Revolution of the Intellectu als (London, 1944) p. 22. It had certainly been used in Poland at the beginning of the 1840s, see Andrzej Walicki, A History of Russian Thought from the Enlightenment to Marxism (Oxford, 1980) p. xv, note 3. However, another Polish scholar suggests the term entered Russian vocabulary, with Belinsky, in 1846: see: A. Gella, 'The Life and Death of the Old Polish Intelligentsia', Slavic Review, 1971 (3) p. 4. During the nineteenth century, of course, the term covered a great variety of political and social tendencies: populist, radical, liberal, anarchist and revolutionary. For a twentieth-century appraisal of the evolution of the concept see Karl Mannheim, Ideology and Utopia 'The Sociological Problem of the Intelligentsia' (n. date, first published 1936) pp. 153--63. In the post-war Russian context, L. G. Churchward, The Soviet Intel ligentsia (London, 1973) pp. 1--6. 2. W. H. Chamberlain, The Russian Revolution, 1917-1921, vol. 1 (Cam bridge, Mass., 1935) p. 109. 3. K. D. Muratova, M. Gor'kii v bor'be za razvitiye sovetskoi literatury (M.-L. 1958) pp. 27-8. 4. Literaturnoye nasledstvo vol. -

The Cherry Orchard

2016 BAM Winter/Spring #TheCherryOrchard Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board Katy Clark, President Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer The Cherry Orchard BAM Harvey Theater Feb 17—20, 23—27 at 7:30pm; Feb 21 at 3pm Running time: approx. three hours including intermission By Anton Chekhov Maly Drama Theatre of St. Petersburg, Russia Directed and adapted by Lev Dodin Design by Aleksander Borovsky Lighting design by Damir Ismagilov Season Sponsor: Renova Group is the major sponsor of The Cherry Orchard. Support provided by Trust for Mutual Understanding. Major support for theater at BAM provided by: The Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation The Francena T. Harrison Foundation Trust Donald R. Mullen Jr. The Fan Fox & Leslie R. Samuels Foundation, Inc. The Morris and Alma Schapiro Fund The SHS Foundation The Shubert Foundation, Inc. #TheCherryOrchard DANNA ABYZOVA ELIZAVETA BOIARSKAIA IGOR CHERNEVICH ANDREI KONDRATIEV DANILA KOZLOVSKIY SERGEI KURYSHEV STANISLAV NIKOLSKII KSENIA RAPPOPORT OLEG RYAZANTSEV TATIANA SHESTAKOVA SERGEI VLASOV ARINA VON RIBBEN #TheCherryOrchard CAST Lyubov Ranevskaya, a landowner Ksenia Rappoport Anya, her daughter Danna Abyzova Varya, her adopted daughter Elizaveta Boiarskaia Leonid Gayev, her brother Igor Chernevich, Sergei Vlasov (alternating) Yermolai Lopakhin, a merchant Danila Kozlovskiy Petr Trofimov, a student Oleg Ryazantsev Charlotta, a governess Tatiana Shestakova Semen Yepikhodov, a clerk Andrei Kondratiev Dunyasha, a housemaid Arina Von Ribben Firs, a manservant Sergei Kuryshev Yasha, young manservant Stanislav Nikolskii ADDITIONAL CREDITS Camera man Alisher Hamidhodgaev Music by Gilles Thibaut, Paul Misraki, Johann Strauss Technical manager Alexander Pulinets Stage manager Natalia Sollogub Musical coordination Mikhail Alexandrov Pianists Ksenia Vasilieva, Elena Lapina Artistic collaboration Valery Galendeev Artistic coordinator Dina Dodina Thanks to Francine Yorke, London, for the titles. -

Theatre and Performance Studies at the Moscow Art Theatre June 1

Theatre and Performance Studies at the Moscow Art Theatre Moscow, Russia June 1 - 30, 2020 This study abroad program is coordinated by the NIU Study Abroad Office (SAO), in cooperation with the NIU School of Theatre and Dance and the Moscow Art Theatre, Moscow, Russia. The NIU Moscow Art Theatre offers students a living experience with one of the most accomplished and groundbreaking theaters in the world. The founders of the Moscow Art Theatre created a new form of drama, believing that all theater must reflect and illuminate the human condition. Stanislavsky and Nemirovich-Danchenko, primarily through their association with the works of Anton Chekhov, maintained that the crucial element in the art of theater is ensemble. They created a company where actors, directors, writers, and designers have been making theater together for years, sometimes lifetimes. The approach to theater in Russia is very different from most of what is experienced in the United States. Because it is seen as an expression of the Russian identity, theater holds an exalted place in the culture. The NIU Moscow Art Theatre offers young theater artists the unique opportunity to engage in this demanding and highly rewarding artistic environment. ANTICIPATED DATES: The program will officially begin on June 1, 2020 in Moscow and will end on June 30, 2020. Students are expected to coordinate their own travel arrangements in order to arrive in Moscow on June 1, 2020. Arrival and departure dates will be confirmed at a later date will be made through a consolidator organized by the director of the program. PROGRAM OVERVIEW: This is the s17th offering in an institutional relationship between the Northern Illinois University School of Theatre and Dance and the Moscow Art Theatre (MXAT). -

The Shadow Puppets of Elsinore: Edward Gordon Craig and the Cranach Press Hamlet James P

Mime Journal Volume 26 Action, Scene, and Voice: 21st-Century Article 9 Dialogues with Edward Gordon Craig 2-28-2017 The hS adow Puppets of Elsinore: Edward Gordon Craig and the Cranach Press Hamlet James P. Taylor Pomona College Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/mimejournal Part of the Acting Commons, Book and Paper Commons, Dramatic Literature, Criticism and Theory Commons, Fine Arts Commons, Illustration Commons, Literature in English, British Isles Commons, Other German Language and Literature Commons, Performance Studies Commons, Printmaking Commons, and the Theatre History Commons Recommended Citation Taylor, James P. (2017) "The hS adow Puppets of Elsinore: Edward Gordon Craig and the Cranach Press Hamlet," Mime Journal: Vol. 26, Article 9. DOI: 10.5642/mimejournal.20172601.09 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/mimejournal/vol26/iss1/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mime Journal by an authorized editor of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ACTION, SCENE, AND VOICE: 21ST-CENTURY DIALOGUES WITH EDWARD GORDON CRAIG 61 scholarship.claremont.edu/mimejournal • Mime Journal February 2017. pp. 61–77. ISSN 2327–5650 online The Shadow Puppets of Elsinore: Edward Gordon Craig and the Cranach Press Hamlet James P. Taylor “To save the Theatre, the Theatre must be destroyed, the Actors and Actresses must all die of the plague … They make Art impossible.” (Eleonora Duse, quoted in Symons 336) This provocative statement by the acclaimed late nineteenth and early twentieth century Italian actress Eleonora Duse is the epigraph for one of the most controversial theories of the modern European theater. -

(1860-1904) Chekhov & Stanislavski

Anton Chekhov (1860-1904) Born the son of an abusive clerk (and later grocer) and grandson to a liberated serf, Anton Pavlovich Chekhov is regarded by many as one of the greatest writers of short stories in the history of the style. In the theatre he is highly regarded for his only four plays and his work with the Moscow Art Theatre (MXAT), specifically his collaboration with director Konstantin Stanislavski. His writing began out of necessity to provide for himself and his family in Moscow where his father had fled to avoid debtors’ prison. In order to provide for the family as well as pay his tuition to medical school, he began to submit daily humorous, short stories to publishers. Although his fame comes from his writing, he always considered his work as a physician his primary career. Ironically (for a physician), Chekhov found himself wrestling constantly with tuberculosis from 1884 onwards. He was not officially diagnosed until 1897, when he suffered a hemorrhage in his lungs that resulted in a necessary change in lifestyle, prompting his move to the countryside town of Yalta. Anton’s brother Ivan worked as a school teacher and tutor in Voskressensk, outside of Moscow. Each year the Chekhov family would spend their summer in the village with Ivan. A military battery, led by the Colonel B.I. Mayevsky was also stationed in Voskressensk at the time. Anton became close friends with the Colonel and his family, and it was from his time in the small town that he gained the military and rural-life inspiration for Three Sisters.