Physicochemical Properties of C-Type Starch from Root Tuber of Apios Fortunei in Comparison with Maize, Potato, and Pea Starches

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Add a Tuber to the Pod: on Edible Tuberous Legumes

LEGUME PERSPECTIVES Add a tuber to the pod: on edible tuberous legumes The journal of the International Legume Society Issue 19 • November 2020 IMPRESSUM ISSN Publishing Director 2340-1559 (electronic issue) Diego Rubiales CSIC, Institute for Sustainable Agriculture Quarterly publication Córdoba, Spain January, April, July and October [email protected] (additional issues possible) Editor-in-Chief Published by M. Carlota Vaz Patto International Legume Society (ILS) Instituto de Tecnologia Química e Biológica António Xavier Co-published by (Universidade Nova de Lisboa) CSIC, Institute for Sustainable Agriculture, Córdoba, Spain Oeiras, Portugal Instituto de Tecnologia Química e Biológica António Xavier [email protected] (Universidade Nova de Lisboa), Oeiras, Portugal Technical Editor Office and subscriptions José Ricardo Parreira Salvado CSIC, Institute for Sustainable Agriculture Instituto de Tecnologia Química e Biológica António Xavier International Legume Society (Universidade Nova de Lisboa) Apdo. 4084, 14080 Córdoba, Spain Oeiras, Portugal Phone: +34957499215 • Fax: +34957499252 [email protected] [email protected] Legume Perspectives Design Front cover: Aleksandar Mikić Ahipa (Pachyrhizus ahipa) plant at harvest, [email protected] showing pods and tubers. Photo courtesy E.O. Leidi. Assistant Editors Svetlana Vujic Ramakrishnan Nair University of Novi Sad, Faculty of Agriculture, Novi Sad, Serbia AVRDC - The World Vegetable Center, Shanhua, Taiwan Vuk Đorđević Ana María Planchuelo-Ravelo Institute of Field and Vegetable Crops, Novi Sad, Serbia National University of Córdoba, CREAN, Córdoba, Argentina Bernadette Julier Diego Rubiales Institut national de la recherche agronomique, Lusignan, France CSIC, Institute for Sustainable Agriculture, Córdoba, Spain Kevin McPhee Petr Smýkal North Dakota State University, Fargo, USA Palacký University in Olomouc, Faculty of Science, Department of Botany, Fred Muehlbauer Olomouc, Czech Republic USDA, ARS, Washington State University, Pullman, USA Frederick L. -

Sabal Minor Is On-Line At

abal minor A bimonthly newsletter for the members of VOLUME 10, NUMBER 4 S August - September 2007 T HE FLORIDA NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY August President’s Message Shorebirds and blue-winged teal arrive to winter on Florida wetlands and This has been an exciting several months. We had an absolutely fabulous lakes. Yellow warbler migration begins. conference. Our membership is up, with an unprecedented jump in the past year. Short-tailed shrews are beginning a We have our first officer from north Florida in many years (Ann Redmond, from second round of breeding for the year. the Magnolia Chapter, Tallahassee). We just signed a two year contract with Karina Deer are breeding in southern Florida. Veaudry, so she’s now contracted as our Executive Director again. And we have Gopher tortoises are hatching. Bass two new chapters: Pine Lily (Osceola County) and Sweet Bay (Jackson County). are foraging in shallows in early morning, Karina and I spent a very long weekend doing something I’ve longed to do — late evenings and nighttime. scanning old minutes. We spent nearly eight hours scanning and making PDF files A few blooms to watch for: goat’s of the notes from 1982 to 1996, and I spent nearly 12 hours more reading them and rue, Tephrosia virginiana; cranefly uploading them to the Forum. The reading was incredibly interesting. We even orchid, Tipularia discolor; various found approved policies that we’d long forgotten that we had (especially one on elephantsfoot, such as Elephantopus invasive species). We also found the origins of many standing procedures whose carolinianus and E. -

"Response of Apios Americana to Nitrogen and Inoculation"

HORTSCIENCE 26(7):853-855. 1991. Response of Apios americana to Nitrogen and Inoculation D.H. Putnam1, G.H. Heichel2, and L.A. Field3 Department of Agronomy and Plant Genetics, 411 Borlaug Hall, University of Minnesota, St. Paul, MN 55108 Additional index words groundnut, potato bean, new crops, Bradyrhizobium japonicum, tuber yield, legume symbiosis, nitrogen fertilizers Abstract. Apios americana Medikus (apios) is a wild tuberous legume with potential as a crop plant. Five apios accessions were grown in sand culture in two greenhouse experiments to examine the effect of N fertilization and inoculation with Bradyrhizobium japonicum on yield and plant characteristics. A common soybean B. japonicum strain (USDA76) was applied to plants watered with 0, 50, 100, 200, or 300 ppm N solutions (NH4NO3), plus a complete nutrient solution. At 0 N, total dry matter yield of nonin- oculated plants was only » 30% of inoculated plants. However, total dry-matter yields of inoculated plants at 0 N were only »77% of plants supplemented with 50 or 100 ppm, indicating that inoculation alone was insufficient to meet the N needs of the plant. Tuber weight was increased by both N and inoculation, but tuber weight decreased at N concentrations >100 ppm. Differences among plant accessions with regard to tuber fresh weight, harvest index, and modulation were found. These studies indicated that N fertilization maybe required to maximize tuber yields of apios. Apios americana (groundnut or apios) is its unique role as an N2-fixing and tuber- a wild legume native to the eastern half of producing plant (Putnam et al., 1990). -

Taro Systematik Unterklasse: Froschlöffelähnliche (Alismatidae

Taro Taro (Colocasia esculenta) Systematik Unterklasse: Froschlöffelähnliche (Alismatidae) Ordnung: Froschlöffelartige (Alismatales) Familie: Aronstabgewächse (Araceae) Unterfamilie: Aroideae Gattung: Colocasia Art: Taro Wissenschaftlicher Name Colocasia esculenta (L.) Schott Traditioneller Taroanbau auf Terrassen aus Lavagestein auf der Insel Kauaʻi Taro (Colocasia esculenta) ist eine Nutzpflanze aus der Familie der Aronstabgewächse (Araceae), die seit mehr als 2000 Jahren als Nahrungspflanze kultiviert wird. Ein anderer Name für Taro ist Wasserbrotwurzel. In alten Nachschlagewerken, wie z. B. Pierer's Universal-Lexikon findet sich für die Pflanze auch die Bezeichnung Tarro. Genutzt werden vorwiegend die stärkehaltigen Rhizome der Pflanze. Sie werden wie Kartoffeln gekocht. In den Anbauländern werden auch die Blätter und Blattstiele als Gemüse gegessen. Sie enthalten viel Mineralien, Vitamin A, B und C. Taro wird heute weltweit in feuchten, tropischen und subtropischen Klimazonen angebaut. Für den Export wird er in Ägypten, Costa Rica, der Karibik, Brasilien und Indien angepflanzt. In Hawaii ist die dort kalo[1] genannte Pflanze eine der wichtigsten traditionellen Nutzpflanzen. Aus den Rhizomen wird poi, eine Paste, hergestellt. Die Aborigines in Australien nutzen diese Pflanze um daraus Busch-Brot zu backen, indem sie aus dem Rhizom Mehl herstellten. Siehe auch [Bearbeiten] Sumpfpflanzen Wasserpflanzen Weblinks [Bearbeiten] Rhizome der Taro Commons: Taro – Album mit Bildern, Videos und Audiodateien Taro – eine Nahrungs- und eine Giftpflanze Beschreibung und Verwendungsmöglichkeit Einzelnachweise [Bearbeiten] 1. ↑ taro, kalo in Hawaiian Dictionaries Von „http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taro― Kategorien: Aronstabgewächse | Nutzpflanze | Blattgemüse | Wurzelgemüse Taro From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search This article is about the plant. For other uses, see Taro (disambiguation). It has been suggested that this article or section be merged with Colocasia esculenta. -

Apios Americana Medik

Apios americana Medik. Common Names: Groundnut, Wild Bean, Potato-bean, American Potato Bean, Indian-potato (1, 4, 7). Etymology: Apios is Greek for “pear”; the plant was named such because of its pear-shaped tubers. Americana means “American” (3, 7, 17). Botanical synonyms: Apios tuberosa (4), Glycine apios (14). FAMILY: Fabaceae (the Pea family). Fabaceae is also known as Leguminosae Quick Notable Features: ¬ Purple-brown flowers in axillary racemes ¬ Papilionaceous (butterfly-like) corolla ¬ Stem and leaves are unarmed ¬ Pinnately compound leaves with 5-7 ovate to lanceolate leaflets per leaf, each leaflet with a round (not C- shaped) petiolule Plant Height: Climbing individuals grow up to 5m long (4). Subspecies/varieties recognized (11): Apios americana f. cleistogama Fernald Apios americana f. pilosa Steyerm. Apios americana f. keihneri Oswald Apios americana var. turrigera Fernald Apios americana f. mcculloughii Oswald Most Likely Confused with: Apios priceana, Wisteria frutescens and Wisteria sinensis, Amphicarpaea bracteata, Desmodium rotundifolium, Strophostyles helvola, as well as the species in the genera Lathyrus, Rubus, and Coronilla. Habitat PreFerence: A. americana can grow in partial or no shade (5). It prefers low and moist woods, thickets, stream and riverbanks, ponds, marshes, meadows, and wet ravines (1, 4). Geographic Distribution in Michigan: Located in 32 counties of the Lower Peninsula, nearly all in the southern half, and in Mackinac, Delta, and Menominee counties of the Upper Peninsula (1). Known Elevational Distribution: Groundnut can be found cultivated up to elevations of 1000m (16). Complete Geographic Distribution: Native to the eastern United and Canada. A. americana is found in every state east of and including Colorado, and in Quebec and Ontario in Canada (14). -

Apios Americana. the GROUND NUT Is a Herbaceous Climbing Plant, Reaching About 4Ft Tall

Alternative Root Crops Although this leaflet is titled Alternative Root Crops, I am not going to stick strictly to the botanists definition of a root, but am instead being much more lax and will be discussing all types of underground storage organs including tubers, bulbs and corms. The traditional root crops grown in Britain are potatoes, parsnips, carrots, beetroot, onions, turnips and swede with lesser known plants such as Jerusalem artichokes, celeriac, Chinese artichokes, radishes and winter radishes (mooli) playing a minor role. Of these, potatoes are by far the most important. They are very high yielding and, because they have a mild flavour that goes well with many other foods, they are widely used as a staple crop. They do have many disadvantages though, especially in their high susceptibility to disease and in particular to blight (for which there is no acceptable organic treatment as yet). Most of these traditional crops have been selectively bred, sometimes over thousands of years, for improved flavour and yields. Potatoes, for example, were extremely low-yielding when first introduced from S. America. The wild carrot has a thin woody root that bears little comparison to the cultivated plant. This selective breeding, however, has not been an unconditional success. Potatoes must be one of our most disease-prone crops - you only have to look at them and they go down with blight. Carrots suffer from root fly and violet root rot, assuming you can get them past the seedling stage without them being eaten by slugs or overtaken by weeds. Many of the plants mentioned in this leaflet, on the other hand, have never been bred as a food crop so yields will often be rather lower. -

Determination of Genistein and Protein Content in Apios Carnea and Apios Fortunei from China, and Apios Americana

Modern Applied Science; Vol. 9, No. 1; 2015 ISSN 1913-1844 E-ISSN 1913-1852 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Determination of Genistein and Protein Content in Apios Carnea and Apios Fortunei from China, and Apios Americana Kenneth Brown1, Jianhua Li2, Katherine Wirth1, Emily Wilkins1, Jim Tufts1 & Fernando Bahena1 1 Department of Chemistry, Hope College, Holland, Michigan, USA 2 Department of Biology, Hope College, Holland, Michigan, USA Correspondence: Kenneth Brown, Hope College, Department of Chemistry, 35 East 12th Street, Holland, Michigan 49423, USA. Tel: 1-616-395-7173. E-mail: [email protected] Received: July 30, 2014 Accepted: August 14, 2014 Online Published: December 2, 2014 doi:10.5539/mas.v9n1p103 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/mas.v9n1p103 The research was financed through the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the National Science Foundation (CHE-REU Grant 1141786). Abstract Several different groundnut Apios species obtained from various locations in China and North America were evaluated for genistein and total protein content. This preliminary research was conducted to determine the viability of these species as potential food sources. High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was the instrumentation used to determine the concentration genistein in Apios (Fabaceae) species including A. carnea and A. fortunei from China and A. americana from North America. The extracts of 80% ethanol were analyzed under HPLC isocratic conditions at a wavelength of 270 nm and the Lowry Protein Assay at 650 nm was utilized to determine the amount of protein in the samples. A linear calibration range of 0 ppm-340 ppm for genistein was obtained and the presence of genistein was also confirmed using LC-MS (M+, m/z 271). -

Uses Apios Americana

ECHO Development Notes (EDN) | EDN Issue #151 Apios americana Michelle Boutell Apios americana is a climbing, perennial vine and a member of the legume (Fabaceae) family. Common names for this crop include apios, ground nut, wild bean, bog potato, wild potato, Virginia potato, Indian potato, and wild bean. The plant, native to eastern parts of North America, was widely cultivated by Native Americans for its edible tubers and beans. It has grown well in the subtropical climate of ECHO’s Global Farm in southwest Florida (Sobetski, 2021). Its preference for trellis support makes it more difficult to grow on a field scale than a root crop like cassava (Manihot esculenta); however, A. americana is well-suited for small plantings around the home, producing protein-rich tubers that can be cooked in multiple ways. Figure 8. Apios americana tubers. Source: Holly Sobetski Uses Many legumes are grown as green manure/cover crops, but A. americana is primarily cultivated for its starchy tubers that are an excellent source of carbohydrates and protein (Figure 8; Table 2). A. americana roots have more protein than other root crops shown in Table 2, and the protein in A. americana roots contains all the amino acids essential to human health (Neacsu et al., 2021). 1 / 5 Table 2. Protein and carbohydrate content of Apios americana and three other major root crops. Units of measure are grams (g) per 100 g of dry matter. Cassava Sweet Nutritional Apios (Manihot Potato(Solanum Potato(Ipomoea category americanaZ esculenta)Y tuberosum)Y batatas)Y Protein 13-17 3 9 5 Carbohydrate 47 87 67 78 ZData from Kalberer et al. -

Edible Wild Plants Native to the Northeast U.S. and Eastern Canada

Edible Wild Plants Native to the Monday, March 12, 2018 Northeast U.S. and Eastern Canada 10:02:10 PM Compiled and Copyrighted © by Russ Cohen, [email protected] http://users.rcn.com/eatwild/bio.htm Common Name Botanical Name Native Type of plant Preferred habitat Comments to MA? Box Elder Acer negundo Yes small to medium tree wetlands and other damp areas; a species of Maple; sap may be tapped floodplains + boiled down for syrup Maple, Red Acer rubrum Yes medium to large tree red maple swamps (of course) can be tapped for sap like Sugar Maple Maple, Silver Acer saccharinum Yes medium to large tree forested floodplains and other wet can be tapped for sap like Sugar ground Maple; seeds are edible raw Maple, Sugar Acer saccharum Yes medium to large tree hardwood forests; roadsides sap is source of maple syrup and sugar Sweet Flag (Calamus) Acorus americanus Yes herbaceous perennial wet fields and meadows; sunny the similarly-appearing A. calamus is wetlands; along waterways apparently non-native to MA Wild Leek (Ramps) Allium tricoccum Yes herbaceous perennial rich, mesic woods, such as those over-collecting by commercial diggers pref. by maidenhair fern + is harming ramps + habitat - pick 1 Dutchman's breeches leaf/plant only Juneberry/Shadbush Amelanchier spp. Yes Shrub/small tree likes to grow near water, but often fruit ripe in late June; flavor is a cross planted in parks and other between cherries and almonds landscaped areas Hog Peanut Amphicarpaea Yes herbaceous perennial vine damp spots in woods w/ some sun; small subterranean seeds -

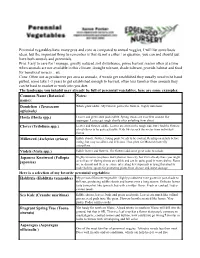

Perennial Vegetables Have Many Pros and Cons As Compared to Annual

Perennial vegetables have many pros and cons as compared to annual veggies, I will list some basic ideas, but the important thing to remember is that its not a either / or question, you can and should just have both annuals and perennials. Pros: Easy to care for / manage, greatly reduced soil disturbance, prime harvest season often at a time when annuals are not available in this climate, drought tolerant, shade tolerant, provide habitat and food for beneficial insects... etc. Cons: Often not as productive per area as annuals, if weeds get established they usually need to be hand pulled, some take 1-3 years to get established enough to harvest, often less familiar then annuals they can be hard to market or work into you diet. The landscape you inhabit may already be full of perennial vegetables, here are some examples: Common Name (Botanical Notes: name): Dandelion (Taraxacum Whole plant edible. My favorite part is the flowers. Highly nutritious. officinale) Hosta (Hosta spp.) Leaves and green seed pods edible. Spring shoots are excellent cooked like asparagus. Leaves get tough shortly after unfurling from shoot. Clover (Trifolium spp.) Leaves and flowers edible. Leaves are a bit on the tough side, but i find the flowers of red clover to be quite palatable. Kids like to suck the nectar from individual florets. Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) Edible shoots, flowers, young pods. Needs to be cooked. Read up on details before eating, but easy to collect and delicious. Host plant for Monarch butterfly caterpillars. Violets (Viola spp.) Edible leaves and flowers. The flowers add some great color to salads. -

A Natural History Study of the Vascular Flora of Cedar Bog, Champaign County, Ohio12

THE OHIO JOURNAL OF SCIENCE Vol. 74 MARCH, 1974 No. 2 A NATURAL HISTORY STUDY OF THE VASCULAR FLORA OF CEDAR BOG, CHAMPAIGN COUNTY, OHIO12 CLARA MAY FREDERICK Division of Science-Mathematics, Urbana College, Urbana, Ohio 43078 ABSTRACT Cedar Bog Nature Preserve is a relict boreal bog situated in the Mad River valley in Champaign County, west-central Ohio. Originating following the retreat of the Wis- consin glacier, it has been maintained by the combination of a usually cool moist micro- climate and a uniform flow of cool ground water. Microclimatic data recorded from 1963 through 1969 demonstrate that Cedar Bog has cooler temperatures and a shorter frost- free period than do adjoining areas. These two factors have resulted in the survival of plants unique to this part of Ohio. Within the Bog area, six major plant associations have been identified—the bog meadow, marl meadow, arbor vitae, swamp forest, hardwood forest, and shrub associa- tions. The marl meadow (the wettest area) lies in the northeast section, with the bog meadow and arbor vitae associations south of it, the swamp forest occurring adjacent to the arbor vitae, on the west and the hardwood forest lying beyond the swamp forest. A total of 546 taxa of vascular plants was identified in the Bog; this list is presented, to- gether with information on occurrence, abundance, and whether or not the species has been reported earlier. Of these taxa, 173 were previously unreported for Cedar Bog, whereas 21 with earlier documented occurrences are now apparently extinct in the Bog. INTRODUCTION Cedar Bog Nature Preserve, under the supervision of the Ohio Historical Society, is located in sections 31 and 32, Urbana Township, Champaign County, Ohio, on the Saint Paris topographic quadrangle (fig. -

Native Plants

ARLINGTON COUNTY NATIVE PLANT LIST (Version 9-1-20) The following list of vascular plants are considered native to Arlington County as initially determined through extensive flora inventories conducted from 2005-2009. This document can be considered to be accurate, but not complete. This listing will be updated periodically, identified by (Version Date), as additional species are identified. As work progresses on producing a definitive native flora list, a secondary source for checking the nativity status of a questioned species is the Digital Flora Atlas of Virginia – found at http://vaplantatlas.org/ . It is important to note that some species are periodically reclassified by the scientific community and may experience a change in genus name or family classification. Responsibility for updates and list maintenance resides with the Natural Resource Manager within the Department of Parks, Recreation and Cultural Resources (PRCR). PTERIDOPHYTA FERNS & FERN ALLIES Aspleniaceae Spleenwort Family Asplenium platyneuron Ebony Spleenwort Dennstaedtiaceae Bracken Fern Family Dennstaedtia punctilobula Hay-scented Fern Pteridium aquilinum Bracken Fern Dryopteridaceae Wood Fern Family Athyrium asplenioides Lady Fern Cystopteris protrusa Lowland Brittle Fern Deparia acrostichoides Silvery Glade Fern Dryopteris carthusiana Spinulose Wood Fern Dryopteris intermedia Evergreen Wood Fern Dryopteris marginalis Marginal Wood Fern Homalosorus pycnocarpos Matteuccia struthiopteris Ostrich Fern Onoclea sensibilis Sensitive Fern Polystichum acrostichoides Christmas